This is a test to see if I can successfully post a Twitter "unroll" here without having to put in a ton of work to get the formatting right.

It is easy to forget — given how many perfectly pristine photographs we see of them — that paintings are real, physical objects.

And so, like everything else in the world, they are vulnerable to deterioration, dirt, damage, and aging.

Sometimes damage is natural — paint degrades over time and colours fade.

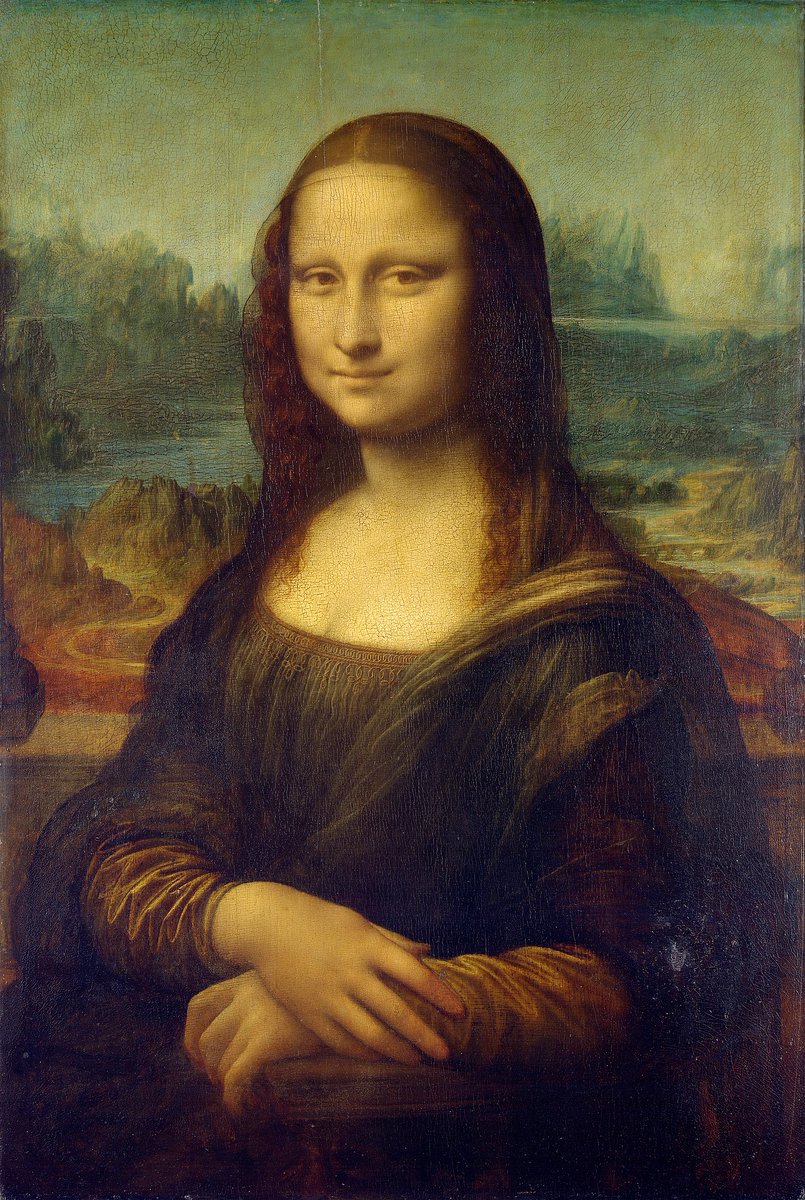

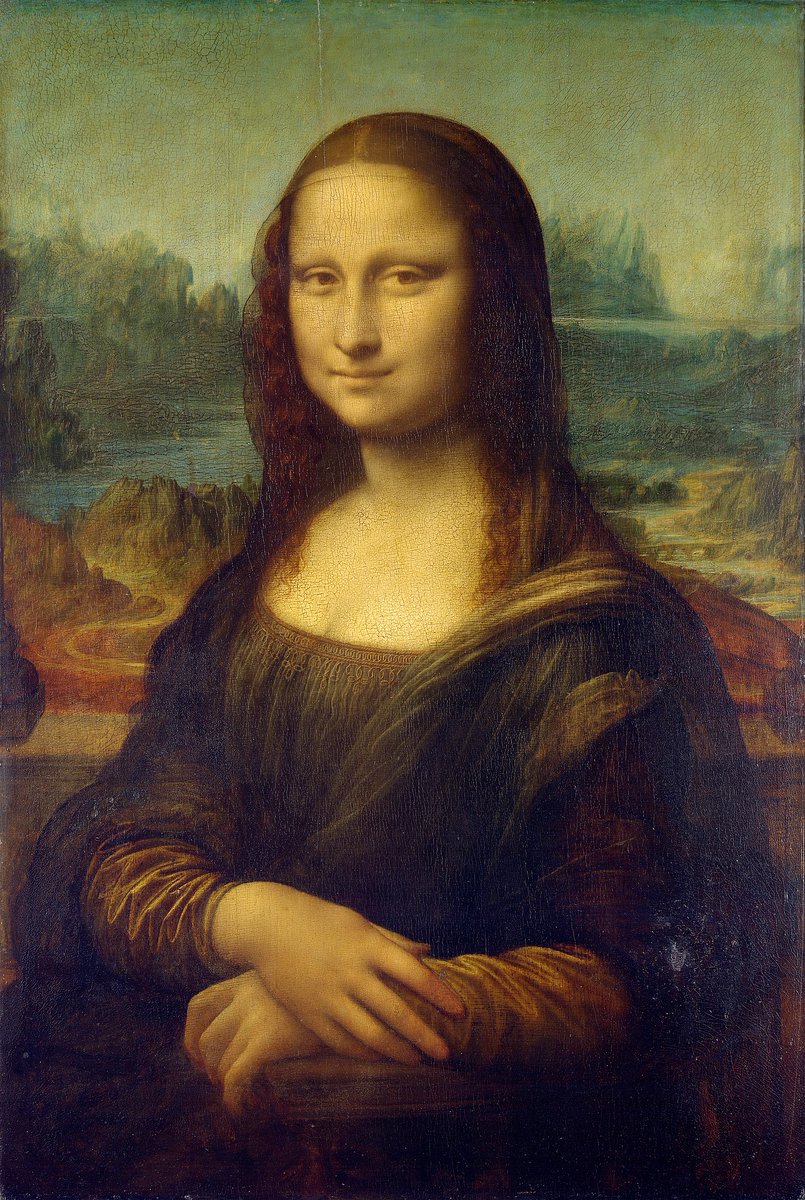

Hence the famous yellowness of the Mona Lisa, a result of various varnishes applied down the years that have since darkened.

This is not what it looked like originally.

And sometimes paintings are damaged — or changed — by intervention, intentionally or otherwise.

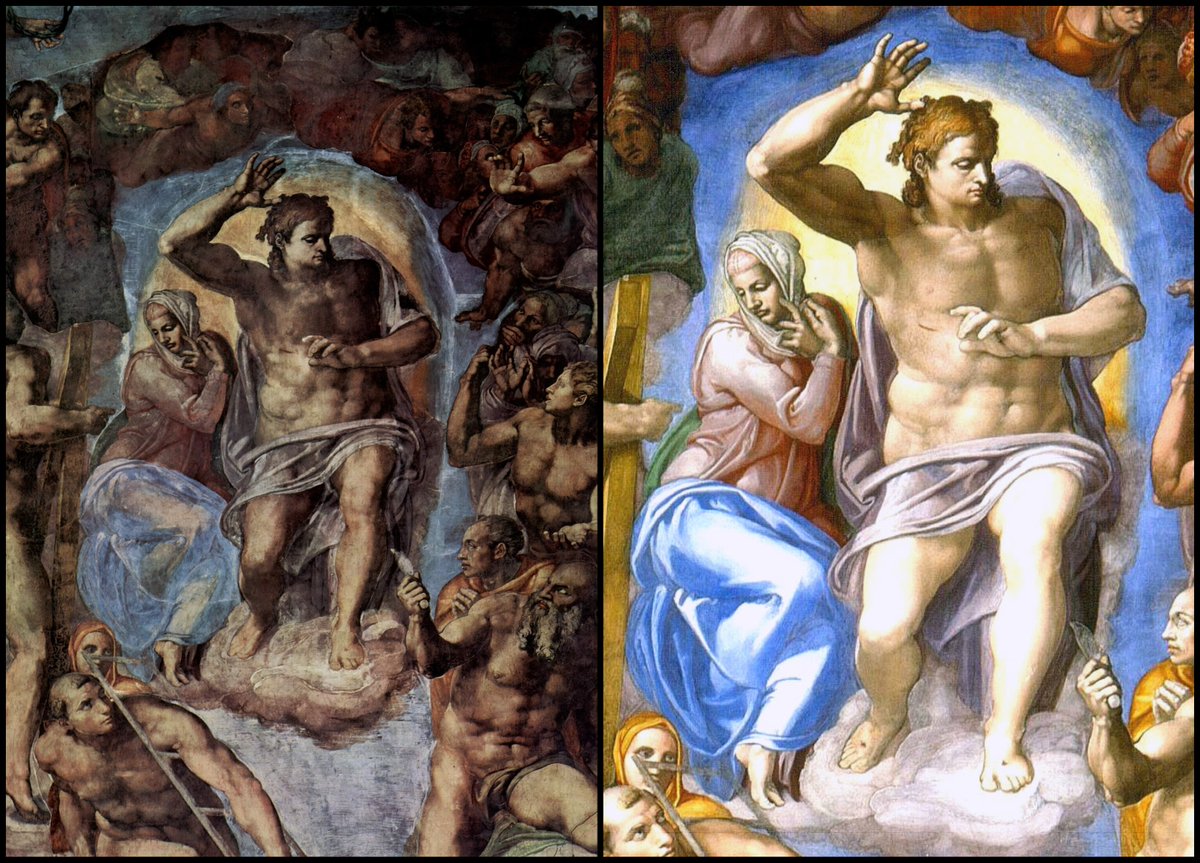

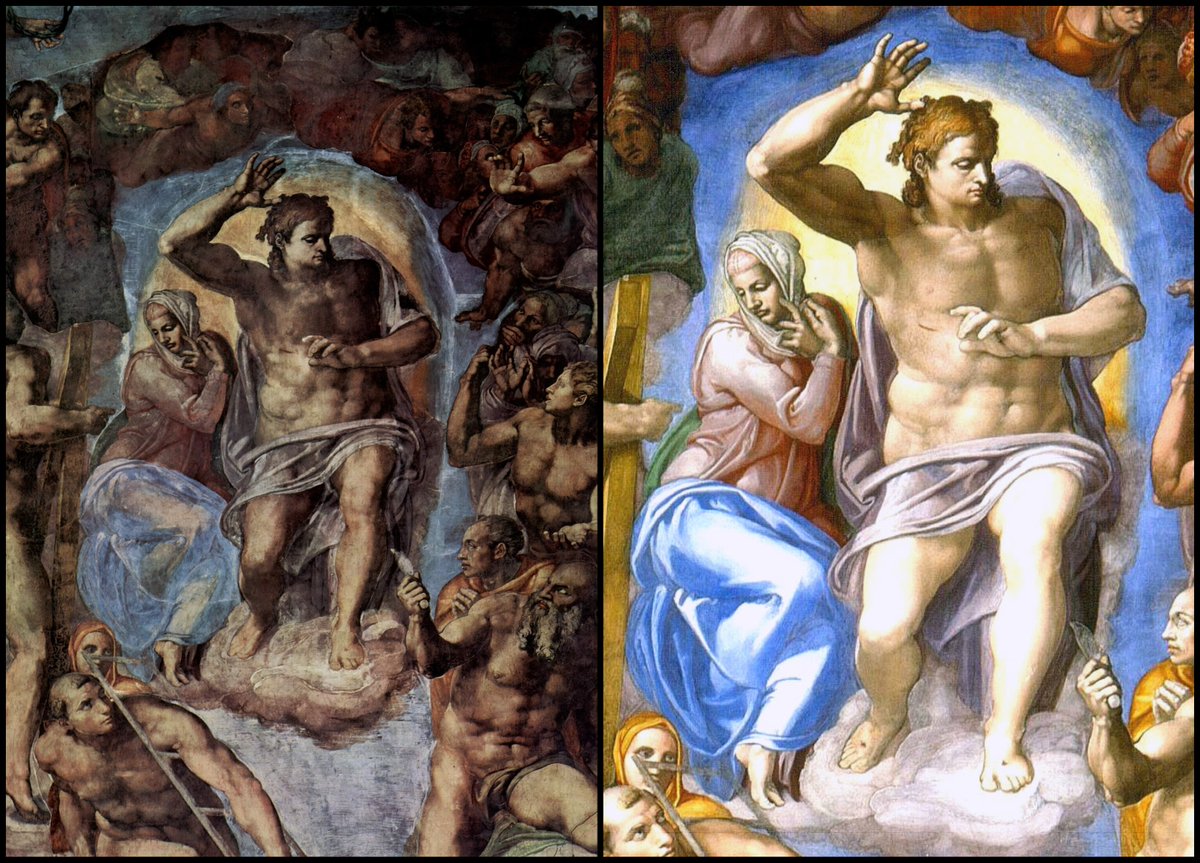

Michelangelo's Last Judgment, painted in the 1540s, was controversial because of its excessive nudity.

After Michelangelo's death Daniele da Volterra added clothes over his work:

Enter the complicated and controversial process called "restoration" — restoring art to its original condition.

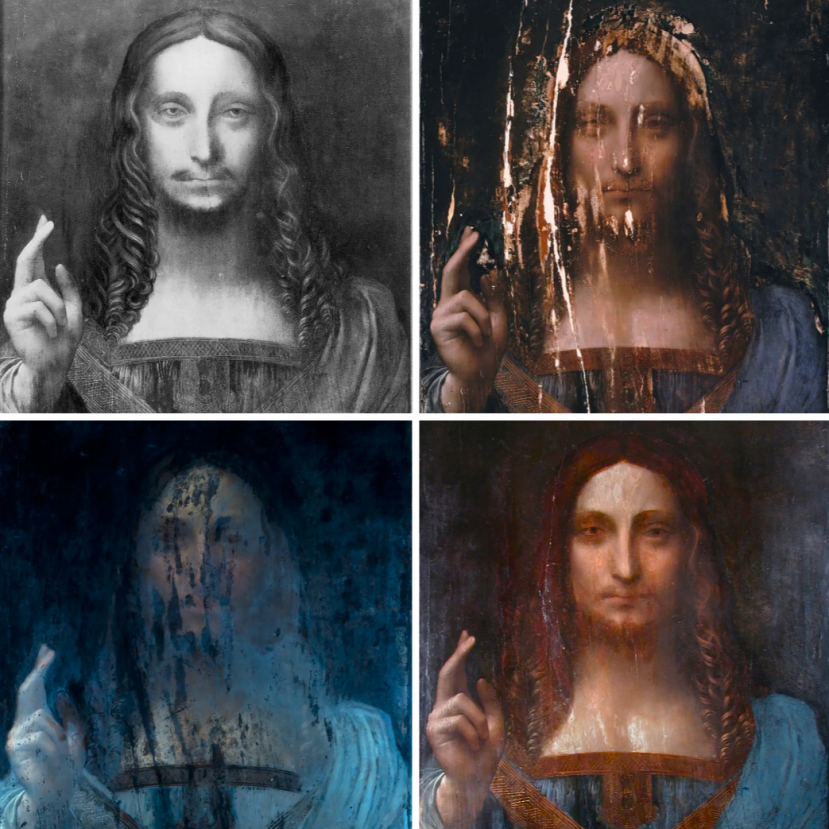

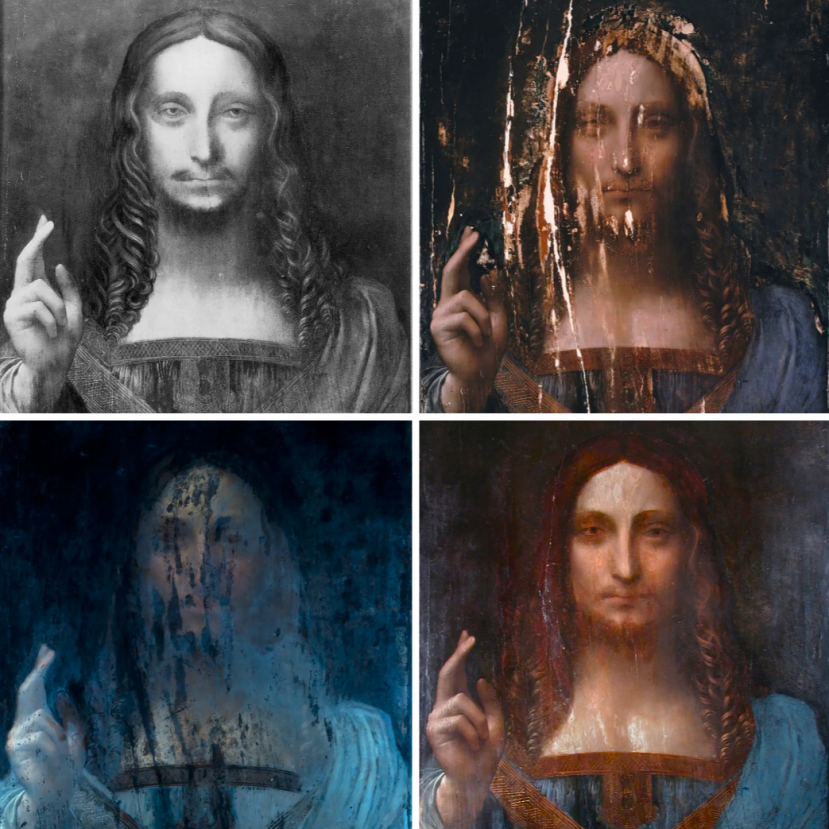

A recent example is the restoration of Leonardo's "lost" painting, Salvator Mundi, which was rediscovered, restored, and sold for half a billion dollars in 2017.

Art restoration rarely makes headline news — except when it goes disastrously wrong.

As with the now-iconic, honest attempt of a lady from Spain to restore a painting (a project she never had time to finish) in her local church:

Spain was home to another attempt that went viral a few years later, when a copy of a painting of Saint Mary by Murillo was, once again, rather oddly restored:

But these are only the most famous examples.

Restoration is more common than you might think — and more impactful.

Not long ago Leonardo da Vinci's The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne was controversially "cleaned" by the Louvre, dramatically changing how it looked.

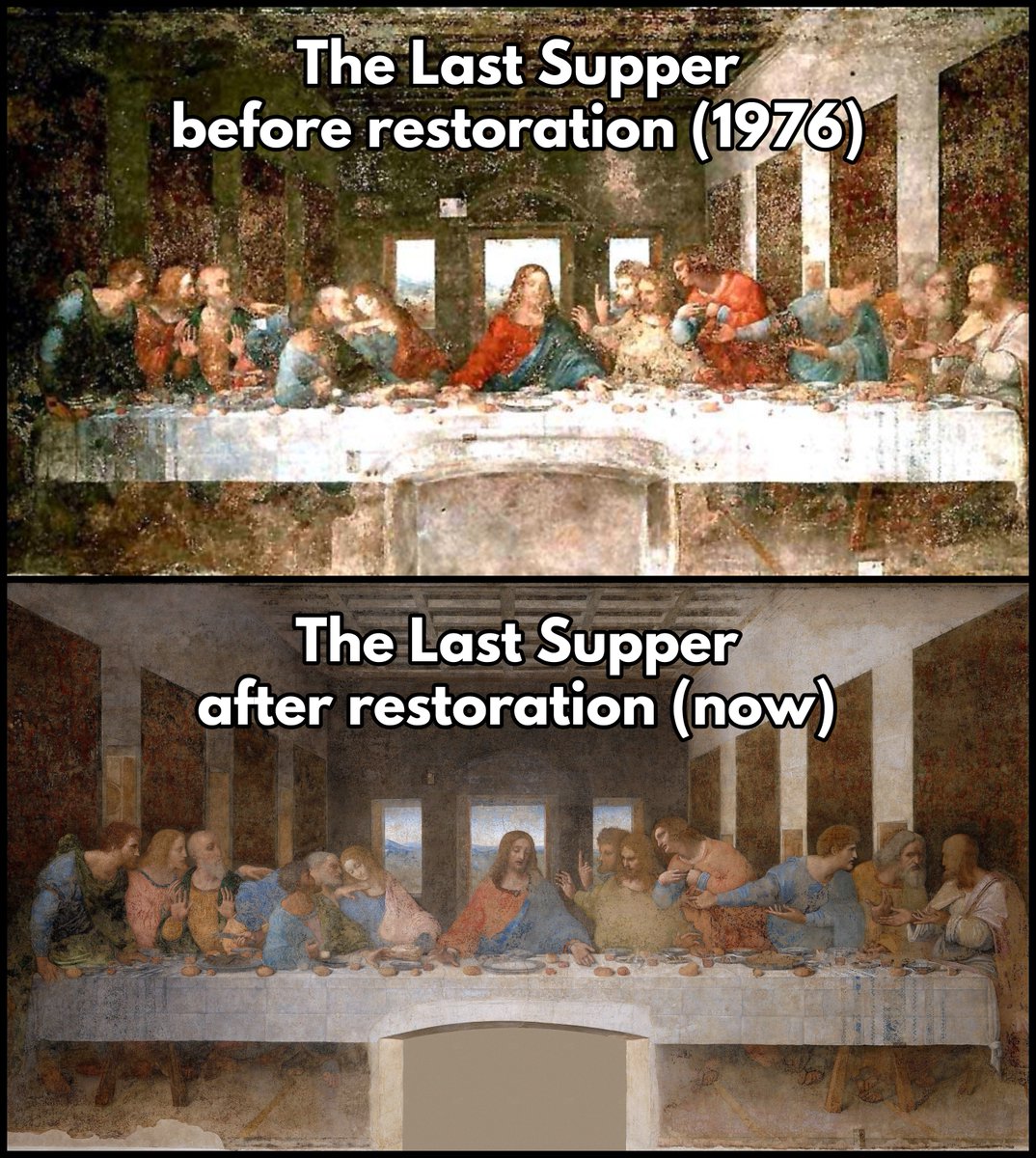

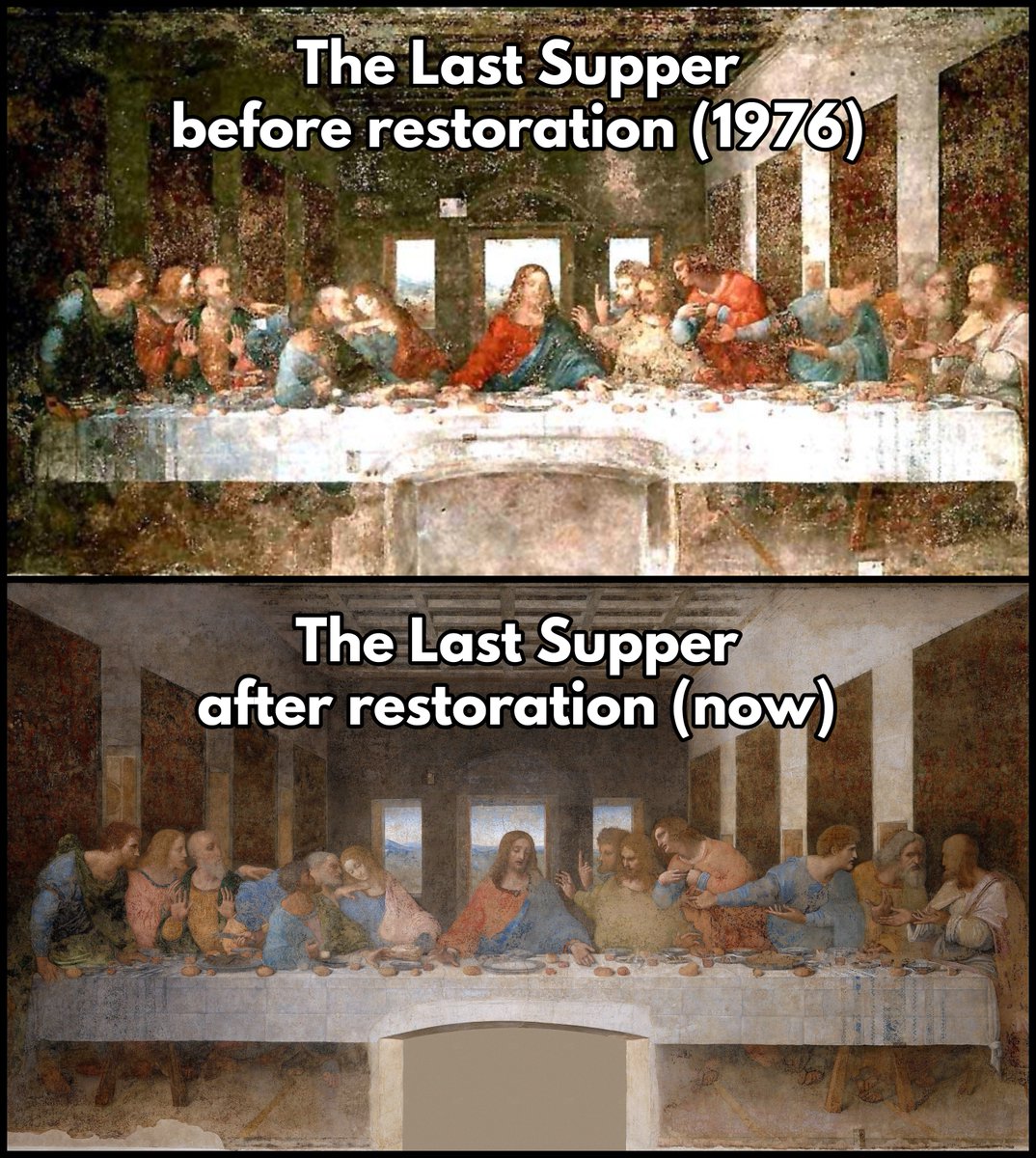

And what about Leonardo's The Last Supper?

It was painted on the wall of a refectory in Milan in the 1490s and has since been damaged, restored, damaged again, and restored again, dozens of times down the centuries.

Somebody even built a new door, destroying the feet of Jesus.

The most recent major restoration took place over twenty years, between the 1970s and 1990s, and totally transformed The Last Supper.

This is the version we are now accustomed to seeing.

Is it true to Leonardo's original work? Too much time has passed; we can simply never know.

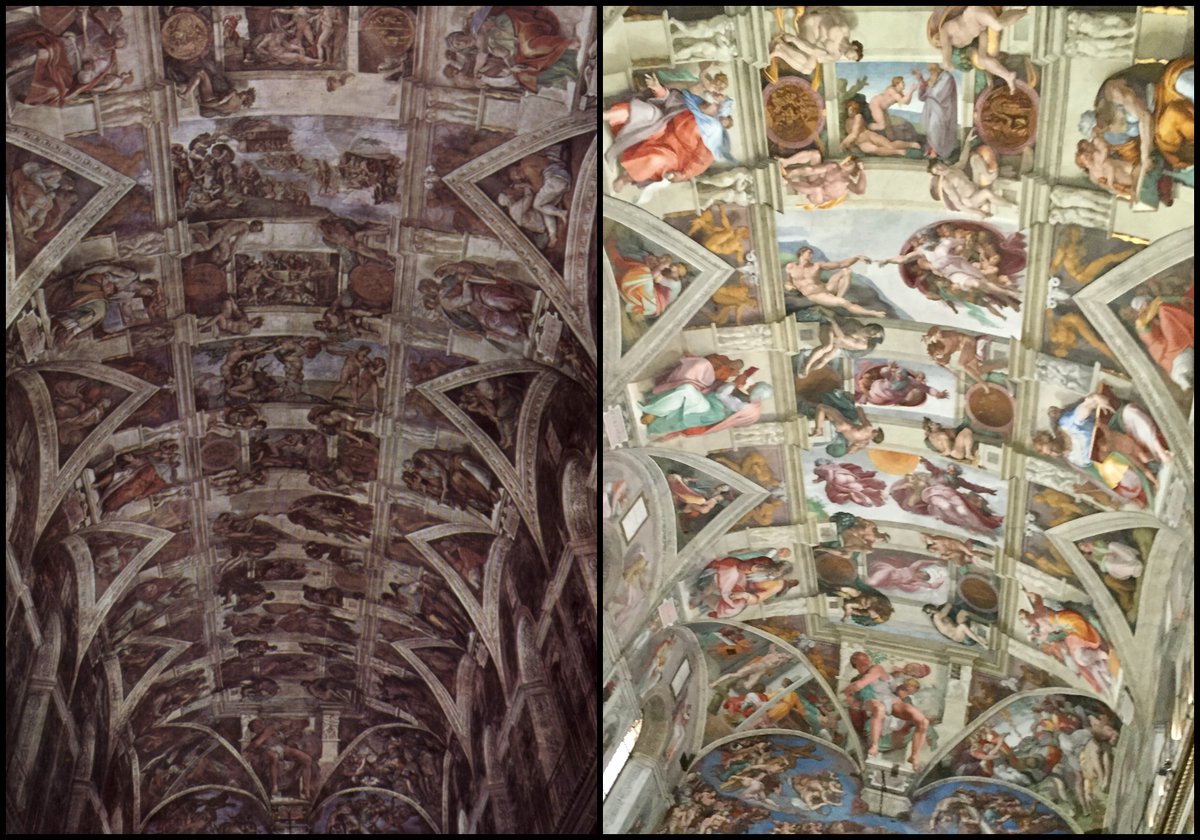

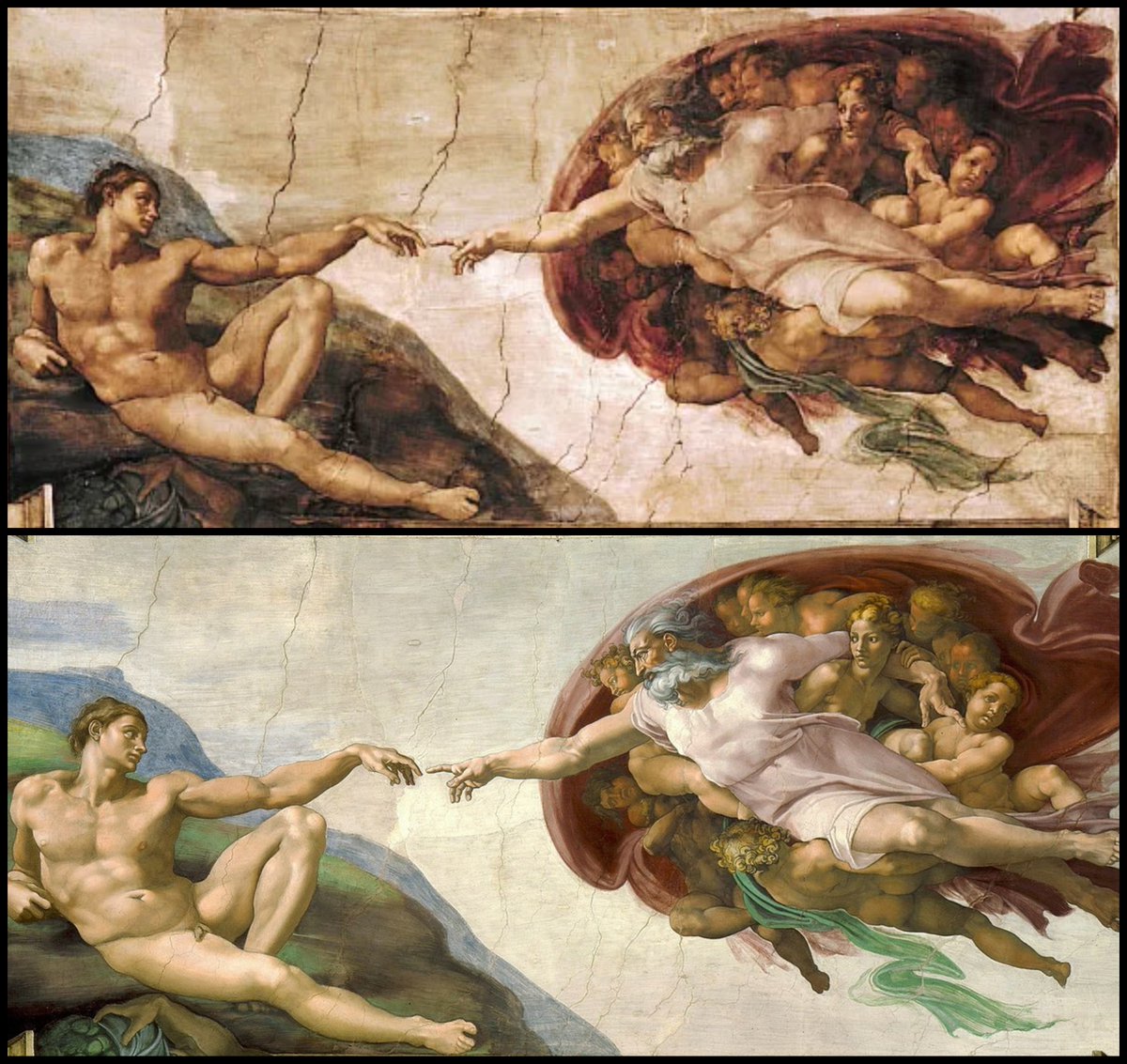

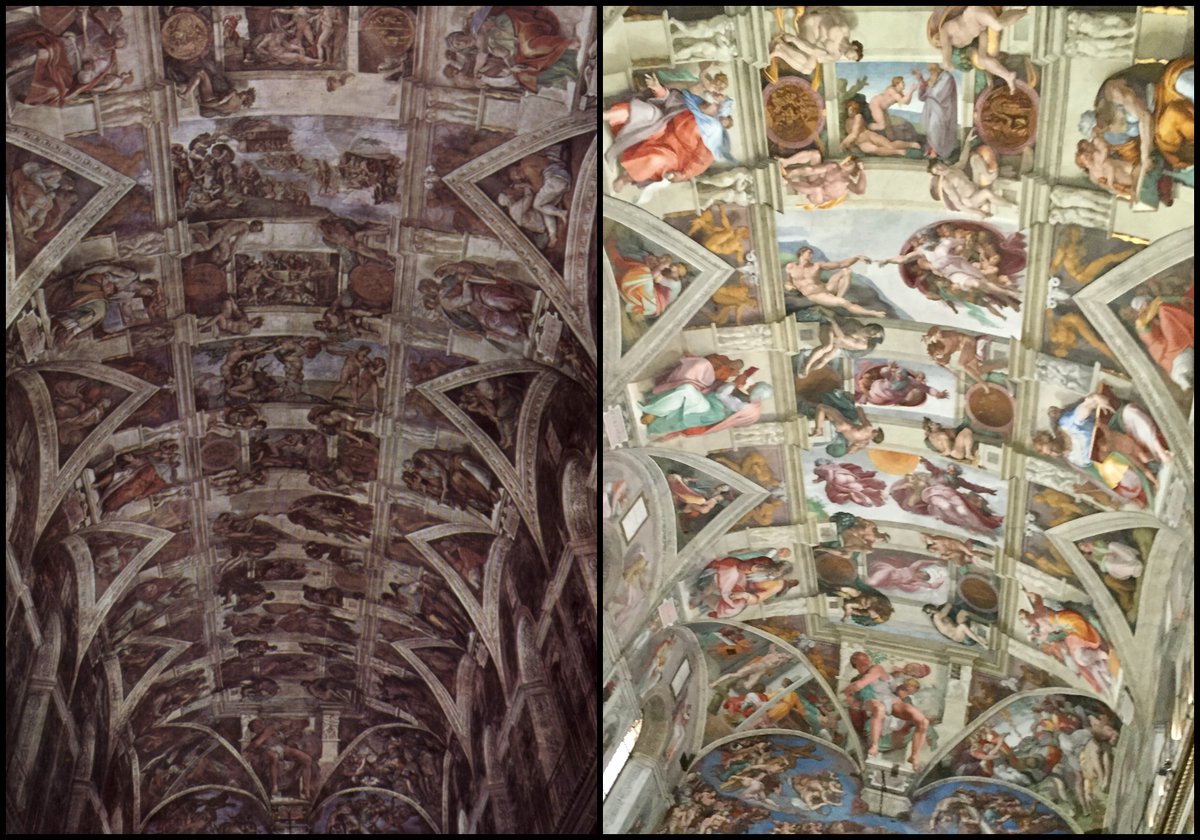

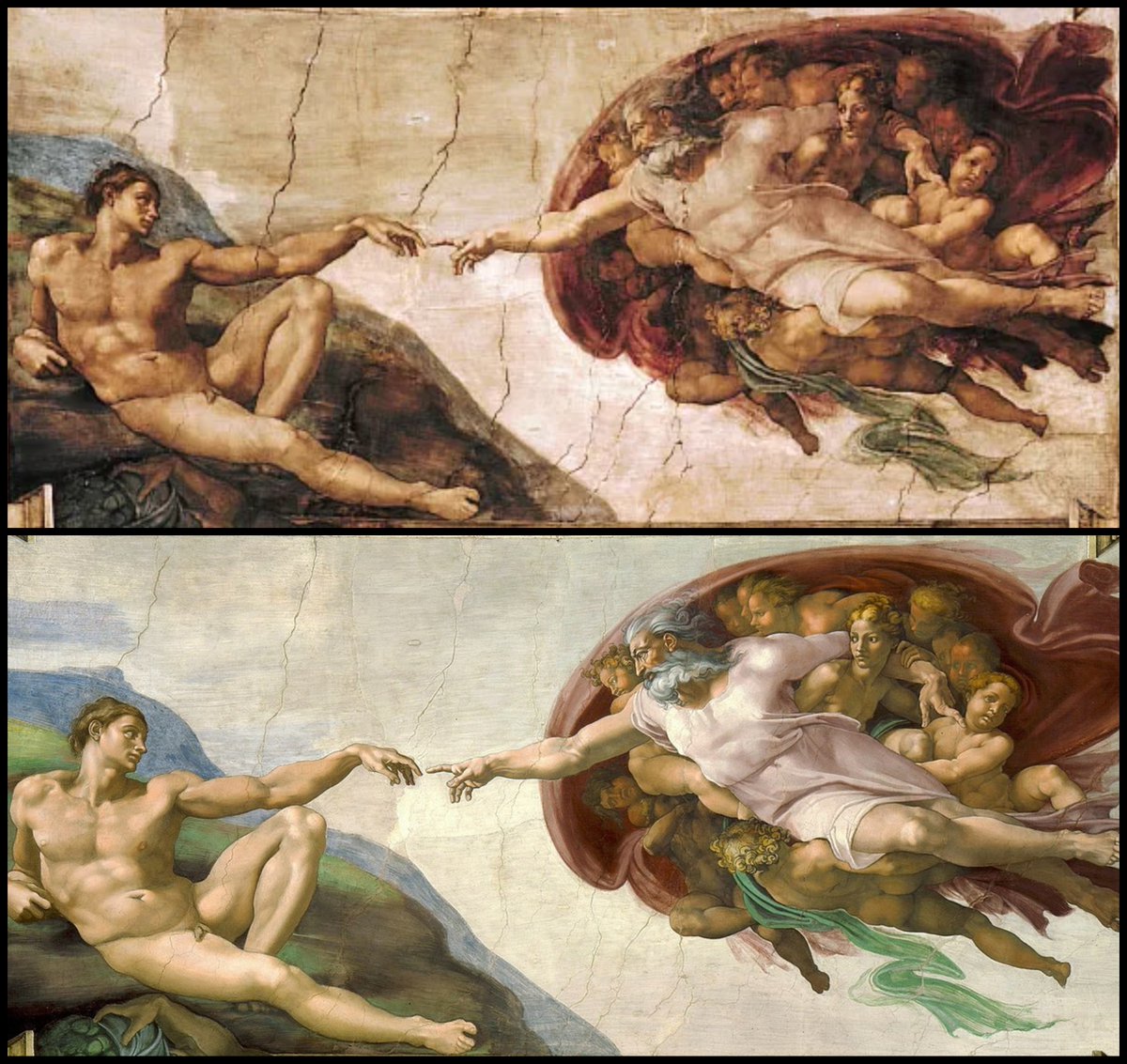

Another major example is the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, painted by Michelangelo from 1508 to 1512, now one of the world's most famous works of art.

But, until the 1990s — covered in grime, old restoration attempts, and soot from candles — it looked rather different...

This restoration was also deeply controversial.

Sure enough they brightened the ceiling, but much was removed, and some of what was removed may have been original work by Michelangelo

Notice the lack of definition in the restored version:

One particularly contentious element of the restoration was the apparent disappearance of the eyes of several figures, in this case of Jesse:

And, otherwise, critics say the restored version of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel has become too washed-out.

It may be more vivid, but subtleties of form and texture, of mood and character, have been destroyed.

A fair criticism, or not?

Michelangelo's The Last Judgment, which he painted on the wall of the Sistine Chapel three decades after he had done its ceiling, was also restored.

Remember those clothes that had been painted over to conceal nudity? Most of them were removed, despite being centuries old.

Again the result is cleaner and brighter, and we can see far more of the painting.

But has something been lost? How can we know for sure that *this* is what it was supposed to look like?

That is exactly what restorers in the past — whose work we are trying to undo — also said.

You can see why restoration is controversial.

Its supporters argue they are simultaneously preserving art and giving people what the artist originally wanted.

Its critics point out the hubris of thinking we can recreate, or even know, what somebody like Michelangelo intended.

But, more than hubris, perhaps the most dangerous part of restoration is that something, once lost, can never be regained.

Paints and pigments are extremely delicate, and whatever changes we make now cannot be unchanged in future.

Is it worth the risk?

This was why John Ruskin, arguably the greatest art historian-critic of the 19th century, fervently opposed restoration in favour of conservation.

He believed we should be grateful for whatever artworks have survived, that we should preserve them as they are instead of meddling.

Restorers are fabulously talented and dedicated people who use advanced techniques and complex scientific methods to do their work.

Take The Actor, painted by Picasso in 1905.

In 2010 somebody fell into and ripped the painting; it was restored and, now, you wouldn't know.

Restorers have also brought countless paintings back to life — like John Martin's Destruction of Pompeii, painted in 1821 but severely damaged by a flood in 1928.

It has been restored in the last decade, partly with the help of photos of the original.

A miraculous achievement.

But we don't have photographs of art from hundreds of years ago.

Instead we have to rely on scans and careful analysis of what is "original" or "fake".

As with Jan van Eyck's 600 year old Ghent Altarpiece, which was given a recent, rather eye-opening

restoration:

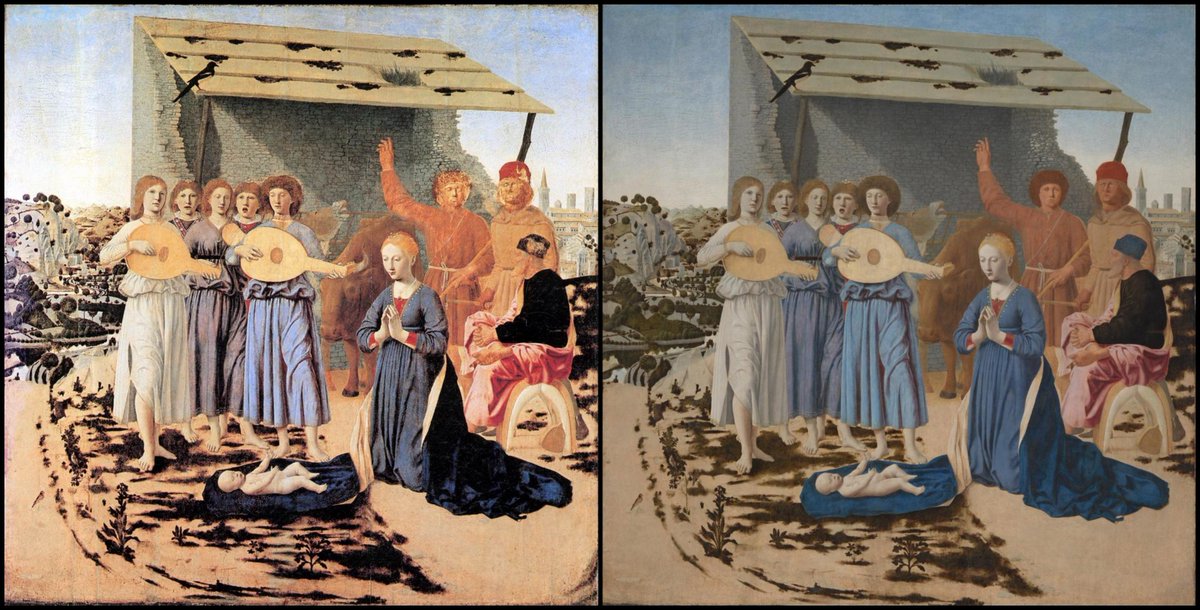

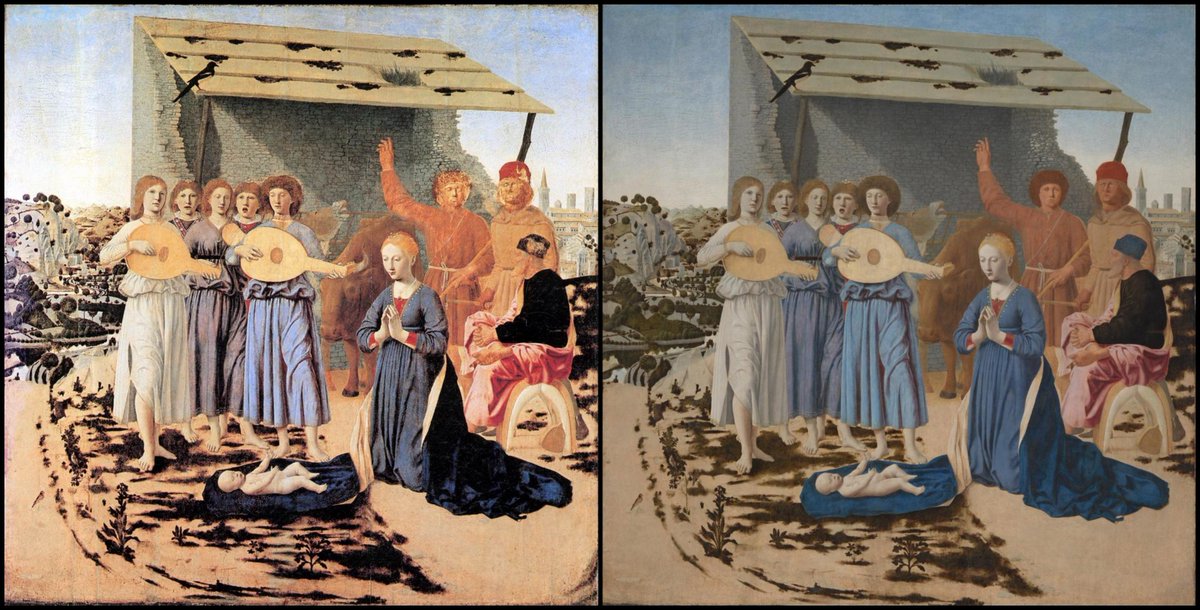

And Piero della Francesca's Nativity, painted in the 1470s, was restored just last year.

Notice the change to the faces of the shepherds on the right-hand side — was this how della Francesca originally painted it?

We will never know for sure... so should we have left it alone?

Botched restorations may be the most famous, but to critics they are no better than "effective" restorations.

What *is* a painting: pigment or intention? What is "original"? These are difficult questions, but restoration forces us to ask them.

So, should we restore art, or not?

• • • |