Amazon’s Injury-Plagued Warehouse Operation Goes on Trial

Hearings in Washington state starting in late July will usher in a period of broader government scrutiny of the e-commerce giant.

By Spencer Soper, and Josh Eidelson

Bloomberg

July 24, 2023 at 6:00 AM EDT

Amazon’s BFI4 fulfillment center in Kent, Washington, where state inspectors strapped ergonomic monitors to workers. / Photographer: Chona Kasinger/Bloomberg

--------------

In December 2021 a doctor and an occupational health expert entered Amazon.com Inc.’s mammoth BF14 fulfillment center in Kent, Washington, about 20 miles south of the company’s Seattle headquarters. They were there at the behest of state regulators to investigate why workers at the world’s largest online retailerare injured more often than their counterparts in warehouses that other companies run.

Echoing Amazon’s penchant for tracking employees’ every move, the investigators used electronic monitors and video cameras to measure the stooping, lifting, reaching and twisting required to pick, pack and ship products to customers across the US. Over three days they observed more than 50 employees performing 12 tasks, including unloading trucks stacked floor-to-ceiling with boxes weighing as much as 50 pounds, packing customer items in envelopes and moving around pallets of products on rolling jacks.

Packages ready for shipment move along a conveyor belt at the fulfillment center in Kent.Photographer: Chona Kasinger/Bloomberg

-------------------------------

The inspection—done with a court order because Amazon initially refused the use of electronic monitors—found hazards in almost every task reviewed. Ten-hour shifts with mandatory overtime and a rapid work pace put workers at risk of hurting their backs, shoulders, wrists and knees, the investigators determined. Employees surveyed by the inspectors said pushing through pain was the norm, with some 40% saying they’d experienced it in the previous seven days. Of those, two-thirds said they took medication to ease symptoms.

These findings will be front and center starting in late July as Washington’s Board of Industrial Insurance Appeals begins considering citations the state issued against Amazon, which the company is contesting. The state Department of Labor and Industry says Amazon pushes workers too hard by setting onerous performance targets that inevitably get people hurt. Last year, on average, 100 Amazon warehouse workers were injured each day in the US—out of a workforce of about 750,000—and required about two months to recover, according to a Bloomberg analysis of federal injury data.

The Washington hearings are just the beginning of a widening government crackdown on Amazon’s safety record that’s arguably the most intrusive scrutiny in the company’s history. After inspecting six warehouses in five states, federal regulators earlier this year cited Amazon for exposing workers to a range of musculoskeletal maladies and for failing to provide adequate medical treatment. Amazon is appealing the citations even as the government conducts further investigations. California, New York, Minnesota and several other states have passed or are considering new laws crafted to help prevent industry productivity quotas from interfering with legally required meal and rest breaks.

It’s not an exaggeration to say Amazon’s business model is on trial. For years the company has managed to stay one step ahead of rivals with its one- or two-day delivery guarantee. If regulators have their way, Amazon could be forced to hire more workers and make its operations more ergonomically sound—remedies that would raise costs at a time when online sales growth has slowed and the company is focused on boosting profits. The retail giant says its safety record is improving and has pledged to continue working on it, but Amazon still exceeded warehouse industry injury rates from 2018 to 2021, federal data and company records reveal.

“This is an indictment by authoritative expert public agencies that the company has completely mishandled the design and operation of its warehouses, and it’s causing a crisis,” Eric Frumin, the health and safety director at the pro-union Strategic Organizing Center, says of the mounting pressure on Amazon. “It’s a very powerful rebuke of the company’s public posture.”

In a statement, Amazon spokesperson Maureen Lynch Vogel said the company looked forward to showing that the state’s allegations “are inaccurate and don’t reflect the reality of safety at Amazon.” She said the company’s investments in safety are paying off and that “recordable injury rates” at the Kent warehouse have fallen 16% since 2018 and 40% at another facility in DuPont, Washington. “We’re proud of our progress, and we’ll continue working to get better every day,” Lynch Vogel said.

Over the past 20 years, Amazon has revolutionized the way people shop, creating a vast online catalog of goods that can be delivered within a day or two. Increasingly, it’s trying to deliver customers’ orders the same day they’re placed, making shopping online comparable to a quick run to a nearby store. To achieve this, the company has built hundreds of warehouses across the US and staffed them with hundreds of thousands of workers, making it the country’s second-largest private employer, behind Walmart Inc.

Amazon has automated some of the more laborious parts of its operation. Robots can now bring products to workers so they don’t have to trek 15 miles or more per shift pushing heavy carts. Despite help from machines, employees are still hauling around pallet jacks carrying 1,400 pounds of kitty litter, unloading trucks filled with 40-pound dumbbells and hoisting heavy car parts such as brake rotors and batteries, according to the Washington state investigation. Rival logistics companies and retailers are copying Amazon’s practices, giving regulators further impetus to crack down.

A worker sorts merchandise at an Amazon fulfillment center in Robbinsville, New Jersey.Photographer: Michael Nagle/Bloomberg

------------------------------------------

There are no specific federal legal standards for workplace ergonomic safety in the US. Washington state’s Labor Department and former US President Bill Clinton’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) both enacted such rules two decades ago, but they were reversed by voters and former President George W. Bush, respectively. Since then, under federal law, bringing an ergonomics case has required proving a company fell short of its more general obligation to protect staff from “recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm.” As a result, Amazon inhabits a legal gray area that gives it discretion over how hard to push workers.

\The company maintains that warehouse employees are subject to “comfortable and reasonable” productivity quotas. Amazon has also pledged to make its warehouses safer. Chief Executive Officer Andy Jassy made injury reduction a central part of his inaugural letter to shareholders in 2022, following a pledge from predecessor Jeff Bezos to make Amazon “Earth’s safest place to work.” The company coaches workers to lift with their legs, stocks warehouse vending machines with pain medication and encourages personnel to stretch. Amazon’s injury rate in 2022 was lower than a year earlier; industry averages for comparison purposes won’t be released by the US Department of Labor for several months.

The Washington state crackdown began after Amazon employees complained to officials about working conditions, and the Center for Investigative Reporting published an report that included details about injuries at a Washington warehouse. State inspectors first went to a facility in DuPont, south of Tacoma. They collected video but were asked to leave after trying to put electronic monitors on workers. The investigators had hoped to evaluate 11 jobs but were able to collect sufficient data on only 3. They found all of them to be hazardous.

A few months later, armed with the court order, they strapped monitors to workers at the Kent warehouse. One device, a Lumbar Motion Monitor developed by the Spine Research Institute at the Ohio State University, assessed the risk of lower back injuries. Investigators also used motion sensors from the Dutch company Xsens Technologies that target the torso, head, arms and legs, to measure risks associated with stooping, twisting and repetitive hand and arm motions. Risks included workers having to reach high above their head to get boxes, repeated lifting, and twisting and gripping.

The investigators used a “composite lifting index” to calculate the injury risk of different jobs by measuring the frequency of lifts, the weight of items, the height the items are lifted and the length of time a worker does this kind of work during a shift. Of six jobs evaluated, four exceeded the lifting frequency for the risk model, meaning they required “immediate attention.” The riskiest roles included “destuffers,” who unload boxes from trucks, and “fluid loaders,” who place outbound packages onto trucks from chutes. The destuffers would face significant back injury risk even if they performed that task for only one hour each day because of the rapid pace of work, investigators found. Workers measured performed 840 lifts per hour, and one-third of the packages lifted weighed 25 pounds to 50 pounds.

Workers prepare orders for shipment at Amazon’s fulfillment center in Kent.Photographer: Chona Kasinger/Bloomberg

--------------------------------------------

The federal government has taken a growing interest in Amazon warehouse injuries as well. Starting last year, OSHA inspected warehouses in Colorado, Florida, Idaho, Illinois and New York. In February the agency cited Amazon and delivered hazard alert letters for exposing employees to ergonomic risks that include frequent lifting of heavy items over long shifts at facilities in Aurora, Colorado; Nampa, Idaho; and Castleton, New York, near Albany. OSHA proposed $46,875 in penalties, a tiny sum for a company of Amazon’s size, but the sweeping investigation shows federal officials are worried about systemic problems and not only scattershot mismanagement.

OSHA earlier cited Amazon for violations at facilities in Florida, Illinois and New York. The agency found elevated injury risks at all six warehouses it inspected. The facilities investigated by the federal government and Washington state officials are among the company’s most dangerous in the country, according to federal workplace injury data. “We disagree with OSHA’s characterization of safety at our sites, and we are appealing the citations,” Lynch Vogel said regarding the federal agency’s findings. “Importantly, neither pace of work nor shift duration were noted as alleged causal factors of injuries, nor did federal OSHA mention changes to them as recommended abatement measures.”

Meanwhile, Amazon warehouse workers have traveled to several state capitals and testified before lawmakers. In a January hearing of the Minnesota Senate Labor Committee, Mohamed Hassan, who worked at a company facility, described being injured three times in seven years. Speaking through an interpreter, Hassan said he was constantly twisting, turning and bending “like a robot.” Minnesota in May passed a bill that would direct the state to investigate companies with injury rates 30% higher than those of industry peers, among other things.

The BFI4 fulfillment center in Kent.Photographer: Chona Kasinger/Bloomberg

--------------------------------

In March an Amazon warehouse worker told Connecticut lawmakers he was expected to pack 200 boxes an hour. “I’m a little embarrassed to say I’m one of those people that loves to get their Amazon box the next day or even the very same day,” state Senator Julie Kushner, a Democrat, said at the end of the hearing. “Now that I hear someone had to pack 200 boxes in an hour, it makes me feel pretty guilty.” Connecticut is considering a bill similar to those passed in California, New York, Minnesota and Washington. At least 10 other states are also mulling such legislation.

“These bills are constructed based on a misunderstanding of our business performance metrics,” Lynch Vogel said. “Amazon does not have fixed quotas at our facilities.

Instead, we assess performance based on safe and achievable expectations and take into account time and tenure, peer performance and adherence to safe work practices. While we know we aren’t perfect, we are committed to continuous improvement when it comes to communicating with and listening to our employees and providing them with the resources they need to be successful.”

The Washington hearings will play out over several weeks. The state will present its case, and then Amazon will call its own witnesses, including warehouse employees and ergonomic experts, to make its case that Amazon’s warehouses are safe and the state’s requests are costly and onerous. Amazon officials have said the cost of retrofitting one warehouse with the state’s recommendations would cost millions of dollars and is likely to disrupt its operations. The Bureau of Industrial Insurance Appeals serves as a courtlike arbiter in disputes between the state’s Labor Department and employers. If it upholds the state’s findings, Amazon can appeal them through the state court system and potentially delay any remedies for years.

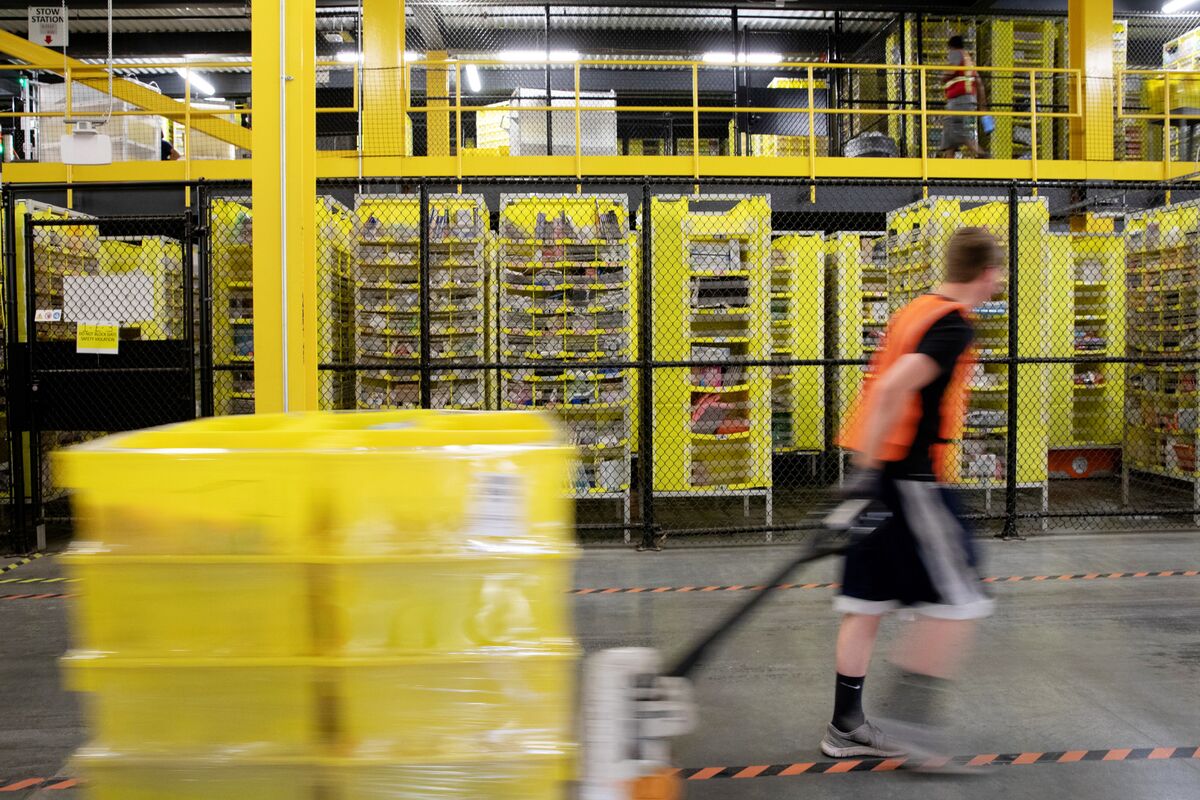

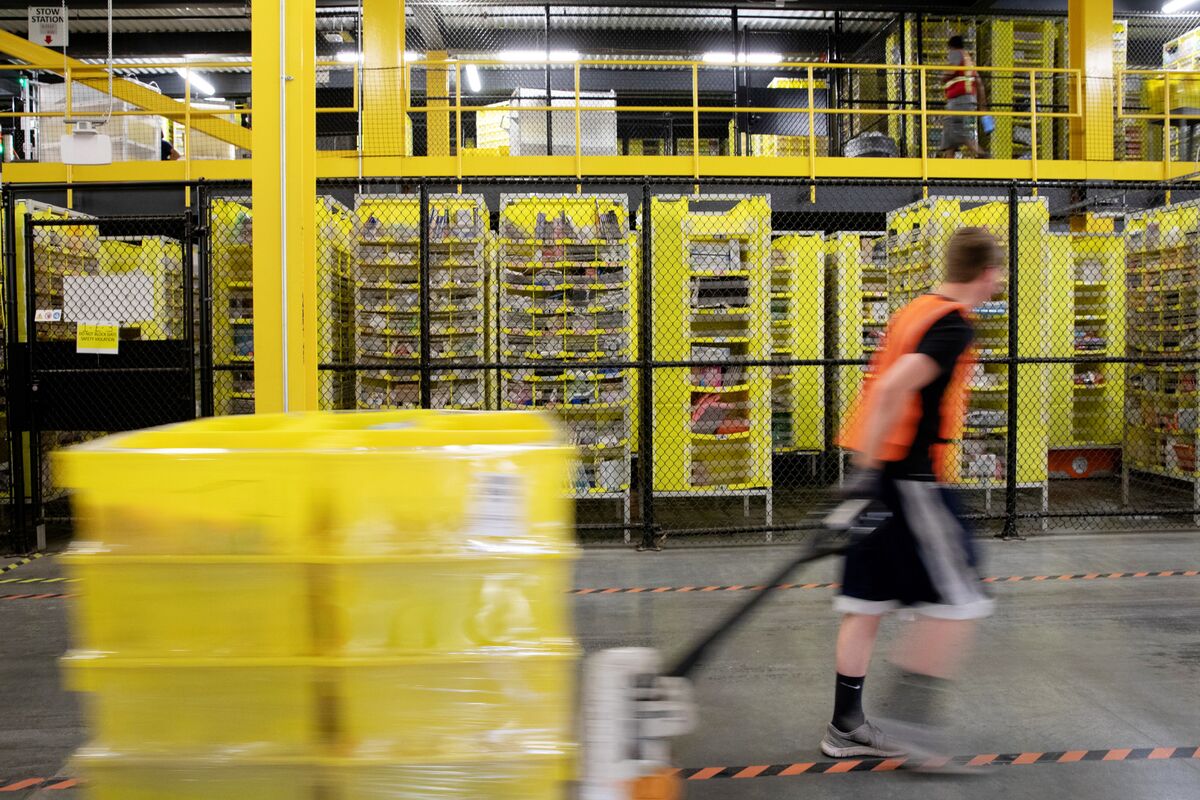

An employee pulls a pallet jack at Amazon’s fulfillment center in Robbinsville.Photographer: Bess Adler/Bloomberg

-----------------------

In the meantime, Washington officials are urging the company to purchase common industrial equipment such as motorized pallet jacks and spring-activated carts, which can ease the toll on a worker’s body. Such an investment for Amazon’s entire logistics network would probably cost $500 million or more but would save money in the long run by reducing expenses associated with injuries, says Richard O’Connor, the director of warehouse safety equipment maker First Mats, who reviewed the state’s recommendations for Bloomberg Businessweek.

Ergonomist Rick Goggins, who’s spent 28 years at Washington’s Labor Department, says he and his colleagues want Amazon to thrive because it’s the state’s largest private employer. “But I want to make sure that workers aren’t getting injured as part of that success,” he says.

Amazon Warehouse and Worker Safety Probed by Washington State - Bloomberg (archive.ph) |