New SPAC Stuff Keeps Imploding amid Shortage of “Consensual Hallucination,” as I Call it, But Now the Imploding is a Lot Faster

by Wolf Richter • Dec 6, 2022 • 13 Comments

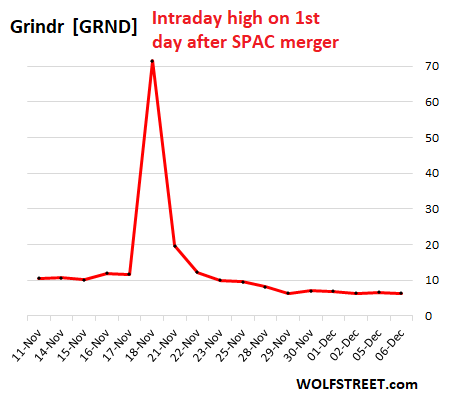

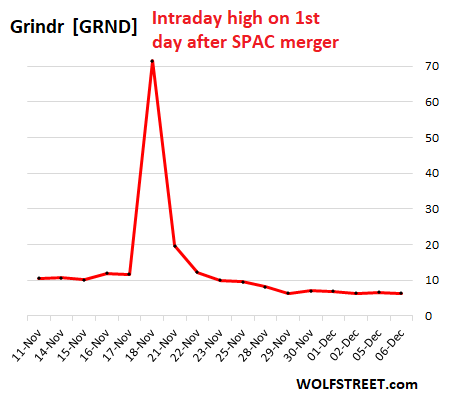

I mean, like within hours and days, rather than weeks and months. But the SPAC sponsors want make some money.By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.Grindr, which describes itself as “the world’s largest social network for the LGBTQ community,” went public via merger with a SPAC on November 18, 2022. On that first day as a public company, the shares shot from the price of the pre-merger-SPAC of $11.63 to an intraday high of $71.51, at which point the collapse started, and 7 trading days into it, the shares had kathoomphed by 91% from that high, and today, 12 trading days into, they’re still down 91%, at $6.37. This chart is just nuts:

SPAC sponsors – often private-equity firms, venture-capital firms, or wealthy people – want to make some money. But they will only make money if the SPAC merges with a target company because when the merger closes, they typically get 20% or so of the funds raised in the IPO of the SPAC. After the SPAC’s shares trade under the ticker of the acquired company, and crash, well, the sponsors already got their 20% out.

But if that SPAC cannot merge with a target company by the time the two-year deadline comes around, it has to shut down and return the money raised in the IPO to the SPAC’s shareholders. At that point, the sponsors won’t get their 20% of the funds raised. Plus, they will lose the startup capital that they put into the blank-check company and that was used to pay underwriters, lawyers, registration fees, etc. on the way to the IPO to become a publicly traded SPAC.

That’s the tradeoff: If the SPAC completes a merger with a zombie, and starts trading under the zombie’s ticker, the sponsors make a ton of money even if the shares collapse. But if a merger cannot take place by the two-year deadline, the sponsors are out their startup capital. So you can figure how that motivates the sponsors.

In the three years of 2020 through 2022, a total of 944 SPACs were formed and went public via IPO in the US, according to the count by SPAC Research, raising money that way to be used to acquire a real company which would then become the publicly traded company.

It might seem that 944 merger targets would be a lot of companies to acquire and turn into publicly traded stocks. But hey, it was the era of consensual hallucination, and everything flew, everyone went along, money was falling from the sky, and a mad scramble ensued to line up celebrities of all kinds to promote this stuff, and when this stuff then collapsed, some of them got sued.

But the time-frame of that collapse is getting much shorter.Grindr’s implosion started within hours of it as a public company, and took it down by 91% in seven days. Grindr has revenues, but not a lot, just $50 million last quarter. And it had a net loss of $4.8 million in the quarter, according to its first preliminary financial results released yesterday. This is a smallish company that has been around since 2009, and it’s losing money.

When the SPAC deal was announced in May 2022, it was done at a ridiculous $2.1 billion valuation that would require a huge amount of consensual hallucination to pull off.

But consensual hallucination has been fading, though it hasn’t faded nearly enough yet, and the shares plunged, but at $6.37, they’re still giving the company a ridiculous market capitalization of $1.1 billion.

On November 16, the SPAC’s shareholders approved the merger, and it was off to the races. But about 27.1 million shareholders of the original SPAC, or about 98.2% of the shareholders, voted to redeem their shares, and they’ll get a little over $10 a share (original IPO price of the SPAC plus some interest). They didn’t want to hold those shares when they started trading as Grindr.

This left Grindr, when it actually started trading, with a very small float of about 500,000 shares, and it left it with nearly none of the cash that it would have received if 98.2% of the shareholders of the SPAC hadn’t asked for their money back.

Essential financial details remain fuzzy; they weren’t reported in the preliminary results document released yesterday, such as how much cash the company actually has post-merger, and how it would pay down its $137 million in existing debts, etc., etc. Because this wasn’t an IPO, this was a SPAC merger, and the disclosure requirements are minimal, and the promises made are huge, and you end up with whatever.

But what else can SPAC sponsors do?Sponsors can shut down the SPAC and return the money raised in the IPO to the shareholders, if they cannot find an acquisition target within the deadline – rather than scrambling to buy whatever at whatever price. But then the sponsors are out the startup capital they plowed into the SPAC. And this is now happening a lot.

For example, Altimeter Capital, a venture capital fund, announced on December 1 that it would dissolve its SPAC #2, the Altimeter Growth 2 Corp [ AGCB]. The SPAC had a deadline of January 11, 2023, to find a merger target. But it’s tough amid this shortage of consensual hallucination, with stuff imploding left and right. So it pulled the ripcord.

The SPAC’s shares [AGCB] are trading at $10.07, which is near the IPO price of $10. The company will redeem all of the outstanding shares at the per-share redemption price of $10.11 paid for with funds in the trust account.

Altimeter Capital has already become infamous. Its SPAC #1, Altimeter Growth Corp, had acquired SoftBank-backed Grab, the largest ride-hailing and food-delivery app in Southeast Asia. The merger, announced in April 2021 and approved by SPAC shareholders on November 30, 2021, valued the company at $40 billion, making it the biggest SPAC deal ever. The shares started trading under the new ticker [ GRAB] on December 2, 2021. And promptly collapsed.

This was further aided on March 3, when Grab reported earnings for the first time as a publicly traded company: a monstrous loss of $1.06 billion for Q4, and of $3.45 billion for the year, on top of a loss of $2.61 billion in the prior year – for a total loss of $6.1 billion in two years. I suspect that no SPAC had ever produced so much red ink in such a short time. Shares kathoomphed 37% on the spot, and by 81% from the intraday high four months earlier, and I honored Grab with an official spot in my pantheon of Imploded Stocks.

SPAC dissolutions abound.So far this year, about 100 SPACs have thrown in the towel on a possible merger. Of them, 60 SPACs redeemed the shares and dissolved, and about 40 have started the dissolution process, according to a report by SPAC Research. Another 40 have year-end deadlines, and they may seek deal extensions from their shareholders or shut down.

Two of the SPACs being dissolved are creatures of busted “SPAC King” Chamath Palihapitiya, whose venture firm, Social Capital, had put together six SPACs. The other four merged with companies and their shares collapsed:

Opendoor Technologies [ OPEN], house flipper: $1.41 (-96% from high).Clover Health Investments [ CLOV]: $1.19 (-96% from high).SoFi Technologies [ SOFI] online student-loan lender that pivoted to stock & crypto platform: $4.32 (-85% from high)Virgin Galactic [ SPCE], dreaming of space-tourism: $4.62 (-93% from high).Palihapitiya’s firm, as sponsor, made a ton of money on those four SPACs that merged with Opendoor, Clover Health, SoFi, and Virgin Galactic, though shareholders got ransacked. The two SPACs where Palihapitiya’s firm lost money were those that are being dissolved — and where shareholders didn’t lose money.

Enjoy reading WOLF STREET and want to support it? You can donate. I appreciate it immensely. Click on the beer and iced-tea mug to find out how:

|