a good story

“I was born and raised here,” said Yu. “My dad would tell me of all of these beautiful places he saw when diving. When I visited those sites, it was just mud. The corals had disappeared. But they are coming back. If you build it, they will come.”

bloomberg.com

Vulnerable Coral Moved to a 3D-Printed Reef in Hong Kong Is Thriving

Fragments of coral inserted in clay tiles are surviving and growing, researchers say, a hopeful sign for saving the animals at risk from climate change.

2 November 2022 at 12:01 GMT+8

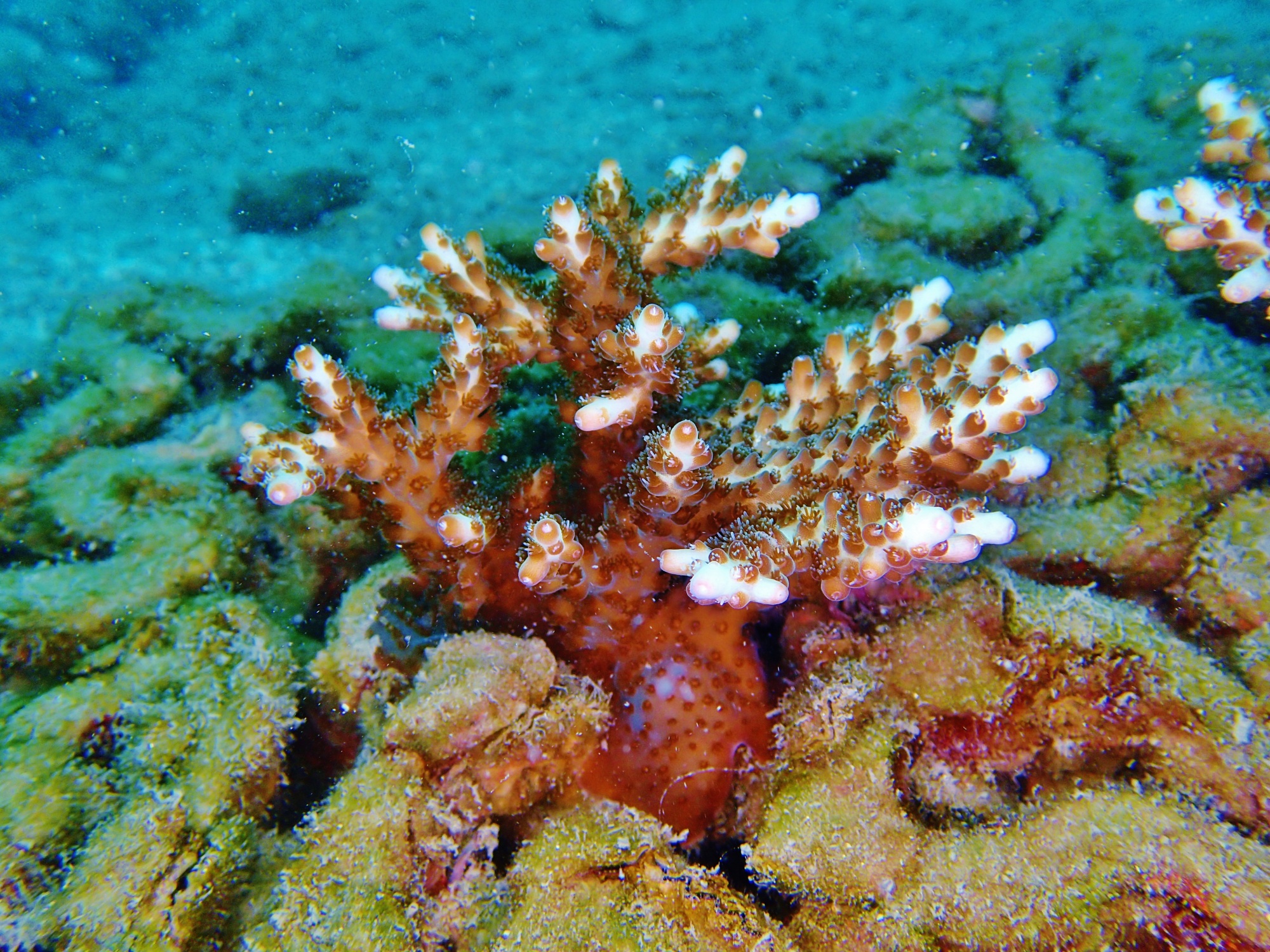

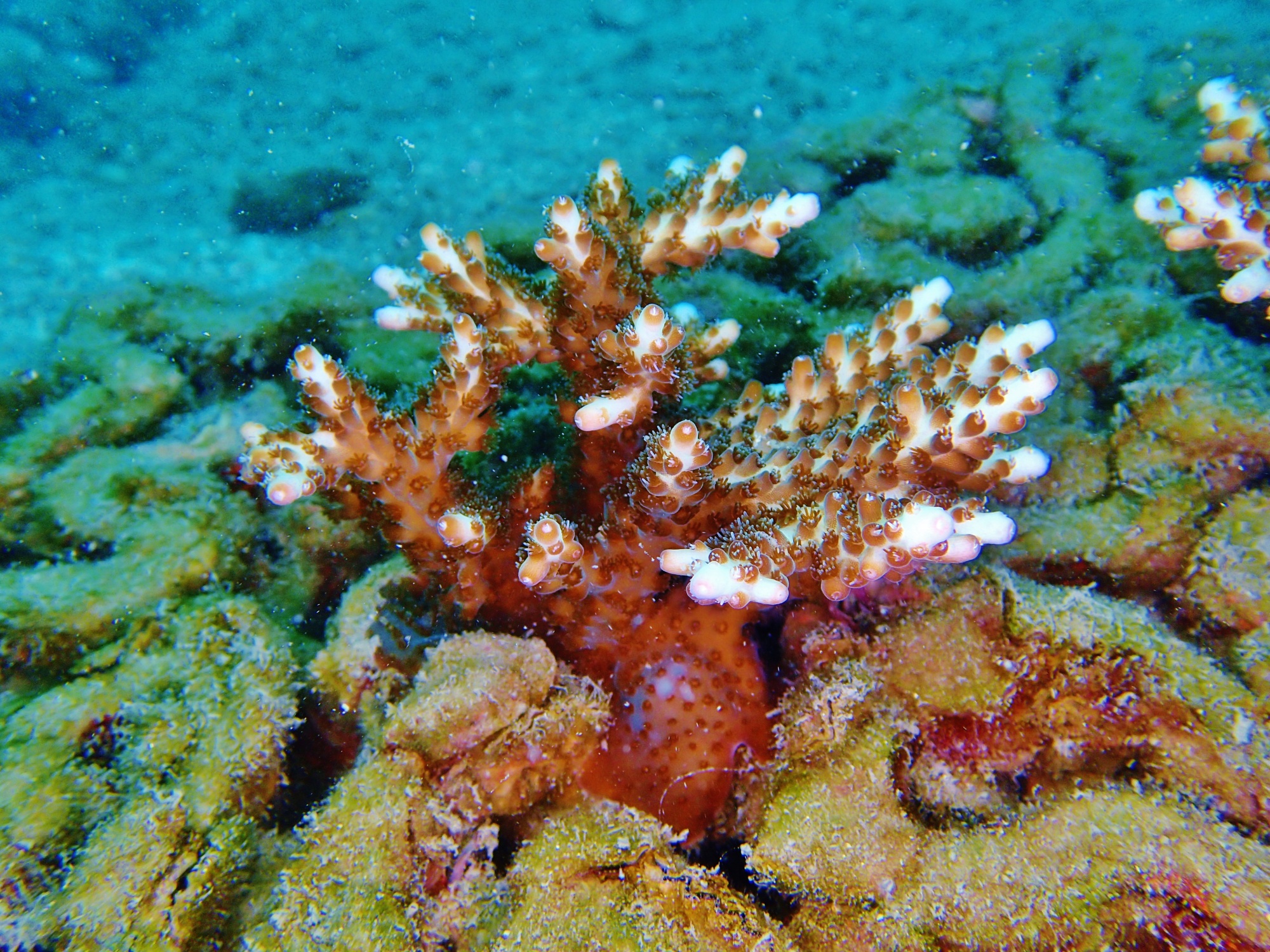

Coral transplanted on Archireef’s tiles.

Phil Thompson/Archireef

In the subtropical sea off northeast Hong Kong, orange and white-striped clownfish somersault like acrobats, black sea urchins furtively wiggle their antennas and crabs shuttle between crevices in a leggy panic.

Much of this activity in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park gravitates around corals that are thriving on an artificial reef made of 3D-printed terracotta tiles, installed two years ago by researchers at the University of Hong Kong (HKU).

“The corals have grown so much since I last dived here,” said Vriko Yu on a recent afternoon, moments after resurfacing in the protected, jade-colored waters. “What excites me is the way that you can see the species are quickly making a home here.”

Vriko Yu, Archireef’s co-founder and CEO

Photographer: Peter Yeung

The reef tiles are thought to be the first use of clay for 3D printing in the world. They were produced by Archireef, a company spun off from the university and co-founded by Yu, a former PhD student, and marine biology professor David Baker. The company will present its work at the upcoming COP27 climate summit.

Its terracotta hexagons could be a building block in efforts to protect and restore vulnerable coral reefs, which cover less than 1% of the ocean floor but host more than 25% of all marine life. They might also help to cultivate corals that are more resilient to waters warming rapidly because of climate change.

Hong Kong’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) launched efforts to restore the reefs at Hoi Ha Wan after toxic “ red tide” algae blooms in 2015 and 2016 killed off 90% of its Platygyra, one of the major local coral species.

Initially, in late 2016, scientists attempted to revive the reefs by gluing living coral fragments directly onto rocks. But the corals grew very slowly, often detaching and dying. In response, researchers developed the 3D-printed tiles. In 2020, divers placed 400 coral fragments, which had been naturally dislodged in the ocean, into the ridges of the tiles, which measure 50 centimeters square (about 20 inches by 20 inches) and weigh around 15 kilograms (33 pounds) each.

Designed to mimic the complex shape of Platygyra, or “ brain coral,” the tiles contain crevices and niches for coral seedlings and marine life to settle in while also minimizing buildup of the sediment prevalent in Hong Kong’s waters. The bottom half of the tile is designed like a snowshoe, providing stability on sandy seabeds, which have become common due to Hong Kong’s high rates of bioerosion.

Divers planting coral fragments on a tile whose grooves mimic those of Platygyra coral.

Photo: AFCD/Archireef

“Corals aren’t like trees, they don’t have roots,” says Yu. “They can’t attach to sand. They must be connected to substrate. So, we had to kind of renovate the sea floor.”

Concrete, which is often used in coral restoration projects, can affect the chemical balance of coral ecosystems. But clay is slightly acidic like the calcium carbonate found in real coral reefs and will, in theory, erode over decades, leaving behind healthy coral. The 3D printing process is cheaper than pouring concrete and allows for customization, with bespoke designs combatting specific environmental problems posed by a location.

“Hong Kong corals are incredibly resilient to change … Some consider them ‘super corals’ for that reason”

The scientists seeded three dominant local genuses of coral, Acropora and Pavona as well as Platygyra, and are monitoring a number of key factors: which coral combinations produce faster regrowth and coverage; which generate the greatest increase in biodiversity; and the rate of survival.

As of late August, after just over two years of deployment, the survival rate for the corals on the 3D-printed reef tiles is 98% — five times the previous level and more than that recorded in almost all other coral restoration projects. Despite the typically slow growth rates in subtropical waters, the Acropora have grown by 70%, the Pavona by 37% and the Platygyra by 25%. Many tiles are now barely visible, such is the mass of coral, and while biodiversity studies aren’t due until the end of the year, there have been sightings of nesting cuttlefish, drawn to structures to keep their eggs safe.

Coral and fish at the site in Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park.

Photographer: Peter Yeung

Hong Kong’s corals are of special interest to marine scientists because of the region’s huge changes in seasonal water temperatures, which rise or fall by as much as 15C, according to Jonathan Cybulski, a Smithsonian fellow and former historical ecologist at HKU. Studying these corals could help researchers understand why they are so hardy and provide survival lessons for corals elsewhere. “Hong Kong corals are incredibly resilient to change,” Cybulski says. “There’s incredible fluctuation. Some consider them ‘super corals’ for that reason. In the Great Barrier Reef, there’s only a couple of degrees change.”

Hong Kong is home to over 100 coral species, more than the Caribbean. Yet according to Cybulski, who analyzed fossils collected from more than 10 sites, the number of corals in Hong Kong has declined by 40% due to overfishing, land development and pollution. Research he and collaborators published in 2020 did not find evidence of climate change playing a significant role in that decline yet.

Globally, though, global warming is a dire risk to coral reefs, an estimated 70% to 90% of which may be lost. Huge losses have been incurred already. In 2016 and 2017 alone, 89% of new corals on the Great Barrier Reef, the world’s largest coral reef system, died as a result of climate change-induced mass bleaching.

Emma Camp, a coral expert at the University of Technology Sydney in Australia, says site-specific and evidence-based approaches like Archireef’s will be crucial to success in coral restoration. “It’s brilliant,” she says. “There is not one-size-fits-all when it comes to finding a solution. Local knowledge and context must be applied.”

A turtle swimming over an Indian Ocean reef damaged by bleaching in 2016.

Photo: ARC CoE for Coral Reef Studies

Camp points to a variety of approaches used across the globe, from the Great Barrier Reef’s Coral Nurture Program, which has outplanted 72,000 corals using a device known as a Coralclip, to the 18,000 “ coral spiders” deployed in Indonesia to restore coral in the gaps between live reefs.

“One of the big challenges is defining what success is,” she adds. “We’ve outplanted X number of corals. But what is the biodiversity created? How fast did they grow? Did they become reproductive? Will they survive in the future? How cost effective is it?”

After striking a deal with a corporate client or governments to sponsor a restoration project, Archireef identifies a site for restoration, installs the tiles, and, crucially, manages the site for up to five years on a “subscription” basis. By the end of 2022, Archireef hopes to deploy tiles in Hong Kong’s Deep Water Bay and in Abu Dhabi, adding to the three Hong Kong sites it already operates. Each project costs between $100,000 and $400,000. The startup also plans to refine the 3D-printing process and is exploring alternative tile materials, including materials derived from the ocean, since firing clay is still energy intensive.

Back at Hong Kong’s Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park, there is at least hope on the horizon as the sun begins to set over the South China Sea and its steadily growing population of reinvigorated coral.

“I was born and raised here,” said Yu. “My dad would tell me of all of these beautiful places he saw when diving. When I visited those sites, it was just mud. The corals had disappeared. But they are coming back. If you build it, they will come.” |