Re <<wonder how Cohen (a very common name*) got along with Borodin - same ethnicity opposite ideology>>

... very complicated. Had Eugene not hired Cohen, Cohen would not have suffered wound whilst saving life of Sun, and Borodin would have had no one to advise, and and and ... and a lot more Jewish folks would have died, in Europe and is then Palestine

hpcbristol.net

asianjewishlife.org

<<When Stalin sent an agent, Michael Borodin, to promote communism in China, Cohen communicated with him in Yiddish while conspiring against him behind his back. Morris was friendly with Zhou Enlai, founder of the Chinese Communist party, but also had close ties ardent capitalists such as the powerful Soong family, notably T. V. Soong, brother of Madame Sun and Madame Chiang Kai-shek.>>

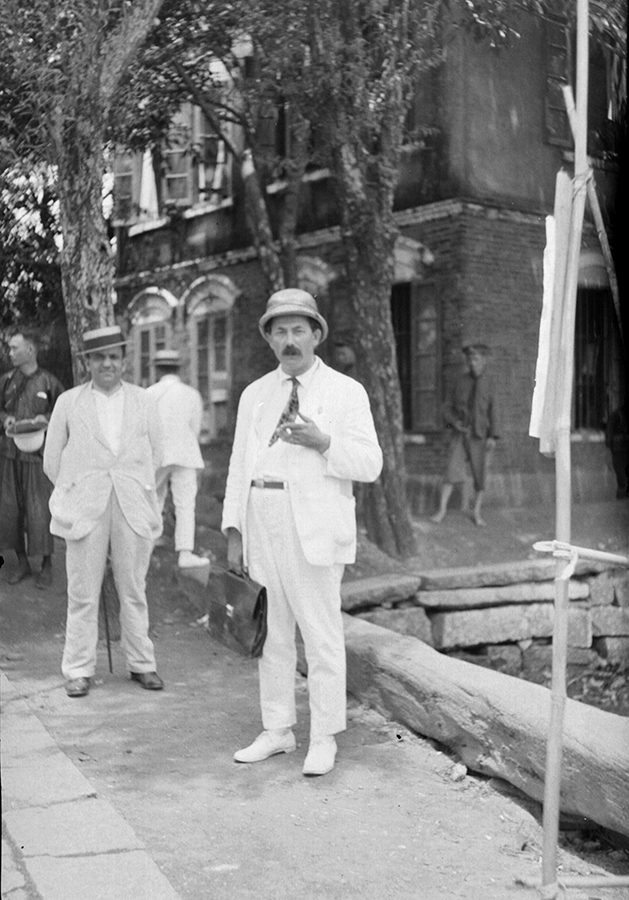

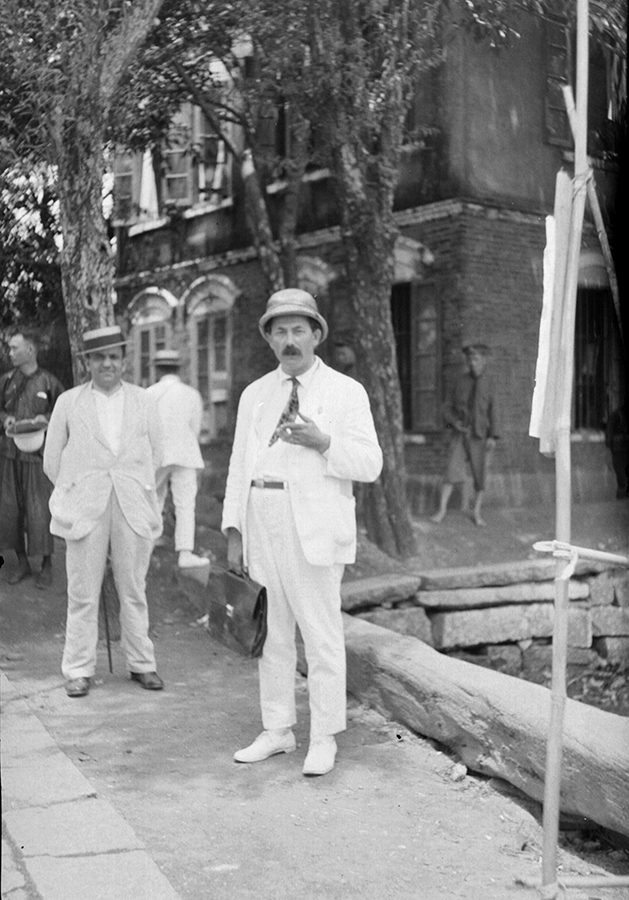

Cohen with Communist party leaders in Mainland China. Collection of Victor D. Cooper, courtesy of Daniel S. Levy

In 1966, Cohen was invited to make an official visit to China in 1966, for the hundredth anniversary of Sun Yat-sen’s birth, where he was the only Westerner on the podium. He stopped en route in Israel, returning in 1969 when, according to Cyril Sherer, he was again asked to intervene with the Chinese. The detonators for button mines, small plastic explosives used by Arab terrorists against Israeli civilian targets, (most notably in Haifa), were thought to have been supplied by China. Cohen made no promises, but after he met Zhou Enlai in Geneva that year, the button mines ceased to be a hazard.

visualisingchina.net

But the most famous of our agents is Mikhail Borodin, the Comintern representative who led its mission to support the Guomindang in the period of its first alliance with the newly-established Chinese Communist Party in 1923-27. Of course, Borodin was ultimately working in plain sight, and was not averse to giving newspaper interviews. But when he first arrived in the capital of what would become the Nationalist Revolution he did so in a Soviet freighter, shipping south from Shanghai with its cargo of sheep. Here is Borodin, sometime inmate of a Glasgow jail, photographed by Fu Bingchang, with another former jailbird watching. That man is Morris ‘Two-Gun’ Cohen. Cohen, sometime gangster, gun-runner and fixer, who was born in Poland, grew up in Stepney, East London, and had migrated to Canada when he first encountered Sun Yat-sen, whose bodyguard he became. Both men would experience captivity again: Cohen in a Japanese internment camp in Hong Kong, and Borodin in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison, where he died in 1951.

copplestonecastings.co.uk

White Russian Officer in Chinese Army, Two-Gun Cohen (Sun Yatsen`s bodyguard and general assistant), Mikhail Borodin (Soviet agent and organiser) and One-Arm Sutton (supplier and commander of heavy mortars for several Chinese Warlords).

BC20 - European Advisors jewsofchina.org

REVOLUTIONARY ASSOCIATIONSThis year’s month of February marked the centennial of the completion of China’s first revolution of the 20th century: the founding of the Republic of China, the first republic in Asia, by Dr. Sun Yat-sen.

An idealistic revolutionary, Sun (known in China and Taiwan as Sun Zhongshan) believed that for China to become a modern, democratic, progressive country, respected by the world, the declining Qing dynasty founded by the Manchu invaders in 1644 had to be overthrown and replaced by a republican form of government.

But Sun’s concerns for the future of his country ran deeper. Like many Chinese reformers and revolutionaries of his time, he was influenced by the pernicious doctrine of social Darwinism, which viewed the world as an arena of international rivalry and struggle, in which only the fittest among the nations survived.

China had suffered so many humiliating defeats in its confrontations with the West and Japan that it seemed its very survival was in question. This led Sun, among others, to view the historical fate of the Jewish people as a mirror of what might await China: exile and persecution. Sun bemoaned China’s lack of cohesion and his prescription was for them to follow the Jewish example of possessing a firm sense of nationhood.

Sun strongly admired Zionism and, over the years, he had contact and formed relationships with several Jews.

For more than a decade from his places of exile in Japan and North America, Sun led the Kuomintang, the Chinese Nationalist Party that he founded. His followers attempted almost yearly uprisings in coastal cities of China in the hope that any of these could become the spark that would light up the revolutionary conflagration.

In 1908, the empress-dowager Cixi, who for half a century had ruled the empire with an iron hand, died, leaving on the throne an infant emperor and a weak regent.

Three years later, on 10 October, 1911, the garrison of the inland metropolis of Wuchang rose in revolt and revolution spread across the south.

Sun returned to China and was proclaimed president of the Republic of China in the southern capital Nanjing (Nanking). However, the north and Beijing remained firmly under the control of the dynasty and its most powerful army, commanded by the opportunistic general Yuan Shikai, who inflicted defeat on the revolutionaries and then negotiated a settlement: in exchange for Yuan forcing the monarchy to abdicate, Sun would yield the presidency of the republic to him.

Yuan’s next move was to stage a coup and make himself president for life in 1913 and emperor in 1915.

However, Yuan’s death the following year saw China break up into regions ruled by opposing warlords while, in Beijing, a weak government and president maintained a semblance of unity.

Back in Canada, in 1912, the adventurer Moishe (Morris) Cohen, the unruly son of a London East End Gabbai, had been inducted into the membership of the Calgary branch of the Kuomintang by the Chinese friends he had made in the course of his activities, in Saskatchewan and Alberta, activities that landed him in the Prince Albert penitentiary.

Cohen was the only Caucasian to earn that mark of trust, and he had previously won distinction for his bravery and competence as a sergeant in the Edmonton Irish Brigade during the WWI.

After WWI, Cohen embarked on a new life of adventure in China, where he was introduced to Sun, who made him his chief bodyguard.

In 1917, Sun had established a revolutionary government in Canton, from where he hoped to gather forces to fight the northern warlords and finally reunify China under the leadership of the Kuomintang.

In the course of a foiled attempt on Sun’s life, Cohen suffered a wound to his left arm; this inspired him to train himself to shoot from both hands, hence earning the sobriquet, “Two-Gun Cohen.”

Cohen greatly admired Sun, and the Chinese leader’s ascendancy over him seems to have changed him into a well well behaved, moral man. Cohen mourned Sun’s 1925 passing like one grieves for a father. He thereafter served both Sun’s widow and the Kuomintang in various missions, earning an honorary generalship in the process.

In 1922, Sun was driven out of Canton by his warlord ally and found refuge in the French concession of Shanghai. On a previous stay there, Sun had met representatives of the Jewish community, notably N.E.B. Ezra, publisher of the Sephardi Zionist newspaper Israel’s Messenger, and David Rabinovich, publisher of

Nasha Zhizn, the organ of the Russian Jewish community.

In a letter published after the Balfour Declaration in Israel’s Messenger, Sun assured Ezra of his wholehearted support for the Zionist movement, which he identified with China’s struggle for national emancipation.

Grigori Nahumovich Voitinsky, agent of the Communist International (Comintern) organization, was also present in China around that time. In Shanghai since 1920, Voitinsky established relationships with radical young professors and students and persuaded them to found the Chinese Communist Party in 1921.

In 1922, the Comintern adopted a strategy of alliance between European communists and revolutionary nationalists in Asian countries that were colonies (India, Indonesia) or semi colonies like China, in order to break the encirclement of Soviet Russia by Western and Japanese imperialism.

To implement Vladimir Lenin’s “two-stage revolution” theory for Asia (which stated that national liberation and the proletarian socialist revolution could be only achieved following industrialization and the modernization of government), the Comintern dispatched Adolf Abramovich Yoffe to Shanghai.

There, he and Sun crafted a formal agreement known as the Sun-Yoffe Declaration of 1923, whereby the two men agreed that Soviet Russia would provide assistance to China even though it was not ripe for a Soviet- style revolution. No sooner was the agreement signed, than a coalition of minor warlords occupied Canton and invited Sun to return and re-establish a revolutionary government.

At Sun’s request, the Comintern now sent to Canton a most experienced veteran revolutionary, Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg, alias Borodin. Borodin, a native of Riga, had for years been active in leftwing movements in Chicago. He became Sun’s chief advisor.

At Borodin’s urging, Sun reorganized the Kuomintang into a disciplined party following a Leninist model, and created a revolutionary army led by the party, for which Russia provided instructors (chiefly general Vassili Bluecher, alias Galin) and weapons. In addition, Borodin helped Sun to make his ideas more coherent in the form of an ideology based on three principles: nationalism, democracy and people’s livelihood (welfare statism).

Disappointed with the failure of the West and Japan to support his movement, Sun heavily relied on the Soviet alliance. He did, however, resist the more radical suggestions of Borodin, such as confiscating the land of the landlord class.

In May 1925, Sun was invited to Beijing by a coalition of warlords who sought to negotiate for a peaceful reunification of China. Sun died soon after his arrival of lung cancer.

By the following year, the Kuomintang’s revolutionary army undertook its northern expedition to reunify China but, by then, Borodin was bested by the army’s commander, Chiang Kai-shek, who, notwithstanding his graduation from the Moscow military academy, turned by force against his communist allies and expelled Borodin and other Soviet advisors from China.

After establishing his National Government in Nanjing, Chiang claimed Sun’s mantle, and enshrined his predecessor as “Father of the Nation” in an elaborate mausoleum. His government did not, however, pursue

Sun’s pro-Zionist promise: in the United Nations vote of November 1947, which decided on the partition of Palestine, its representative abstained.

China’s consul-general in Vienna did nevertheless save thousands of Jews by issuing visas to China before the war broke out.

Jewish Times Asia –April 2012 |