Azure Cracks, AWS Strong: COVID-19 Stress Tests the Cloud

Kevin Xu

Author and founder of Interconnected.

2 Apr 2020

One of the most frequently discussed topics related to COVID-19’s multi-dimensional impact is the dramatic increase in “work from home” (WFH). A popular extension of that discussion is the various tools, applications, and technologies that are being used to make work from home...work! As it turns out, almost all of the commonly-used technologies for this purpose are either directly provided by large cloud platforms or run on one of them.

I’ve written quite a bit of analysis before on “stress testing” the various cloud platforms to assess their relative strengths and weaknesses, from looking at their other core businesses as a proxy, to the breadth and quality of their global data center coverage. Widespread WFH and demand for online entertainment and education, as more adults and children stay home, is giving every cloud an unprecedented stress test as we speak.

How are they faring so far?

Azure Showing Cracks

Microsoft’s Azure is showing signs of weakness as demand surges for its various collaboration and workplace products, from Office 865 to Windows Virtual Desktop to Teams (the workplace messaging service that competes with Slack). One misleading headline that’s been pushed out by Microsoft and unfortunately picked up by various tech media outlets, is the “ 775% increase” in Azure cloud service usage in geographical areas that are most committed to some form of social distancing or shelter-in-place policy.

I don’t blame the Microsoft PR team for pushing a positive narrative to make their products look good; that’s their job. But putting my analyst hat on, this narrative when not fully contextualized and understood, papers over cracks in the Azure infrastructure that are already showing.

First, this 8-plus-fold usage increase is limited to places where shelter-in-place is in full force as of the end of March, which at least in the United States, is only a small part of the country with densely populated urban areas: New York, California, New Jersey, Michigan, etc. Touting the percentage increase number is a classic trick of spinning massive growth out of a small or unknown base.

Second, just in March alone, multiple issues have occurred on various Microsoft cloud services: twice in just the last few weeks for European users of Teams, customers not getting the capacity they need in the US East Region, and XBox Live going down during a time when online gaming is surely surging. To put the timing in perspective, America and Europe only started taking COVID-19 seriously on a societal level in March. Parts of Azure began to fail almost as soon as people’s behaviors began to change.

Third, the way Azure has been dealing with and communicating about resource prioritization and changing service-level guarantees with free and paid-tier customers tells me that it has less extra capacity than what you might assume with a hypercloud provider. Yes, it’s definitely the right thing to do to prioritize capacity for any service or application that is supporting healthcare or other important efforts related to combating COVID-19, as is the case with PowerBI, Microsoft’s big data analytics tool. That being said, the other workarounds of “limits on free offers”, recommending “customers use alternative regions...that may have less demand surge”, and just encouraging “any customers experiencing allocation failures to retry…” indicate that there is little untapped resources to bring online to meet this demand surge. The only way forward is shifting existing resources around, keeping your paying customers happy, and forgoing the usual generosity for free users that can only happen in good times.

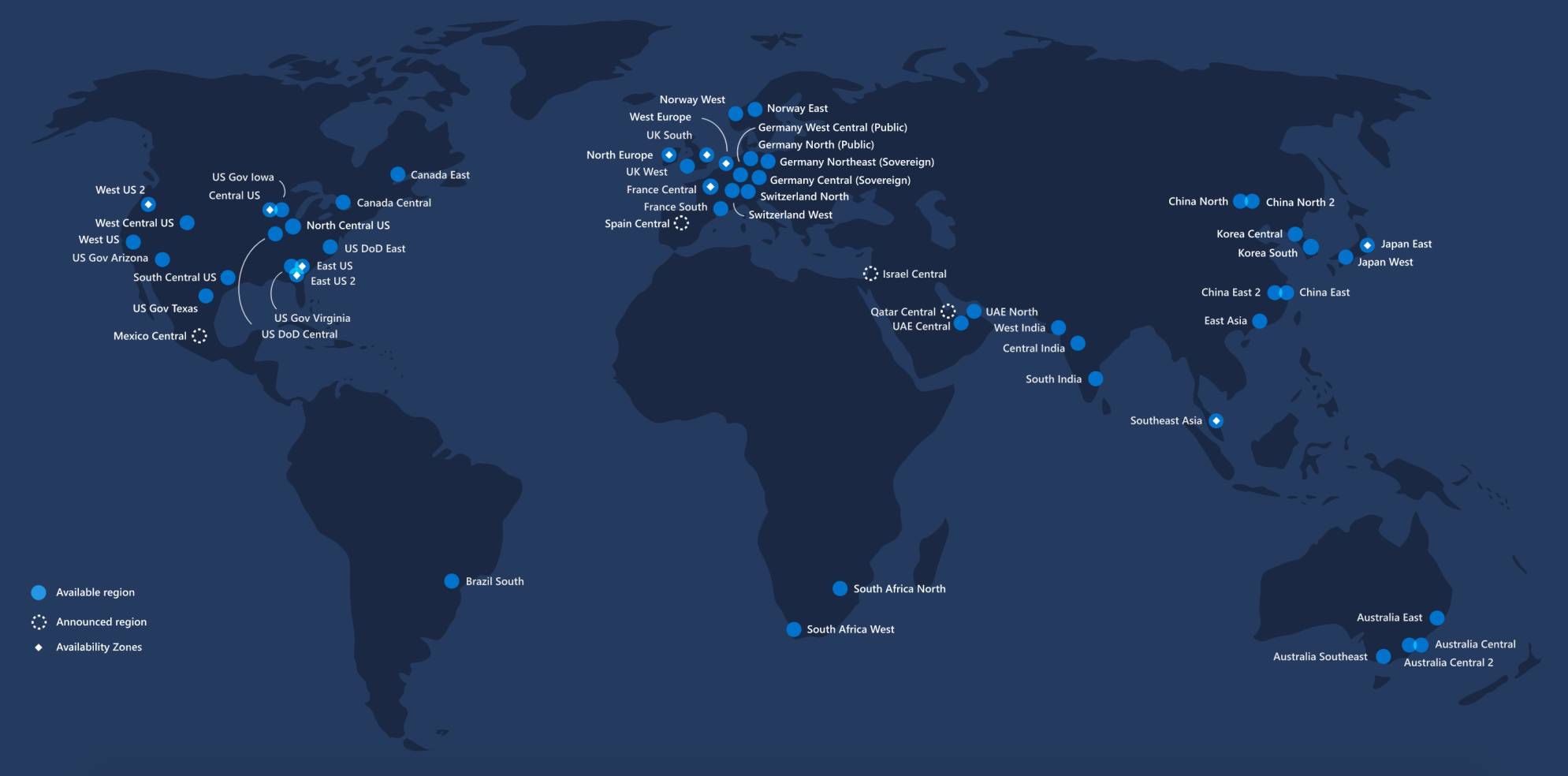

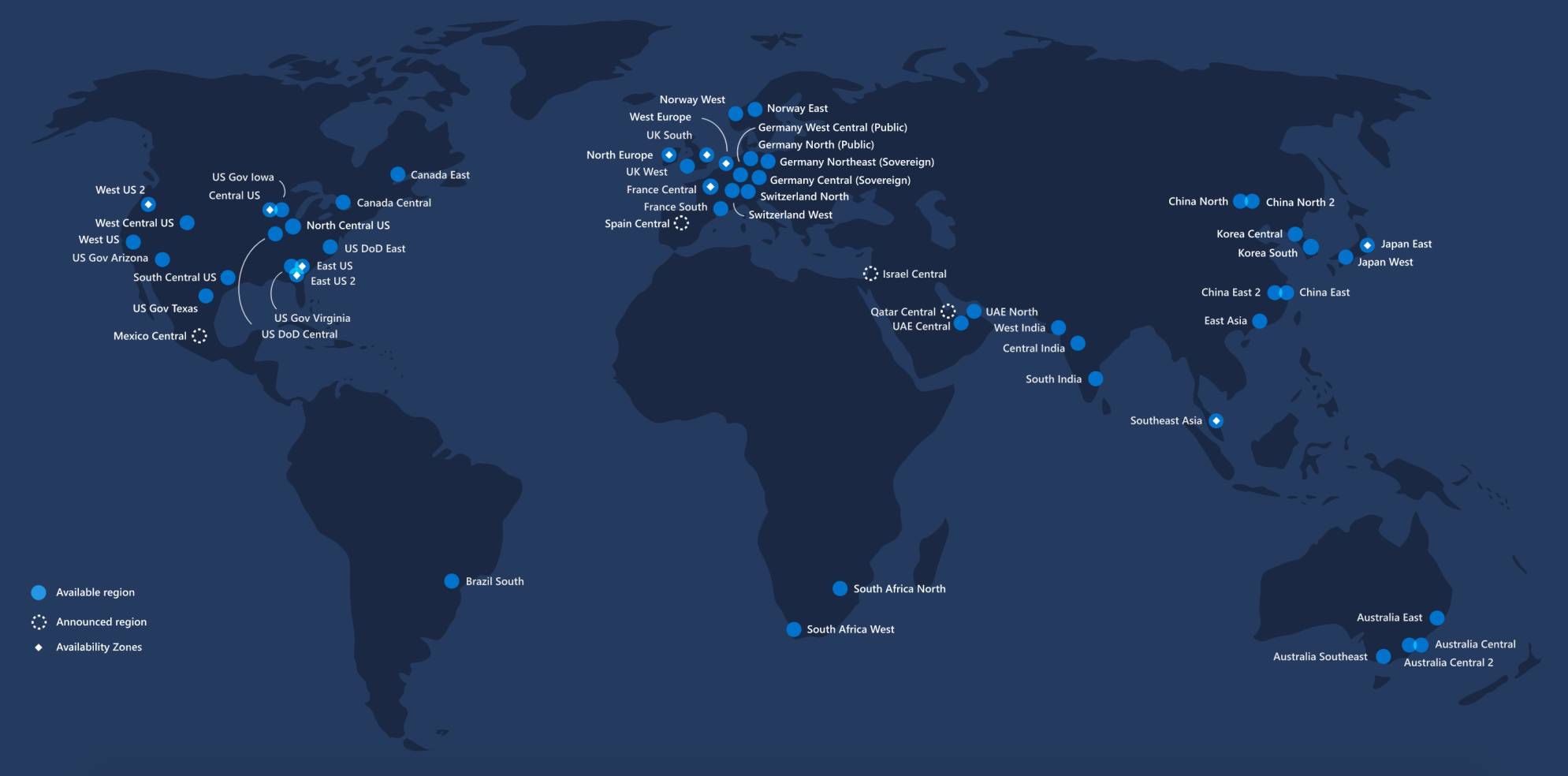

Azure cloud data center coverage and region types

__________________________________

All these cracks, and we may see more in the future, are not surprising. As I’ve noted in previous data center coverage and “stress test” analysis, Azure’s 54 live regions which are mostly of single availability zone (AZ) in their design is an architectural flaw. It provides less redundancy and reliability than a multi-AZ set up (usually three AZs), which is the default in AWS, GCP, and parts of Alibaba Cloud. Since Microsoft’s other businesses are either hardware or office software, with the exception of maybe XBox’s gaming, it generally lacks operational experience in running “always on” services and preparing for unanticipated traffic surges.

And all this is happening on Microsoft’s own home-grown services running on its own cloud, not even third party services built on top of Azure.

(Note: in order to avoid possible legal liability caused by the "775% increase" headline, Microsoft filed this 8K report to the SEC to clear up its motivation.)

AWS Standing Strong

Meanwhile, there has been little news coming out of AWS. In this case, no news is good news. AWS also sells its own workplace enterprise software, like Chime (videoconferencing, messaging) and WorkSpaces (remote desktop), while running plenty of 3rd party ones that have become household names during the COVID-19 induced surge in WFH: Zoom, Slack, the Atlassian suite, to name a few. (Worth noting: Zoom also uses Azure and its own data centers; proportion of workloads is not clear.) AWS also backs many entertainment services that people can’t live without while stuck at home: Netflix, Hulu, Twitch (owned by Amazon), Fortnite (owned by Epic Games, a big AWS customer).

Perhaps most important of all, AWS is the infrastructure for Amazon.com, Instacart, DoorDash and many others, whose delivery of grocery, meals, and other goods have made them essential services in keeping the self-quarantined population alive.

It’s safe to say that AWS runs a much bigger, if not more critical, chunk of the digital world than Azure. AWS has previously developed comprehensive processes for preventing outages during natural disasters and unexpected events, perhaps due to its own epic outages from before. And looks like it’s holding up well so far under the current crisis.

Myth of Adding Capacity During COVID-19

As for the other clouds: GCP, Alibaba Cloud, IBM, Oracle, Tencent Cloud, etc., not much COVID-19 related outages have been reported thus far. That’s partly due to the reality that these cloud vendors combined still run a smaller portion of the Internet than AWS and Azure; they are not big enough to be stress tested on the same level.

The standard external response from any cloud vendor that’s under resource constraint, like Azure, is that it will add more capacity as quickly as possible. There is no way to know for sure how much extra capacity each cloud has or should have. But we do know what they normally do to increase capacity.

From a technical angle, there are only three options. You either (1) build additional data centers and networking, which takes years, or (2) rack up more servers into your existing data centers, or (3) use software to boost throughput, performance, or multi-tenancy capacity in order to squeeze more out of the existing hardware. Under COVID-19, where human movement is limited, manufacturing capacity is constrained, especially in Asia where much of the servers are made, and supply chain and shipping capacity are reduced, the only near-term option is software.

And when the technical options are all exhausted, the only thing you can really do is use financial incentives and disincentives to control, limit, or shift usage, which appears to be what Azure is doing.

The economics of a cloud business, much like insurance, count on uncorrelated risks. So when these cloud vendors' PR departments try to calm your concerns with their "we are adding capacity" talking point, know that what they realistically can do is pretty limited.

At the end of the day, the economics of a cloud business, much like insurance, count on uncorrelated risks. Ideally, a platform runs many businesses with some unused capacity on reserve but not too much to be wasted, so when some businesses’ usages spike, they can use the extra capacity, and those spikes don’t lead to other businesses spiking too. If the spikes are related, it’s manageable as long as it’s anticipated, as is the case of e-commerce shopping holidays like Singles Day or Black Friday -- provision extra capacity ahead of time and simulate traffic surges to stress test.

Of course, we live far from an ideal world right now. When something like COVID-19 triggers many events all at the same time, many of which are impossible to anticipate, as a cloud platform, you either have the capacity or you don’t.

(This post was updated on April 2, 2020, after initial publication, with a link to Microsoft's 8K filing to the SEC regarding its "775% increase" blog post and a update/correction to AWS's own workplace software offering, which I failed to mention in the original version.)

interconnected.blog |