Why Poverty Is Like a Disease

Emerging science is putting the lie to American meritocracy.

BY CHRISTIAN H. COOPER

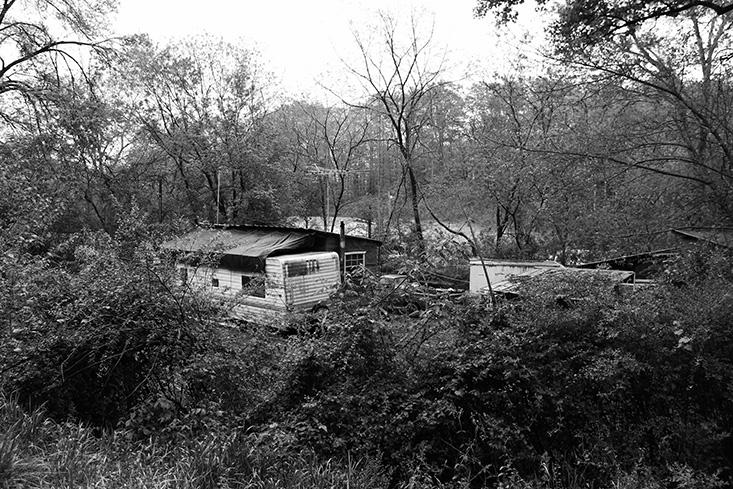

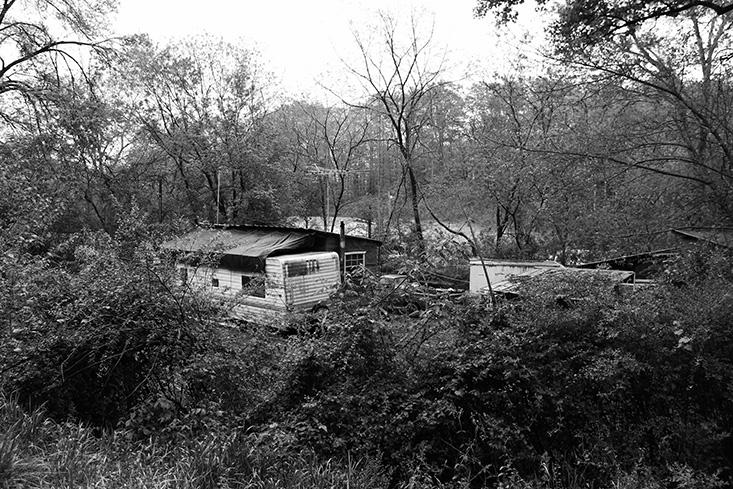

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NATHAN COOPER

APRIL 20, 2017

nautil.us

Excerpt:

...As an adult I thought I’d figured that out. I’d always thought my upbringing had made me wary and cautious, in a “lessons learned” kind of way. Over the past decades, though, that narrative has evolved. We’ve learned that the stresses associated with poverty have the potential to change our biology in ways we hadn’t imagined. It can reduce the surface area of your brain, shorten your telomeres and lifespan, increase your chances of obesity, and make you more likely to take outsized risks.

Now, new evidence is emerging suggesting the changes can go even deeper—to how our bodies assemble themselves, shifting the proportions of types of cells that they are made from, and maybe even how our genetic code is expressed, playing with it like a Rubik’s cube thrown into a running washing machine. If this science holds up, it means that poverty is more than just a socioeconomic condition. It is a collection of related symptoms that are preventable, treatable—and even inheritable. In other words, the effects of poverty begin to look very much like the symptoms of a disease.

That word—disease—carries a stigma with it. By using it here, I don’t mean that the poor are (that I am) inferior or compromised. I mean that the poor are afflicted, and told by the rest of the world that their condition is a necessary, temporary, and even positive part of modern capitalism. We tell the poor that they have the chance to escape if they just work hard enough; that we are all equally invested in a system that doles out rewards and punishments in equal measure. We point at the rare rags-to-riches stories like my own, which seem to play into the standard meritocracy template.

But merit has little to do with how I got out.... |