Not just golf properties, Russian laundered mob money has been flowing into Trump condos too for years:

............

Trump SoHo was the brainchild of two development companies—Bayrock Group LLC and the Sapir Organization—run by a pair of wealthy émigrés from the former Soviet Union who had done business with some of Russia’s richest and most notorious oligarchs. Together, their firms made Trump an offer he couldn’t refuse: The developers would finance and build Trump SoHo themselves. In return for lending his name to the project, Trump would get 18 percent of the profits—without putting up any of his own money.

One of the developers, Tamir Sapir, had followed an unlikely path to riches. After emigrating from the Soviet Union in the 1970s, he had started out driving a cab in New York City and ended up a billionaire living in Trump Tower. His big break came when he co-founded a company that sold high-tech electronics. According to the FBI, Sapir’s partner in the firm was a “member or associate” of Ivankov’s mob in Brighton Beach. No charges were ever filed, and Sapir denied having any mob ties. “It didn’t happen,” he told The New York Times.“Everything was done in the most legitimate way.”

Trump, who described Sapir as a “great friend,” bought 200 televisions from his electronics company. In 2007, he hosted the wedding of Sapir’s daughter at Mar-a-Lago, and later attended her infant son’s bris.

In 2007, Trump celebrated the launch of Trump SoHo with partners Tevfik Arif (center) and Felix Sater (right). Arif was later acquitted on charges of running a prostitution ring.Mark Von Holden/WireImage/Getty

Sapir also introduced Trump to Tevfik Arif, his partner in the Trump SoHo deal. On paper, at least, Arif was another heartwarming immigrant success story. He had graduated from the Moscow Institute of Trade and Economics and worked as a Soviet trade and commerce official for 17 years before moving to New York and founding Bayrock. Practically overnight, Arif became a wildly successful developer in Brooklyn. In 2002, after meeting Trump, he moved Bayrock’s offices to Trump Tower, where he and his staff of Russian émigrés set up shop on the twenty-fourth floor.

Trump worked closely with Bayrock on real estate ventures in Russia, Ukraine, and Poland. “Bayrock knew the investors,” he later testified. Arif “brought the people up from Moscow to meet with me.” He boasted about the deal he was getting: Arif was offering him a 20 to 25 percent cut on his overseas projects, he said, not to mention management fees. “It was almost like mass production of a car,” Trump testified.

But Bayrock and its deals quickly became mired in controversy. Forbes and other publications reported that the company was financed by a notoriously corrupt group of oligarchs known as The Trio. In 2010, Arif was arrested by Turkish prosecutors and charged with setting up a prostitution ring after he was found aboard a boat—chartered by one of The Trio—with nine young women, two of whom were 16 years old. The women reportedly refused to talk, and Arif was acquitted. According to a lawsuit filed that same year by two former Bayrock executives, Arif started the firm “backed by oligarchs and money they stole from the Russian people.” In addition, the suit alleges, Bayrock “was substantially and covertly mob-owned and operated.” The company’s real purpose, the executives claim, was to develop hugely expensive properties bearing the Trump brand—and then use the projects to launder money and evade taxes.

The lawsuit, which is ongoing, does not claim that Trump was complicit in the alleged scam. Bayrock dismissed the allegations as “legal conclusions to which no response is required.” But last year, after examining title deeds, bank records, and court documents, the Financial Times concluded that Trump SoHo had “multiple ties to an alleged international money-laundering network.” In one case, the paper reported, a former Kazakh energy minister is being sued in federal court for conspiring to “systematically loot hundreds of millions of dollars of public assets” and then purchasing three condos in Trump SoHo to launder his “ill-gotten funds.”

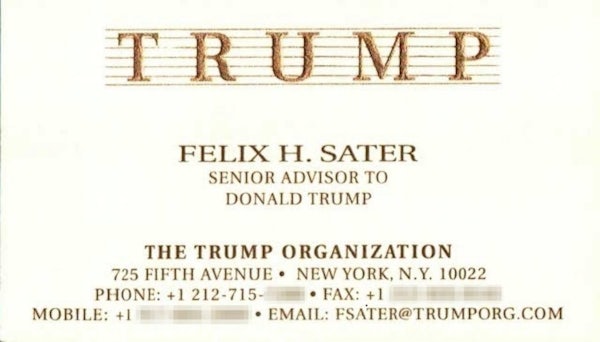

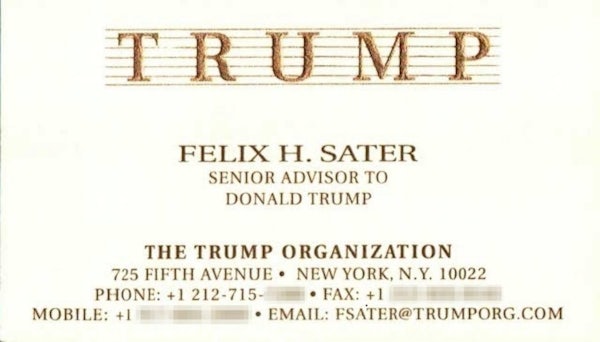

Felix Sater had a Trump business card long after his criminal past came to light. During his collaboration with Bayrock, Trump also became close to the man who ran the firm’s daily operations—a twice-convicted felon with family ties to Semion Mogilevich. In 1974, when he was eight years old, Felix Sater and his family emigrated from Moscow to Brighton Beach. According to the FBI, his father—who was convicted for extorting local restaurants, grocery stores, and a medical clinic— was a Mogilevich boss. Sater tried making it as a stockbroker, but his career came to an abrupt end in 1991, after he stabbed a Wall Street foe in the face with a broken margarita glass during a bar fight, opening wounds that required 110 stitches. (Years later, in a deposition, Trump downplayed the incident, insisting that Sater “got into a barroom fight, which a lot of people do.”) Sater lost his trading license over the attack, and served a year in prison.

In 1998, Sater pleaded guilty to racketeering—operating a “pump and dump” stock fraud in partnership with alleged Russian mobsters that bilked investors of at least $40 million. To avoid prison time, Sater turned informer. But according to the lawsuit against Bayrock, he also resumed “his old tricks.” By 2003, the suit alleges, Sater controlled the majority of Bayrock’s shares—and proceeded to use the firm to launder hundreds of millions of dollars, while skimming and extorting millions more. The suit also claims that Sater committed fraud by concealing his racketeering conviction from banks that invested hundreds of millions in Bayrock, and that he threatened “to kill anyone at the firm he thought knew of the crimes committed there and might report it.” In court, Bayrock has denied the allegations, which Sater’s attorney characterizes as “false, fabricated, and pure garbage.”

By Sater’s account, in sworn testimony, he was very tight with Trump. He flew to Colorado with him, accompanied Donald Jr. and Ivanka on a trip to Moscow at Trump’s invitation, and met with Trump’s inner circle “constantly.” In Trump Tower, he often dropped by Trump’s office to pitch business ideas—“just me and him.”

Trump seems unable to recall any of this. “Felix Sater, boy, I have to even think about it,” he told the Associated Press in 2015. Two years earlier, testifying in a video deposition, Trump took the same line. If Sater “were sitting in the room right now,” he swore under oath, “I really wouldn’t know what he looked like.” He added: “I don’t know him very well, but I don’t think he was connected to the mafia.”

Trump and his lawyers say that he was unaware of Sater’s criminal past when he signed on to do business with Bayrock. That’s plausible, since Sater’s plea deal in the stock fraud was kept secret because of his role as an informant. But even after The New York Times revealed Sater’s criminal record in 2007, he continued to use office space provided by the Trump Organization. In 2010, he was even given an official Trump Organization business card that read: FELIX H. SATER, SENIOR ADVISOR TO DONALD TRUMP.

In 2013, police burst into Unit 63A of Trump Tower and rounded up 29 suspects in a $100 million money-laundering scheme.

Sater apparently remains close to Trump’s inner circle. Earlier this year, one week before National Security Advisor Michael Flynn was fired for failing to report meetings with Russian officials, Trump’s personal attorney reportedly hand-delivered to Flynn’s office a “back-channel plan” for lifting sanctions on Russia. The co-author of the plan, according to the Times: Felix Sater.

In the end, Trump’s deals with Bayrock, like so much of his business empire, proved to be more glitter than gold. The international projects in Russia and Poland never materialized. A Trump tower being built in Fort Lauderdale ran out of money before it was completed, leaving behind a massive concrete shell. Trump SoHo ultimately had to be foreclosed and resold. But his Russian investors had left Trump with a high-profile property he could leverage. The new owners contracted with Trump to run the tower; as of April, the president and his daughter Ivanka were still listed as managers of the property. In 2015, according to the federal financial disclosure reports, Trump made $3 million from Trump SoHo.

In April 2013, a little more than two years before Trump rode the escalator to the ground floor of Trump Tower to kick off his presidential campaign, police burst into Unit 63A of the high-rise and rounded up 29 suspects in two gambling rings. The operation, which prosecutors called “the world’s largest sports book,” was run out of condos in Trump Tower—including the entire fifty-first floor of the building. In addition, unit 63A—a condo directly below one owned by Trump—served as the headquarters for a “sophisticated money-laundering scheme” that moved an estimated $100 million out of the former Soviet Union, through shell companies in Cyprus, and into investments in the United States. The entire operation, prosecutors say, was working under the protection of Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov, whom the FBI identified as a top Russian vor closely allied with Semion Mogilevich. In a single two-month stretch, according to the federal indictment, the money launderers paid Tokhtakhounov $10 million.

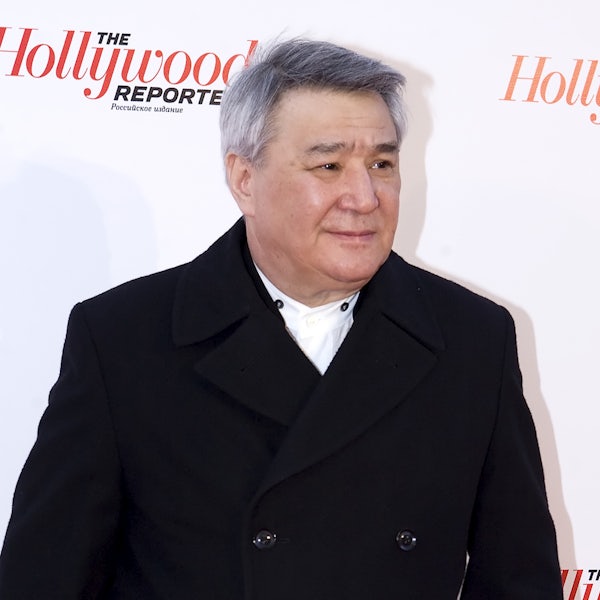

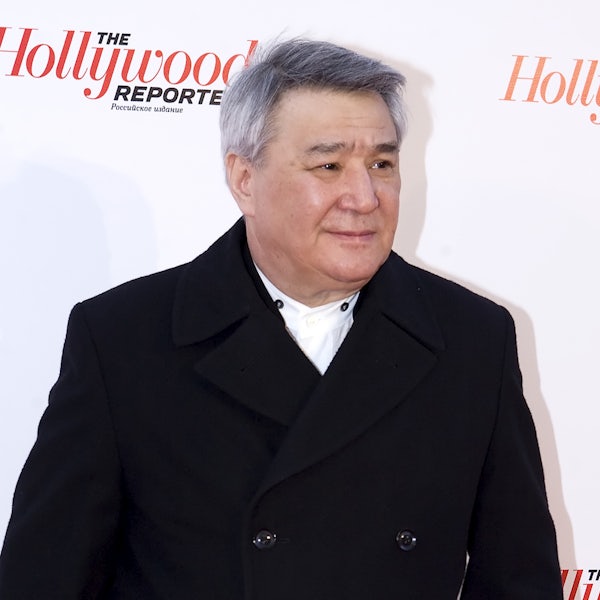

Tokhtakhounov, who had been indicted a decade earlier for conspiring to fix the ice-skating competition at the 2002 Winter Olympics, was the only suspect to elude arrest. For the next seven months, the Russian crime boss fell off the radar of Interpol, which had issued a red alert. Then, in November 2013, he suddenly appeared live on international television—sitting in the audience at the Miss Universe pageant in Moscow. Tokhtakhounov was in the VIP section, just a few seats away from the pageant owner, Donald Trump.

Alimzhan Tokhtakhounov. Dmitry Korotayev/Epsilon/Getty After the pageant, Trump bragged about all the powerful Russians who had turned out that night, just to see him. “Almost all of the oligarchs were in the room,” he told Real Estate Weekly. Contacted by Mother Jones, Tokhtakhounov insistedthat he had bought his own ticket and was not a VIP. He also denied being a mobster, telling The New York Times that he had been indicted in the gambling ring because FBI agents “misinterpreted his Russian slang” on their Trump Tower wiretaps, when he was merely placing $20,000 bets on soccer games.

Both the White House and the Trump Organization declined to respond to questions for this story. On the few occasions he has been questioned about his business entanglements with Russians, however, Trump has offered broad denials. “I tweeted out that I have no dealings with Russia,” he said at a press conference in January, when asked if Russia has any “leverage” over him, financial or otherwise. “I have no deals that could happen in Russia, because we’ve stayed away. And I have no loans with Russia. I have no loans with Russia at all.” In May, when he was interviewed by NBC’s Lester Holt, Trump seemed hard-pressed to think of a single connection he had with Russia. “I have had dealings over the years where I sold a house to a very wealthy Russian many years ago,” he said. “I had the Miss Universe pageant—which I owned for quite a while—I had it in Moscow a long time ago. But other than that, I have nothing to do with Russia.”

But even if Trump has no memory of the many deals that he and his business made with Russian investors, he certainly did not “stay away” from Russia. For decades, he and his organization have aggressively promoted his business there, seeking to entice investors and buyers for some of his most high-profile developments. Whether Trump knew it or not, Russian mobsters and corrupt oligarchs used his properties not only to launder vast sums of money from extortion, drugs, gambling, and racketeering, but even as a base of operations for their criminal activities. In the process, they propped up Trump’s business and enabled him to reinvent his image. Without the Russian mafia, it is fair to say, Donald Trump would not be president of the United States.

Semion Mogilevich, the Russian mob’s “boss of bosses,” also declined to respond to questions from the New Republic. “My ideas are not important to anybody,” Mogilevich said in a statement provided by his attorney. “Whatever I know, I am a private person.” Mogilevich, the attorney added, “has nothing to do with President Trump. He doesn’t believe that anybody associated with him lives in Trump Tower. He has no ties to America or American citizens.”

Back in 1999, the year before Trump staged his first run for president, Mogilevich gave a rare interview to the BBC. Living up to his reputation for cleverness, the mafia boss mostly joked and double-spoke his way around his criminal activities. (Q: “Why did you set up companies in the Channel Islands?” A: “The problem was that I didn’t know any other islands. When they taught us geography at school, I was sick that day.”) But when the exasperated interviewer asked, “Do you believe there is any Russian organized crime?” the “brainy don” turned half-serious.

“How can you say that there is a Russian mafia in America?” he demanded. “The word mafia, as far as I understand the word, means a criminal group that is connected with the political organs, the police and the administration. I don’t know of a single Russian in the U.S. Senate, a single Russian in the U.S. Congress, a single Russian in the U.S. government. Where are the connections with the Russians? How can there be a Russian mafia in America? Where are their connections?”

Two decades later, we finally have an answer to Mogilevich’s question.

newrepublic.com |