Boeing & Aerospace

Business

With aviation’s future clouded, Airbus looks forward. Boeing holds on

July 20, 2024 at 8:00 am Updated July 20, 2024 at 8:00 am

Boeing isn’t sending any aircraft to the Farnborough Air Show, opening Monday in London. Instead, it’s hunkering down to get production back in shape at home. (Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times)

By

Dominic Gates

Seattle Times aerospace reporter

LONDON, England — At the aviation world’s biggest event of the year, the Farnborough Air Show opening Monday outside London, the contrasting fortunes of Airbus and Boeing will be on stark display.

Airbus will talk about the industrywide supply challenges causing it to delay jet deliveries but also reach forward to describe future airplanes and technologies, including as-yet-unrealized plans for climate-friendly air travel.

Parts shortages have forced the European planemaker to cut its projected jet deliveries this year by nearly 4%. Yet it will capture attention at Farnborough by flying its new long-range single-aisle jet, the A321XLR.

That aircraft seems set to further enhance Airbus’ dominance of the smaller jet sector when it enters service this fall.

In contrast, Boeing, in the throes of a reputation crisis, has dramatically shrunk its participation in the air show.

Boeing said it has reduced its presence at Farnborough to focus on “strengthening safety and quality” and delivering airplanes back at home.

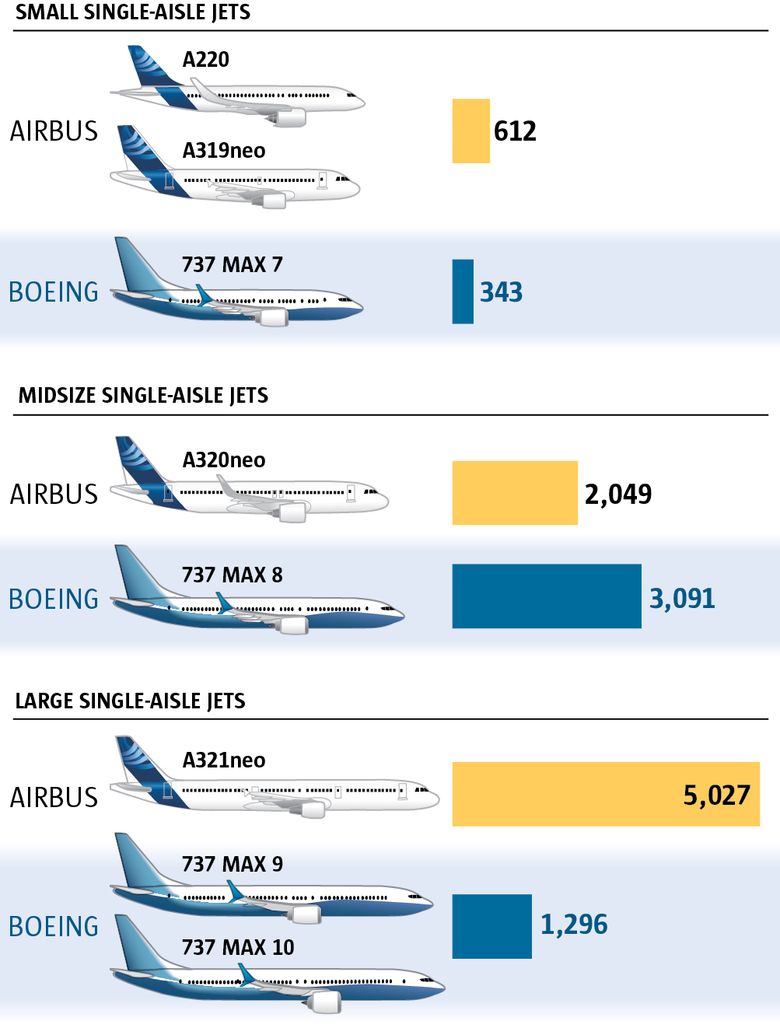

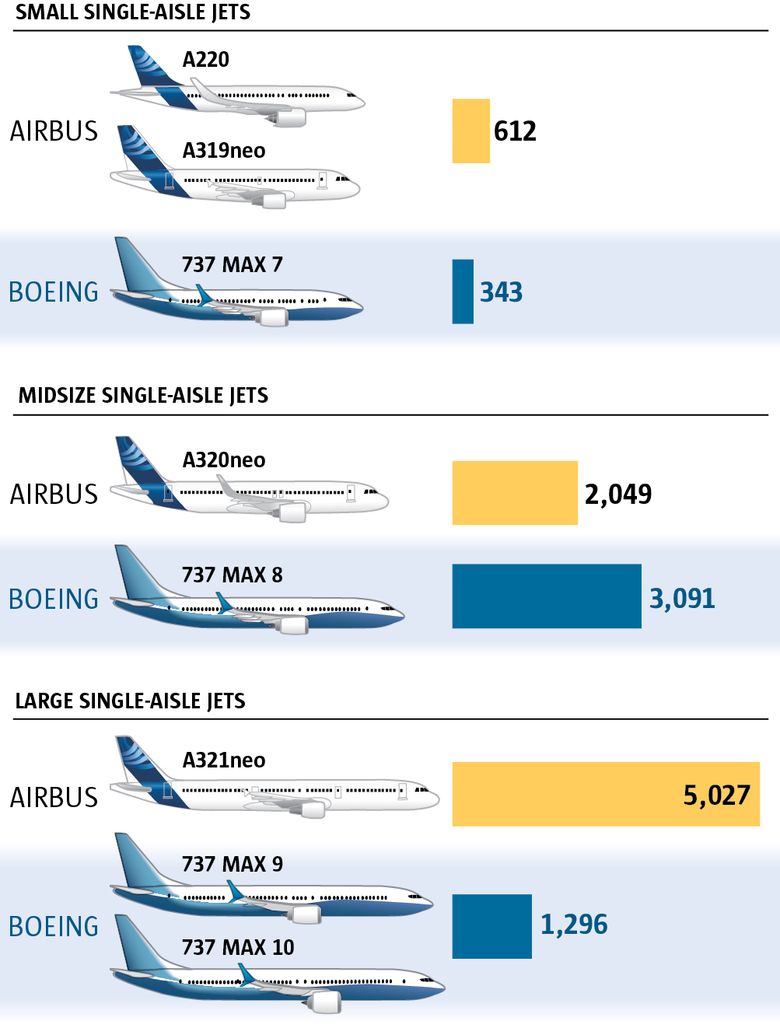

How the Airbus A321neo has run away with the large single-aisle jet market

The single-aisle jet market is reflected in the current order backlogs of Airbus and Boeing. Airbus has an advantage at the smaller end of this sector with its new A220 jet. In the middle, Boeing’s 737 MAX 8 is doing very well against the A320neo. But in the larger single-aisle jet segment, sales of the A321neo easily eclipse those of Boeing’s MAX 9 and MAX 10 models.

Source: Airbus and Boeing figures as of the end of June (Mark Nowlin / The Seattle Times)

It’s not bringing any commercial jets to the air show. New commercial airplanes division boss Stephanie Pope will take press questions on the eve of the show, but otherwise, Boeing is limiting media access.

While Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury gave an advance interview that trade magazine Aviation Week has published before every European air show for 18 years, outgoing Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun pulled out of his interview at the last minute.

That prompted Aviation Week editor-in-chief Joe Anselmo to write a frustrated editorial on “Boeing’s leadership vacuum” and “the company’s decline from an American industrial jewel to a punch line for comedians.”

With nothing to say on future strategy, Boeing hopes to announce some 787 and 777X widebody jet orders to make the show at least a sales success.

Boeing CEO Dave Calhoun, center, arrives for a Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations hearing in Washington, D.C., on June 18. Staggering through five years of... (Graeme Sloan / Bloomberg)

Waiting for clarity from Boeing

Staggering through five years of turmoil since the two deadly 737 MAX crashes and set back again this year when a fuselage hole opened up during an Alaska Airlines flight, Boeing is leaving any description of its longer-term path forward to Calhoun’s yet-to-be-appointed successor as CEO.

Before the new boss comes in to map that future out, the current leadership aims to clear the deck of three major obstacles.

One, the acquisition of the Spirit AeroSystems facilities in Kansas and Oklahoma that make Boeing parts, is now agreed upon. And Boeing has accepted the Department of Justice plea deal related to the 737 MAX crashes. That leaves the Machinists union contract — and a potential strike in September — to be settled.

At a pre-Farnborough press briefing in June, Boeing Senior Vice President Elizabeth Lund focused solely on the current crisis and recapped the efforts to prevent another random quality lapse that could cause an in-flight scare like the Alaska fuselage blowout in January.

“I feel very confident that it will not happen again,” Lund said then.

Andy Cronin, CEO of leading airplane lessor Avolon, said in an interview that based on recent conversations with Pope and her team, he’s been “positively surprised” at her drive to improve the company’s culture.

“They’re doing the right things, and we think they will get there,” Cronin said.

But he said the CEO transition creates pervasive uncertainty.

“We’re keen to see the transition … announced as soon as possible,” Cronin said.

Until a new CEO takes over, Boeing is paralyzed, unable to lay out its future direction even at aviation’s version of a Super Bowl party.

Airbus is looking forward.

Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury, speaks at an earnings news conference in Toulouse, France, in February. In late June, Airbus cut its planned production for the year from 800 to 770 jets, citing delays in the supply... (Matthieu Rondel / Bloomberg)

As post-pandemic demand for air travel continues to soar, and, despite the supply chain challenges, Airbus’ target is still to raise A320 jet family production from 45 aircraft a month now to 75 — though it just pushed that goal out from 2026 to 2027.

Boeing’s rival MAX jet is struggling to get to a rate of 38 aircraft per month by the end of the year; the only announced target beyond that is 50 per month in 2026.

The newly certified A321XLR jet, which should begin service between Boston and Madrid this fall, provides something new to discuss.

It can fly farther than Boeing’s out-of-production 757 and could potentially change the pattern of air travel on transatlantic and other medium-haul routes.

Still, Airbus must also address at Farnborough the major challenge the entire industry faces right now.

That’s a widespread shortage of labor and parts since the COVID-19 pandemic, from jet engines to airliner seats. This has caused constant delays in delivering jets, frustrating airlines that want more planes.

1 of 5 | A 777X flight test aircraft at Boeing’s Everett Delivery Center on June 26. Boeing this month began flying the 777X for certification flight tests. (Jennifer Buchanan / The Seattle Times)

Repairing the broken supply chain

The order books for single-aisle jets are relatively full, though the A321XLR will likely add to them. Otherwise, airlines are expected to ring up significant sales of big widebody jets at Farnborough.

An order from South Korea for more than 20 of Boeing’s new Everett-built 777X is expected. A big Turkish Airlines order for MAXs and 787s may also come through.

The 777X, the world’s largest commercial jet currently built, got a boost on July 13 when the Federal Aviation Administration gave Boeing the green light to begin certification flights on the four 777X test planes based at Boeing Field.

Yet sales are less important this year, as both Airbus and Boeing have orders to keep them busy through most of this decade.

The industry focus is more on how production can meet demand, given labor and parts shortages.

For Boeing, production is very low and can rise only slowly as it must first meet quality standards imposed by the FAA after the blowout on the Alaska Airlines flight.

Boeing 777 freighters and a 777X are under assembly at the widebody jet plant in Everett on June 26. The 777X, the world’s largest commercial jet currently built, got a boost in mid-July when... (Jennifer Buchanan / The Seattle Times)

And Airbus last month cut its forecast delivery for the year from 800 jets to 770, citing shortages of engines, cabin interiors and some airframe parts.

“We have to manage a large number of crises with suppliers, significantly more than what we had before COVID-19,” Airbus CEO Faury told Aviation Week, adding that Airbus is sending “multiple times more people to the plants of our suppliers” to try and fix the cascading problems.

“The production side is more relevant than ever,” said aviation analyst Richard Aboulafia of AeroDynamic Advisory.

With Boeing production rates suppressed and Airbus now delivering so many more jets, he said the European planemaker is positioned to grab more of the scarce supplier capacity.

In a panel discussion at the show, Airbus supply chain chief Delphine Bazaud and her Boeing counterpart Ihssane Mounir will outline their efforts to repair their supplier networks.

The Airbus A321XLR flies at the Berlin Air Show in June. The XLR, which threatens to further secure the dominance of the A320 jet family over Boeing’s 737 MAX, will fly each afternoon at the Farnborough. Air Show. (Courtesy of Airbus)

The star airplane at the show

The A321XLR, which Airbus test pilots will fly every afternoon at the air show, is not just another variant of an already wildly successful airplane. It could open new international routes.

The A321neo, the largest of the Airbus single-aisle jet family has already won a staggering 6,422 orders as of the end of last month, with about 1,400 already delivered to airlines.

This jet’s success rests largely on the lack of Boeing competition to match it. Yes, Boeing has a stretch version of the 737 MAX, the MAX 10, that’s a similar size. But it has a much shorter range and won’t be certified to fly passengers until 2026 at the earliest.

The A321neo is “the biggest and most capable single-aisle jet you could buy,” said Aboulafia. “In the absence of Boeing doing anything even remotely in this segment, it’s very compelling.”

Boeing did consider launching a jet that would have been larger and with greater range, dubbed the “New Midmarket Airplane.” But at the end of 2022, CEO Calhoun definitively dropped that project and announced publicly that there would be no all-new Boeing jet this decade.

With that, airlines realized there was nothing to wait for, no other game in town, and A321neo sales took off. Airbus had sold 425 of them in 2022. The following year, A321neo sales tripled to 1,286 jets.

“The best year for A321neo sales, by a huge margin, was the 12 months after Calhoun said Boeing wouldn’t be doing anything,” Aboulafia said. “He’s the very best CEO that Airbus could ask for.”

Airbus is now doubling down on the A321neo’s success with the A321XLR, featuring a new built-in, additional fuel tank.

The significance of the A321XLR is that it can fly nonstop not just transatlantic but from the interior of the U.S. to airports deep within Europe.

Expensive twin-aisle widebody jets like the Boeing 787 and the Airbus A330 currently ply such routes. Now a low-cost carrier can do it with a single-aisle aircraft that is much cheaper to operate.

And because it’s smaller, it can be used on routes with fewer passengers. While British Airways can fly big jets from London to New York, a low-cost airline could now open a new nonstop route, say Cincinnati to Rome, flying an A321XLR.

Most passengers won’t relish the idea of long flights in a narrowbody airplane with one aisle. Still, cost will count for the passenger as well as the airline. With more than 500 orders placed before it is certified, the XLR is already a success.

“Airbus did some new engineering. It opens new possibilities,” said longtime analyst Adam Pilarski of consulting firm Avitas. “As a flyer, I’m not super happy about it, but, yeah, it may change realities.”

What does this mean for sales of the MAX 10?

It will do fine. Boeing has sold more than 1,000 of them. For airlines that want a bigger jet but don’t need it to fly routes longer than transcontinental, it makes perfect sense.

Alaska Airlines sold off the A321neos it inherited from the 2016 merger with Virgin America and is all in on the MAX 10.

But Alaska is the only airline with that stance. Other airlines that ordered the MAX 10, including American and United, are adding the A321XLR too.

At a pre-air show briefing at Boeing’s Everett widebody jet delivery center in June, Tia Benson-Tolle, senior director of technology and sustainability product development, holds up a container... (Jennifer Buchanan / The Seattle Times)

Flying cars, hydrogen power and sustainability

The big European air shows, Farnborough and Paris in alternate years, have been abuzz in recent years with talk of sustainable aviation and flying cars — electric air taxis that take off and land vertically.

Farnborough should provide a reality check on these futuristic ambitions. Industry observers are looking for results. For sustainable aviation, there’s little to show so far for a lot of investment.

Low-carbon sustainable aviation fuel, touted at multiple air shows as essential to meeting the airline industry’s goal of being carbon neutral by 2050, has been produced in only minuscule quantities.

Sustainable aviation fuel, or SAF, is jet fuel produced from renewable resources. It burns in a jet engine similar to current jet fuel, emitting a similar amount of carbon dioxide. But considering the entire life cycle of the product, the carbon dioxide added to the atmosphere should be minimal.

For the world’s major airlines to achieve their climate protection goals, they need SAF produced affordably and in large quantities.

The airline industry projects that SAF can contribute nearly two-thirds of the reduction needed to meet its sustainability goal.

“SAF is key to getting to net zero,” said Jim Hileman, Boeing vice president and chief engineer for sustainability at a pre-Farnborough briefing last month.

Yet after several years of effort to scale up production through multimillion-dollar investments, Hileman conceded that last year SAF amounted to about 0.1% of all the aviation fuel burned worldwide.

Can that fuel gauge needle rise enough in 2024 to keep aviation’s climate goal within reach?

At the show, both Airbus and California startup ZeroAvia, which has a propulsion research facility in Everett, will describe their development work on a separate decarbonization technology: hydrogen-powered airplanes.

They’ll face more skepticism following the liquidation last month of another startup. Universal Hydrogen, which last year flew a hydrogen-powered aircraft in Moses Lake in Central Washington, burned through $100 million and couldn’t raise more funding.

As for the flying cars, various startups have conducted impressive test flights of prototype air taxis. The technology looks super cool.

In this new aviation niche, one financed by Silicon Valley venture capital and Gulf oil money, leading American air taxi developer Joby is promising commercial service in the U.S. next year while rival Archer has announced a plan to create an air taxi network in the San Francisco Bay Area.

But no air taxis are certified by safety regulators yet. And though Joby and others will have mock-ups of their air taxis on display in an exhibition hall at the show, not one of the many such electric flying machines in development will fly at Farnborough.

Is that future really so close?

The most advanced of the companies developing this technology say they want to focus on completing flight tests and certifying the air taxis rather than taking time to give a flying display at an air show.

Leaders from multiple air taxi startups, including Joby, will be at the air show to provide updates. Their message: The future is coming soon.

That may be true of Boeing too. But for now, the U.S. jetmaker’s future is on hold.

Dominic Gates: 206-464-2963 or dgates@seattletimes.com; Dominic Gates is a Pulitzer Prize-winning aerospace journalist for The Seattle Times.

seattletimes.com |