Re <<Reddit>>

I like Authers’ writing ...

bloomberg.com

GameStop Was as Fun as Pulling Teeth by the End

It was still a fantastic trade for those who got in early enough, or had the courage to short at the top.

John Authers

8 February 2021, 13:06 GMT+8

There was plenty of pain for some people in the GameStop trade.

Photographer: Vintage Images/Archive Photos/Getty Images

To get John Authers' newsletter delivered directly to your inbox, sign up here.

GameStop Game StoppedWelcome back to Points of Return. I devoted last week to maxillofacial surgery (in other words, I had two teeth extracted, and then the surgeon did a lot of tinkering with my jaw), which means I probably enjoyed myself almost as much as those who bought shares of GameStop Inc. the week before. For anyone unfamiliar with the story so far, this is what has happened to GameStop stock:

The incident is playing out with even more brutal speed than cynics like me had expected. The history of short squeezes (as recapped for Bloomberg Opinion by Niall Ferguson here) means that none of this should have been a great surprise. We already have some big losers, mainly short-selling hedge funds that were forced to cover, and retail investors who piled in at or near the top. The new model for retail trading, led by Robinhood Markets Inc., could yet prove another casualty. The winners, as of now, appear to be institutions that were long throughout, plus anyone who had the raw nerve to sell short near the top, along with the keen Reddit investors who had been in this trade for a while. For those who have held the shares more than a month, this has still been a fantastic trade.

Now, two questions loom large. First, how if at all will behavior change as a result of this? And second, what if anything should politicians and regulators do?

On the first, the most immediate impact is a possible withdrawal by specialist short-sellers. Big attacks on individual companies could be permanently weakened by the possibility of coordinated short squeezes by retail investors. Andrew Left of Citron Research has already announced that his company will stop publishing short-selling reports. This is bad for market hygiene, as it removes a key way for people to profit from the hard work of uncovering accounting fraud.

Beyond that, there is the issue of how long/short funds might behave. For many fund managers, short-selling is just a way to manage risk. They are primarily long, but balance risks with some short positions. If they are more reluctant to do this in future, they may also be more reluctant to take risks on the “long” side. This could lead, at the margin, to a more conservative market. This illustration from Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal Economics makes the point:

winning trades of recent years like being long Amazon and short any old retailer; or long Facebook and short an old media company, have stalled. Will those trades come back, or are we seeing a structural shift in the investment environment? If one wants to stay long Amazon on the basis that Jeff Bezos’s empire will crush all-comers, how is it possible to hedge if the option of shorting retailers that may be destroyed by Amazon is no longer practical? If condemned retailers can no longer be shorted, the question is perhaps: should Amazon longs be cut?

Now for the question of regulation. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has already consulted with other regulators, while congressional hearings are scheduled. Yellen is right to say: “We really need to make sure that our financial markets are functioning properly, efficiently and that investors are protected.” The question is whether intervening to thwart future GameStop incidents is the way to do this. Bloomberg Opinion’s Nir Kaissar argues that regulators should “ help unsophisticated investors get savvier rather than put gates around all retail investors.” This makes sense, but still leaves room for regulators to do more. In America, inevitably, courts will host much of the action.

Let me go through the debate in something like a Socratic dialogue. Regulators have to find the right balance in the classic tension between libertarianism and paternalism. I offered a series of bullet points on where I thought they should land in the last Points of Return. These are below in bold, with readers’ responses in italics. After that comes my latest reply. The issues are difficult; the case for a measure of paternalism is unpopular but stronger than it appears.

Regulators must respond with equity. Any suggestion that they are defending hedge funds against retail investors would be disastrous. Anything that clamps down on retail trading will have to be balanced by a serious attempt to stamp out “naked shorts” — the practice of selling a stock you don’t have, which led to the imbroglio at GameStop;Do you know for a fact that there was naked shorting? As some have pointed out, there is nothing to stop a share from being sold short more than once. If you short a stock, you sell it into the market. What is there to prevent the new owner of that share from lending it out to be shorted?

And why does retail trading need to be clamped down on after this? No one was forced to buy GME or AMC or any of the others. Please show me the actions that should be against the rules but currently aren’t.

OK, I don’t know for sure that there was naked shorting. But I don’t see that it’s in anyone’s interests to allow the total short position in a stock to become significantly bigger than the available float.

The issue of whether Robinhood and others really engaged in “gamification” — making trading more like a game, and helping to get people addicted to it — needs to be addressed. I think they have a case to answer.A maker of a product created it so that more people wanted to use it, call me shocked. Again, if Instagram or Facebook or Robinhood create a product that more people want to use why is it the government’s job to make sure they have fewer customers? Your complaint seems to be that people might do stupid things and Robinhood’s app’s design makes that easier. To go back to your driving analogy, does that mean cars should be limited by a governor so that they are unable to exceed the speed limit?

There are plenty of examples where companies can legally sell a product or service, but may not over-sell it. Opioids is one of the most pressing current examples. Some people (such as those who’ve just had maxillofacial surgery) might actually need industrial-strength opioids for a day or two. There are rightly many rules in place for stopping people over-using and over-prescribing them. Car speedometers have the speed limit marked clearly. If you exceed it, the car company has made sure that you’re aware you’re doing it. Something along those lines, at least, should be installed for Robinhood’s merry men.

The need to protect people from losing money they cannot afford to lose should remain paramount.Who gets to decide this? When Elon Musk was working on SpaceX he said there was a time when they were only days away from bankruptcy but were saved by a government contract. He had put all of his money into the company and would have been in trouble if it had gone under. Is that money he couldn’t afford to lose?

Ultimately, regulators answerable to elected politicians make such decisions. So some greater confidence in our democratic institutions would be nice. Avoiding that huge issue for now, some investments are riskier than others, and some require larger amounts of starting capital to have a reasonable chance of success. Those should be the elements that go into setting limits. Elon Musk had enough capital when he started out on SpaceX to have a chance of success. Had he lost and gone bankrupt, tough. Plainly, the risk of failure needs to be retained as a tool for avoiding moral hazard.

Redditors complain it would be unfair to stop them from taking risks that are allowed for hedge funds. There’s a good reason for this, though. Hedge funds are restricted to wealthy people who can afford losses, while others deserve more protection. I am sure that opinion will make me unpopular. A better question might be are the rules around “sophisticated investors” still appropriate in the modern era?This is a fair point. The rules around qualified investors who can put money into hedge funds have already been stretched. With so many more people asset-rich these days, it might be worth reassessing them. But this isn’t necessarily about the restriction of freedom, even if it is currently fashionable to couch it that way. I’ve never taken part in a short squeeze using borrowed money and single-stock call options, and this doesn’t bother me in the slightest. It’s not a freedom I need, or a freedom anyone other than a few professional investors could want.

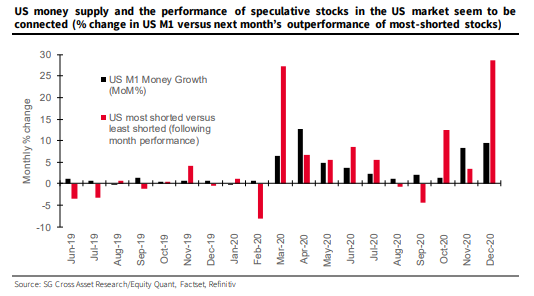

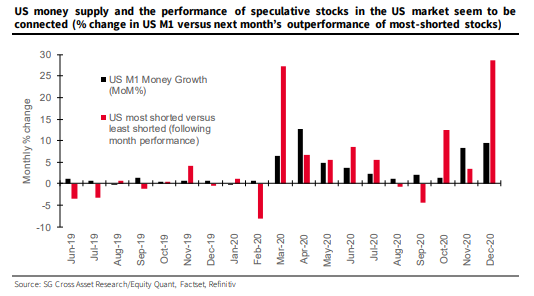

There is no libertarian objection to stopping behavior that endangers others. Libertarians can agree that nobody should be allowed to drive a car when drunk. Distorted markets, and particularly asset bubbles, lead to malinvestment and wasted capital, and ultimately to lost jobs. The Federal Reserve is adamant that it cannot and should not attempt to identify and deflate bubbles before they grow too big. Incidents like this suggest that they need to be more active. Do you really want the Federal Reserve to be focused on the prices of individual stocks? That seems like bringing a bunker buster to a knife fight. And again, who gets to decide if the price is wrong?It’s not a question of getting involved in individual stocks, but of macro-prudence. Knowing when a bull market has turned into a speculative bubble is difficult. But some kind of contra-cyclical system to tighten conditions when markets look excessive would be good. It’s the opposite of what we have at present. It is hard to imagine anything like GameStop if the Fed hadn’t cut rates to zero, promised to keep them there, and pumped more money into the system. Correlation doesn’t prove causation, but the following chart, from Andrew Lapthorne, chief quantitative strategist at Societe Generale SA, suggests that the performance of the most heavily shorted stocks took off after the Fed opened the monetary spigot last year:

This debate has further to run. But the case for doing something to limit the risk of further GameStops is real, and need not involve unacceptable incursions against individual liberty.

Survival TipsFollowing the Super Bowl, I have two. First, there’s no shame in standing on the shoulders of others. Watch this moment from half-time show by The Weeknd, one of the current wave of great Canadian musicians. This song, choreographed with dancers in head bandages, was written more than 40 years ago by Siouxsie and the Banshees: Happy House. There’s no plagiarism involved here. He’s taken a bitter and angry song by one of Britain’s greatest punk bands, who emerged from the unlovely London suburb of Bromley, and taken it via Toronto into something that can fill a football stadium in Florida. It’s cool — and my kids were impressed that I recognized the song.

The second tip concerns the great survivor himself, Tom Brady. The quarterback of the victorious Tampa Bay Buccaneers has now won seven Super Bowls — one more than any single team. At 43, he is the oldest player to take part. Yet this was his most emphatic victory yet, and he was named the most valuable player.

A lot of people dislike him, for some obvious reasons; he wins all the time, he had a very public friendship with Donald Trump, he’s very handsome, and he’s married to a supermodel. At the New England Patriots in Boston, where Brady won his first six Super Bowls, he was surrounded by a rather inchoate narrative that the entire organization was based on cheating, although the evidence for this was always threadbare. (Full disclosure: I’m a Boston sports fan.) So, few people were rooting for him. He should be an inspiration for us all. It’s taken immense self-control and discipline just to stay fit enough to do this. He also had the confidence after two decades at a great organization to try moving to another team. Good for him. As Tom Brady shows, joining a new team in late career, even if it involves leaving a great one, can give you a new lease of life.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

John Authers at jauthers@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

Read more opinion Follow @johnauthers on Twitter

Sent from my iPhone |