| | | Article about trade issues and the impact on a couple of our favorite stocks.

Link:https: //seekingalpha.com/article/4186938-china-syndrome-memory-industrys-battle-ip-theft?ifp=0&app=1

A China Syndrome - The Memory Industry's Battle With IP Theft

Jul. 12, 2018 1:45 PM ET

William Tidwell

Deep Value, Growth, contrarian, long only

Summary

Trade issues are weighing down equity values in memory industry names.

The investing community is deeply confused about the issues and the likely outcomes.

Two scenarios are examined.

The semiconductor sector as a whole and the memory sector in particular are well equipped to prosper as the "trade war" develops.

Investors who are long memory industry names like Micron ( MU), Western Digital ( WDC), and Samsung ( OTC:SSNLF) have faced any number of challenges to their core investing rationale over the course of the last six months. Despite the impressive gains over the last year and the recent reaffirmation of the strength of the argument for continuing (and even accelerating) secular growth, the industry has seen generally negative to flat stock action over the last couple of months.

Why should this be so?

In my mind, the why of the matter is easily resolved by focusing on market reaction to the almost daily headlines pertaining to trade. We need look no further than the recent news of the preliminary injunction against Micron in the UMC (NYSE: UMC) patent infringement case to confirm the suspicion. The stock has come back since that event, but there seems to be an abiding fear that the tech industry, especially semiconductors and memories, would be especially hard hit.

This fear is unfounded. Exactly the opposite is true. This article will explain why.

This problem isn't going away. The Trump administration has led with this issue politically from the very beginning and, as we approach the fall election season, isn't about to take its foot off the accelerator. What's more, substantively, the administration is certainly right to consider the ongoing Chinese theft of IP a risk to America's long-term economic viability. Whatever we might think of Trump's approach to trade - and I am highly critical of his focus on tariffs, trade deficits, and his wrong-headed and cavalier treatment of our allies - the IP theft battle is a righteous fight, and now is as good a time as any (and better than most considering the strength of the US economy and the memory industry) to fight it. So, like it or not, the battle has been joined, and where it will end is anybody's guess. Talk of an all-out "trade war" between the two most powerful nations on earth, comprising 40% of world GDP, is in the air. Damaging outcomes are potentially in play as countries, companies, and individual investors consider their next steps.

Sounds ominous, doesn't it? That's because it is. Nevertheless, we need to remember that, while this conflict certainly has the potential to be extremely damaging to the world economy and consequently to markets and equity prices, it needn't be. If we are to get to a good outcome, we need to be clear on our goals and our strategy to obtain our goals. We need to understand our opponent's motivations and objectives, strengths, and weaknesses. We need to be just as clear-eyed about our strengths and weaknesses as well. Only then, can we get to a win-win resolution of this conflict.

With the announcement today of a second list of $200B in US tariffs and China's counter with a plan to protect their affected industries, the dispute has ratcheted up to another level of intensity. How bad is this likely to get? The risk, of course, is as the cycle of measure/counter-measure becomes increasingly destructive, if we aren't very careful, we can find ourselves down the river of escalation in a place we never wanted to be. That is certainly a possibility.

But we're not there yet. So, let's figure this thing out and assess the possibilities, good and bad. As individual investors we may have no power to influence the outcome, but at least we'll be able to accurately assess how the battle is progressing and whether or not we need to take action in terms of our stock portfolio. Up to now, this algo-driven market has clearly gotten things wrong. Despite the market's negative reaction to the headlines, no damage has been inflicted on the memory industry as a whole, or on the memory sector in particular. (Author's note: when I use the term "memory", I am using that as a shorthand for the semiconductor memory and storage industry that encompasses the manufacture of DRAM and NAND.)

Are there trade actions that could adversely affect the industry? Are the US companies, - Intel ( INTC), Micron, and Western Digital - at heightened risk? Of course, but there are other actions that, while momentarily disruptive, would increase revenues and profits. If we are to know the difference, we need to evaluate some scenarios and ask some hard questions. This article is going to look at two polar scenarios in order to better understand our risks and our opportunities as this situation develops. The first will be what we will call the "war of accommodation", or as Peter Navarro, Director of the White House National Trade Council, might term it, "capitulation". In this scenario, the trade dispute is relatively quickly settled with little other than face-saving measures negotiated and no real change in China's policy. The second scenario is the "win at all costs" scenario where China is forced to completely abandon their current trade policy and essentially adopts a "free trade" strategy.

Before we get to the scenarios let's make sure we understand the problem that we need to address, what we in the tech market really care about.

It's not the trade deficit. While theoretically it would be good if it were smaller, as long as the US dollar is the international standard of exchange there are really very few adverse effects from it. What about restrictive Chinese business practices that stop US companies from entering certain segments of the Chinese economy (banking, finance) or require that US companies find majority share Chinese partners who take the lion share of the profits of the venture? This is certainly a problem, but it is not the problem. Arguably, we could sell a lot more in China if we weren't restricted from entering so many markets, but we have to remember the US isn't without some issues in this area vis-à-vis China. The two countries are fierce competitors, and that is unlikely to change. We will continue to have national security concerns about Chinese companies, and they will have the same concerns about ours. This means that restrictions on the scope and nature of Chinese participation in the US economy will continue to be a fact of life. Huawei and ZTE ( OTCPK:ZTCOF) are just a couple of recent examples. Bottom line, we should negotiate for a much more open Chinese economy for our companies but our expectations should be kept in check regarding how much is achievable in this area.

Which brings us to the real issue that is worth the fight - intellectual property [IP] protection. This one issue is so important that if we were to accomplish nothing else but resolve this one issue, we should count it a great victory for the US and indeed the whole world economy. After all, if there is one thing tech investors believe surely, it is this: the key to the 21st century is innovation. The process of digitizing our world is well underway, and as that continues, we are remaking the global economy into a new, AI-driven powerhouse that will utterly transform our lives. Beyond the base inventions, there will be a myriad of new inventions that mold the raw technology clay into products and services that will be the engine of new businesses that drive this new economy.

How could IP protection not be vital - especially to the United States, the global juggernaut of creative destruction?

IP protection is necessary and good, not only to encourage innovation but to protect the culture that innovates. Without it, the fruits of the innovators work are despoiled, and innovation, over time, stops. The beating heart of capitalism - its moral center - is the mechanism that unleashes the creativity of the human mind in pursuit of service to others. Innovation is the embodiment of that creative spirit that brings new products to market, meeting human needs and fulfilling human desires. The protection of intellectual property ensures that the entrepreneur will be rewarded for their creativity. And this reward is the linchpin of the wealth creation cycle that drives ever more innovation.

The one hopeful element in this whole trade mess is that it is on this point that the US and China share a common interest. China recognizes that it needs to protect IP. The future growth of their economy in a technology-driven future depends on it. So, there is reason for hope that this issue can be resolved, but we must be clear-eyed about the problem, the cause of the problem, and its consequences. IP protection is the key - we must never forget that. Let's take the triad in order.

The problem. The Chinese state has implemented a tactic of IP theft as the central engine of a so-called " Indigenous Innovation Policy" policy that seeks to raise the domestic content of Chinese semiconductor purchases. The specific plan was spelled out in their 2015 "Made in China 2025" document.

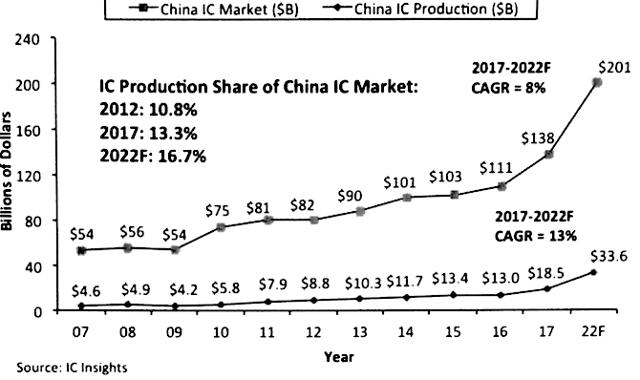

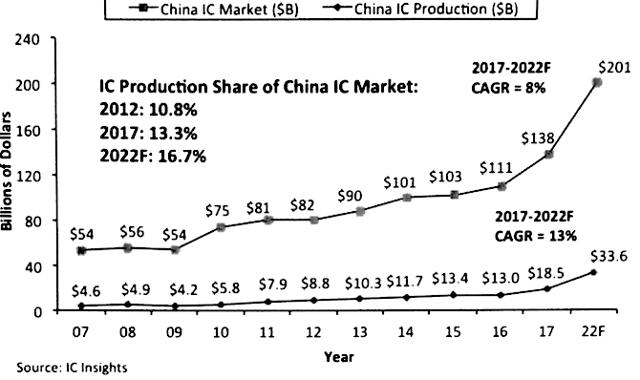

The cause(s) of the problem. Cause 1. China currently consumes almost half of the world's semiconductors but makes only 5% of them. Even counting foreign chipmaker's product, China originates less than 15% of global production of semiconductors. The Party's goal is for China, set out in the " Made in China 2025" document, is to produce enough semiconductors that 70% of China's domestic demand can be supplied by domestic producers in 2025. As the Council on Foreign Relations stated in a recent article on the "2025" initiative:

"The supply chains for hi-tech products usually span across many borders, with highly specialized components often produced in one country and modified or assembled somewhere else. Rather than abiding by the free market and rule-based trade, China is intent on subsuming the entire global hi-tech supply chain through subsidizing domestic industry and mercantilist industrial policies. Semi-official documents lay out even more specific quotas for Chinese manufacturers. Officials at China's Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) insist these targets are not official policy, though a report from the Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies argues that officials are using internal or semi-official documents to communicate targets to Chinese enterprises in order not to openly violate WTO rules.[…] Equally problematic to Beijing's goal of "self-sufficiency" and becoming a "manufacturing superpower" is how it plans to achieve it. Chinese officials know that China lags behind in critical hi-tech sectors and hence are pushing a strategy of promoting foreign acquisitions, forced technology transfer agreements, and, in many cases, commercial cyber espionage to gain cutting-edge technologies and know-how." [bold emphasis the author's]

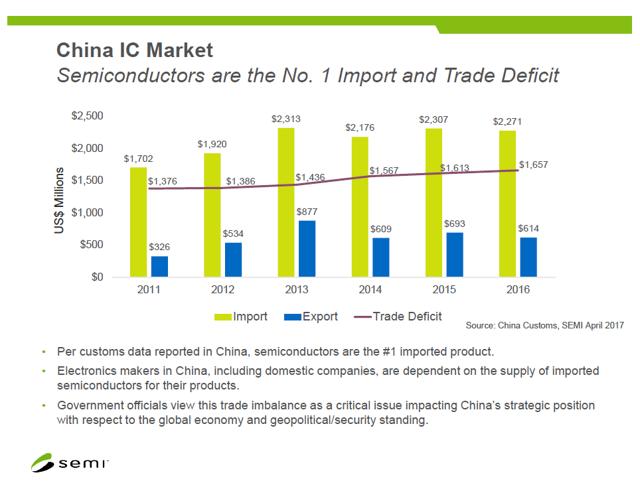

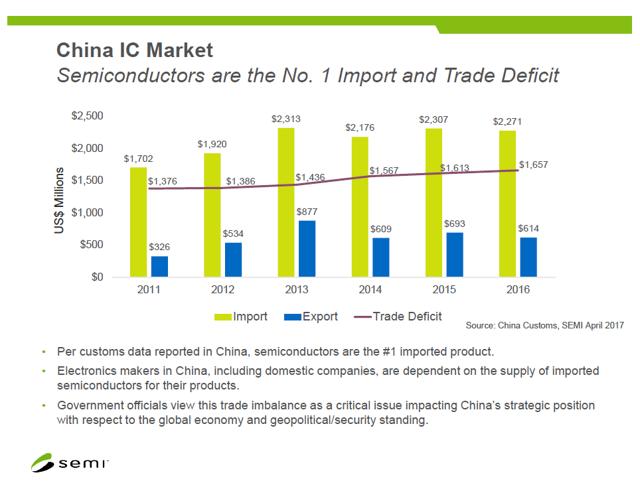

Fact is, the Chinese are almost totally dependent on foreign firms supply of semiconductors - especially memory. Here's a recent chart from the SEMI showing the Chinese position in semiconductors through 2016 with a focus on trade:

And here's an IC Insights chart that looks at Chinese IC production as a percentage of the China market:

Cause 2. Deep-seated Chinese feelings of victimization and paranoia regarding the West. Bottom line, the Chinese feel vulnerable because of their weak position in this area and do not trust the global economic system to provide them with a reliable supply. Here's a quote from a WSJ article on the recent Party campaign to celebrate Karl Marx's 200th birth anniversary:

"Decades into China's capitalism-fueled economic miracle, President Xi Jinping is promoting Karl Marx as a rallying symbol for the nation. […] For Mr. Xi, the campaign is a way to demand loyalty within the ruling party and persuade Chinese to keep faith with a Communist government that he says has employed Marx's ideas to make China prosperous and powerful. […] The propaganda is heavy on symbolism but thin on theory. Spurning discussions of capitalist exploitation and class struggle, Mr. Xi and party officials portray Marxist ideas as tools for standing up to Western imperialist bullying and restoring China's greatness."

The consequences of the problem. Focusing solely on the DRAM segment of the memory and storage industry for now, it is no exaggeration to say that the threat of the loss of IP protection is existential. China's plan to produce enough DRAM and NAND to fully supply their local market would lead to disastrous over supply in the industry, crushing prices and company balance sheets as a direct result. Because this is a subsidized State initiative, the Chinese are not concerned about the economics of their entry into the memory market. Their concern is solely based on achieving technical parity and manufacturing dominance as a foundation for attacking the entire upstream semiconductor ecosystem.

So, the critical question now is timing. How soon can China, even with the benefit of stolen IP, bring these technologies to market in significant quantity? The current consensus is China is years away from being competitive in either DRAM or NAND, with most observers who follow this topic being in the 2-5-year time frame. My view tends toward the high side. Be that as it may, one need only read a recent morning's Wall Street Journal to get a good sense of the scope of the UMC theft of DRAM technology and its potential to speed Jinhua's DRAM development. Here's the operative quotation from the article (bold emphasis the author's):

"The files Mr. Wang transferred were a grab bag of production secrets, including test procedures and results, and processes such as placing conductive layers on chips, known as metallization, Micron filings say. [Regarding metallization,] [a]nalysts say such knowledge is normally acquired via a laborious series of trial-and-error adjustments. Figuring out such a protocol would take at least three years, if not decades. In UMC's case, it took two months, according to Micron. "The Micron trade secrets that Wang stole proved invaluable to UMC's development effort and critical to the timeline of the Jinhua DRAM project," Micron said in its filing."

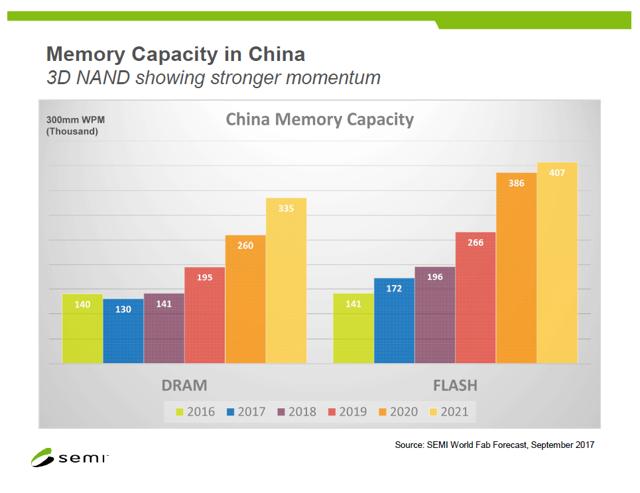

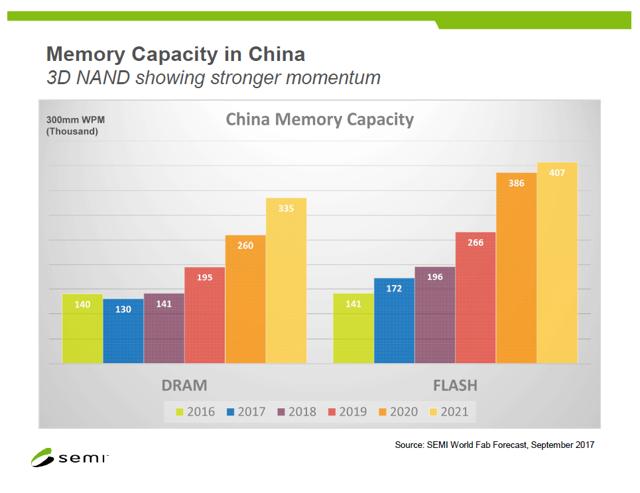

Here's another take on Chinese capability. Semi's current projection of Chinese fab capacity (expressed in thousands of wafers per month) is as follows:

As you can see from the chart above, a significant amount of DRAM and NAND is already being made in China, just not by the Chinese. Samsung, SK Hynix - DRAM, and Intel - NAND) all have fabs in China, and all have plans to expand them over time. At this time, there is no indigenous Chinese firm making competitive DRAM or NAND.

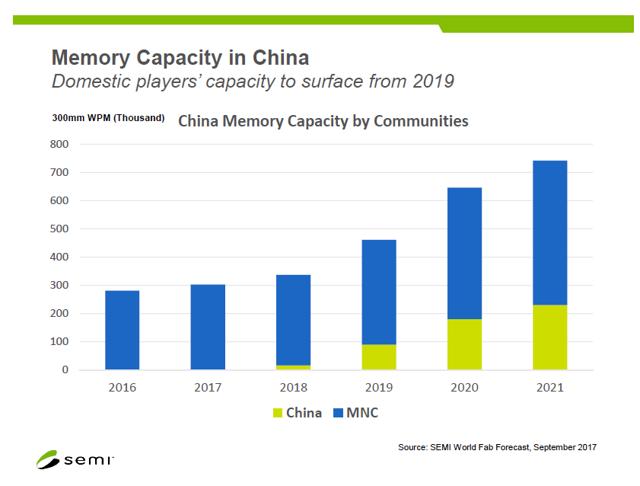

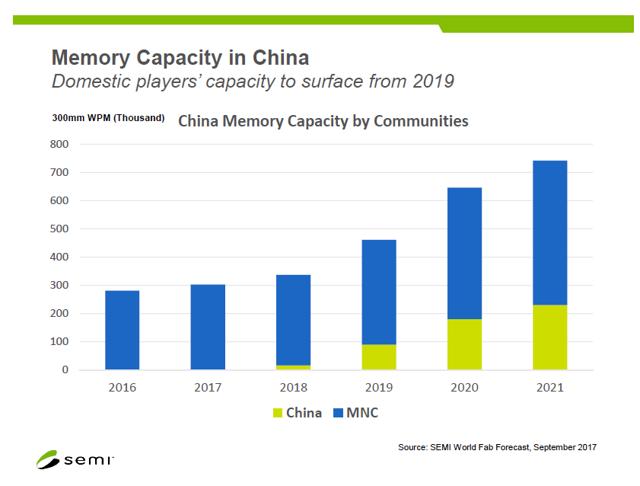

This chart from the SEMI study shows the Chinese buildup:

DRAM and NAND Wafers Combined 20212019 will see a slight ramp up in Chinese capacity, but the big increase is not projected until 2020 and 2021. And that's if all goes to plan. Even in 2021, with projections of roughly 220k wpm of Chinese capacity, China would have less than 10% of the global wafer production of DRAM and NAND. Whether that equates to a comparable share of bit output depends entirely on how successful they are in catching up with the industry's then-standard node.

To illustrate why I'm emphasizing this, let's assume that by 2021, non-Chinese producers have 1.2m wpm of DRAM capacity and 1.5m wpm of NAND. Given the current cadence of node advance, the bulk of the DRAM output in 2021 will probably be on the "1Z", or 13nm process node having an estimated bit density of .27 Gb/mm2 which equates to a wafer capacity (at 100% yields) of 2,400 GB. On the other hand, let's now assume that a Chinese producer like Jinhua is able to output 120k wpm of DRAM in 2021 on the "1X" node. This is a very generous assumption, by the way. As a recent Semiconductor Engineering article reports, Jinhua current production goal is much less ambitious:

"As a starting point, though, China's DRAM makers are developing 22nm parts. "The technology is not going to be near the leading edge," IC Insights' McClean said. "There is a market for it, but it's pretty thin."

Be that as it may, at the "1X" node the prospective 120k wpm of annual wafer output on a wafer share basis would be a 9% share of global output. Customers, however, are not interested in wafers but in bits, and because of the bit density difference between "1Z" and "1X", the average Jinhua wafer would contain only 1,670 GB, a 30% deficit to the industry's then-current "1Z" bit output/wafer. And this is most likely a best case because Jinhua's yields are likely to be much lower than the industry incumbents. Let's assume the industry's yields at 90%, and Jinhua's at 70%. The net result in that Jinhua's 9% wafer share is only a 5% global DRAM bit share, and those bits are 2 process nodes in arrears of the industry standard on a competitive basis.

So, let's now assume that our speculation about 2021 DRAM output is roughly accurate and build an economic scenario around an assumption of 5% Chinese bit share. Is that a problem for the three incumbents? No. Here's why. Let's assume an incumbent strategy of accommodation - something along the lines of we've settled our IP theft claims (more on that below), and now, we'll compete solely on a product merit basis. The likely result of such an approach would be that Jinhua is only able to sell their less capable, more expensive (about 30%) memory in China based on a China domestic content mandate basis. In other words, Chinese companies would buy Jinhua memory only because they had to.

Meanwhile, the three incumbents, having three years visibility into this process, would be gauging annual global DRAM demand growth carefully. If demand growth stays at the 20% CAGR level they are now assuming, they would bring down their own wafer growth plans to keep the world demand/supply equation in balance. The result would be roughly flat DRAM prices in 2021, an outcome that is very likely to result in strong revenue and profit growth for the companies. Obviously, if DRAM demand growth is above or below this 20% rate they would have to make other plans, but unless demand totally falls out of bed the situation is manageable.

So, that's the accommodation route. There's just one problem with that scenario, that being the ongoing active campaign of IP theft by China remains intact and unopposed. The settlement assumed in this scenario is between Micron and UMC based on Micron winning in the US, which could well involve a court order to block UMC and Jinhua DRAM sales in the United States, and even more broadly, a block on any product containing that memory. In this, "private" scenario, the US trade office in not deeply involved, and the larger US/China negotiation is basically halted with some face-saving measures taken on each side. While the industry would see expanded DRAM competition in the early 2020s, the financial impact of this competition may be limited as new memories such as 3D XPoint (and others) become a larger and larger piece of Micron and Intel's overall financial results.

Let's now turn to a tougher scenario and explore some darker terrain. Let's now assume an aggressive response by the US that seeks a full resolution to the issues that now plague US (and indeed international) trade with China. In this "win at any cost" scenario, the US demands a solution to the IP protection problem in China and seeks dramatic changes in China's most egregious trade practices. (For the purposes of this article, I won't propose a solution to the IP protection issue but ideally it would build on the TRIPS agreement that was negotiated in the Uruguay round of WTO negotiations in 1994.) What are the implications of this scenario?

First, Micron and its memory industry competitors would now become bit players and pawns in a clash between the two largest economies in the world. It is likely that such a "maximalist" approach by the US would result in the full imposition of the additional $400B of trade tariffs that Trump has threatened. The reaction of the stock market would likely be quite negative and a general sell-off would occur as the market anticipates the higher costs and reduced economic activity that would occur as a result of the tariffs. Ultimately, a full-scale trade war has the potential to result in a depressed global economy and perhaps even a US recession in 2020/21.

To the extent that global demand is depressed, memory demand would probably fall off as well - how much is hard to say, given the incredibly strong secular growth trends involving memory. (Would the hyper DCs slow their breakneck buildup of AI capabilities, for example?) For this scenario, my assumption will be that global bit demand growth will fall to zero. In other words, no growth instead of the 20% growth currently forecasted.

Initially, stock prices for memory industry names, including Micron, would undoubtedly fall, but so would the rest of the market. The overriding question for the entire global economy would become at this point: how long is this going to last?

However long it lasts, the memory companies won't be standing still. The companies will take measures that fall into three categories:

All green field CapEx would be shelved for the interim - no wafer capacity would be added.R&D on new memories and some node advances would continue, as least for the first year of the trade war, because the competitors could not afford to lose competitive momentum.The result of the two actions above is that industry wafer capacity would go down (as node advances take out wafers) and bit capacity would go up, but only in the low single-digits.The memory companies, especially the DRAM players, would lobby the US for anti-trust exemptions to allow them to craft a cooperative strategy vis-à-vis Chinese buyers. (more on this below)

Before we go on to consider further US actions (beyond the $400 B in additional tariffs) let's game plan the impact of the expanded tariffs on the Chinese and their likely response. In terms of the impact, there is no doubt that fighting a trade battle with tariff tools is a losing game for the Chinese. Their economy, after all, depends on trade much more than ours - we export only about a third as much as we import. Indeed, as of now, the Chinese market has reacted much more negatively to a prospective trade war than ours. Given the enormous debt overhang in the Chinese economy, the risk to the Yuan is significant, and that in turn directly affects the ability of the State to keep the credit spigot open for the many precariously funded state-owned enterprises. What could China do in response? Is there any area where they have meaningful leverage over the US economy?

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is no - and especially not in the tech segment - and most of all not in memory. Bottom line, China needs our technology and relies on it to provision their own upstream end product business that totals $115B in the consumer electronic sector alone, and perhaps most importantly employs hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers. China is desperately vulnerable here, as their reaction to the initial ZTE ban shows clearly.

That is why the speculation about China imposing a ban on Micron selling its product in China has been so off base. China knows full well that excluding Micron's memory chips from the China market would result in catastrophic disruption in its manufacturing base - starting with the smart phone vendors but extending to many other tech OEM segments such as communications and its internet businesses. Micron's roughly 25% share of the DRAM business is not replaceable, even if the Koreans wanted to replace it, which they don't. A moment's analysis will make it clear why.

For one thing, Samsung and SK Hynix will not want to take business from a non-Chinese customer to supply it to a Chinese company that may or may not be their customer after the trade war is settled. Second, by not shifting product from a current customer to the Chinese market both companies will have free rein to charge a considerably higher price to the desperate Chinese OEMs that need memory to meet their sales plan. Third, even if they were afflicted by some incomprehensible altruistic impulse, it is highly likely that the US and Korean governments would have negotiated an agreement that ensures that Samsung and SKH do not undertake any extraordinary supply actions. (This is the temporary easing of anti-trust laws that was referred to above in point 4.) Would the Koreans build more capacity to serve the Chinese market? No. Such a move would be clearly counterproductive because after the dispute was settled that capacity would be in excess of market requirements and prices would drop disastrously.

No, China will not ban the import of US-flagged memory, so let's put that aside and think about where their real leverage over the US resides. To the extent that they have any, it is in the area of the marquee US names that depend on China for a big percentage of their revenue - Apple (NASDAQ: AAPL), Boeing (NYSE: BA), GM (NYSE: GM), Ford (NYSE: F), Caterpillar (NYSE: CAT), KFC, Starbucks (NASDAQ: SBUX), to name just a few. It surely could inflict notable damage to the revenues and profits of these firms, but even here not without absorbing a lot of self-inflicted pain. Apple employs hundreds of thousands (indirectly through Foxconn), and the other large US brands employ many Chinese as well. Even with Boeing, would Chinese want to completely give up negotiating leverage to Airbus?

The bottom line is that China is in a weak position to fight a multi-dimensional trade war with the US. Will it get this bad? Will the Trump administration risk its political base over a protracted trade battle with higher costs and company disruptions rippling through our economy? I hope so, because with the support of the American people, the administration will be able to convince the Chinese that comprehensive trade reform is good for them as well.

The point of this exploration of this incredibly risky and negative scenario is that, however long it takes to be resolved, the memory industry will come through this battle in excellent shape as long as the IP protection issues are resolved. Would a trade war with China on this level persist through the 2020 presidential election? If so, Micron's FY '20 results could see a negative impact. FY '19, on the other hand, would still be an excellent year, unless the Trump administration, in an effort to apply maximum pressure on the Chinese, took the following two actions over the course of the next year:

Ban the sale of all semiconductor equipment to China. (Given that much of the segment is comprised of US, Japanese, and other ally's companies there is good reason to believe that the Administration has the clout to accomplish this.)Ban the sale of Micron's memory products into China. (This would be done only with the full cooperation of the Korean government who would restrain supply from Samsung and SK Hynix as well.)

These two actions, because they are so extreme, could bring the Chinese to the table, thereby driving a relatively speedy resolution to the dispute. They could also push China into an even more extreme position and motivate the regime to take extra-legal actions such as military action directed at Taiwan, or possibly the seizure of non-Chinese assets in China. This latter action would directly affect Intel's NAND fab at Dalian, Samsung's Xian NAND and DRAM fab, and SK Hynix's DRAM fab at Wuxi. In addition, TMC has a foundry in Shanghai and Micron has a back-end packaging and test facility in Xian. All could be at risk if the US/China conflict went too far.

Enough of the speculation. The abundant opportunities and excruciating risks of this issue should be obvious by now. We are in uncharted waters here. The world has never dealt with a trade dispute in an era where "free" trade and technology have combined to produce such intricately integrated supply chains. Historical antecedents are not useful in assessing possible outcomes. Hawley-Smoot is not an analogue in a world where Apple, the world's largest and most profitable company, is the finest fruit of the current system. Nevertheless, let us take from this thought exercise what we can.

I believe the lessons are:

An "accommodation" scenario is the best case in the short term for the memory industry and the worst case in the long term (2025 and beyond).The "win at any cost" scenario is the worst case in the short term and the best case in the long term, but only if wise heads can craft a face-saving resolution for China.Even in the worst case (this excludes WWIII), the memory industry is in excellent position to survive and prosper over the longer term and is in an arguably better position than other US companies with significant Chinese exposure.The only scenario that would severely impact Micron would be a US ban on China sales and that action is so extreme that the risk to equity values across all stocks would be just as big. The company would survive and would be even stronger after the trade war resolution.

In closing, there is no doubt that the current Micron stock price (closing today well up at $55.74, has the market's trade war risk assessment incorporated into it. It is up since the trade tariffs were announced and has bounced back from the Chinese court's injunction. This is entirely appropriate for a company that will have another blow-out quarter to close its fiscal year 2018 and will likely see another record performance next year.

I choose to think that political realities at home and abroad will force a solution somewhere in the middle of the two extremes posited above. WWIII or a severe global depression is not the end point. Assuming that is true, investors in memory industry and more broadly in tech as a whole will continue to do very well. Long Micron, WDC, NVDA and assessing taking a long position in Samsung and SK Hynix.

Disclosure: I am/we are long MU, WDC, NVDA, PSTG. |

|