The best case for worst case scenarios

gavin @ 26 February 2019

The “end of the world” or “good for you” are the two least likely among the spectrum of potential outcomes.

Stephen Schneider

Scientists have been looking at best, middling and worst case scenarios for anthropogenic climate change for decades. For instance, Stephen Schneider himself took a turn back in 2009. And others have postulated both far more rosy and far more catastrophic possibilities as well (with somewhat variable evidentiary bases).

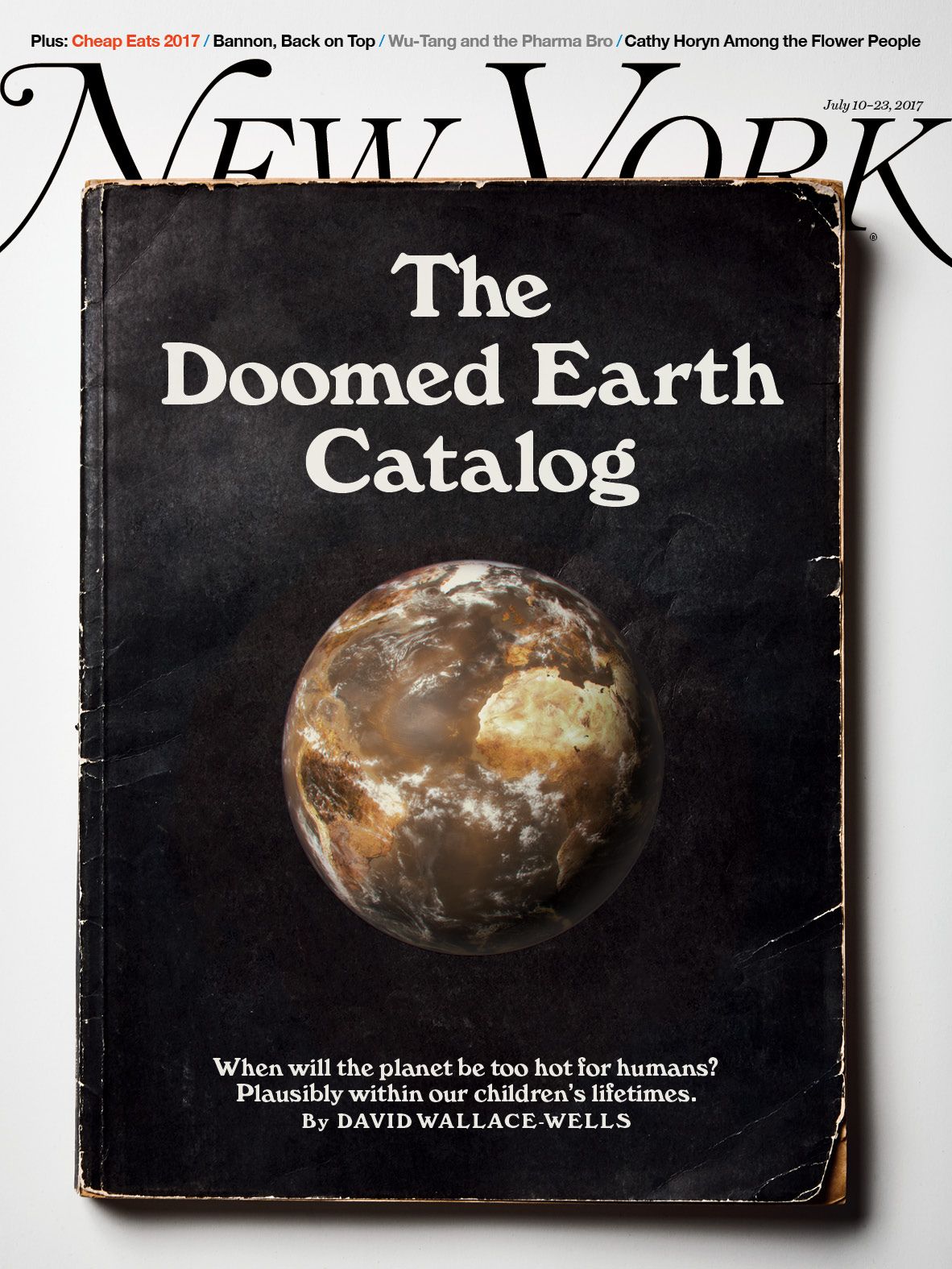

This question came up last year in the wake of a high profile piece “The Uninhabitable Earth” by David Wallace-Wells in New York magazine. That article was widely read, and heavily discussed on social media – notably by David Roberts, Mike Mann and others, was the subjected to a Climate Feedback audit, a Salon Facebook live show with Kate Marvel and the author, and a Kavli conversation at NYU with Mike Mann this week as well. A book length version is imminent.

In a similar vein, Eric Holthaus wrote “Ice Apocalypse” about worst-case scenarios of Antarctic ice sheet change and the implications for sea level rise. Again, this received a lot of attention and some serious responses (notably one from Tamsin Edwards).

It came up again in discussions about the 4th National Assessment Report which (unsurprisingly) used both high and low end scenarios to bracket plausible trajectories for future climate.

However, I’m not specifically interested in discussing these articles or reports ( many others have done so already), but rather why it always so difficult and controversial to write about the worst cases.

There are basically three (somewhat overlapping) reasons:

The credibility problem: What are the plausible worst cases? And how can one tell?The reticence problem: Are scientists self-censoring to avoid talking about extremely unpleasant outcomes?The consequentialist problem: Do scientists avoid talking about the most alarming cases to motivate engagement? These factors all intersect in much of the commentary related to this topic (and in many of the articles linked above), but it’s useful perhaps to tackle them independently.

1. Credibility

It should go without saying that imagination untethered from reality is not a good basis for discussing the future outside of science fiction novels. However, since the worst cases have not yet occurred, some amount of extrapolation, and yes, imagination, is needed to explore what “black swans” or “unknown unknowns” might lurk in our future. But it’s also the case that extrapolations from incorrect or inconsistent premises are less than useful. Unfortunately, this is often hard for even specialists to navigate, let alone journalists.

To be clear, “unknown unknowns” are real. A classic example in environmental science is the Antarctic polar ozone hole which was not predicted ahead of time (see my previous post on that history) and occurred as a result of chemistry that was theoretically known about but not considered salient and thus not implemented in predictions.

Possible candidates for “surprises in the greenhouse”, are shifts in ecosystem functioning because of the climate sensitivity of an under-appreciated key species (think pine bark beetles and the like), under-appreciated sensitivities in the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, or the North Atlantic overturning, and/or carbon feedbacks in the Arctic. Perhaps more important are the potential societal feedbacks to climate events – involving system collapses, refugee crises, health service outages etc. Strictly speaking these are “known unknowns” – we know that we don’t know enough about them. Some truly “unknown unknowns” may emerge as we get closer to Pliocene conditions of course…

But some things can be examined and ruled out. Imminent massive methane releases that are large enough to seriously affect global climate are not going to happen (there isn’t that much methane around, the Arctic was warmer than present both in the early Holocene and last interglacial and nothing similar has occurred). Neither will a massive oxygen depletion event in the ocean release clouds of hydrogen sulfide poisoning all life on land. Insta-freeze conditions driven by a collapse in the North Atlantic circulation (cf. “The Day After Tomorrow”) can be equally easily discounted.

Importantly, not every possibility that ever gets into a peer reviewed paper is equally plausible. Assessments do lag the literature by a few years, but generally (but not always) give much more robust summaries.

2. Reticence

The notion that scientists are so conservative that they hesitate to discuss dire outcomes that their science supports is quite prevalent in many treatments of worst case scenarios. It’s a useful idea, since it allows people to discount any scientists that gainsay a particularly exciting doomsday mechanism (see point #1), but is it actually true?

There have been two papers that really tried to make this point, one by Hansen (2007)(discussing the ‘scientific reticence’ among ice sheet modelers to admit to the possibility of rapid dynamic ice loss), and more recently Brysse et al (2013) who suggest that scientists might be ‘erring on the side of least drama’ (ESLD). Ironically, both papers couch their suggestions in the familiar caveats that they are nominally complaining about.

I am however unconvinced by this thesis. The examples put forward (including ice sheet responses and sea level rise, and a failed 1992 prediction of Arctic ozone depletion, etc) demonstrate biases towards quantitative over qualitative reasoning, and serve as a lesson in better caveating contingent predictions, but as evidence for ESLD they are weak tea.

There are plenty of scientists happy to make dramatic predictions (with varying levels of competence). Wadhams and Mislowski made dramatic predictions of imminent Arctic sea ice loss in the 2010s (based on nothing more than exponential extrapolation of a curve) with much misplaced confidence. Their critics (including me) were not ESLD when they pointed out the lack of physical basis in their claims. Similarly, claims by Keenlyside et al in 2008 of imminent global cooling were dramatic, but again, not strongly based in reality. But these critiques were not made out of a fear of more drama. Indeed, we also made dramatic predictions about Arctic ozone loss in 2005 (but that was skillful).

The recent interest in ice shelf calving as a mechanism of rapid ice loss ( see Tamsin’s blog) was marked by a dramatic claim based on quantitative modelling, later tempered by better statistical analysis (not by a desire to minimise drama).

Thus while this notion is quite resistant to being debunked (because of course the reticent scientists aren’t going to admit this!), I’m not convinced that there is any such pattern behind the (undoubted) missteps that have occurred in writing the IPCC reports and the like.

3. Consequentialism

The last point is similar in appearance to the previous, but has a very different basis. Recent social science research (for instance, as discussed by Mann and Hasool (also here)) suggests that fear-based messaging is not effective at building engagement for solving (or mitigating) long-term ‘chronic’ problems (indeed, it’s not clear that panic and/or fear are the best motivators for any constructive solutions to problems). Thus an argument has been made that, yes, scientists are downplaying worst case scenarios, but not because they have a personal or professional aversion to drama (point #2), but because they want to motivate the general public to become engaged in climate change solutions and they feel that this is only possible if there is hope of not only averting catastrophe but also of building a better world.

Curiously, on this reading, the scientists could find themselves in a reverse double ethical bind – constrained to minimize the consequences of climate change in order to build support for the kind of actions that could avert them.

However, for this to be a real motivation, many things need to be true. It would have to widely accepted that downplaying seriously bad expected consequences would indeed be a greater motivation to action, despite the risk of losses of credibility should the ruse be rumbled. It would also need the communicators who are expressing hope (and/or courage) in the face of alarming findings to be cynically promoting feelings that they do not share. And of course, it would have to be the case that actually telling the truth would be demotivating. The evidence for any of this seems slim.

Summary

To get to the worst cases, two things have to happen – we have to be incredibly stupid andincredibly unlucky. Dismissing plausible worst case scenarios adds to the likelihood of both. Conversely, dwelling on impossible catastrophes is a massive drain of mental energy and focus. But the fundamental question raised by the three points above is who should be listened to and trusted on these questions?

It seems clear to me that attempts to game the communication/action nexus either through deliberate scientific reticence or consequentialism are mostly pointless because none of us know with any certainty what the consequences of our science communication efforts will be. Does the shift in the Overton window from high profile boldness end up being more effective than technical focus on ‘achievable’ incremental progress or does the backlash shut down possibilities? Examples can be found for both cases. Do the millions of extra eyes that see a dramatic climate change story compensate for technical errors or idiosyncratic framings? Can we get dramatic and widely read stories that don’t have either? These are genuinely difficult questions whose solutions lie far outside the expertise of any individual climate scientist or communicator.

My own view is that scientists generally try to do the right thing, sharing the truth as best they see it, and so, in the main are neither overly reticent nor are they playing a consequentialist game. But it is also clear that with a wickedly complex issue like climate it is easy to go beyond what you know personally to be true and stray into areas where you are less sure-footed. However, if people stick only to their narrow specialties, we are going to miss the issues that arise at their intersections.

Indeed, the true worst case scenario might be one where we don’t venture out from our safe harbors of knowledge to explore the more treacherous shores of uncertainty. As we do, we will need to be careful as well as bold as we map those shoals.

ReferencesS. Schneider, "The worst-case scenario", Nature, vol. 458, pp. 1104-1105, 2009. dx.doi.org. Hansen, "Scientific reticence and sea level rise", Environmental Research Letters, vol. 2, pp. 024002, 2007. dx.doi.org. Brysse, N. Oreskes, J. O’Reilly, and M. Oppenheimer, "Climate change prediction: Erring on the side of least drama?", Global Environmental Change, vol. 23, pp. 327-337, 2013. dx.doi.org

realclimate.org |