More tRump LOSING: Stocks Are Telling Trump He Made a Big Mistake

The timing of the announcement of new tariffs on Chinese goods is hard to explain unless the Fed was a factor.

By John Authers

August 1, 2019, 9:01 PM MST

bloomberg.com

To cut rates, first raise tariffs.Tell people what to do in order to get what they want, and they will probably do it. That appears to be a key takeaway after two days of market drama.

On Wednesday, the Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell made clear that the central bank’s reaction function was changing. Rather than looking at the labor market, the main reason it cut interest rates by a quarter of a percentage point was “the implications of global developments for the economic outlook.” Further questioning made clear that he was talking about the trade situation and the risk of a worsening conflict. Meanwhile, President Donald Trump tweeted that he was disappointed that the Fed had not been more aggressive.

On Thursday came the news, in another presidential tweet, that there will be a 10% tariff on $300 billion worth of Chinese imports to the U.S. as of Sept. 1. The market reaction was dramatic. Stocks and commodities – particularly oil – tumbled on the negative implications for economic growth. And the cash and U.S. Treasury markets signaled their greatest certainty yet that the Fed will be lowering rates again next month.

When the Fed’s reaction function is led by measures of inflation and employment, neither of which the president can control (even if policies can affect them), then there is little Trump can do to force the central bank’s hand. But when the Fed is driven by “global developments” over trade, then he can very directly engineer a cut in rates by threatening new tariffs on key trading partners.

Is Trump really that cynical? We cannot know, but the timing of the announcement, when the official word was that talks with China were proceeding well, is hard to explain unless the Fed was a factor. And we now discover that the Fed is left haplessly in the role played by the European Central Bank during the sovereign debt crisis earlier this decade, or the Bank of England in the Brexit imbroglio, in that it has no choice but to offer insurance in the case that politicians do something really stupid that severely damages the economy. Central banks in this way become direct purveyors of moral hazard, and there is nothing they can do about it.

The market reaction also suggests something very strange about the latest escalation in trade tensions. Trade had steadily become less salient over the last few months. Investors thought they had their arms around the problem, but this latest tweet had a dramatic and galvanizing effect. Arguably the most visible impact came in the bond market, where the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S Treasury note dropped to its lowest since Trump was elected in November 2016:

That was quite a reversal. Meanwhile, the news amplified the trend towards a flatter or even inverted yield curve, which is generally regarded as a recession indicator, or at least as an indicator that the Fed will soon be obliged to cut rates. This is what happened to the gap between the 3-month and 10-year Treasury yields, which have been flashing a warning sign for months:

Such moves are plainly driven in part by the negative implications of higher tariffs on economic growth. But it looks as though they were driven more directly by changing expectations of the Fed. The chance of a cut at next month’s FOMC meeting rose from 64% to 92%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. By December’s meeting, the odds of at least two more rate cuts from here rose from 42% to 75%. Whether or not this was Trump’s intention, the president transformed perceptions of the likely response from the Fed.

Is this a work of a stable genius? The argument in favor would hold that Trump now gets interest rates to stimulate the economy through to the elections in 2020, while also beefing up his evidently genuine desire to take the trade fight to China. Against this, there is the argument that if he really pushes ahead with higher tariffs, the result will be lower equilibrium rates needed to keep the economy growing. Lower rates will not in fact stimulate economic activity. And there is also the matter that stock markets did not respond to the good news of likely lower rates in future, but to the shocking bad news that the risk of an all-out trade war had greatly increased. Trump takes the stock market seriously, and it seems to be telling him he is making a mistake.

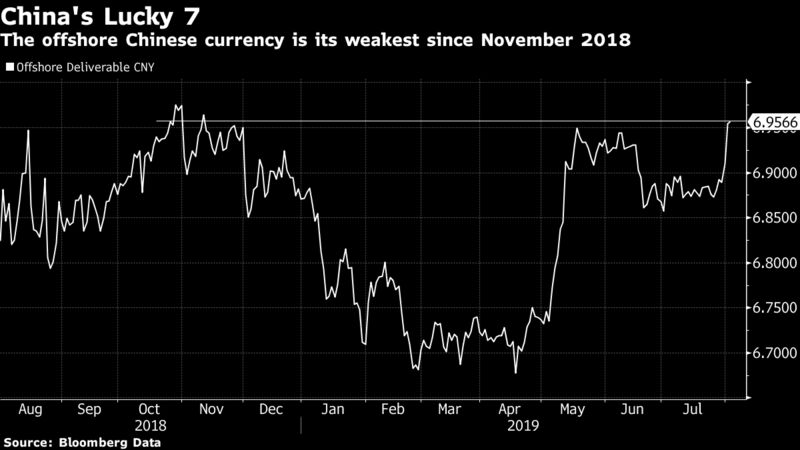

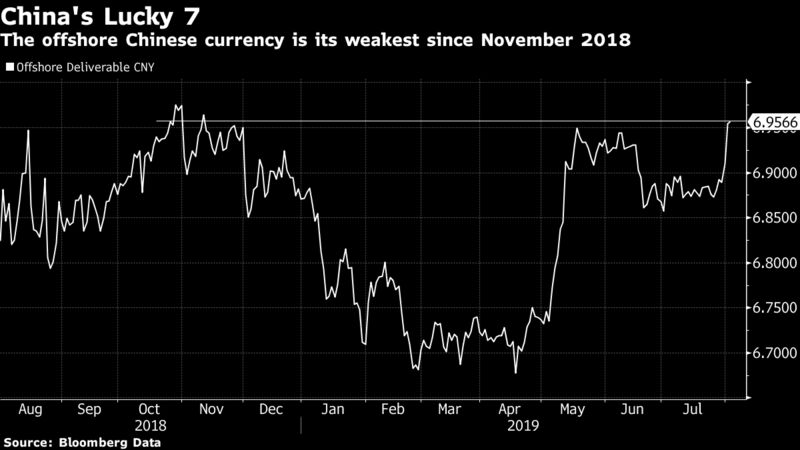

And then there is the issue of how China responds. The Chinese economy remains by far the greatest risk to the world economy, and this news can only increase the reasons for concern. And when it comes to retaliation, there is always the currency market. After years of intervening to keep its currency from strengthening too fast, China has more recently been intervening to keep it from weakening too fast. Many care about the level of 7 yuan to the dollar. Breach this, and it would appear that China is prepared to let its currency depreciate drastically in response to Trump’s trade moves. And judging by moves in the offshore market after the tariff announcement, that critical level is once again in play:

So if this is a cunning gambit by the president, rather than a considered response to the latest Chinese gambit in trade negotiations, it is a reckless and dangerous one indeed. But what is most important, and which seems to suggest that this is largely prompted by the Fed, is that it comes just as markets had seemed to lose their fears about trade.

Earlier this week, Gavekal Research’s Arthur Kroeber said that the macro risk from the trade talks was much diminished, and that they had become a “sideshow” to the far more important issue of the fundamental re-set in U.S.-China relations. I am quoting the following passage not to laugh at the way it appears to have been proved wrong, but to show that it made great and eminent sense:

It may seem bold to claim that macro risk from the trade war has evaporated. Yet the key outcome from June’s G20 meeting was that President Donald Trump backed down from his threat to impose up to 25% tariffs on an additional US$250bn or so of US imports from China. He did so even though China made no substantive new concessions to avoid the tariffs and get talks restarted.

The main reason for Trump’s climbdown was that these new tariffs (and any resulting retaliation from China) would have damaged market confidence and the US economy. Since it will be equally true in future that another major round of tariffs would hurt US market sentiment and the economy, and since Trump above all needs a strong economy during his 2020 re-election campaign, the likelihood of big new tariffs over the next 18 months is low. And any tariff threats from Trump during that period will quickly be judged by China, and the markets, as empty.

Hence, there is not much risk that global trade will be disrupted by massive tariffs, or that markets will be roiled by fears of tariffs. Similarly, a big threat from new tariffs—that China would respond by letting the renminbi depreciate significantly, as it did in April-August 2018—has been defused. During an uncertain spring, Beijing held the US dollar-renminbi rate at just below CNY7, with no direct intervention in forex markets. Other policy settings are designed in part with an eye to keeping the renminbi relatively strong: avoiding an over-stimulative monetary policy, and opening financial markets to encourage capital inflows.

All of this seems to make sense, and it evidently also made sense to markets that had settled back into a “risk-on” groove and appeared far less worried about trade talk. My best guess to explain the sudden escalation from Trump is that he was presented with a new and very appealing reason to raise tariffs – that this was the way he could force the Fed to cut rates. Now we will find out the consequences. |