How Zynga went from social gaming powerhouse to has-been

Gaming giant has been on a wild ride in just 5 short years—while losing $600M.

by Cyrus Farivar

ars technica

Sept 12 2013, 8:00am CDT

Aurich Lawson / Zynga

In Zynga's July 2011 prospectus to future shareholders, company founder and CEO Mark Pincus outlined his firm's ambitious plan to take over the gaming world.

"My kids decided a few months ago that peek-a-boo was their favorite game," he wrote. "While it's unlikely that we can improve upon this classic, I look forward to playing Zynga games with them very soon. When they enter high school, there's no doubt that they'll search on Google, they'll share with their friends on Facebook, and they'll probably do a lot of shopping on Amazon. And I'm planning for Zynga to be there when they want to play."

Will it? At the time, Pincus had ample reason for confidence. Zynga was riding high after several years of success. Since its July 2007 founding, Zynga raked in hundreds of millions of dollars in venture capital, launched massive hits like FarmVille, Mafia Wars, and CityVille, and turned a 2010 profit of $90.5 million. It was also on an acquisition binge, picking up 11 companies in as many months between 2010 and 2011.

But even as the prospectus was published, Zynga's star was losing its luster. For one thing, profitability was an aberration; 2010 was the only year that Zynga made a profit, and since 2008 the company has sustained a net loss of just under $600 million.

Then there was the company's stock. After the December 2011 initial public offering (IPO) at $9.50 per share, the stock price rose as high as $14.69 on March 2, 2012. It's been on a steady decline since. As of this writing, the stock price is hovering around $3.00 per share.

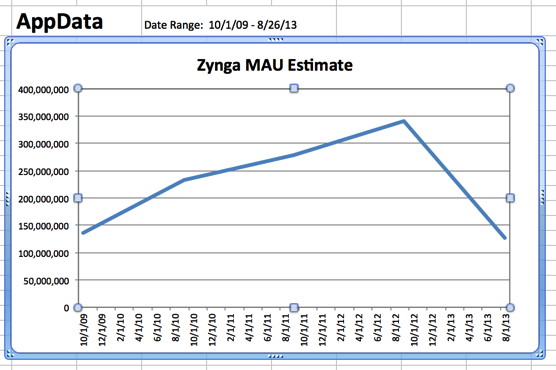

Finally, Zynga has seen a massive erosion of its user base, one that has accelerated in recent months. The industry analysis firm AppData estimates that Zynga's Monthly Average Users (MAUs) have now fallen below 127 million, the company's lowest level in four years. And in just a single quarter during 2013, the company lost more than one-quarter of its most loyal daily users.

As a result, hundreds of Zynga employees have been laid off, Pincus has been replaced as CEO, and three top executives have recently been tossed out. The new CEO, Don Mattrick, told investors on the company's most recent earnings call to expect "two to four quarters of volatility." In other words, the company has a rocky short-term future ahead of it.

AppData

In interviews with current and former Zynga employees, a picture emerges of a firm that underwent an astonishing rise but soon found itself sagging under the weight of over-management, missed opportunities, and the lack of a real long-term vision. Zynga declined to make any executives available for this story, only sending Ars a transcript of the company's most recent earnings call.

"A lot of people internally at Zynga are jaded," said Dave Dopson, a former Zynga principal engineer who is now at another major Silicon Valley company. "The whole company is very short-term minded. There must have been some artists that like drawing cutesy characters, but [to the] majority of the people, [it's like]: we found this money-printing machine; help us oil the wheels and make more money.

"Here's the real question you need to answer: once they cut all the high-expense ratio, the stuff that they do at a cost point that's so high, is there anything left? Is there still a core of things that's profitable, and how big is that company?"

“Every horrible thing in the book”Pincus rose rapidly through the venture capital and financial services world with his net worth steadily increasing at nearly every point along the way. Before reaching the age of 50, he was already listed on Forbes' list of billionaires.

After receiving his MBA from Harvard Business School in 1993, Pincus went to work for Tele-Communications, Inc., which later became AT&T Cable. Two years later he founded Freeloader, a simple way for people to publish webpages, and he sold it seven months later for $38 million. Four years later he founded his second company, Support.com, which later went public. Finally, in 2003, Pincus founded tribe.net, a short-lived social network that was originally funded by various big names in media and venture capital, including The Washington Post, Knight Ridder Digital, and the Mayfield Fund. After initial failure, Pincus bought the company back from investors, refocused it, and eventually sold it to Cisco.

Despite the successes, though, Pincus still felt like he had not yet "arrived" in Silicon Valley. "There's an A-list here, and then there's everyone else," he told The New York Times Magazine in 2005. "And I'm not A-list."

In May 2007, Facebook opened up an API in an attempt to quash MySpace and other social networks by inviting developers to build apps that would run on top of Facebook. Pincus saw an opportunity, and within two months he launched what became Zynga Poker.

"Obviously, before they opened it up, nobody really even knew what a powerful thing a Facebook app could be," Pincus told Mediabistro in 2009. "While I was doing Tribe, we realized that there would be a new arms race in new software features for social networks. The whole time I was doing Tribe, I thought that the thing I would have loved to do is games. I've always said that social networks are like a great cocktail party: You're happy at first to see your good friends, but the value of the cocktail party is in the weak ties. It's the people you wouldn't have thought of meeting; it's the friends-of-friends.

"What I thought was the ultimate thing you can do—once you bring all of your friends and their friends together—is play games," he added. "And I've always been a closet gamer, but I never have the time and can never get all of my friends together in one place. So the power of my friends already being there and connected, and then adding games, seemed like a big idea."

Pincus knew that being first with a popular Facebook game could essentially be a one-way ticket to success. He told the New York Times in January 2008 that rival game makers "will be faced with an opportunity to launch a game in the directory next to 1,300 other games and hope it gets found or to launch a game with us."

But in addition to timing its move into social gaming well, the new company also engaged in some dodgier shenanigans to drum up users. According to an e-book by VentureBeat reporter Dean Takahashi, in March 2008 Zynga added a "lead generation" mechanism where players could get in-game chips if they agreed to take part in some sort of sketchy revenue-generating deals, like accepting a sign-up offer.

As Pincus himself famously summarized it before an audience of University of California, Berkeley students in the spring of 2009, the tactics were acceptable ways to gain the control he wanted:

I knew that I wanted to control my destiny, so I knew I needed revenues right fucking now. Like, I needed revenues now. So I funded the company myself but I did every horrible thing in the book to—just to get revenues right away. I mean we gave our users poker chips if they downloaded this zwinky toolbar which was like, I don't know, I downloaded it once and couldn't get rid of it. [laughs] We did anything possible just to just get revenues so that we could grow and be a real business—so control your destiny. That was a big lesson, controlling your business. So by the time we raised money we were profitable. Investors came knocking. In 2008, Zynga received $5 million in venture capital from Union Square Ventures to fund a company of just 27 people. In 2009, another major VC firm, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, kicked in $29 million.

But Zynga didn't hit the big time until it had two smash hits, Mafia Wars (June 2008) and FarmVille (June 2009). FarmVille in particular was a runaway success. Within two months, Zynga announced that the game was gaining "more than one million new daily active users a week on average."

Making fun a scienceZ

ynga's success has often been attributed to wholesale copying of other games. Before FarmVille, there was Farm Town. And before Mafia Wars came Mob Wars. Zynga's copies are nearly identical.

"I don't fucking want innovation," an anonymous ex-employee recalls Pincus saying in 2010, according to the SF Weekly. "You're not smarter than your competitor. Just copy what they do and do it until you get their numbers."

As the local alt-weekly reported:

The former senior employee who was present for Pincus' "No innovation" diatribe described Zynga's business model this way: "Steal somebody else's game, throw millions of dollars at it, and then, if it doesn't have it already, add virtual coins." When asked if he experienced anything like Pincus' "no innovation" remark, Zynga's former general manager Erik Bethke told Ars, "Yes, too many to count."

But Zynga wasn't without innovation of its own; the company turned the getting and monetizing of users into a science.

Bethke joined Zynga in July 2009, when his company GoPets was acquired for about $1 million in cash, and "when we finished earning out options, about $5 to $10 million." He worked as director of product on the FarmVille team, when its daily active users (DAU) numbered around six million. He later moved to Mafia Wars and was eventually promoted to general manager.

"One of the things that I think treated Zynga really well is that [Mark Pincus] and [co-founder Eric Schiermeyer] had a system of weekly check-ins called 'Numbers Review' and 'Roadmap' that happened back to back," he said. "You would review your product and how much DAUs did I have yesterday, today, how much did it make? You would go deeper. What did you ship last week and the week before? How do you measure that impact? It was my job to run that meeting. So I would spend 24 hours previous to that meeting doing a bunch of analysis, doing slides, working with managers, and you'd run through it. Mark and Eric had the stamina to do a weekly touch on every product in the company. That kept things really well aligned. Management knew what each product was doing, everybody knew what the products were—the company, at the time, was only 280 employees."

And Pincus' ability to multitask was something that greatly impressed Bethke.

"[Pincus and I] were working 15 feet away for three to four months," Bethke told Ars. "He has so much energy, he can be on his phone, typing, listening to PowerPoint, and debating with another person with full intelligence to handle two separate conversations. He has a tremendous ability to process inbound information. He can debate math and metrics and can be surveying the room for body language: 'Hey: I see you frowning, what's going on?'"

But Bethke was mostly intrigued as to how Zynga could attract so many players so quickly.

"I got a turbo education on how to do the viral marketing," he said. "It's where you design features to be more social: go accomplish this with your friends. How can I make this fun, especially asynchronously, and how can I get people to invite more people? What was good and transformative about FarmVille [was that] it brought in tens of millions of adults who had never played [games] ever. It opened up casual light entertainment, and not time sensitive gaming, to 100 million people."

Anyone using Facebook around this time may remember having their wall flooded with requests from friends to help water their virtual crops or to go on virtual missions. Critics called it spam. But "a lot of people didn't mind," Bethke said. "A lot of people don't have stuff going on. And it's pretty delightful to get messages from FarmVille or Mafia Wars. It wasn't spam to the vast majority of players or it would not have worked."

Of course, that "spam mechanic" could be circumvented by spending real money for virtual goods in the game—and around three to five percent of players did so. In industry speak, this crucial moment is known as "the pinch," when companies like Zynga can extract money from its players. This is the crux of Zynga's business model: get a big number of players to play a game and get a tiny portion of that big number to pay for it.

Slade Villena, a developer on FrontierVille (released in June 2010), who worked for Zynga for eight months in 2011 and has been public about his disagreements with the company's practices, told Ars that there's an inherent tension between making games that are designed at their core to be moneymakers versus games that are designed to be fun.

"[As the company began receiving more investment], the company culture started going, 'Let's listen to our analytics and our managers, compared to what's actually happening in our game pipeline,'" Villena said. "They had selective data analysis; they were saying they were a fast-growing company. They didn't realize they were losing more customers than they were gaining new customers. The first-time user, that's like gold, man. That's gold for a game developer. This is your first experience! But they didn't take advantage of that experience."

Villena said that he and his colleagues were pushed to work constantly, frequently hitting 80- or 100-hour work weeks. Despite the hours, the games suffered.

"During my five-month mark, it started turning sour when we were pushing a lot of code that was destroying the ecosystem—they were not fixing bugs," he said. "At one time, I had 10,000 players trapped inside a quest. 10,000! The attitude was 'Don't worry about them.' [Management] would rather grab new players, keep them for three months or so, get $5 to $10 from them, and those players would quit and leave."

The FrontierVille developer said that what pushed him to quit was being told by his manager that he had to "bump up the drop rate for a certain item." That item would enable the player to complete a quest directly—but the item cost money.

"I wanted to lower the drop rate, to make it statistically possible to get this item, to keep it scarce," Villena said. "But then it started happening to every single item in FrontierVille. The main purpose of them putting [the rate] up so high was so people could spend the tokens, and the strategy for you to make a profit was to get players to spend those tokens as much as possible. You're reinforcing a negative attitude, rather than reinforcing a positive attitude so people keep playing the game."

With all that talent and all that money, Villena now says the company should have tried to invest in an entirely different game.

"[Management] could have developed one game that didn't rely on a microtransaction," Villena said. "They were playing the stock market game and the media game. It got crappy when we started analyzing players' behavior and tweaking for profit."

Jason Pyke, a former Zynga designer who worked on the never-released FarmVille 2 Mobile and Party Place, told Ars that he experienced a lot of financial pressure from project managers (PMs) within the company.

"You could always fight back, but ultimately what it came down to was: I could always argue that this would make the game fun, but I had a PM tell me—many times—that they 'couldn't get data on fun,'" said Pyke, who lost his job as part of the significant layoffs in June 2013.

Should I stay or should I go?

In addition to being beneficial for Zynga, the gaming firm's rise also helped Facebook. After all, this was around the same time that Facebook was trying to figure out how it was going to make money. In February 2010, Facebook introduced Facebook Credits, a micropayment system that could be used to buy in-game items—and Facebook took a 30 percent cut of all revenue earned through Credits. Seeing that Zynga was the hottest thing on Facebook, it was easy to see why Facebook would want its relationship with Zynga to continue.

"There were points in time where Zynga was a significant portion of Facebook's revenue," Bethke said.

But the relationship between the two companies could be rocky. Zynga's "spam mechanism," as it came to be known, only worked because its messages were given the same priority as any other Facebook message. That lasted until March 1, 2010, when Facebook changed its policy. After that, Zynga's traffic fell precipitously. FarmVille usage soon dropped by 26 percent to 61 million monthly users, according to AppData.

While Facebook's move to limit Zynga's activity was certainly public, a series of behind-the-scenes talks began. And this, Bethke says, was a key moment in Zynga's short history. The question was whether Zynga should abandon Facebook entirely and concentrate its efforts on building Zynga.com as a direct platform for players or if it should just deal with Facebook's policy tweaks and put its fate in the social network's hands. The matter was complicated because Pincus himself was an angel investor in Facebook, retaining a 0.5 percent stake in the company (now worth over $400 million).

"I felt that the company would be a lot stronger if we actually pulled back a bit from Facebook and we had to catch our own fish," Bethke said. "There's a site called Zynga.com. We could keep [games] asynchronous, but if we were on our own, that would be our own user base. We would have to respect their e-mail [privacy] really well. We would have to take care of it so much more carefully. It was hotly debated in the company. We did the errand work to run our own site. It was a project and we had a lot invested in it. It was a romantic time to prepare for that possibility. It wasn't an easy decision."

The former Zynga manager said that he was called into a meeting between Pincus and Bing Gordon, a board member at Zynga and an investor at Kleiner Perkins.

"They asked me, in my opinion, should we leave or should we stay? I was touched and moved that they thought highly enough of my opinion," Bethke said. "I told them that we're going to learn more and learn faster without [Facebook]."

But this was a tough sell. Zynga had investors to please and 1,000 employees to pay—and Facebook had so far been key to its growth.

"The company was split—this is just my impression—but most of the guys who had built their own companies and had done their own stuff, we were almost universal, let's give it a shot," Bethke said. "We're sitting on a pile of money, we have great games, we have players that love our games. If we move out, they will come with us. That will be enough to build a business around. There are others that come from career company folks. They say that it had great revenues and was going public and it seemed to them irresponsible to change that. I think both viewpoints are valid."

Zynga had gone so far as to prep FarmVille.com, a standalone Web version of the game that didn't require Facebook at all. But in May 2010, Pincus eventually concluded that Zynga would stay with Facebook, bringing the two companies back from the brink of what was dubbed "nuclear war." The two firms signed a five-year deal where Zynga would broaden its use of Facebook Credits and where Zynga would pay Facebook 30 percent on each transaction fee for an in-game purchase.

What did Zynga get? As VentureBeat reported in its 2011 e-book:

But there was another agreement the companies didn't talk about. In that deal, Facebook promised to market its platform and grow its user base so that Zynga would always have fresh users for its games. For its part, Zynga agreed to make its games exclusive to Facebook as long as Facebook delivered certain user numbers to Zynga. No other companies were able to strike a similar deal. Staying with Facebook meant that Zynga had to play by Facebook's rules, which got increasingly detailed. "So, for example, I misworded [an offer on Mafia Wars] and I got a request channel moratorium for 24 hours, and we would drop DAU by 10 to 15 percent," said Bethke. "It was up to Facebook to interpret their [Terms of Service] and to see if you violate the spirit of the letter. [There were rules about] the specific language around that pop-up, how you say it—what tense the verbs are in can get you in trouble with Facebook. That happened a lot in 2010. It didn't happen so much in 2009, because Facebook didn't care about spam."

Acquisition missionMeanwhile, as Facebook and Zynga were sorting out their differences, Zynga went on a shopping spree, acquiring 11 companies in 11 months. The acquisitions were possible thanks to huge new cash infusions. In December 2009, Zynga received $180 million from a Russian venture capital firm called DST. In 2010, Softbank, the Japanese mobile giant, kicked in $150 million to fund Zynga Japan. With that new venture capital and existing money, the company acquired Serious Business in February 2010.

Zynga picked up a Chinese game startup called XPD Media and began opening satellite offices in various cities outside its San Francisco headquarters, including Los Angeles and Bangalore. On June 3, 2010, Zynga bought Challenge Games and renamed it Zynga Austin.

"It was crazy growth; they needed to expand," Andrew Busey, the founder and CEO of Challenge Games, told Ars. "The reason they acquired us and a lot of other CEOs, they were growing so fast they couldn't get enough people in San Francisco. Building games is hard—games have to be visually compelling, sound and art integrated, they have to be fun. It's a lot harder than other software products. I think they wanted to leverage teams that could do it quickly. I don't think they were fully prepared to integrate those teams fully. I don't think they had a development strategy for how to take games to market."

Bethke, the former general manager, said that as a Zynga IPO gradually came into sight, there was tremendous pressure to have steady revenues, shake the image that Zynga had lost its mojo, and "get Zynga mobile." As Bethke sees it, the problem was that it all happened without priorities.

"[Pincus is] obviously smart or he wouldn't have achieved what he had achieved," Bethke said. "He's so intense and he's not organized in what he thinks is important. Everything is important simultaneously. I got chided by the other GMs: 'Hey Eric, you're engaging with Mark too closely. We would get done faster if you would engage less.' What would be frustrating is that it would be difficult for Mark to prioritize. Is it important to do this, that? And he would say they're all important. Do you want it on time? Cheap? Successful? Which one do you want? [He would say,] 'I want it all.'"

But by adding new studios, new titles, and new players, Zynga seemed to be concentrating on short-term gains rather than longer-term planning. It's no coincidence that 2010 was Zynga's only profitable year to date—and its most ambitious in terms of acquisitions.

Zynga began releasing many new games, both those that were developed in-house ( Treasure Isle, CityVille) and through acquisition (Words with Friends, Chess with Friends).

CityVille in particular immediately did well, surpassing FarmVille as the company's most popular game. It reached over 100 million monthly active users in just 43 days.

"[Zynga] was pioneering [social gaming]—no one had ever done it before. They were doing it the best, getting more people to play the games," Pyke, the former Zynga designer, told Ars. "They earned a crap-ton of money really, really fast. They went from being a startup to being a huge company crazy fast. Every quarterly meeting we would see a slideshow of companies we got... I feel like [it was] how child stars or pro athletes can go bankrupt: parties all the time and all of a sudden the money is gone."

The lean times came quickly. Busey, who served as the vice president and general manager of Zynga Austin from May 2010 until September 2011, said that by mid-2010 Zynga had reached a point where its traditional growth strategies were not working as they had.

"I think it was a surprise that it stopped as quickly as it stopped," he said. "There just weren't any new players. They got pretty close to saturation on Facebook. Once you have that, your growth is constrained by monetization. You can't go in and retune a game's monetization if it wasn't designed to do that.

"They were so focused on DAU versus revenue, and that hurt them," he added. "They portrayed the importance of DAU over everything else, when what really is [important] in the long-term situation is average revenue per daily active user (ARPDAU)."

Class war

Zynga continued along this trajectory throughout the rest of 2010 and into 2011, ballooning its revenues and employees and setting things up for its eventual IPO in 2011.

But that IPO was curiously constructed. It's not unusual for companies to set up different classes of shares, giving some to the public (Class A) and other more valuable shares (Class B), which typically have more voting power, to early investors and founders. Zynga took this concept a step further, giving founder and CEO Mark Pincus sole access to a rare third class of stock (Class C).

As the December 2011 Amendment to Zynga's S-1 filing makes clear, Class B shares get seven votes per share, while Class C shares get... 70 votes per share.

"Mark Pincus, our founder and Chief Executive Officer, holds shares of Class B common stock and all of the shares of Class C common stock and will control approximately 36.2 percent of the total voting power of our outstanding capital stock immediately following this offering," Zynga noted.

Further, unlike most publicly traded companies, voting power to make corporate decisions is concentrated in a relatively small number of hands. Zynga said that 98.2 percent of all voting power would lie with those who held the Class B and Class C shares. For the public, "This concentrated voting control will limit your ability to influence corporate matters and could adversely affect the market price of our Class A common stock," Zynga said.

In addition, all future sales of Class B or Class C stock would immediately convert those shares to Class A—increasing the relative voting power of each remaining Class B and Class C stockholder. Pincus, in particular, might eventually "control a majority of our total voting power," Zynga said. "Mr. Pincus is entitled to vote his shares in his own interests and may do so."

Almost instantly, Pincus solidified his status as one of Silicon Valley's elite, über-rich A-listers. Zynga's eventual IPO made Pincus a billionaire based on the company's valuation.

Pincus converted that paper money into real cash as soon as possible by selling some of his Class B shares during a secondary offering in March 2012. As the Wall Street Journal reported at the time, "If sold at Friday's closing price ($13.40), Mr. Pincus's proceeds from the sale would be about $220 million."

Within months, Pincus and other executives were hit with a lawsuit accusing them of insider trading—a case that still continues today. These days, however, Zynga is worth just $2.80 per share.

Some former employees have called into question Zynga's entire set of business practices, noting their corresponding financial ramifications.

"The impact is that you have a company that is mining a non-renewable resource [in the form of new, casual gamers] and presents itself as a growing game company, [when] in actuality that revenue capped and then declined," Dave Dopson, the former Zynga engineer told Ars. "Right after [Zynga] created that expectation, the people who were running the company managed to collect a lot of the value that they had created.

"It's brilliant. I don't have enough data to say for certain [whether it was intentional.] I do have to wonder, when you have right after the insider sales finished, and the next results came out, and the stock declined right after. They managed to sell right at that sweet spot. The difference was between [around] $12 and $3 a share. That's a factor of four."

As for Zynga itself, the company ended the 2011 year with its highest net loss to date: $404 million.

Bring in the clownsDuring the first months after the IPO, however, the stock price was rapidly rising, and the company began spending cash. Former employees tell Ars that the company spent money on trivial things like lavish food and drink but also on a top-heavy bureaucracy that made some developers working on future titles feel over-managed.

It's no secret in Silicon Valley that companies spend money on amenities for their employees as a way to sweeten their workdays. Gourmet meals, Wi-Fi-enabled shuttles, dry cleaning, child care, and many other services are well-known at large tech companies like Google, Facebook, Twitter, and others. Zynga was no exception.

A former senior game designer who wished to stay anonymous "because the games industry is so small and Zynga comprises a very large portion of my professional network" told Ars that in his early years, every time a new game launched there would be "an amazingly lavish party." For example, when Treasure Isle launched in 2010, the company went all-out.

"[Zynga] would rent out the Tonga Room [a cocktail bar in the well-heeled Nob Hill neighborhood of San Francisco], decorate it up like a tiki palace, and have a tiki party there," the designer said. "We get there and we get Treasure Isle knife kits, with flip-flops and bandannas, and they had hula dancers perform for us there."

He said that his team had an internal bet with a Zynga executive that they would not be able to make $1 million in revenue in the game's first 30 days. If they did hit the goal, the executive would take all 36 team members to The French Laundry, an extremely fancy restaurant in Yountville, California, about an hour's drive north of San Francisco, in the region's wine country. They hit the goal.

"We got hors d'oeuvres on the grass outside and full meal with wine pairing inside," he said. "So that was the start of the lavishness."

By 2012, with losses mounting, that behavior didn't seem to be abating. One current Zynga employee, who works as a principal engineer and wished to stay anonymous, told Ars that in 2011 and 2012, big parties happened every three months.

"Every quarter they had events," the engineer said. "They had one somewhere in Golden Gate Park—bouncy castles, trucks and restaurants, and free alcohol. They probably spent hundreds of thousands of dollars. [They were] just blowing money left and right. Even during the [weekly] happy hours they would custom-print [vinyl] banners. It was just flaunting money for no purpose."

Former and current Zynga employees even told Ars that at one point in early 2012, Pincus hired clowns to perform in the Zynga office as a way to create a "fun environment" for his game company.

"I came in one day and there were clowns that were passing out balloons," said the current Zynga principal engineer. "Some people said they were deathly afraid of clowns! I don't know the thought process there. [I mean, why not] jugglers? Nobody is afraid of jugglers."

ManagementMore importantly than the cash outlays, the company was beefing up its middle management. With so many project managers, division heads, and vice presidents, 2012 seemed to be a time when Zynga couldn't quite figure out what to do next.

"We always had long-term direction; unfortunately, our long-term direction would have to change every three to six weeks," Tucker Dewitt, a former Service Reliability Engineering (SRE) manager at Zynga, told Ars.

Jason Pyke, the former Zynga designer, described his experience of working on Party Place. He said the game went through a "15-month production cycle" and didn't launch until December 2012.

"That went through development hell. We had a lot of people above us reviewing it and giving feedback, but they would give contradictory feedback, or they didn't play it much and they would just have a reaction to it," he said. "It didn't always make sense, and you would have to do it. Sometimes [upper managers] would all discuss after we [the developers] left [the meeting.] Sometimes we'd be like 'We nailed it!', and we'd get an e-mail saying that they didn't like it as much as they actually said. That was what was continually extending the project. We had our design in place, and someone would sign off on it, and three months later [that person] wasn't even in the division. There was no unified vision at the top. People would come and go and leave their footprint and not see it through."

That was far different from Pyke's previous experience at Page 44 Studios, which Zynga quietly acquired in September 2011.

"At Page 44 our way of working back then was we would always hit our deadline, and that was our mantra of why we were successful," he said. "If you need a game by July 7, we would get it done. We might have to cut some stuff out, but we would get it done."

Pyke also said that newer and lesser-known projects would often play second fiddle to the flagship games, like FarmVille, CityVille, and Mafia Wars, which got "more quality assurance and bigger budgets."

"A game like mine you would get one to two designers, three artists, and half a dozen engineers," he added. "A bigger game could have double that or more."

In fact, the entire concept behind the game changed radically toward the end of 2012, just months before it was to launch.

"We had one VP who got hooked on this idea that we would have bonus features where you could throw parties, and you could have friends over," Pyke said. "I likened it to the invincibility star in Super Mario Bros.—it's unlimited time!—and then the party is over and you have to build up. [Management] liked it [so much] that they changed it to build around it. Everything had to be social. They wanted additional features. 'The party [concept] sounds awesome, let's make this around parties.' The game is almost done—now [parties] are the center point. At that point, we'd been in development for over a year. All the assets that were made for it weren't developed to be a party game. You could buy folded towels in our game, [but] why would you want that in a party game?"

And even for a short-lived title like Party Place, there was what Pyke called a "surplus of employees." Rather than give a nimble core team an assignment that could be done quickly, a team would often be over-saturated with employees and outside consultants.

"[One day we would be told] 'This is your team and you get X number of people on it'—that was something that they didn't do before," he said. "You need another PM, you get another. Sometimes you don't even need them, we would just get them. 'OK, I'll find something for them to do.' There were people who were pro game consultants. We had one guy who would come and would fly out from Boston and sit in on various games and would say, 'Here are my ideas.'"

As 2012 continued, the results of this process played themselves out. Zynga had been putting out one forgettable title after another for months—without any runaway successes à la CityVille, FarmVille, or Mafia Wars. The stock price went on a nonstop downward spiral, falling 70 percent in the eight months since the company's IPO in December 2011. Worse still, five high-level managers left the company in August 2012, including the manager of CityVille, Zynga General Manager Erik Bethke, and the company's Chief Operating Officer, John Schappert.

A new visionIn October 2012, Zynga announced a write-down of $85 million to $95 million on the value of OMGPOP, makers of Draw Something—more than half of what the company paid for the studio just months before. (OMGPOP was completely shuttered by June 2013.) The company ended 2012 with its second-highest net loss in its short history, over $209 million.

The company was looking for new directions, and in December 2012, Zynga filed a "preliminary finding of suitability" with the Nevada Gaming Control Board, the first step toward offering real-money gambling in the US.

"These are all steps that are moving us toward our long-term vision in real money games," the company's COO, David Ko, told investors a few months later.

As 2013 began, Zynga seemed determined to turn things around, largely by cutting costs. In February 2013, it shuttered satellite offices in Baltimore, New York, and Texas. It launched real-money gaming in the United Kingdom two months later—only to shut it down by July 2013. That was the same month that founder and CEO Mark Pincus stepped down as chief executive, replaced by Don Mattrick, a longtime Microsoft veteran.

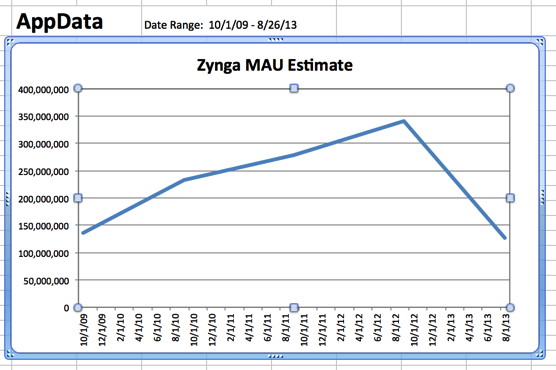

In its Q2 2013 earnings statement filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Zynga reported that the number of daily average users (DAU) dropped to 39 million in the second quarter of 2013—the lowest ever since the company began keeping track. In the first quarter of 2013, the DAU fell to the then-lowest record, 52 million users. The fall to 39 million means that 25 percent of its daily user base stopped using Zynga products in just one quarter. By mid-August, new CEO Mattrick fired three top executives.

AppData

What's next for Zynga? In business, of course, there's no clear strategy for success, but nearly everyone that we interviewed for this story agreed that Zynga needs to trim the size of its staff. It needs to pare down its stable of titles, try out more new games, and kill them sooner based on more realistic metrics that affect most players—not just its "whales" who are playing almost constantly. (When Zynga tests new features, it typically runs the tests for a couple of days at a time, meaning only those who are playing most frequently influence that decision.) More so than anything else, Zynga needs to fire up its mobile division, where it has struggled for years and where the most growth opportunities now exist.

"They need to try more games and kill more early, they need to run it like a portfolio rather than a bunch of separate businesses," said another anonymous former Zynga employee. "Their kill rate is 40 percent, and I would want it to be 80 percent, or at least over half. A lot of games just aren't that fun. Don't spend all the money to make them. The earliest phases are the cheapest, do a lot of that and kill stuff early. They need to run like a resource portfolio. I think Zynga has been unnecessarily optimistic and too unfocused. They have a lot of great people, but they need to get out of their own way."

Industry and financial analysts agree.

"[Zynga should] pick the areas where they want to grow and spend money in a focused way—I think that Pincus was incapable of that," Michael Pachter, an analyst with Wedbush Securities, told Ars. "I can't imagine what 3,000 employees did there. They're down to 2,300. They need to be down to 1,000. They can't afford to have 1,500 people working on new projects. Don will run the company like a business. He may figure out how to get the right cost structure."

Pachter pointed out that while Zynga was effectively burning cash left and right, its competitors were eating its lunch, particularly on mobile games. Temple Run, Clash of the Clans, and Candy Crush, some recent top titles not made by Zynga, were likely made for far less money than Zynga would have spent.

But for Zynga to succeed on mobile, it needs a new strategy that doesn't rely on Facebook users interacting with their friends.

"The social stuff, reaching out to your friends—things like social gating so you can't get past Level 7 unless you get three friends to give you a chicken egg—you can't do that on mobile as much because only one-third of people will sign up through Facebook," said Pyke, the former Zynga designer.

Brian Blau, an analyst with Gartner Research, said that Zynga might consider looking for inspiration at smaller game studios, ones that Zynga used to target for acquisition.

"[ King Games of London has] very, very small teams, and they have 10 or 15 of these at a time," he told Ars. "They will pilot these games, and they'll find the formula for the game that works, and they'll watch it grow and will promote that, and they'll do that once a year or two. And it seems to be a profitable model. They're only 500 or 700 people."

Just like Angry Birds brought Rovio back from game studio obscurity, Zynga could rocket ahead with one or two big titles.

"I think Wall Street would be happy if Zynga greatly reduced the amount of burn that they have—meaning, expenditures—but if they had games that people like, I think Wall Street would give them a break," Blau added.

The current anonymous Zynga principal engineer agreed with all these sentiments—particularly what he deemed would be more necessary layoffs.

"If they can figure that out, I think Zynga will be fine, given the trajectory," he said. "[Those are] things that Mattrick has said, and if he keeps on the right path, there's no reason the company can't be successful. It's not [the economy or any rival game company] that's destroying Zynga; Zynga is destroying Zynga. Last week, I would have said I was despondent, but now, after the [ June and August 2013] layoffs, I would say I'm cautiously optimistic."

arstechnica.com |