Boeing & Aerospace

Business

As FAA limit on MAX production lingers, Boeing watchers aren’t worried

March 22, 2025 at 6:00 am Updated March 22, 2025 at 6:00 am

The iconic split wing of the 737 MAX is seen on a plane being assembled on March 9, 2023 in Renton. (Ken Lambert / The Seattle Times)

By

Lauren Rosenblatt

Seattle Times Amazon reporter

Federal safety regulators have capped production of Boeing’s most popular plane, the 737 MAX, for more than a year, following a panel blowout that raised concerns about the manufacturer.

The cap, which holds production at Boeing’s Renton factory to 38 MAX planes a month, doesn’t appear to be loosening any time soon.

Visiting that factory last week, U.S. Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy said the cap is staying in place, even as government officials, Boeing executives and industry analysts say they are seeing the quality and safety improvements they sought after the in-flight blowout on Jan. 5, 2024.

“We have committed to tough love for Boeing,” Duffy said in a video posted to X after his Renton visit. “Once they get their act together, and are producing high-quality aircraft, we’re going to do our job … and give them a little more flexibility. But right now, we’re not there yet.”

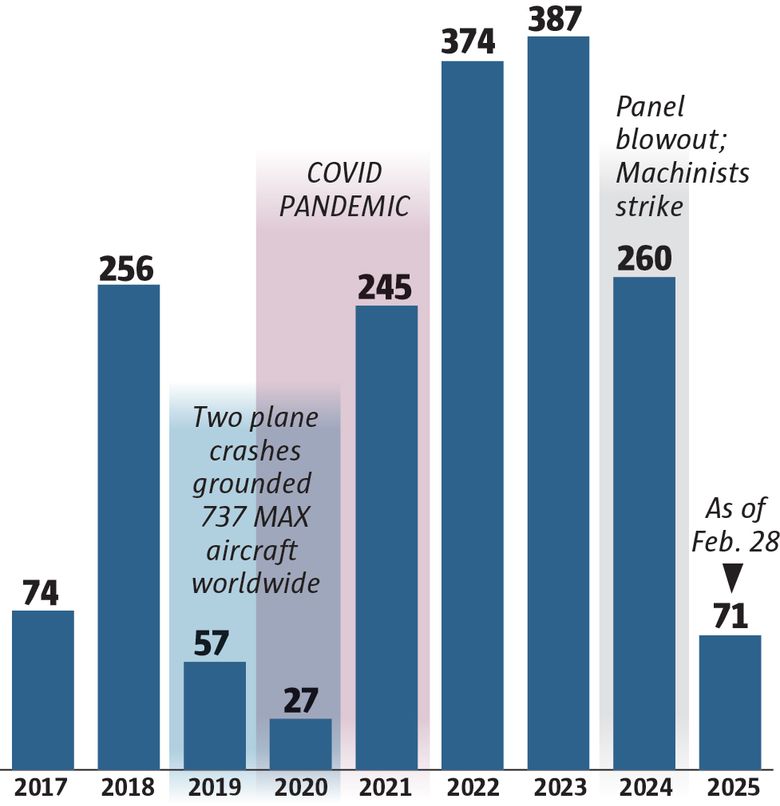

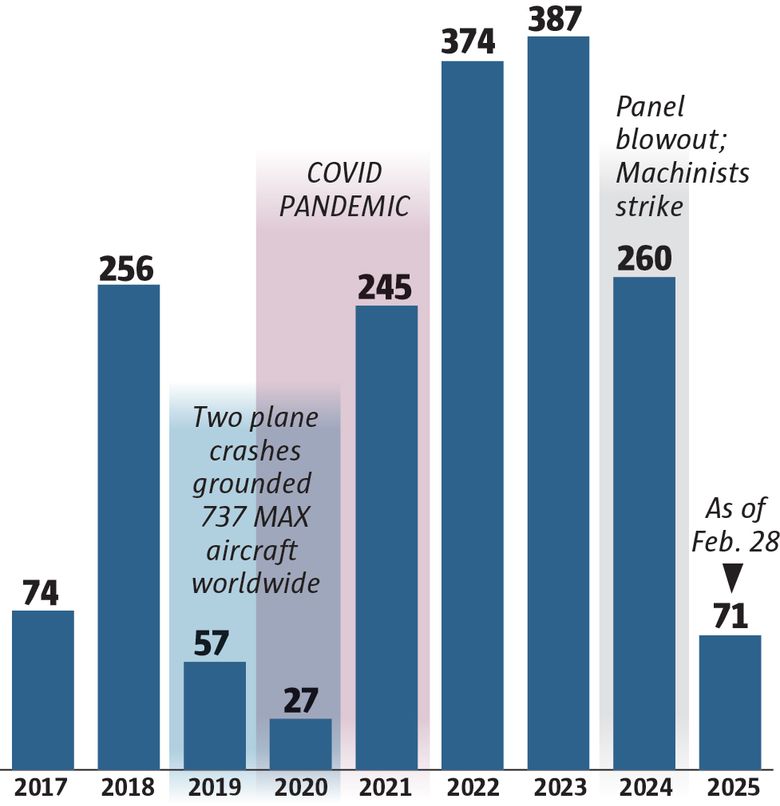

Boeing MAX deliveries over the years

Production of the 737 MAX plane has been marred by crisis since its first delivery in 2017, including two plane crashes, one panel blowout and a Machinists strike in 2024.

Source: Boeing company data (Mark Nowlin / The Seattle Times)

Boeing hasn’t asked regulators to lift the cap and hasn’t yet reached the threshold of producing 38 MAX planes per month, but Chief Financial Officer Brian West has said the company hopes to reach that rate later this year and then seek approval to go higher.

The cap — an unprecedented move by the Federal Aviation Administration, a part of the Department of Transportation — was another setback for the airplane model that has been plagued by crashes, pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions and a Machinists strike.

But industry analysts aren’t worried after a year of stunted production.

All Boeing has to do now is “more of the same,” said Jefferies analyst Sheila Kahyaoglu, who recently visited Boeing’s South Carolina factory where it produces the 787 widebody plane. Though they’re different production lines, Boeing has focused its efforts on improving quality and safety across its factories.

In South Carolina, Kahyaoglu said, Boeing made it easier to find tools and access instructional videos to get questions answered rather than relying on co-workers. The company also implemented new software to track work done on the planes with unique 20-digit codes that include the factory location, work station and task performed.

“Yes, Secretary Duffy made those comments,” Kahyaoglu said. “But we’ve seen significant improvement.”

Boeing launched the 737 MAX — an update to its earlier 737 model with larger engines — in 2011 to compete with rival Airbus’ A320neo jet.

The plane quickly became its most popular and, still today, “there’s no limit in demand,” said Joseph Phillips, a business professor at Seattle University.

Because it is Boeing’s main moneymaker, the FAA’s production cap on the MAX can significantly affect Boeing’s finances.

That’s particularly important this year, as Boeing struggles to rein in expensive defense contracts, recover from a Machinists strike that halted production for two months and dig out from regulatory scrutiny following the panel blowout.

“The cash flow of selling planes is obviously very material to their financial health,” Phillips said. “Not being able to put more planes out the door and ship them to customers just makes it harder to come back.”

After first delivering the plane in 2017, the MAX production lines ground to a halt following two tragic crashes months apart.

In October 2018, a MAX 8 crashed shortly after takeoff in Indonesia, killing 189 people. In March 2019, another MAX 8 crashed in Ethiopia, killing 157 people. Investigators later determined an error in a new software system on the MAX caused both aircraft to nosedive.

The MAX was grounded until November 2020.

As Boeing worked to recover from the grounding, the COVID pandemic disrupted the aerospace supply chain, leading to further production delays.

By 2023, Boeing’s then-CEO Dave Calhoun was optimistic about the MAX’s future, setting a goal to surpass 2019 production levels.

But in January 2024, a panel blew off a MAX 9 shortly after it took off from Portland, reigniting scrutiny of the manufacturer and leading the FAA to cap MAX production at 38 planes per month.

Most Read Business Stories Boeing spent the past year working on a safety and quality plan submitted to the FAA, and steadily increasing production.

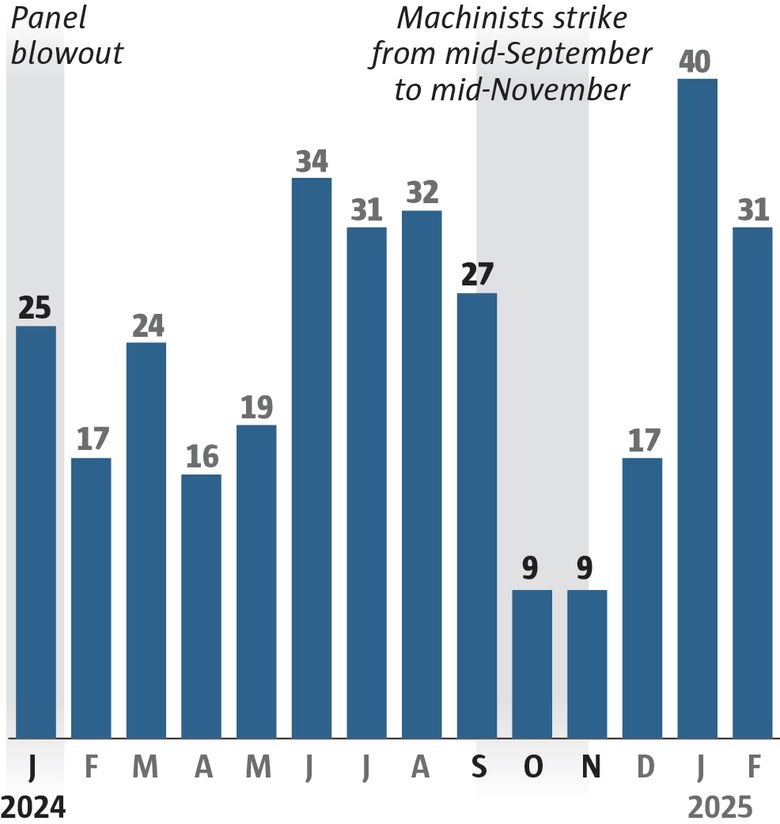

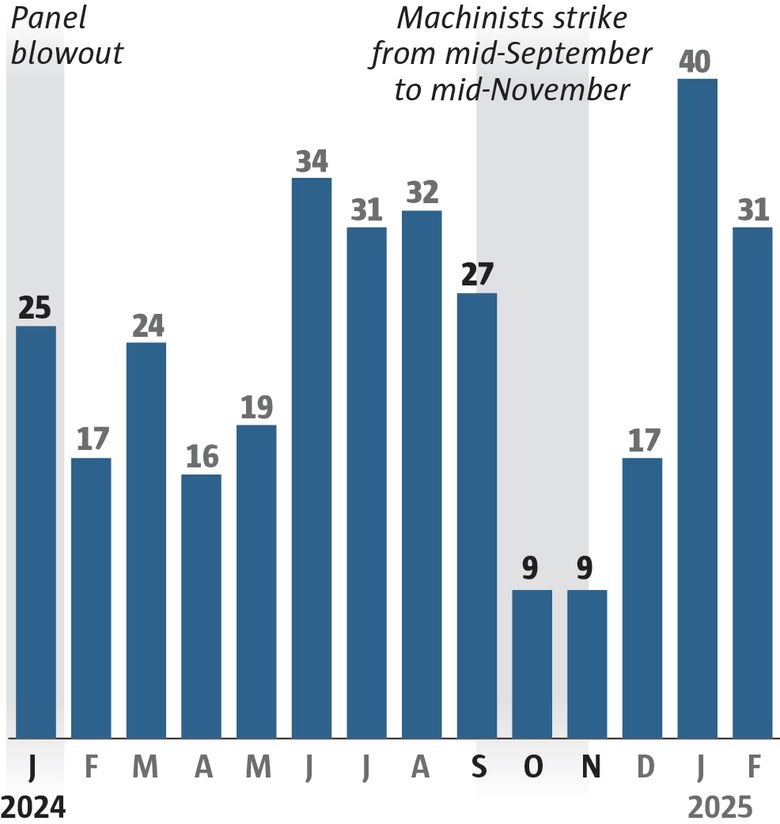

Boeing’s 737 MAX deliveries in 2024

Boeing slowed production in its factories at the start of 2024, after a panel blew off a 737 MAX plane midflight. The company has yet to reach the Federal Aviation Administration’s production cap of 38 MAX planes per month. The number of deliveries doesn’t necessarily equal the number of planes produced that month; some planes that were delivered had been mostly complete already.

Source: Boeing company data (Mark Nowlin / The Seattle Times)

In September, its ramp-up was put on hold when its Machinists workforce went on a two-month strike, halting nearly all work in the factories. Boeing restarted MAX production in December, after a pause to focus on training and certification after the strike.

This year, Boeing’s production increase continued. The company delivered 40 MAX planes in January and 31 in February, according to company data. Those numbers include deliveries of nearly done planes in storage that were handed over to buyers.

Boeing CFO West said at a Bank of America conference Wednesday that the company is making progress.

“The success factors for Boeing this year were always going to be about safety, quality and stability. And so far, we’re off to a pretty good start on all three dimensions,” West said. “The factory looks fantastic.”

“We can’t wait till, when we show stability over the course of time, that we’re then going to then be allowed to move up to higher rates beyond 38,” he continued.

After his visit to the Renton factory, Duffy said in a Fox News interview that determining when to lift the cap isn’t “an exact science.”

“It’s a bit of an art,” Duffy said. “You have to make sure the quality is there.”

“Once they do that,” he continued, “we have to take a risk on them and we’re going to have to increase the number of planes they produce.

“I’m looking forward to that day. When it’s going to come, I can’t tell you.”

Kahyaoglu, from Jefferies, isn’t worried about the cap remaining in place. The firm has already forecast production rates will stay at or below 38 MAX planes per month through December.

“It’ll be more of a continuous process,” Kahyaoglu said. “If they’re hitting these metrics and doing it safely, it will be more of a nonissue.”

Ron Epstein, an analyst with Bank of America, similarly said Boeing has some cushion before the capped production severely affects its finances. But, while it won’t mean anything dire for the company if the production cap remains, it could delay other investments, like Boeing’s highly anticipated next new airplane.

“It’s been more difficult for them to clean up their balance sheet,” Epstein said.

The news on Friday that Boeing won a contract to build the U.S. Air Force’s future fighter jet could bring some relief, Epstein said. But that depends on the terms of the contract; Boeing is losing money on several contracts it entered into during President Donald Trump’s first term.

“If their defense business is doing better, it would soften the impact of the MAX” production slowdown, Epstein said. “Right now, since they’re both not doing great, there’s nothing to soften the blow.”

Epstein doesn’t expect the end of the FAA’s production cap will happen neatly. Rather than lifting it entirely, he predicted an incremental change, adding two, four or six new planes at each consideration.

“I imagine from a quality perspective, there’s some stability they want to see,” Epstein said. “There’s no incentive for the FAA to be aggressive with it.”

Phillips, from Seattle University, agreed that the FAA will be cautious with its decision.

“They don’t want to look back and say, ‘We let them start increasing planes earlier than we should have,’ ” Phillips said. “The government, everything else being equal, wants Boeing to be a successful company in the long run.”

Lauren Rosenblatt: 206-464-2927 or lrosenblatt@seattletimes.com.

seattletimes.com |