Re <<Slow down there>>

Speeding up, and timing interesting, from suspect MSM, but with a difference, actually backed by facts.

It appears that the coordinated actions, declaration of proto-war, by the like-minded is responsible and remains responsible for delayed understanding of one possible / probable way by which CoVid arose.

Australia in April 2020 called for a global inquiry into the origins of the pandemic, including China’s handling of the initial outbreak. Days later, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo used part of his Earth Day message to call on China to close its wet markets to “reduce risks to human health inside and outside of China.” In response, Geng Shuang, a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry, denied “wildlife wet markets” existed in the country. Government researchers now dismiss the market hypothesis completely.

Given war footing, what then happens is perfectly understandable, and then Afghanistan-ing happened by less coordinated actions of the same like-minded.

In any case, neither Fort Detrick nor Fauci is in the clear, as inadvertent discovery that both might have been involved in non-chance stuff per crimes-against-humanity Message 33430919 << 6. 7, 8 and 9. >> as opposed to illegal sale of critters.

The deer Message 33441487 investigation seems worthwhile for both historical / forensic as well as for future prevention reasons, but given that it is useful, it might be dropped.

As to Team China did not give early warning, a non-case, for China gave the strongest warning w/i 18 days of December 31st 2019, by shutting down a huge city for the world to see. Admittedly a lot can happen in 18-days, like closing down a sham war, losing a puppet government, and shamble a bug-out.

In the case of Covid, early warning of 18-months did no good, and in case of a war, early warning of 20 years, or arguably, a several centuries, did no good.

I lost track, but either or both DNC / GOP poopoo-ed Covid, then went batty over Covid, then poopoo-ed Covid, then … etc etc, as they also went hot and cold on the Afghanistan war.

DNC & GOP are however united on the CCP China China China war. Perhaps that one shall work out better.

bloomberg.com

Delayed Wuhan Report Adds Crucial Detail to Covid Origin Puzzle

A study documenting the trade in live wild animals at Wuhan wet markets stayed unpublished for more than a year.

August 17, 2021, 12:01 PM GMT+8

The origin story of Covid-19 remains a mystery mired in contentious geopolitical debate. But a research paper that languished in publishing limbo for a year and a half contains meticulously collected data and photographic evidence supporting scientists’ initial hypothesis—that the outbreak stemmed from infected wild animals—which prevailed until speculation that SARS-CoV-2 escaped from a nearby lab gained traction.

According to the report, which was published in June in the online journal Scientific Reports, minks, civets, raccoon dogs, and other mammals known to harbor coronaviruses were sold in plain sight for years in shops across the city, including the now infamous Huanan wet market, to which many of the earliest Covid cases were traced. The data in the report was collected over 30 months by Xiao Xiao, a virologist whose roles straddled epidemiology and animal research at the government-funded Key Laboratory of Southwest China Wildlife Resources Conservation and at Hubei University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

In May 2017, Xiao began surveying 17 shops at four Wuhan markets selling live wild animals. He was trying to find the source of a tick-borne, Lyme-like disease that had spread in Hubei province years earlier. He kept up monthly visits until November 2019, when the discovery of mysterious pneumonia cases that heralded the start of the Covid pandemic brought his visits to an abrupt end.

As the virus started to explode, Xiao recognized the potential significance of his data. In January of 2020, he collaborated with Zhou Zhaomin, a researcher at a wildlife resources laboratory affiliated with China’s Ministry of Education, and three seasoned scientists from the University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, on a manuscript that was submitted to a journal the following month. (They declined to name the publication). “We’d imagined that the journal we sent it to would say, ‘Fantastic! Of course we want these data out as quickly as we can. The World Health Organization would be absolutely thrilled to receive this information,’” says Chris Newman, a British ecologist who is one of the paper’s co-authors. But it was rejected. “They did not think it would have widespread appeal,” says Newman.

Had the study been made public right away, the search for the origins of the virus might have taken a very different course. Not only did the study contain conclusive evidence that live animals were being sold for human consumption at the epicenter of the outbreak, but Newman says he assumes Xiao collected blood-sucking ticks from the wild animals he studiously cataloged. The blood meals of frozen tick samples could be examined for traces of the coronavirus, which would be extremely helpful in identifying infected species prior to December 2019. Xiao didn’t respond to emails requesting comment.

In the first months of the epidemic, local researchers asserted that the new coronavirus resembled a spillover from animals, reminiscent of the emergence of the virus that caused severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in wet markets in Guangdong almost 20 years ago. They also readily acknowledged the presence of “a variety of live wild animals” at Wuhan markets.

Raccoon dog, Wuhan wet market, 2013.

Photo illustration by 731; Photo: Animal Equality

The Huanan market was shuttered in the early hours of Jan. 1, 2020, and its 678 stalls emptied and sanitized. In the middle of the month CNN broadcast unverified footage reportedly recorded in early December showing caged deer, marmots, and raccoon dogs there. Photographs of a menu board advertising the price and availability of exotic animals circulated online.

Disease detectives arriving from Beijing on the first day of 2020 ordered environmental samples to be collected from drains and other surfaces at the market. Some 585 specimens were tested, of which 33 turned out to be positive for SARS-CoV-2. “All current evidence points to wild animals sold illegally,” China Center for Disease Control Director George Gao and colleagues wrote in the agency’s weekly bulletin in late January. All but two of the positive specimens came from a cavernous and poorly-ventilated section of the market’s western wing, where many shops sold animals.

“We have found out which stalls on the seafood market in Wuhan had the virus,” Tan Wenjie, a researcher at China CDC’s viral disease control and prevention institute, was quoted telling the state-owned China Dailynewspaper days later. “It is an important discovery, and we will investigate which animal was the source.”

How Researchers Missed Clues in Wuhan

How Researchers Missed Clues in Wuhan

China temporarily banned the wildlife trade. The decision became permanent a month later and widened to prohibit human consumption of terrestrial wild animals.

A WHO-China joint mission to Wuhan to examine China’s response to the outbreak in February 2020 reported that an effort was under way to collect detailed records on the source and type of wildlife species sold at the Huanan market and the destination of those animals after the market was closed. But there’s no public record of that ever happening.

“Unfortunately, the apparent lack of direct animal sampling in the market may mean that it will be difficult, perhaps even impossible, to accurately identify any animal reservoir at this location,” Zhang Yongzhen and Edward Holmes, the scientists who published the first genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2, wrote in a commentary published in the journal Cell in March 2020.

As other nations began blaming the Chinese Communist Party for the pandemic, the government grew defensive. It may have been embarrassed that its citizens were still eating wild animals bought in wet markets—a well-known path for zoonotic disease transmission that China tried unsuccessfully to outlaw almost 20 years ago.

Australia in April 2020 called for a global inquiry into the origins of the pandemic, including China’s handling of the initial outbreak. Days later, then-U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo used part of his Earth Day message to call on China to close its wet markets to “reduce risks to human health inside and outside of China.”

In response, Geng Shuang, a spokesman for China’s Foreign Ministry, denied “wildlife wet markets” existed in the country. Government researchers now dismiss the market hypothesis completely. “SARS-CoV-2 could not have possibly evolved in an animal market in a big city and even less likely in a laboratory,” said a paper released in July, written by 22 researchers from mostly government-funded laboratories attached to the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

A more recent paper by government-affiliated scientists contends that the virus may have been imported from multiple locations worldwide, including parts of Europe where mink are raised in areas inhabited also by horseshoe bats known to harbor coronaviruses. “The official narrative changed not because the evidence changed,” says Robert Garry, a professor of microbiology and immunology at Tulane University’s School of Medicine in New Orleans. “A spillover from a wet market was what caused SARS, and, embarrassingly for China, those wet markets were never shut down.” Garry is the co-author of one of the earliest papers on the origins of Covid but wasn’t involved in the research on Wuhan’s markets.

Since he was not connected to a law enforcement agency, Xiao was granted “unique and complete access to trading practices,” he and his colleagues wrote. Seven of the shops he surveyed were in the Huanan market, which has been linked to two of the earliest documented cases of Covid-19. On each visit, Xiao asked vendors what species they had sold over the preceding month, documenting both their numbers and prices.

Xiao checked the animals for injuries and disease, noting that almost a third bore trapping and shooting wounds consistent with being caught in the wild, and that none of the shops displayed an origin or quarantine certificate, making the commerce “fundamentally illegal,” according to the study.

His animal logs included masked palm civets and raccoon dogs— both involved in the 2003 SARS outbreak—and other species susceptible to coronavirus infections, such as bamboo rats, minks, and hog badgers. Of the 38 species Xiao documented, 31 were protected.

A closed seafood wholesale market in Wuhan on Jan. 23, 2021.

Photo illustration by 731; Photo: AP Photo

Anyone caught violating China’s wild animal conservation law faces fines and up to 15 years of imprisonment. But enforcement was lax, as evidenced by the fact that many of the Wuhan shops displayed their wares openly, “caged, stacked and in poor condition,” Xiao observed in the report. Xiao estimated that 47,381 wild animals were sold in Wuhan over the survey period. These were luxury food items priced at up to $25 a kilogram ($11 per pound)—or more than four times costlier than pork, China’s main meat staple.

The initial manuscript was revised twice following feedback by a reviewer, and after more than six months of exchanges, was rejected.

The researchers revised the manuscript a third time and included data on China’s pangolin trade networks (an earlier study, later contested, had implicated pangolins in the virus’s spread to humans). In October 2020 they sent it to Scientific Reports.

Springer Nature, the publisher of Scientific Reports, forwarded a copy swiftly to the WHO as part of an agreement with the agency, says Ed Gerstner, Springer Nature’s director of journals, policy, and strategy. But the publisher emailed the paper, titled “Pangolin Trading in China: Wuhan’s Alibi in the Origin of Covid-19,” to a generic address at the WHO that functions as an inbox for unpublished research where it languished amid tens of thousands of submissions flooding the agency.

Springer Nature also sent a copy to Maria Van Kerkhove, the organization’s technical lead for Covid-19. Van Kerkhove says there were so many submissions related to the pandemic that she didn’t look at it right away, and she regrets there was no direct follow-up from the journal or by the authors. “It’s a shame this important information was not shared directly with the mission team while the team was in Wuhan and visited the markets,” she said in an email. “This paper would certainly have added great value.”

Newman says his Chinese co-authors never told him why they didn’t take their data directly to the WHO, but it’s possible they were more comfortable writing a report on market surveys for publishing in a journal, he says.

The China-based researchers would have had reason to be cautious. In February 2020, the China CDC prohibited scientists working on Covid-related research from sharing their data and required them to receive permission before conducting any studies or publishing the results. Days later, a special panel convened by China’s top executive body to oversee coronavirus research took control of all publication work related to the pandemic for “coordinated deployment.”

An international group of experts convened by the WHO to research the origins of Covid traveled to Wuhan earlier this year—a trip that might have yielded different results if the scientists had known about Xiao’s work.

By the time the team visited the Huanan market in the afternoon of Jan. 31—more than a year after its closure—little remained to assist the kind of epidemiological sleuthing that led SARS investigators to Himalayan palm civets, raccoon dogs, and Chinese ferret-badgers sold in live-animal markets in Guangdong almost two decades ago.

The researchers noted a mixed smell of animals and disinfectant in some areas of the market, but they were told by the market’s manager that they were probably smelling the lingering stench of rotten meat and sewage, according to the official joint WHO-China report released in March 2021.

Chinese officials briefing the visitors told them 10 Huanan shops had been found to be selling frozen “domesticated” wild animals, including bamboo rats—some sourced from Yunnan province, where scientists found a coronavirus that most closely matches SARS-CoV-2 in horseshoe bats. But no live animals had been seen before the market was closed, the official said.

The researchers saw nothing to dispute that. They were invited to quiz two Wuhan residents whom they were told had shopped there regularly for 20 and 30 years and who, according to the report, said they “had never witnessed any live animals being sold.”

Earlier the same day, the international research team visited Wuhan’s larger Baishazhou market, where Xiao had regularly surveyed two sellers of live wild animals. Yet when the researchers were there they were told that only frozen food, ingredients, and kitchenware were on offer. Liang Wannian, an epidemiologist who led the Chinese experts collaborating with the WHO-convened team, says his group had no knowledge of Xiao’s data either.

Among the earliest clusters of infections recorded in Wuhan, one involved three Covid cases among staff working at a stall in Huanan. One of the employees, a 32-year-old who fell ill on Dec. 19, traded goods back and forth between the Huanan and Baishazhou markets.

A confirmed case linking two markets that sold wild animals is “very intriguing,” says Stephen Goldstein, a research associate in evolutionary virology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. But tracing any contact the employee might have had with infected wildlife is impossible now that the animals are long gone. As for the existence of a flourishing live wild animal business, “It seems to me, at a minimum, that local or regional authorities kept that information quiet deliberately,” he says. “It’s incredible to me that people theorize about one type of cover-up, but an obvious cover-up is staring them right in the face.”

U.S. intelligence agencies will report their own findings on Covid’s origins later this month. But with only circumstantial evidence remaining, the world may now never know what caused the outbreak. “It is unclear why earlier initiatives within China to locate source animals for SARS-CoV-2 were curtailed, and now appear unfortunately to have stopped,” says Tulane’s Garry. “Instead, the focus is on highly implausible origin scenarios. If we continue to place politics over science, humanity will again be unprepared for the next emergence of a pandemic virus.”

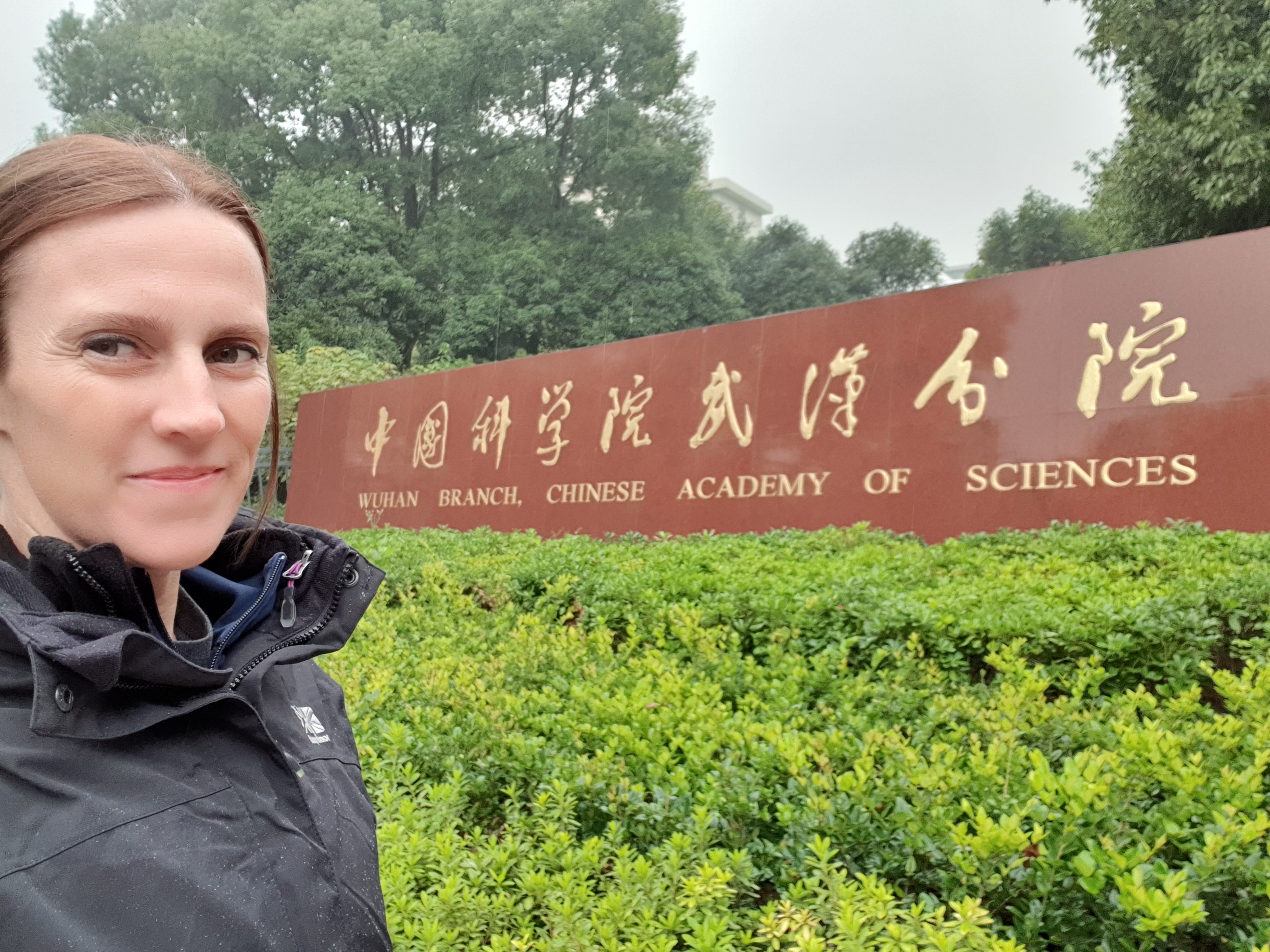

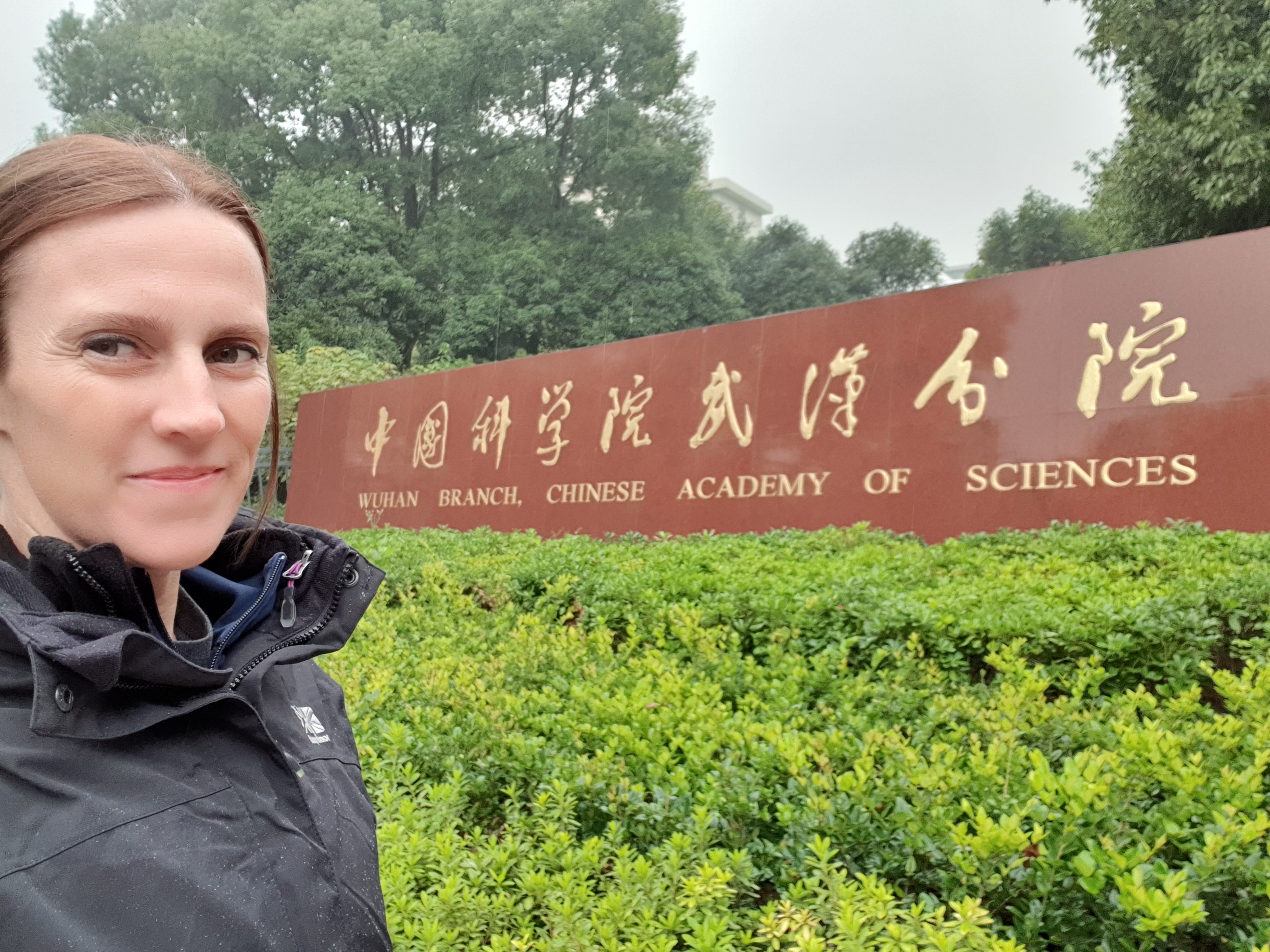

Read next: The Last—And Only—Foreign Scientist in the Wuhan Lab Speaks Out

bloomberg.com

The Last—And Only—Foreign Scientist in the Wuhan Lab Speaks OutVirologist Danielle Anderson paints a very different picture of the Wuhan Institute.

More stories by Michelle Fay CortezJune 28, 2021, 5:00 AM GMT+8

Danielle Anderson was working in what has become the world’s most notorious laboratory just weeks before the first known cases of Covid-19 emerged in central China. Yet, the Australian virologist still wonders what she missed.

An expert in bat-borne viruses, Anderson is the only foreign scientist to have undertaken research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s BSL-4 lab, the first in mainland China equipped to handle the planet’s deadliest pathogens. Her most recent stint ended in November 2019, giving Anderson an insider’s perspective on a place that’s become a flashpoint in the search for what caused the worst pandemic in a century.

The emergence of the coronavirus in the same city where institute scientists, clad head-to-toe in protective gear, study that exact family of viruses has stoked speculation that it might have leaked from the lab, possibly via an infected staffer or a contaminated object. China’s lack of transparency since the earliest days of the outbreak fueled those suspicions, which have been seized on by the U.S. That’s turned the quest to uncover the origins of the virus, critical for preventing future pandemics, into a geopolitical minefield.

The work of the lab and the director of its emerging infectious diseases section— Shi Zhengli, a long-time colleague of Anderson’s dubbed ‘Batwoman’ for her work hunting viruses in caves—is now shrouded in controversy. The U.S. has questioned the lab’s safety and alleged its scientists were engaged in contentious gain of function research that manipulated viruses in a manner that could have made them more dangerous.

It’s a stark contrast to the place Anderson described in an interview with Bloomberg News, the first in which she’s shared details about working at the lab.

The BSL-4 lab, center, at the Wuhan Institute of Virology in May 2020.

Photographer: Hector Retamal/AFP/Getty Images

Half-truths and distorted information have obscured an accurate accounting of the lab's functions and activities, which were more routine than how they’ve been portrayed in the media, she said.

“It’s not that it was boring, but it was a regular lab that worked in the same way as any other high-containment lab,” Anderson said. “What people are saying is just not how it is.”

Now at Melbourne’s Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, Anderson began collaborating with Wuhan researchers in 2016, when she was scientific director of the biosafety lab at Singapore’s Duke-NUS Medical School. Her research—which focuses on why lethal viruses like Ebola and Nipah cause no disease in the bats in which they perpetually circulate—complemented studies underway at the Chinese institute, which offered funding to encourage international collaboration.

A rising star in the virology community, Anderson, 42, says her work on Ebola in Wuhan was the realization of a life-long career goal. Her favorite movie is “Outbreak,” the 1995 film in which disease experts respond to a dangerous new virus—a job Anderson said she wanted to do. For her, that meant working on Ebola in a high-containment laboratory.

Anderson’s career has taken her all over the world. After obtaining an undergraduate degree from Deakin University in Geelong, Australia, she worked as a lab technician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, then returned to Australia to complete a PhD under the supervision of eminent virologists John Mackenzie and Linfa Wang. She did post-doctoral work in Montreal, before moving to Singapore and working again with Wang, who described Anderson as “very committed and dedicated,” and similar in personality to Shi.

“They’re both very blunt with such high moral standards,” Wang said by phone from Singapore, where he’s the director of the emerging infectious diseases program at the Duke-NUS Medical School. “I’m very proud of what Danielle’s been able to do.”

On the GroundAnderson was on the ground in Wuhan when experts believe the virus, now known as SARS-CoV-2, was beginning to spread. Daily visits for a period in late 2019 put her in close proximity to many others working at the 65-year-old research center. She was part of a group that gathered each morning at the Chinese Academy of Sciences to catch a bus that shuttled them to the institute about 20 miles away.

As the sole foreigner, Anderson stood out, and she said the other researchers there looked out for her.

“We went to dinners together, lunches, we saw each other outside of the lab,” she said.

Anderson in Wuhan in 2019.

Source: Danielle Anderson

From her first visit before it formally opened in 2018, Anderson was impressed with the institute’s maximum biocontainment lab. The concrete, bunker-style building has the highest biosafety designation, and requires air, water and waste to be filtered and sterilized before it leaves the facility. There were strict protocols and requirements aimed at containing the pathogens being studied, Anderson said, and researchers underwent 45 hours of training to be certified to work independently in the lab.

The induction process required scientists to demonstrate their knowledge of containment procedures and their competency in wearing air-pressured suits. “It’s very, very extensive,” Anderson said.

Entering and exiting the facility was a carefully choreographed endeavor, she said. Departures were made especially intricate by a requirement to take both a chemical shower and a personal shower—the timings of which were precisely planned.

Wuhan Scientist: I Don't Believe the Virus Was Manmade

WATCH: Last Foreign Wuhan Lab Scientist

Special DisinfectantsThese rules are mandatory across BSL-4 labs, though Anderson noted differences compared with similar facilities in Europe, Singapore and Australia in which she’s worked. The Wuhan lab uses a bespoke method to make and monitor its disinfectants daily, a system Anderson was inspired to introduce in her own lab. She was connected via a headset to colleagues in the lab’s command center to enable constant communication and safety vigilance—steps designed to ensure nothing went awry.

However, the Trump administration’s focus in 2020 on the idea the virus escaped from the Wuhan facility suggested that something went seriously wrong at the institute, the only one to specialize in virology, viral pathology and virus technology of the some 20 biological and biomedical research institutes of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Shi Zhengli in the BSL-4 lab at the Wuhan Institute in 2017.

Source: Feature China/Barcroft Media/Getty Images

Virologists and infectious disease experts initially dismissed the theory, noting that viruses jump from animals to humans with regularity. There was no clear evidence from within SARS-CoV-2’s genome that it had been artificially manipulated, or that the lab harbored progenitor strains of the pandemic virus. Political observers suggested the allegations had a strategic basis and were designed to put pressure on Beijing.

And yet, China’s actions raised questions. The government refused to allow international scientists into Wuhan in early 2020 when the outbreak was mushrooming, including experts from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, who were already in the region.

Beijing stonewalled on allowing World Health Organization experts into Wuhan for more than a year, and then provided only limited access. The WHO team’s final report, written with and vetted by Chinese researchers, played down the possibility of a lab leak. Instead, it said the virus probably spread via a bat through another animal, and gave some credence to a favored Chinese theory that it could have been transferred via frozen food.

Never SickChina’s obfuscation led outside researchers to reconsider their stance. Last month, 18 scientists writing in the journal Science called for an investigation into Covid-19’s origins that would give balanced consideration to the possibility of a lab accident. Even the director-general of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, said the lab theory hadn’t been studied extensively enough.

But it’s U.S. President Joe Biden’s consideration of the idea—previously dismissed by many as a Trumpist conspiracy theory—that has given it newfound legitimacy. Biden called on America’s intelligence agencies last month to redouble their efforts in rooting out the genesis of Covid-19 after an earlier report, disclosed by the Wall Street Journal, claimed three researchers from the lab were hospitalized with flu-like symptoms in November 2019.

What the World Wants China to Disclose in Wuhan Lab Leak Probe

Anderson said no one she knew at the Wuhan institute was ill toward the end of 2019. Moreover, there is a procedure for reporting symptoms that correspond with the pathogens handled in high-risk containment labs.

“If people were sick, I assume that I would have been sick—and I wasn’t,” she said. “I was tested for coronavirus in Singapore before I was vaccinated, and had never had it.”

World Health Organization experts were provided limited access at the Wuhan Institute of Virology when they visited in February this year.

Photographer: Hector Retamal/AFP/Getty Images

Not only that, many of Anderson’s collaborators in Wuhan came to Singapore at the end of December for a gathering on Nipah virus. There was no word of any illness sweeping the laboratory, she said.

“There was no chatter,” Anderson said. “Scientists are gossipy and excited. There was nothing strange from my point of view going on at that point that would make you think something is going on here.”

The names of the scientists reported to have been hospitalized haven’t been disclosed. The Chinese government and Shi Zhengli, the lab’s now-famous bat-virus researcher, have repeatedly denied that anyone from the facility contracted Covid-19. Anderson’s work at the facility, and her funding, ended after the pandemic emerged and she focused on the novel coronavirus.

‘I’m Not Naive’It’s not that it’s impossible the virus spilled from there. Anderson, better than most people, understands how a pathogen can escape from a laboratory. SARS, an earlier coronavirus that emerged in Asia in 2002 and killed more than 700 people, subsequently made its way out of secure facilities a handful of times, she said.

If presented with evidence that such an accident spawned Covid-19, Anderson “could foresee how things could maybe happen,” she said. “I’m not naive enough to say I absolutely write this off.”

And yet, she still believes it most likely came from a natural source. Since it took researchers almost a decade to pin down where in nature the SARS pathogen emerged, Anderson says she’s not surprised they haven’t found the “smoking gun” bat responsible for the latest outbreak yet.

The Wuhan Institute of Virology is large enough that Anderson said she didn’t know what everyone was working on at the end of 2019. She is aware of published research from the lab that involved testing viral components for their propensity to infect human cells. Anderson is convinced no virus was made intentionally to infect people and deliberately released—one of the more disturbing theories to have emerged about the pandemic’s origins.

Gain of FunctionAnderson did concede that it would be theoretically possible for a scientist in the lab to be working on a gain of function technique to unknowingly infect themselves and to then unintentionally infect others in the community. But there’s no evidence that occurred and Anderson rated its likelihood as exceedingly slim.

Getting authorization to create a virus in this way typically requires many layers of approval, and there are scientific best practices that put strict limits on this kind of work. For example, a moratorium was placed on research that could be done on the 1918 Spanish Flu virus after scientists isolated it decades later.

Even if such a gain of function effort got clearance, it’s hard to achieve, Anderson said. The technique is called reverse genetics.

“It’s exceedingly difficult to actually make it work when you want it to work,” she said.

Anderson’s lab in Singapore was one of the first to isolate SARS-CoV-2 from a Covid patient outside China and then to grow the virus. It was complicated and challenging, even for a team used to working with coronaviruses that knew its biological characteristics, including which protein receptor it targets. These key facets wouldn’t be known by anyone trying to craft a new virus, she said. Even then, the material that researchers study—the virus’s basic building blocks and genetic fingerprint—aren’t initially infectious, so they would need to culture significant amounts to infect people.

Anderson is convinced no virus was made intentionally to infect people and deliberately released—one of the more disturbing theories to have emerged.

Photographer: James Bugg/Bloomberg

Despite this, Anderson does think an investigation is needed to nail down the virus’s origin once and for all. She’s dumbfounded by the portrayal of the lab by some media outside China, and the toxic attacks on scientists that have ensued.

One of a dozen experts appointed to an international taskforce in November to study the origins of the virus, Anderson hasn’t sought public attention, especially since being targeted by U.S. extremists in early 2020 after she exposed false information about the pandemic posted online. The vitriol that ensued prompted her to file a police report. The threats of violence many coronavirus scientists have experienced over the past 18 months have made them hesitant to speak out because of the risk that their words will be misconstrued.

The elements known to trigger infectious outbreaks—the mixing of humans and animals, especially wildlife—were present in Wuhan, creating an environment conducive for the spillover of a new zoonotic disease. In that respect, the emergence of Covid-19 follows a familiar pattern. What’s shocking to Anderson is the way it unfurled into a global contagion.

“The pandemic is something no one could have imagined on this scale,” she said. Researchers must study Covid's calamitous path to determine what went wrong and how to stop the spread of future pathogens with pandemic potential.

“The virus was in the right place at the right time and everything lined up to cause this disaster.”

Sent from my iPad |