| | | Why the Economic Fates of America’s Cities DivergedPlaces like St. Louis and New York City were once similarly prosperous. Then, 30 years ago, the United States turned its back on the policies that had been encouraging parity.

Despite all the attention focused these days on the fortunes of the “1 percent,” debates over inequality still tend to ignore one of its most politically destabilizing and economically destructive forms. This is the growing, and historically unprecedented, economic divide that has emerged in recent decades among the different regions of the United States.

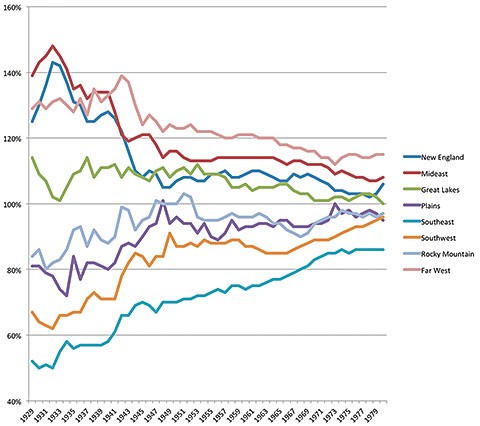

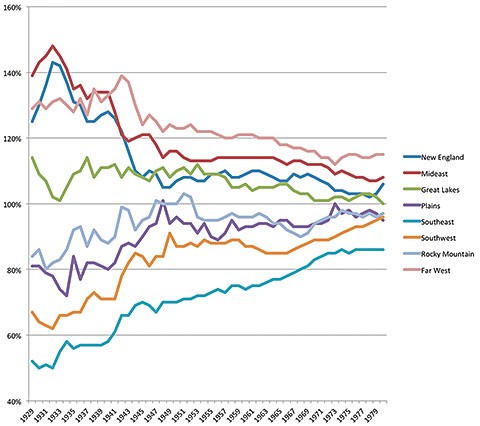

Until the early 1980s, a long-running feature of American history was the gradual convergence of income across regions. The trend goes back to at least the 1840s, but grew particularly strong during the middle decades of the 20th century. This was, in part, a result of the South catching up with the North in its economic development. As late as 1940, per-capita income in Mississippi, for example, was still less than one-quarter that of Connecticut. Over the next 40 years, Mississippians saw their incomes rise much faster than did residents of Connecticut, until by 1980 the gap in income had shrunk to 58 percent.

Yet the decline in regional equality wasn’t just about the rise of the “New South.” It also reflected the rising standard of living across the Midwest and Mountain West—or the vast territory now known dismissively in some quarters as “flyover states.” In 1966, the average per-capita income of greater Cedar Rapids, Iowa, was only $87 less than that of New York City and its suburbs. Ranked among the country’s top 25 richest metro areas in the mid-1960s were Rockford, Illinois; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Ann Arbor, Michigan; Des Moines, Iowa; and Cleveland, Ohio.

During this period, to be sure, many specific metro areas saw increases in local inequality, as many working- and middle-class families, as well as businesses, fled inner-city neighborhoods for fast-expanding suburbs. Yet in their standards of living, metro regions as a whole, along with states as a whole, were growing much more similar. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 1940, Missourians earned only 62 percent as much as Californians; by 1980 they earned 80 percent as much. In 1969, per capita income in the St. Louis metro area was 83 percent as high as in the New York metro area; it would rise to 90 percent by the end of the 1970s.

MORE FROM OUR PARTNERS  Rethinking the Think Tank Why Denver, Nashville, and Boston Are Booming Confessions of a Paywall JournalistThe rise of the broad American middle class in that era was largely a story of incomes converging across regions to the point that people commonly and appropriately spoke of a single American standard of living. This regional convergence of income was also a major reason why national measures of income inequality dropped sharply during this period. All told, according to the Harvard economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, approximately 30 percent of the increase in hourly-wage equality that occurred in the United States between 1940 and 1980 was the result of the convergence in wage income among the different states. Rethinking the Think Tank Why Denver, Nashville, and Boston Are Booming Confessions of a Paywall JournalistThe rise of the broad American middle class in that era was largely a story of incomes converging across regions to the point that people commonly and appropriately spoke of a single American standard of living. This regional convergence of income was also a major reason why national measures of income inequality dropped sharply during this period. All told, according to the Harvard economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag, approximately 30 percent of the increase in hourly-wage equality that occurred in the United States between 1940 and 1980 was the result of the convergence in wage income among the different states.

In 1969, per capita income in the St. Louis metro area was 83 percent as high as in the New York metro area; it would rise to 90 percent by the 1970s.Few forecasters expected this trend to reverse, since it seemed consistent with the well-established direction of both the economy and technology. With the growth of the service sector, it seemed reasonable to expect that a region’s geographical features, such as its proximity to natural resources and navigable waters, would matter less and less to how well or how poorly it performed economically. Similarly, many observers presumed that the Internet and other digital technologies would be inherently decentralizing in their economic effects. Not only was it possible to write code just as easily in a treehouse in Oregon as in an office building in a major city, but the information revolution would also make it much easier to conduct any kind of business from anywhere. Futurists proclaimed “the death of distance.”

Yet starting in the early 1980s, the long trend toward regional equality abruptly switched. Since then, geography has come roaring back as a determinant of economic fortune, as a few elite cities have surged ahead of the rest of the country in their wealth and income. In 1980, the per-capita income of Washington, D.C., was 29 percent above the average for Americans as a whole; by 2013 it had risen to 68 percent above. In the San Francisco Bay area, the rise was from 50 percent above to 88 percent. Meanwhile, per-capita income in New York City soared from 80 percent above the national average in 1980 to 172 percent above in 2013.

Adding to the anomaly is a historic reversal in the patterns of migration within the United States. Throughout almost all of the nation’s history, Americans tended to move from places where wages were lower to places where wages were higher. Horace Greeley’s advice to “Go West, young man” finds validation, for example, in historical data showing that per-capita income was higher in America’s emerging frontier cities, such as Chicago in the 1850s or Denver in 1880s, than back east.

But over the last generation this trend, too, has reversed. Since 1980, the states and metro areas with the highest and fastest-growing per capita incomes have generally seen hardly, if any, net domestic in-migration, and in many notable examples have seen more people move away to other parts of the country than move in. Today, the preponderance of domestic migration is from areas with high and rapidly growing incomes to relatively poorer areas where incomes are growing at a slower pace, if at all.

What accounts for these anomalous and unpredicted trends? The first explanation many people cite is the decline of the Rust Belt, and certainly that played a role. According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in 1978, per capita income in metro Detroit was virtually identical to that in the metro New York area. Today, metro New York’s per-capita income is 38 percent higher than metro Detroit’s. But deindustrialization doesn’t explain why even in the Sunbelt, where many manufacturing jobs have relocated from the North, and where population and local GDP have boomed since the 1970s, per-capita income continues to fall farther and farther behind that of America’s elite coastal cities.

The Atlanta metro area is a notable example of a “thriving” place where per capita income has nonetheless fallen farther and farther behind that of cities like Washington, New York, and San Francisco. So is metro Houston. Per-capita income in metro Houston was 1 percent above metro New York’s in 1980. But despite the so-called “Texas miracle,” Houston’s per-capita income fell to 15 percent below New York’s by 2011 and even at the height of the oil boom in 2013 remained at 12 percent below. It’s largely the same story in the Mountain West, including in some of its most “booming” cities. Metro Salt Lake City, for example, has seen its per capita income fall well behind that of New York since 2001.

The Emergence of a Single American Standard of Living: Regional Per Capita Income as a Percentage of the National Average Washington MonthlyAnother conventional explanation is that the decline of Heartland cities reflects the growing importance of high-end services and rarified consumption. The theory goes that members of the so-called creative class—professionals in varied fields, such as science, engineering, technology, the arts and media, health care, and finance—want to live in areas that offer upscale amenities, and cities such as St. Louis or Cleveland just don’t have them. Washington MonthlyAnother conventional explanation is that the decline of Heartland cities reflects the growing importance of high-end services and rarified consumption. The theory goes that members of the so-called creative class—professionals in varied fields, such as science, engineering, technology, the arts and media, health care, and finance—want to live in areas that offer upscale amenities, and cities such as St. Louis or Cleveland just don’t have them.

But this explanation also only goes so far. Into the 1970s, anyone who wanted to shop at Barnes & Noble or Saks Fifth Avenue had to go to Manhattan. Anyone who wanted to read The New York Times had to live in New York City or its close-in suburbs. Generally, high-end goods and services—ranging from imported cars and stereos to gourmet coffee, fresh seafood, designer clothes, and ethnic cuisine—could be found in only a few elite quarters of a few elite cities. But today, these items are available in suburban malls across the country, and many can be delivered by Amazon overnight. Shopping is less and less of a reason to live in a place like Manhattan, let alone Seattle.

Another explanation for the increase in regional inequality is that it reflects the growing demand for “innovation.” A prominent example of this line of thinking comes from the Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti, whose 2012 book, The New Geography of Jobs, explains the increase in regional inequality as the result of two new supposed mega-trends: markets offering far higher rewards to “innovation,” and innovative people increasingly needing and preferring each other’s company.

“Being around smart people makes us smarter and more innovative,” notes Moretti. “Thus, once a city attracts some innovative workers and innovative companies, its economy changes in ways that make it even more attractive to other innovators. In the end, this is what is causing the Great Divergence among American communities, as some cities experience an increasing concentration of good jobs, talent, and investment, and others are in free fall.”

Yet while it is certainly true that innovative people often need and value each other’s company, it is not at all clear why this would be any more true today than it has always been. Indeed, programmers working on the same project often are not even in the same time zone. The same digital technology similarly allows most academics to spend more time emailing and Skyping with colleagues around the planet than they do meeting in person with colleagues on the same campus. Major media, publishing, advertising, and public-relations firms are more concentrated in New York than ever, but there is no purely technological reason why this is necessary. If anything, digital technology should be dispersing innovators and members of the creative class, just as futurists in the 1970s predicted it would.

Per-capita income in New York City soared from 80 percent above the national average in 1980 to 172 percent above in 2013.What, then, is the missing piece? A major factor that has not received sufficient attention is the role of public policy. Throughout most of the country’s history, American government at all levels has pursued policies designed to preserve local control of businesses and to check the tendency of a few dominant cities to monopolize power over the rest of the country. These efforts moved to the federal level beginning in the late 19th century and reached a climax of enforcement in the 1960s and ’70s. Yet starting shortly thereafter, each of these policy levers were flipped, one after the other, in the opposite direction, usually in the guise of “deregulation.” Understanding this history, largely forgotten today, is essential to turning the problem of inequality around.

Starting with the country’s founding, government policy worked to ensure that specific towns, cities, and regions would not gain an unwarranted competitive advantage. The very structure of the U.S. Senate reflects a compromise among the Founders meant to balance the power of densely and sparsely populated states. Similarly, the Founders, understanding that private enterprise would not by itself provide broadly distributed postal service (because of the high cost of delivering mail to smaller towns and far-flung cities), wrote into the Constitution that a government monopoly would take on the challenge of providing the necessary cross-subsidization.

Throughout most of the 19th century and much of the 20th, generations of Americans similarly struggled with how to keep railroads from engaging in price discrimination against specific areas or otherwise favoring one town or region over another. Many states set up their own bureaucracies to regulate railroad fares—“to the end,” as the head of the Texas Railroad Commission put it, “that our producers, manufacturers, and merchants may be placed on an equal footing with their rivals in other states.” In 1887, the federal government took over the task of regulating railroad rates with the creation of the Interstate Commerce Commission. Railroads came to be regulated much as telegraph, telephone, and power companies would be—as natural monopolies that were allowed to remain in private hands and earn a profit, but only if they did not engage in pricing or service patterns that would add significantly to the competitive advantage of some regions over others.

continue reading

theatlantic.com |

|

Washington MonthlyAnother conventional explanation is that the decline of Heartland cities reflects the growing importance of high-end services and rarified consumption. The theory goes that members of the so-called creative class—professionals in varied fields, such as science, engineering, technology, the arts and media, health care, and finance—want to live in areas that offer upscale amenities, and cities such as St. Louis or Cleveland just don’t have them.

Washington MonthlyAnother conventional explanation is that the decline of Heartland cities reflects the growing importance of high-end services and rarified consumption. The theory goes that members of the so-called creative class—professionals in varied fields, such as science, engineering, technology, the arts and media, health care, and finance—want to live in areas that offer upscale amenities, and cities such as St. Louis or Cleveland just don’t have them.