WA’s wildfire future: More volatile forests amid slashed budgets

Jim Henterly, a National Park Service fire lookout, uses binoculars to keep an eye on the Perry fire from Desolation Peak on Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times) Jim Henterly, a National Park Service fire lookout, uses binoculars to keep an eye on the Perry fire from Desolation Peak on Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Oct. 12, 2025 at 6:00 am Updated Oct. 12, 2025 at 6:00 am

By

Conrad Swanson

Seattle Times climate reporter

Climate Lab is a Seattle Times initiative that explores the effects of climate change in the Pacific Northwest and beyond. The project is funded in part by The Bullitt Foundation, CO2 Foundation, Jim and Birte Falconer, Mike and Becky Hughes, Henry M. Jackson Foundation, Martin-Fabert Foundation, Craig McKibben and Sarah Merner, University of Washington and Walker Family Foundation, and its fiscal sponsor is the Seattle Foundation.

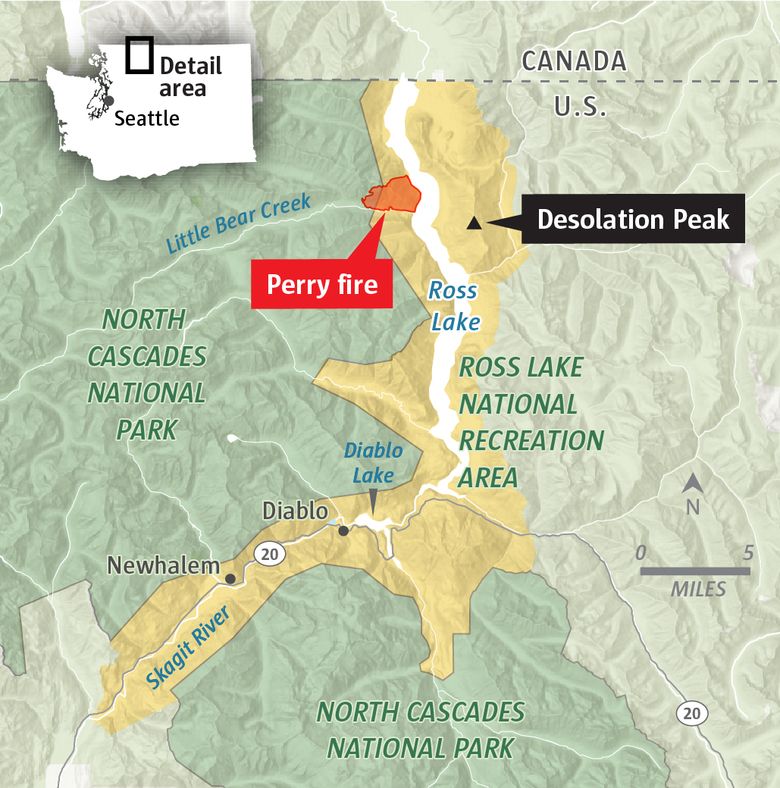

DESOLATION PEAK — A warm glow of distant flames pulsed in the mid-September night above the western shores of Ross Lake. You almost have to squint to see it.

Jim Henterly raised his black binoculars. Their lenses captured the light of the Perry fire better than the naked eye. He also kept close watch on a “sleeper” fire to the east, which was so small it hadn’t even earned an official name. If the fire grew, though, it could easily climb toward the doorstep of his cozy wooden lookout.

Years ago, Henterly and his wife joked that there would be no point in working as a wildfire lookout in Western Washington. There just wouldn’t be any action.

But that’s no longer the case. Our landscape and climate are changing, to be sure. So are we.

The Perry fire glows orange as the sun sets Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

From dwindling mountain snowpack and desiccated blueberry patches to disappearing critters, colleagues and resources. Henterly, 71, has not only watched these changes unfold, he’s felt them. For decades, this lone lookout has spent his summers in a sort of Thoreauvian dream, hooked on the lifestyle, the camaraderie, the sense of purpose. For even longer, people across the American West shared another dream, in which they thought it possible to stave off the threat of wildfires indefinitely. But both dreams must eventually end.

The Seattle Times sought out Henterly’s company on this peak, alongside the insight of public officials and wildfire experts, to understand the scope of our growing wildfire risk and to illuminate the years ahead.

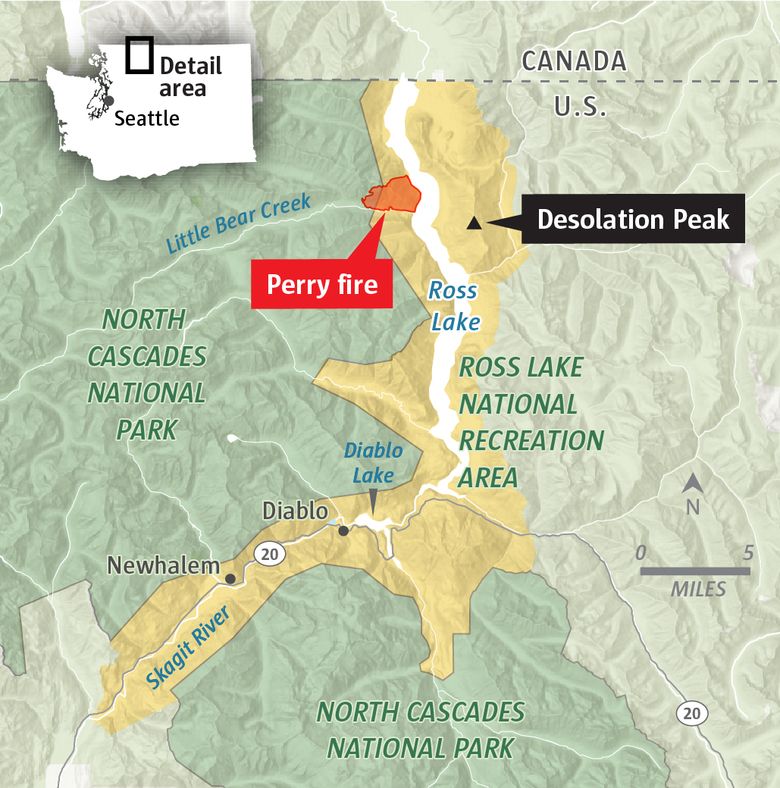

Sources: Esri, National Interagency Fire Center (Chris Kaeser / The Seattle Times)

High-profile wildfires in recent years warn of future blazes west of the Cascade crest, where most of Washington’s people live, fire ecologists say. And while money and staffing for lookouts have declined steadily over the decades, this year the federal government hastened its retreat on virtually every other front.

Washington state, reeling from cuts to bridge a $16 billion budget hole, must now face much of the increasing danger alone, and it can’t keep dodging bullets forever.

Danger looms year-round across many of the Western states now. Just look at the wildfires in California, Henterly said.

“They’re endless,” he said. “And they’re everywhere at once.”

Jim Henterly dials in an Osborne Fire Finder last month from his Desolation Peak lookout. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

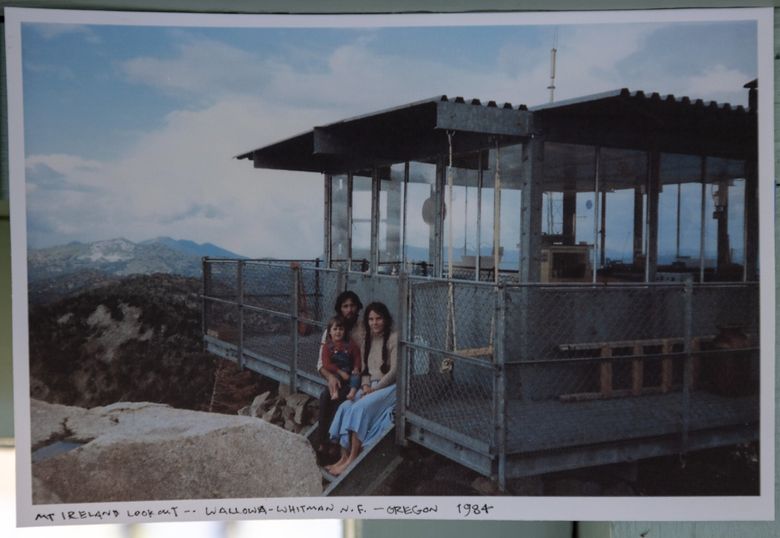

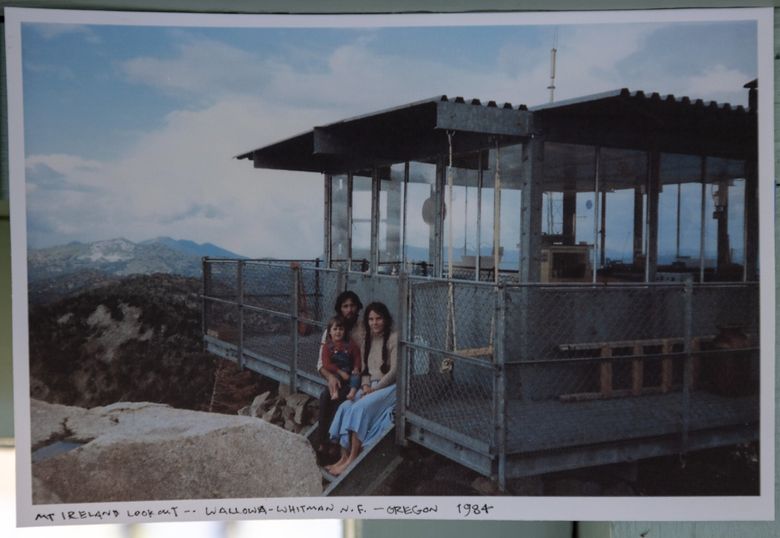

A photo from 1984 shows Jim Henterly with his wife, Ann Marie, and daughter Lael at the Mount Ireland fire lookout in Oregon’s Blue Mountains. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

The Desolation Peak fire lookout sits at 6,102 feet above sea level in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times) The Desolation Peak fire lookout sits at 6,102 feet above sea level in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

He’s seen his fair share from this perch 6,102 feet above sea level, plenty of them close enough to belch their smoke straight into his face. This summer, flames across Ross Lake were so widespread that the mountainside appeared to hold a small city, Henterly said. The Perry fire has since calmed, though smoldering trees and logs remain.

For the briefest of moments, the small sleeper fire to the east flared. A speck of flame appeared on the slopes of Skagit Peak and flickered in the breeze before withdrawing once more into a charred tree.

These things can sneak up on you if you’re not careful.

Related

From 2022: Few fire lookout towers remain in WA. What’s it’s like to live in one?

48.91° N, 121.02°

WDesolation Peak is perhaps the most famous wildfire lookout in the business, having hosted the likes of Jack Kerouac and poet Gary Snyder. There’s a certain mysticism to the remote mountaintop and its panoramic views of the lake, Nohokomeen Glacier and the jagged Hozomeen Mountain.

Hozomeen Mountain towers over the landscape. Also, the Milky Way appears over the Desolation Peak… (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Up top, hikers seeking an adventure or spiritual experience will find Henterly, a veteran lookout of more than 30 summers, the last decade of which have been spent on Desolation. In the offseason, he works as a firefighter and emergency medical technician in rural Whatcom County, where he lives. On top of the mountain, he’s both of those things, alongside a fire spotter, radio relay, guide, historian, philosopher and brand ambassador.

Henterly is soft-spoken and warm, harboring a sense of wonder for the natural world. Eager to share the mountain’s lore or history of wildfires. From his vantage point, he peers deeper into this world than most.

Job security’s always been a little touch and go, said Henterly, who is a seasonal U.S. Forest Service worker. But federal funding is now at its most precarious point in decades. He can’t yet say whether he’ll be asked back for another year.

Most Read Local Stories

Less money

Pessimism is seeping into every facet of the wildland firefighting industry, which struggles for money, staffing, data and other resources.

The single largest challenge stems from Olympia, said Public Lands Commissioner Dave Upthegrove.

In an attempt to bridge the state’s $16 billion budget shortfall for the next four years, lawmakers cut $125 million that had been promised per biennium for wildfire response and preparedness.

Those cuts kick in next year and wildfire programs will have $40 million to spend, two-thirds of their budget this year, Upthegrove said. The year after, they’ll have half as much.

That will mean fewer prescribed burns, less forest thinning, less grant money for local crews, who are generally first on the scene for wildfires, Washington state Forester George Geissler said.

The cost-saving measures might not pan out. Guarding against wildfires ahead of time will always be more affordable than fighting or recovering from them, Upthegrove said. In October, he noted that just two of the state’s largest wildfires still burning each cost about $1 million a day to fight.

A stream is choked by charred remnants from the Labor Mountain fires near Cle Elum on Oct. 1. (Kevin Clark / The Seattle Times)

As global warming and drying trends deepen, wildfire danger reaches deeper into major urban areas, as the country saw in Los Angeles; Lahaina, Hawaii; and Louisville, Colo. Here in Washington, Upthegrove said, places like Snoqualmie, North Bend, Redmond and Issaquah worry him in particular.

The overarching fire management effort, by definition, requires close coordination between state and federal agencies, he said, and President Donald Trump’s administration has been uncommunicative and unpredictable.

So far this year, the federal government has fired more than 3,400 from the Forest Service and 1,000 from the Park Service. Some 4,500 firefighting jobs remained unfilled at the height of the season, ProPublica reported.

Out of next year’s budget, the Trump administration wants to slash nearly $1.4 billion of the Forest Service’s management, operations, conservation and research allocations and $900 million from the National Park Service. A proposal to absorb Forest Service firefighting operations within the Department of Interior would eliminate $2.4 billion, High Country News reported.

An Interior spokesperson said in an email that the administration is working to streamline its hiring process and strengthen pay and retention for wildland firefighters but offered few additional details.

The administration also continually attacks the broad scientific consensus of global warming, itself a substantial factor in our worsening wildfires, and has called for the elimination of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Fire burns through brush during prescribed-burn training in May 2 near Roslyn. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Put together, said Timothy Ingalsbee, a wildland fire ecologist based in Eugene, Ore., the Trump administration is dismantling the country’s resources to guard against, fight and recover from wildfires at a time when the risk is increasing. And it’s putting much more pressure on states that aren’t financially capable of making up the difference.

“We are running fast in the wrong direction,” Ingalsbee said.

The gap between science and contemporary fire management is huge and growing, said Ingalsbee, who also heads the nonprofit Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology.

Where are you, marmots?

A pair of ravens hopped and played in the breeze atop Desolation Peak as Henterly watched from behind a pane of glass. He’s watched them for years now, same as the bears foraging through the blueberry patches down the mountain.

Henterly wouldn’t call himself part of the wildlife community on this mountain. Rather, he’s an observer. And a keen one, at that. He knows when something’s missing, like the marmots.

The furry creatures disappeared over the past couple of years, driven away by warming winters, rising tree lines and increased predation.

Waving a hand over the mountain panorama, Henterly will point out portions of the forest ravaged by western spruce budworm, followed by beetle kill.

Extreme cold or wildfire are the best bets to kill the devastating insects en masse, he said. And these days, it’s much more likely to be a wildfire, which also thrives on the dead and dying foliage, he said.

A black bear forages on wild blueberries Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

More fires

Washington now sits on the tail end of its third year of severe drought in a row, leaving densely packed trees and shrubs dry and primed for wildfire.

Public officials braced for the worst at the start of the summer but so far their fears haven’t materialized. To date, wildfires across the state have burned through some 392 square miles of forest (more than 4.5 times the footprint of Seattle).

This year’s burn area is well under the 10-year average of 730 square miles, said Ryan Rodruck, a spokesperson for the state Department of Natural Resources. But the number of fires is about 15% higher than the long-term average.

Part of the reason for such a low burn area, Rodruck said, is that our firefighters are quite adept at extinguishing wildfires.

Putting out fires is only part of the equation, though, said Susan Prichard, a wildfire ecologist with the University of Washington. Suppressing them entirely only serves to delay the inevitable and allow fuels to accumulate, increasing the risk for massive and devastating wildfires where before only small ones would historically have burned.

Fires in the dense and wet forests of Western Washington are much less common, Prichard said. But they hold much greater destructive potential.

The Bear Gulch fire has left burn scars in the forest on the north side of Lake Cushman. (Erika Schultz / The Seattle Times)

One harbinger of their increasing prevalence in Western Washington is the human-caused Bear Gulch fire, Prichard said. It sparked on July 6 and still burns today, the largest blaze west of the Cascades. To date, it has consumed more than 32 square miles but hasn’t yet killed anybody or destroyed any buildings.

Had Bear Gulch combined with high-speed winds, especially those that can intermittently come from the east, its potential to spread far and wide would have multiplied, Prichard said. The recipe reminded her of the 2020 Labor Day fires in Oregon, which killed 11 and destroyed more than 4,000 homes.

In many ways, Western Washington lucked out, she said.

As the number of fire ignitions continues to rise, each new fire represents a roll of the dice, said Michael Medler, a former wildland firefighter and pyrogeography researcher at Western Washington University. Chances of a major fire in Western Washington might be low in a given year but they’re growing.

Crew members work in late August to improve access for firefighters during the Bear Gulch fire near the north side of Lake Cushman. (Erika Schultz / The Seattle Times)

The paradigm brings to mind Hurricane Katrina, Medler said. In the aftermath, then-President George W. Bush claimed that nobody anticipated New Orleans’ levees breaching in the storm surge.

Sure they did, Medler said. Anybody who thought about it for an hour anticipated the breach.

“That’s where we’re at. Who could anticipate a $5 billion west-side Cascades fire? Everyone who’s thought about it,” said Medler, referencing the potential cost of damages from such a blaze.

Outlook from up topHenterly’s under no illusions about the current state of affairs. Plenty of time to consider the angles on his mountain peak.

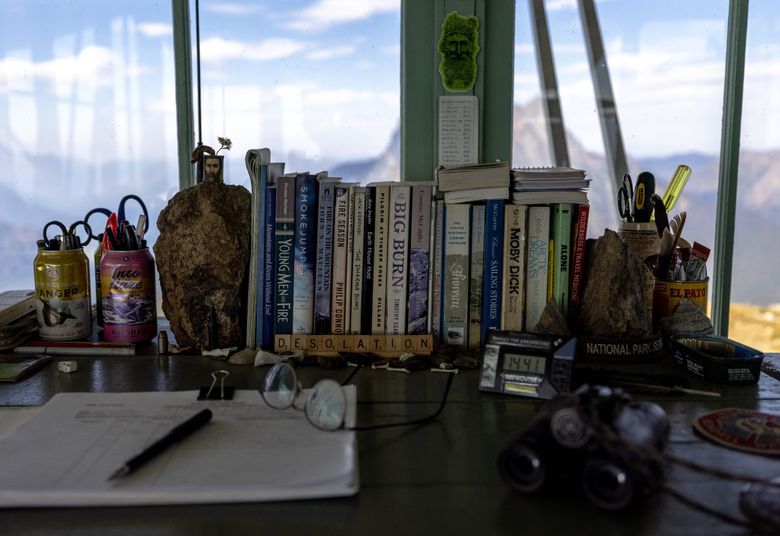

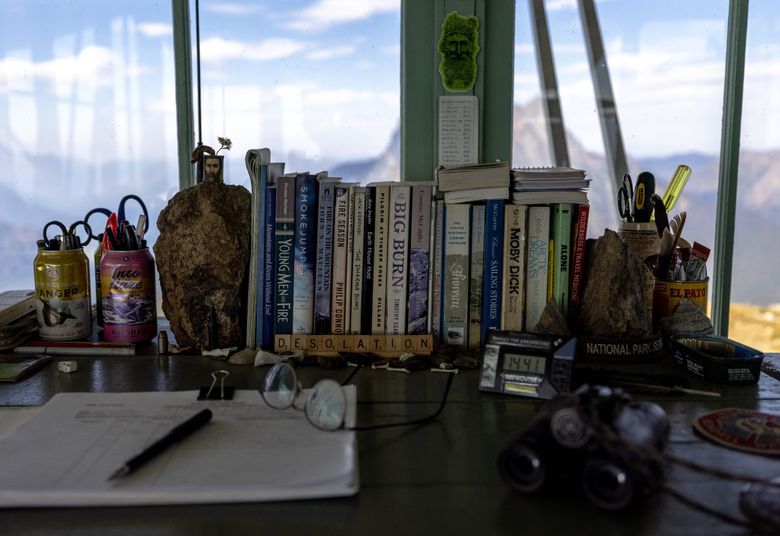

He spends much of his time in isolation, surrounded by books and collecting quotes mentioning “desolation.” He’ll pin them up around his 14-by-14 home, alongside portraits he’s drawn of Henry David Thoreau, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, John Muir and Treebeard. He also has a special affinity for the ill-fated explorer Ernest Shackleton.

A daily log, books and more tidbits belonging to Jim Henterly sit on a desk inside the Desolation Peak lookout in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Some of the sketches he’s turned into stickers and he’ll thrust a handful in your direction, keepsakes for later. He’ll draw in the margins of a guest book he keeps, encouraging visitors to leave notes of their own. He’s kind and energetic, eager to share a laugh and taking comfort in the sporadic company of hikers and seekers.

No, Henterly doesn’t project an air of pessimism, nor would he want anyone to leave the mountain in despair. Not all news is bad news. Nor is every fire something to fear.

Good fire

For one example of good fire, just look west across Ross Lake toward the smoldering Perry fire. Through the tail end of summer, the burn area remained relatively small, crossing paths with previous burn scars on the landscape. It was sparked by lightning rather than by humans, who are responsible for an estimated 90% of wildfires.

Smoke from the Perry fire billows out of a valley as seen from Desolation Peak on Sept. 14 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Park officials are comfortable allowing this particular fire to progress (mostly) organically, still moving to protect buildings and infrastructure in the area, Henterly said.

North Cascades National Park has served as a leader in this space by — whenever practical — allowing wildfires to resume their restorative ecological role, Prichard said. The Sourdough fire in 2023 might be another example of a healthy wildfire in the park, she said, though officials did struggle to protect Seattle City Light’s electrical infrastructure in the area.

Once a wildfire burns through an area, it provides a sort of reset, Prichard said. Fires have been a regular part of the region’s ecosystem for millennia, whether lighted naturally or by Indigenous people. Return fires are less likely to burn with such intensity because there’s less fuel.

This is not to say every wildfire should be left to burn as it will but, wherever possible, the big picture should be considered, Prichard said.

Every fire’s unique, Henterly said, and each can teach a different lesson.

Even after spats of rain showered over the North Cascades, he continued to glance toward his sleeper fire every so often, just to make sure it wasn’t gaining ground.

People have been forecasting the end of Henterly’s career for decades. One fire management officer in the 1980s warned that human lookouts would soon be replaced by technology.

Jim Henterly keeps an eye on the Perry fire from the Desolation Peak fire lookout in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Recalling the story, Henterly cast a wry look skyward, thinking of his former supervisor.

“I’m still here, Jerry,” he said.

Henterly’s not giving up, and he wouldn’t want you to either. We humans have a pretty good gig going here on Earth, he said. It won’t last forever but it’d be nice to keep it going a little longer.

Conrad Swanson: 206-464-3805 or cswanson@seattletimes.com. Conrad Swanson is a climate reporter at The Seattle Times whose work focuses on climate change and its intersections with environmental and political issues.

seattletimes.com |

Jim Henterly, a National Park Service fire lookout, uses binoculars to keep an eye on the Perry fire from Desolation Peak on Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

Jim Henterly, a National Park Service fire lookout, uses binoculars to keep an eye on the Perry fire from Desolation Peak on Sept. 13 in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

The Desolation Peak fire lookout sits at 6,102 feet above sea level in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)

The Desolation Peak fire lookout sits at 6,102 feet above sea level in North Cascades National Park. (Nick Wagner / The Seattle Times)