re inflation / money dilution, etc etc

bloomberg.com

Commodity Futures as Inflation Hedge Have Their Moment

With inflation likely to stay elevated, preserving wealth becomes as important as maxing returns. And stocks may not be the best hedge. Meanwhile, the US housing market remains robust.

John Authers

28 February 2023 at 13:22 GMT+8

Looking for inflation hedges.

Photographer: Christopher Dilts/BloombergTo get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

Hedge Me Not

Not everyone invests in financial assets with the sole purpose of maximizing profits. With inflation surging to 40-year highs, preserving wealth seems at least as important. How to do that best is anyone’s million-dollar guess. Rather than look to bet on which security will reap the most generous gains, what traders want is a safe hedge that will minimize the risk that inflation eats away their wealth.

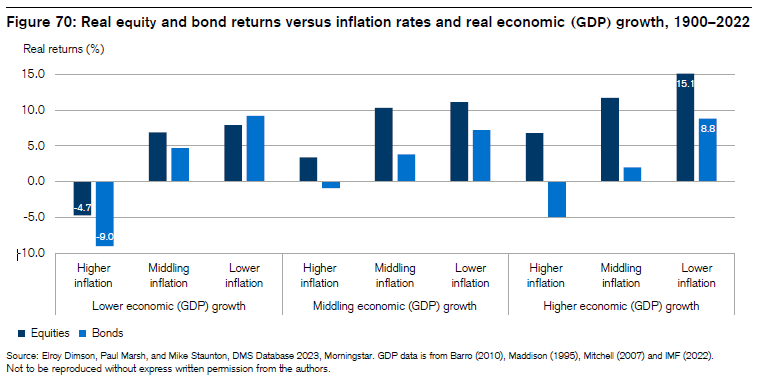

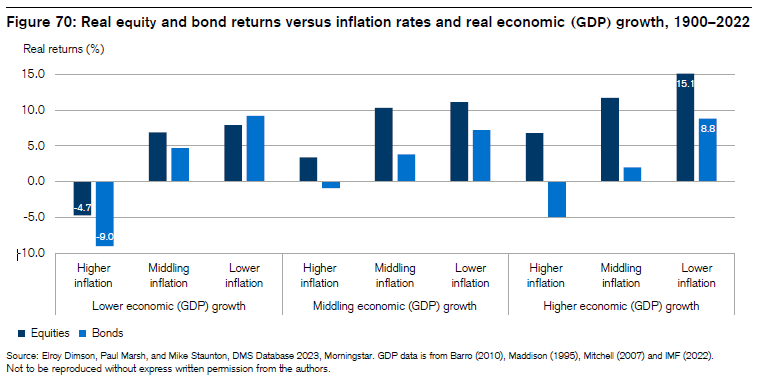

That hedge has long been perceived to be equities. But according to the Credit Suisse Global Investment Returns Yearbook 2023, stocks don’t in fact provide protection against inflation. And if the past 123 years of data is any guide, inflation has negatively impacted both bonds and shares. Equities have been hurt less, but that’s not the same as providing a true hedge.

Just look at 2022: both asset classes fell amid aggressive monetary policy tightening, catapulting the traditional 60/40 portfolio to possibly its worst year ever. The stock-bond correlation had been mostly negative for over two decades ending in 2021, making them a hedge for each other, the authors wrote. To be sure, returns on both have historically been much lower amid hiking cycles than easing ones, they said. But both fare worse as inflation rises over time. The following numbers cover a range of countries for the 123 years starting in 1900:

Now in its 15th year under the sponsorship of the Credit Suisse Research Institute in collaboration with London Business School, the yearbook covers all the main asset categories in 35 countries. Since its founding, it has been authored by financial historians Elroy Dimson, a professor at Cambridge University, and Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of the London Business School. Each edition can be treated as an update to their seminal work, Triumph of the Optimists, a massive empirical study that pieced together 101 years of returns for stock and bond markets.

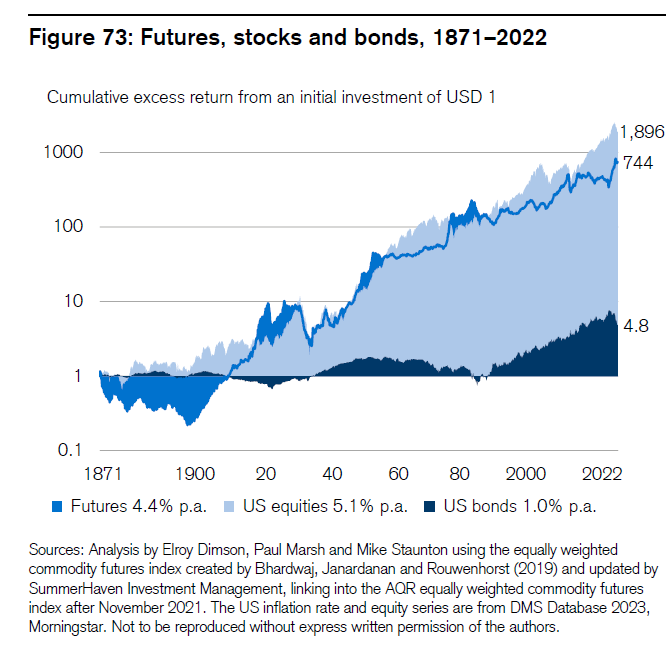

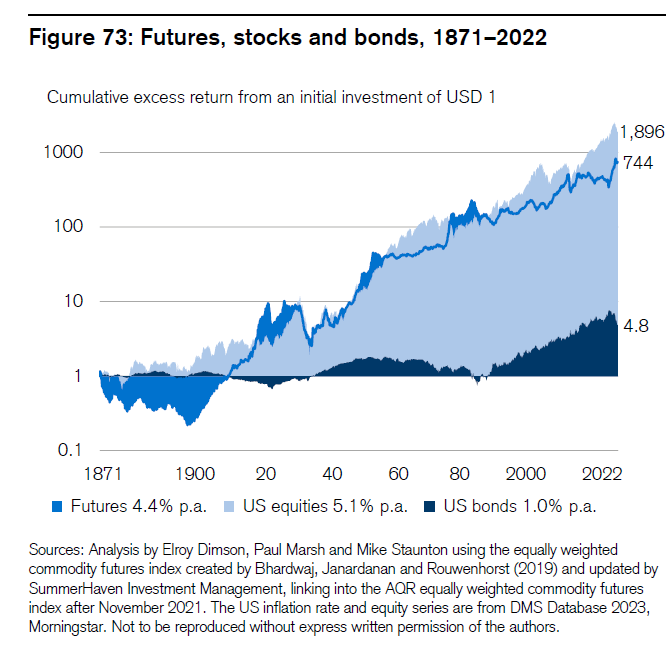

This huge span has seen many episodes of inflation. Where could investors hide? Dimson, Marsh and Staunton suggest you should consider commodity futures. They back that with data on returns going back to 1871.

If it seems contrarian to prevailing beliefs, worry not. Surging commodity prices, particularly those that are energy-related, were major factors in the steep rise in inflation in 2021 and 2022 and then pegged back sharply. But commodity futures — pooled together as an asset class — do serve as an effective “diversifier” in portfolios.

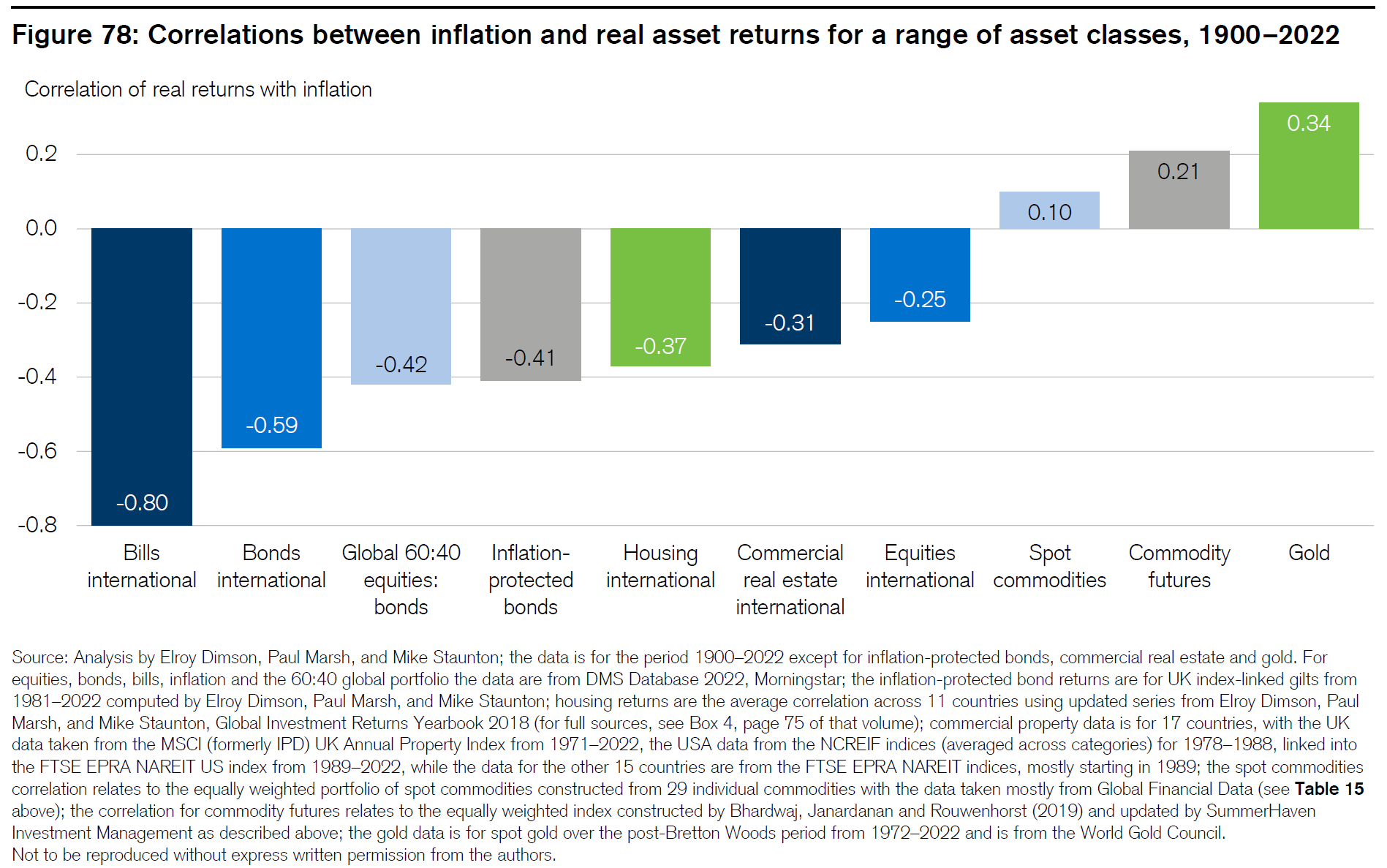

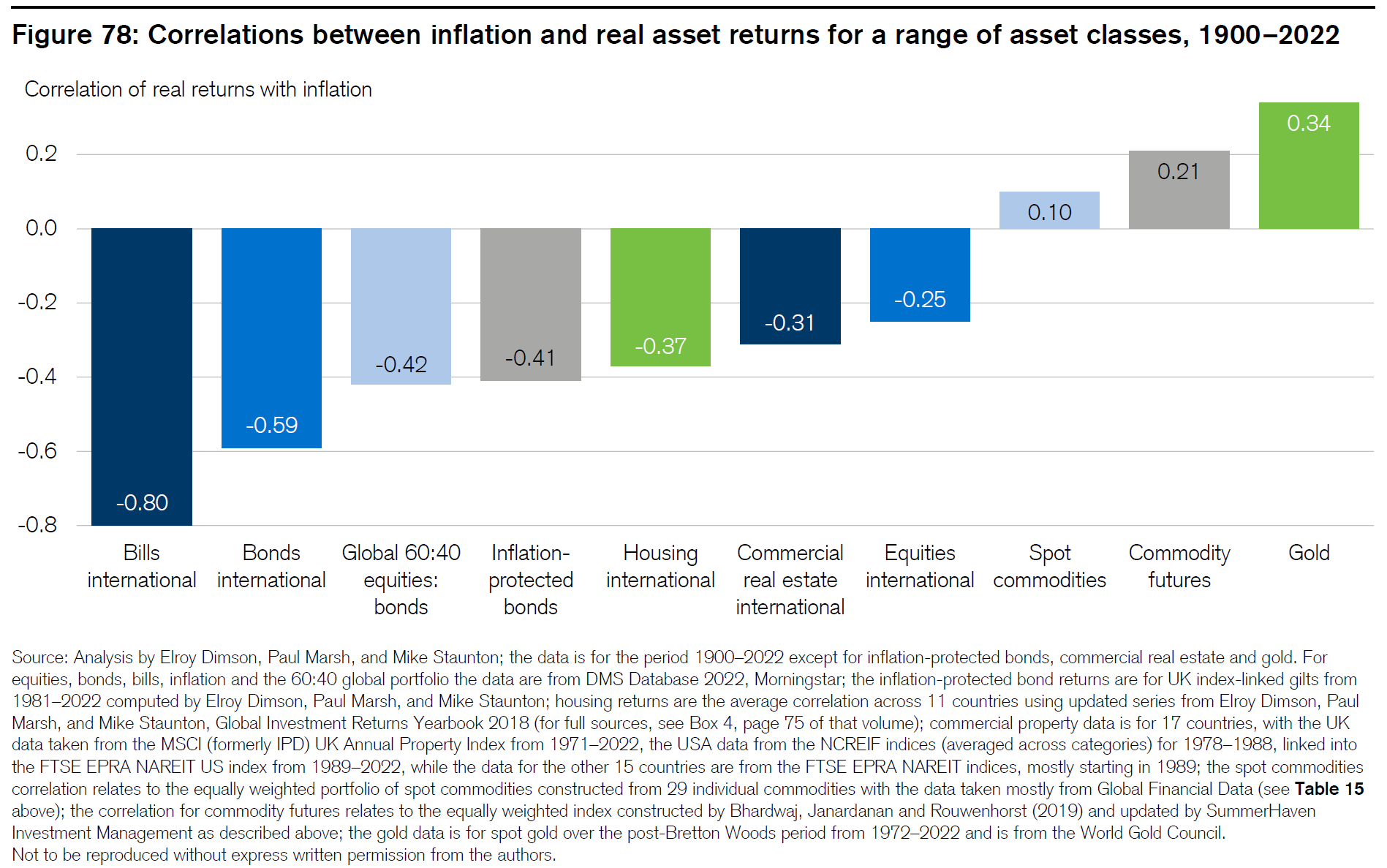

Why? Because they are “negatively correlated with bonds, lowly correlated with equities and also statistically a hedge against inflation itself,” the authors wrote. Bonds, equities and real estate tend to be negatively correlated with inflation. Over the 152 years they examined, only commodities had a positive correlation, making them the only true hedge:

These numbers seem irrefutable. If you’re worried about inflation, you should hold some commodities. And indeed, the sector is diverse enough that it also enables hedges against different types of inflation. Citing research from Investing Amid Low Expected Returns by Antti Ilmanen of AQR Capital Management, they point out:

Commodity futures portfolios provide the instruments needed to hedge against different types of inflation. Energy futures perform well during energy-driven cost-push inflation; industrial metals during demand-pull inflation; and precious metals, especially gold, perform well when central bank credibility is questioned.

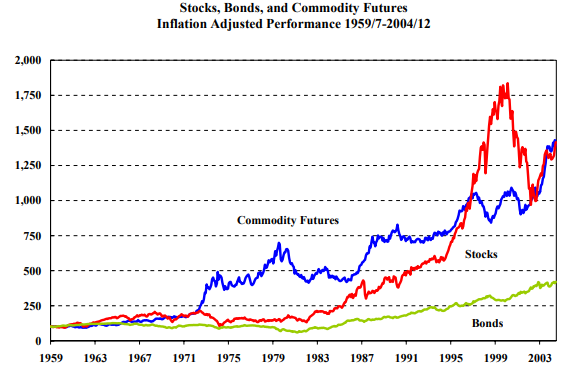

Beyond all of this, commodities futures’ long-term returns have been healthy, even if equities have performed considerably better:

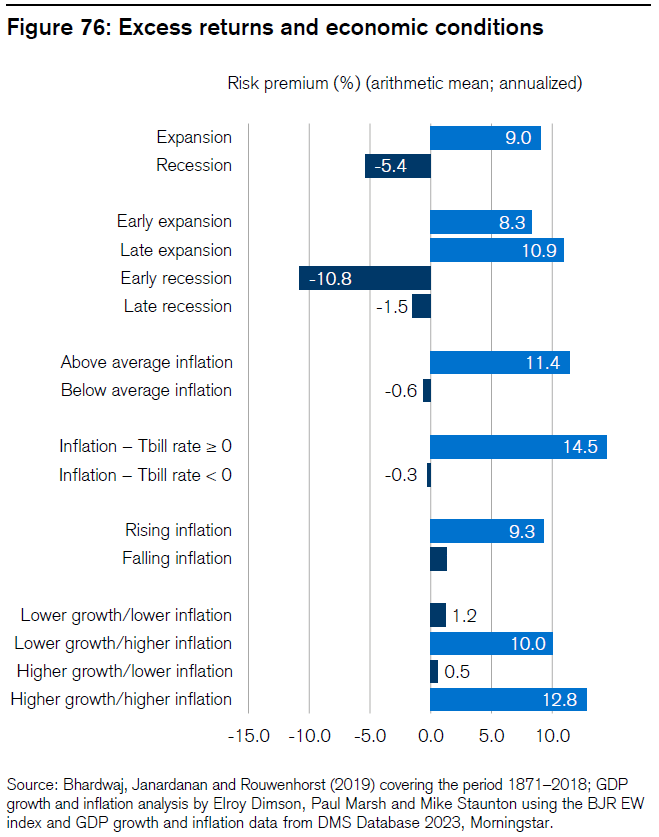

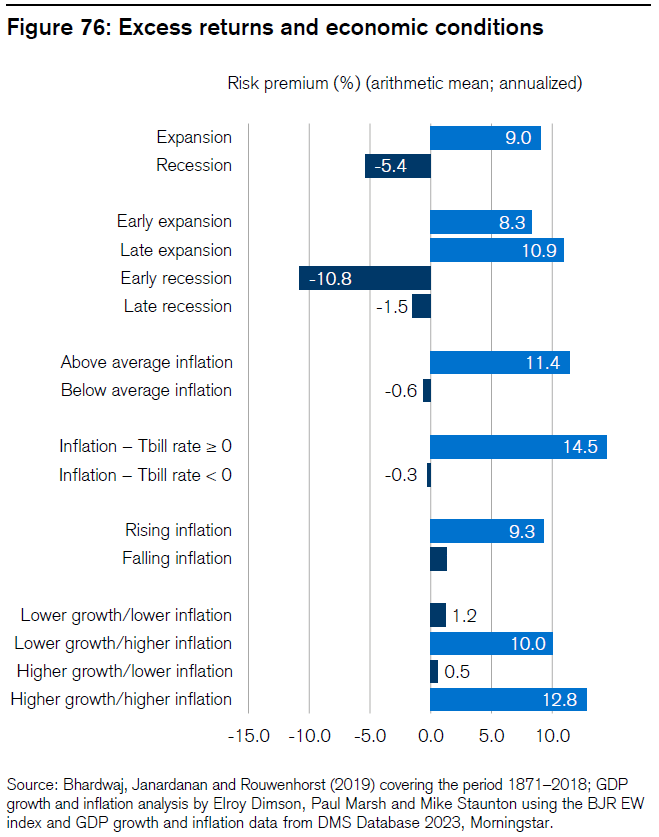

But nothing is simple. Commodities are, like stocks, often susceptible to deep and lengthy drawdowns. And because they are correlated with inflation, they have a penchant to underperform in periods of disinflation. The following massive number-crunching shows the excess returns you can expect from a basket of commodities in different situations for the US economy. The bottom line is while they’re a great hedge against inflation, they are absolutely not a hedge against recession:

Anyone trying to time the market will have great difficulties. Conditions of rising inflation are best and early recession periods are worst, and as the latter tend to come immediately after the former, it would be easy to be caught out. But the bottom line is that provided you stay in a diversified commodity basket for the long term, you can expect to do much better than cash:

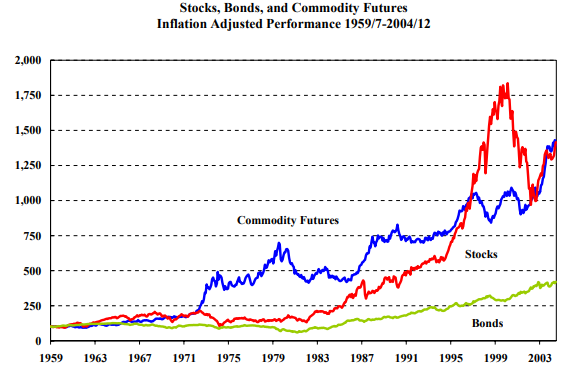

An equally-weighted portfolio of those same futures contracts gave an annualized excess return over Treasury bills of more than 3%, again showing the power of diversification. And then we come to the greatest problem, which is the size of the futures market. It’s quite small, which means that if everyone buys into commodity futures at once, there would be every risk of a bubble and a subsequent burst. Increased interest from investors in futures was widely blamed for the commodity price spike that directly preceded the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. Another very famous work of academic research first published in June 2004, Facts and Fantasies About Commodity Futures by the Yale School of Management academics Gary Gorton and Geert Rouwenhorst, found that futures acted as an almost perfect diversifier, reducing the risk of a portfolio of stocks and bonds without denting returns. This was perhaps their key conclusion:

In addition to offering high returns, the historical risk of an investment in commodity futures has been relatively low — especially if evaluated in terms of its contribution to a portfolio of stocks and bonds. A diversified investment in commodity futures has slightly lower risk than stocks — as measured by standard deviation. And because the distribution of commodity returns is positively skewed relative to equity returns, commodity futures have less downside risk. This suggested that commodity futures were something very close to a “free lunch.” When Facts and Fantasies was published, this was how they compared to long-run stock and bond returns; the chart is taken from the research paper:

What was not to like? As might be expected, the paper was followed by quite an influx, much of it from asset managers who had not previously dabbled in commodity futures. Thanks in part to the launch of a number of exchange-traded funds tracking commodity indexes, the number of futures contracts outstanding nearly doubled between 2004 and 2007. In combination with the bull market created by China’s opening after joining the World Trade Organization, this drove quite a spike in returns. A bust followed. It’s a safe bet that a lot of the people who dove in aren’t terribly happy about how it worked out. This is how Bloomberg’s broad commodity futures index has performed, on a total return basis, since the article’s publication in June 2004:

This looks awful and explains why commodity futures are thoroughly out of fashion again. It’s possible that the influx into the asset, often referred to as its “financialization,” amplified the boom and subsequent bust. But does history since 2004 invalidate Gorton and Rouwenhorst’s research? The Yale academics have published research on this — in Facts and Fantasies About Commodity Futures Ten Years Later they came to the conclusion that it still held good. The correlations among commodities, and commodities’ correlations with other assets “experienced a temporary increase during the financial crisis,” but that this was “in line with historical experience.” Correlations tend to become extreme during periods of forced selling when everyone has to dump everything at the same time. You can find my commentary on this from back in 2015, written for my former employers, here.

The fact that correlations suddenly rose meant that commodity futures had failed to provide a hedge, or insurance, at the time when investors had most needed it. But they argue that the commodity implosion of 2008 was more attributable to the crisis than to financialization. Dimson, Marsh and Staunton seem comfortable with this conclusion, and also point out that global economic conditions over the last decade or so could only be expected to be bad news for materials prices:

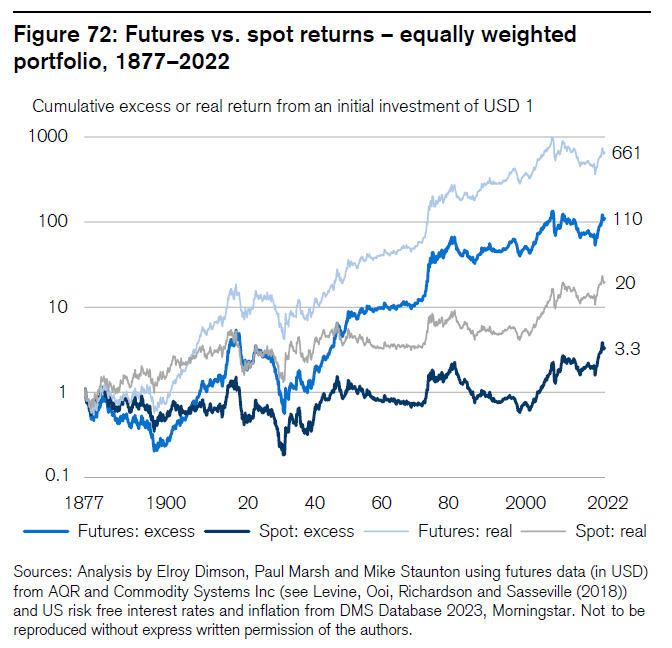

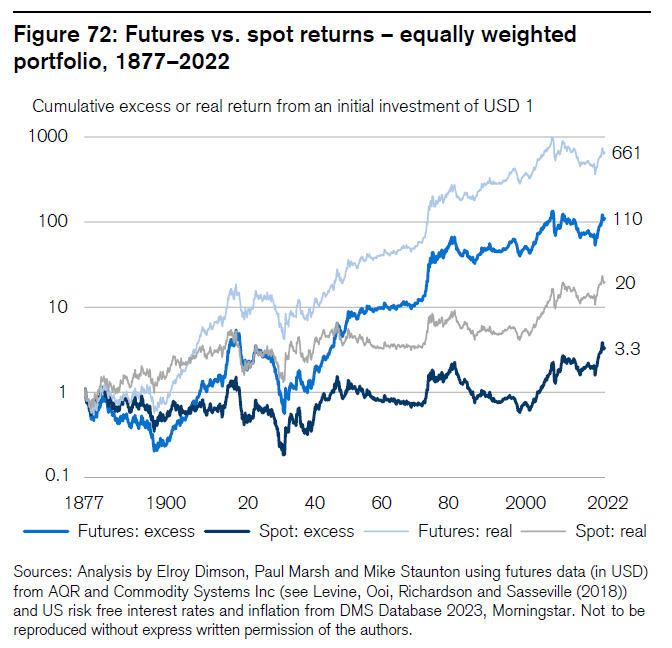

It would seem quite wrong to conclude that the risk premium from futures had disappeared simply because of the Global Financial Crisis drawdown in commodity futures that followed the publication of Gorton and Rouwenhorst’s research. This was a disinflationary and low inflation period, and these are challenging conditions for commodity futures. Why futures and not investing in individual commodities on the spot market? The simple answer is returns. Spot commodities yield very low long returns based on data since 1900, with an average annualized loss of 0.5%. In fact, 72% of the commodities they analyzed failed to beat inflation. However, an equally-weighted portfolio of the same spot commodities offered a much higher annualized return of 2%. Futures perform better, and also enjoy a big benefit from diversification:

Returns aside, purchasing physical commodities is cumbersome. Investors tend to avoid it because they have to deal with the logistical and insurance costs (think oil, cotton, corn or livestock and in the millions of dollars). To learn more about the people who make a very good living from this, read The World on Sale, by Bloomberg colleagues Javier Blas and Jack Farchy, on the shadowy world of the big commodity traders. Simply put, futures are more convenient and cheaper.

Where does this all leave us? Commodity futures don’t offer the totally free lunch many believed before the 2008 implosion. They do, however, offer a uniquely good hedge against inflation. The last decade has shown bad things can happen to returns when inflation is low — but if you’re concerned that inflation will not go without a fight, the case for commodity futures in a portfolio looks very strong.

— Reporting by Isabelle Lee

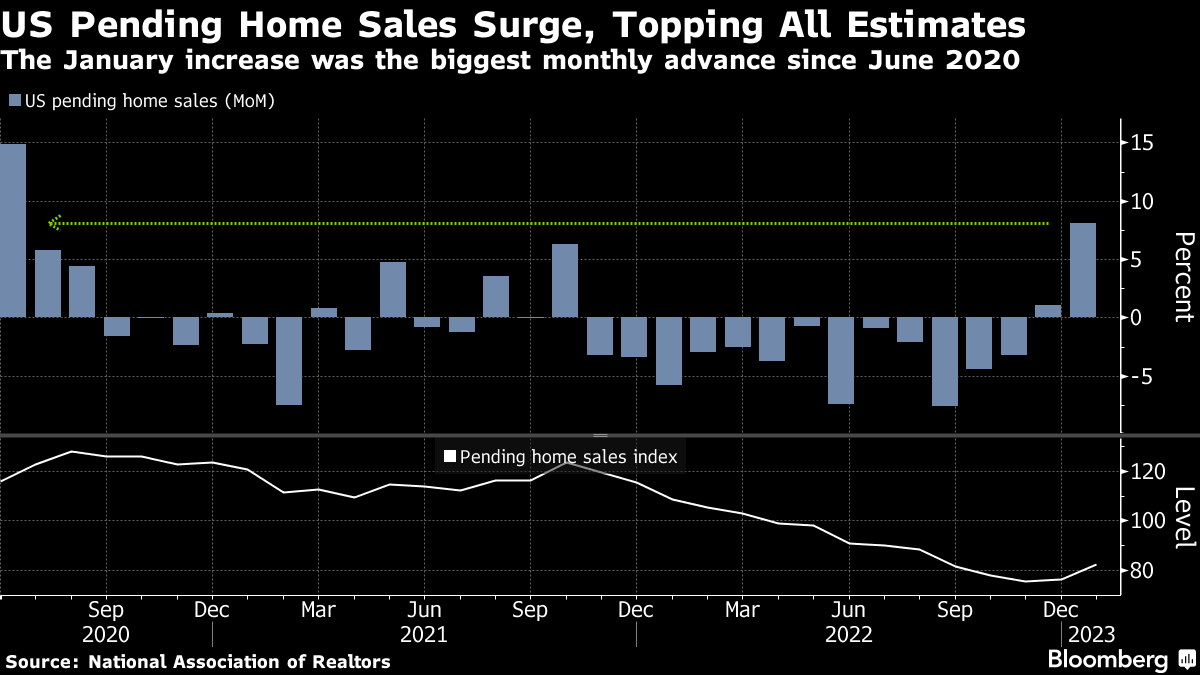

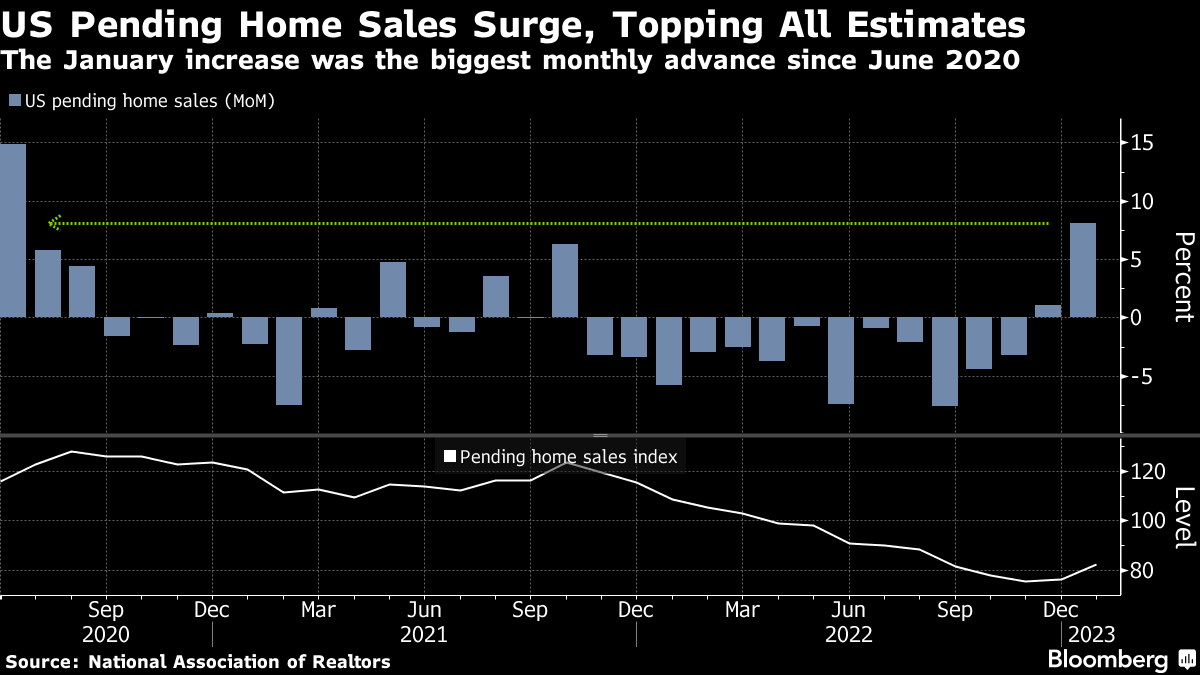

The American Dream Continues

For all the reasons why this shouldn’t be happening anymore — whether it’s demand cooling or supply tightening or the fact that mortgage rates have risen — people are still buying homes. The index of contract signings to purchase previously owned homes, produced by the National Association of Realtors, increased 8.1%, far faster than the 1% forecast, beating all estimates in a Bloomberg survey of economists, and climbing the most since June 2020:

Despite the hike in rates engineered by the Federal Reserve, mortgage rates have eased somewhat in the past few months, helped by the increasing demand from potential buyers. The Fed doesn’t care as much about Wall Street as Wall Street thinks, meaning that market-based indexes of financial conditions including stocks and bonds aren’t so important to them. But they very much care about the rates they control, which are intended directly to take some heat out of housing. It’s fair to surmise that the housing data will help to confirm to central bankers that the easing in financial conditions that has showed up in indexes based on a range of financial markets was seriously premature. Therefore, the situation probably requires more rate hikes:

For Lawrence Yun, NAR’s chief economist, home sales activity seems to be bottoming in the first quarter. He also noted that all four regions of the US saw increases, led by the West (thanks to low home prices), followed by the South, which has been aided by stronger job growth. Buyers, the agency said, simply responded to better affordability from falling mortgage rates in December and January.

The surprising numbers on previously owned homes dovetail with an increase in sales of new US homes in January to the highest level in nearly a year, fueled entirely by purchases in the South.

While this may be a blip, there are broader factors that support this post-pandemic surge. One is the falling price of lumber, which is less than half its record high in 2020. Megan Horneman, chief investment officer at Verdence Capital Advisors, said the elevated cost had been a “massive burden” on homebuilders, pushing house prices even higher. She does note other construction materials like concrete, cement and bricks remain high.

To be clear, the recent downturn in prices isn’t comparable to the 2008 housing bubble. Horneman cited numerous efforts by the government to clean up housing excess by tightening regulations. Instead, she says this “correction” was born out of poor policies during the pandemic:

The rapid rise in inflation and now interest rates has caused the downturn. Unfortunately, housing is cyclical and there is likely still more price correction and negative impact to the economy, especially as consumers may not spend as much as they feel the impact to their net worth. This is necessary and warranted to cool another source of inflation.

For Peter Boockvar, chief investment officer at Bleakley Financial Group, it all boils down to this key question: “How much do prices fall in order to mitigate the sharp rise in mortgage rates at the same time the inventory of existing homes remains historically low?” While the NAR is forecasting just a modest 1.6% drop in prices this year, he said he has seen estimates to the tune of 20%.

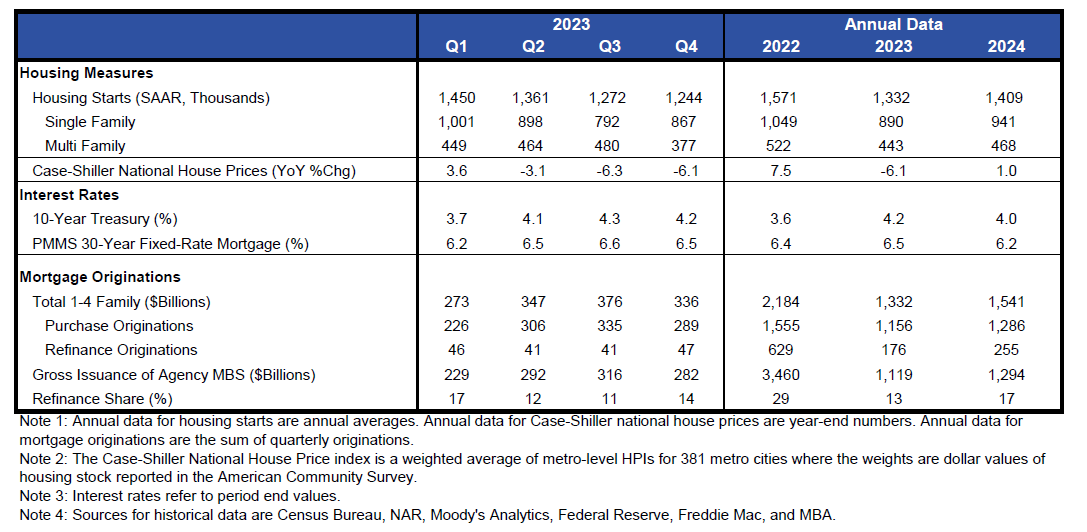

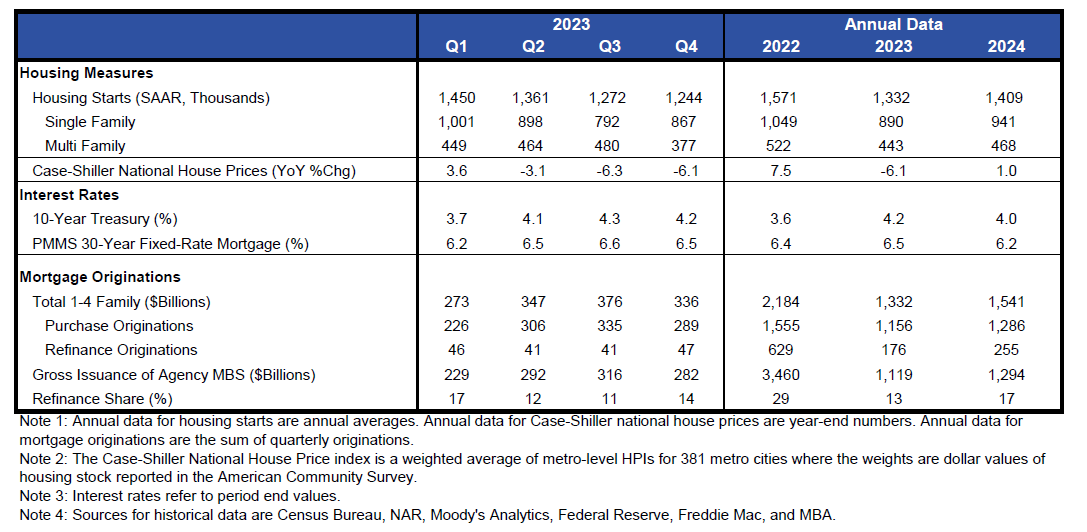

Goldman Sachs Group strategists led by Lotfi Karoui believe affordability will likely continue to pressure demand. This leads to a bottom-up forecast of a 6.1% home-price depreciation in 2023.

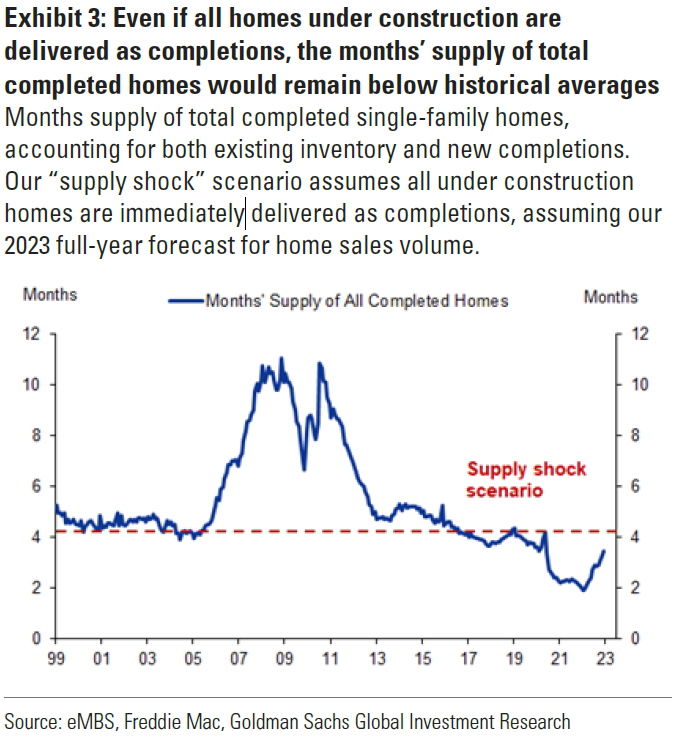

Source: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research

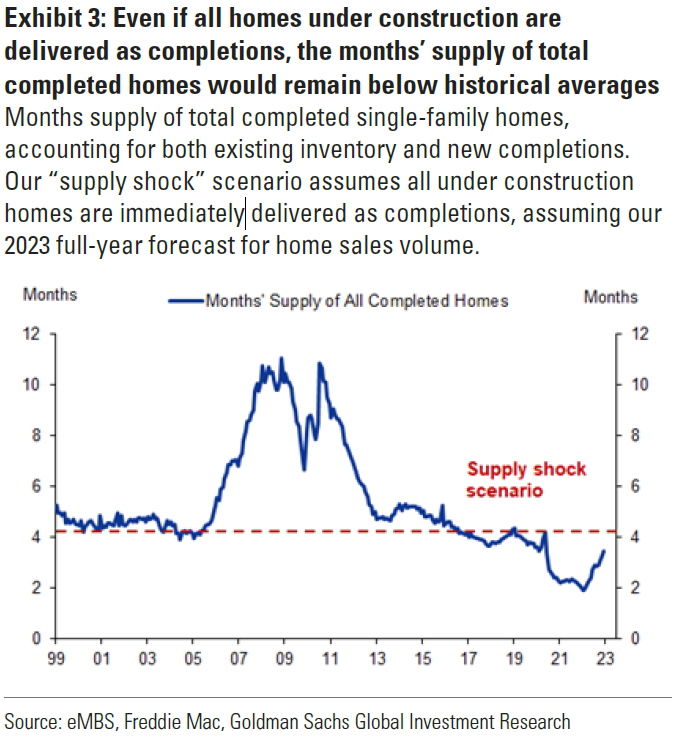

In a Feb. 23 note, they added that the outlook for supply is increasingly more nuanced. While the current pipeline of new homes under construction is historically large, the record-low vacancy rates in existing homes have essentially depleted inventory and tightened supply — which should prop up prices:

On net, this implies a muted impact from completions on the current supply/demand balance of housing and, ultimately, prices. Even if every single home under construction was completed and listed on the market immediately, the months’ supply of homes (the ratio of inventory to annual sales) would still be below historic averages. And on the demand side, the prospect of a gradual recovery of homes sales in the second half of the year should act as an additional buffer.

If the latest data shows anything, it’s that if the housing market is going to slow down or “come in to land,” it will happen later than expected. Much the same can be said of the whole economy.

— Isabelle Lee

Survival Tips

You never know when sport is going to be fantastic. Give it your attention. I’ve been writing this while watching for snow outside the window, and listening to commentary of the cricket match between England and New Zealand in Wellington. The cricket wasn’t particularly spectacular, but it produced hours of delicious tension and ended with the Kiwis winning by a margin of exactly one run. For the many who haven’t a clue whether this is anything to write home about, this was only the second international test match to be settled by such a margin. There’ve also been two ties. That’s out of a total 2,494 matches since the first international contest between England and Australia in 1877. Totaling the two teams’ scores for the whole game, New Zealand won 692-691. As New Zealand are great sports, and England have a New Zealander as coach and a New Zealand-born captain, it’s very hard to begrudge the result. Or to quote the official England team response: “We can't even feel too gutted about that. What an incredible match. Test cricket as we want to play it and see it. The greatest format of the game is alive and kicking and we'll do everything we can to entertain fans across the world.”

In some other sports, notably basketball, you can expect a lot of scoring and you have a good chance of a tight finish. This is less likely in cricket, which is why some find it boring. But it does leave open the possibility of something extraordinary, even when the last few hours of play didn’t feature any particular spectacular play.

It’s hard to think of equivalents. In English soccer, the league championship has twice in my lifetime been absurdly close: In 1989, Arsenal and Liverpool both finished with 22 wins and 10 draws, and both scored 37 more goals than they conceded. Arsenal won because they scored 8 more goals. In 2012, Manchester City and Manchester United both finished with 89 points, and City won because their goal difference was 8 better over the course of the season. Both were famously decided by goals scored when 90 minutes had already been played in the season’s final game; the goals were both good, but the reason they were famous was the deadlock preceding them.

The only example of a tight finish making otherwise drab play pulsatingly exciting came in snooker, which became a cult in the UK in the 1980s for reasons I can’t struggle to explain. In 1985, the nation watched into the night as Steve Davis and Dennis Taylor, who had each won 17 frames, lock horns in the decisive 35th. The frame lasted 68 minutes, and concluded with about half an hour of each player trying and failing to pot the final black ball. On paper, excruciatingly dull. In practice, a nation was transfixed. Any more examples of absurdly tight sporting encounters out there? And even with the result, I’m so glad I tried listening to the commentary of what appeared to be a dull game on the other side of the world.

More From Bloomberg Opinion:

The Myth of the Inevitable Rise of a Petroyuan: Javier BlasFor Many Homebuyers, It’s New Construction or Nothing: Conor Sen What Was Putin Thinking?: Hal BrandsWant more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter.

— With assistance by Isabelle Lee

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

John Authers at jauthers@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Andreea Papuc at apapuc1@bloomberg.net |