| | | The Middle Ages’ Ultimate Sign of Loyalty

A grisly amputation hints at why Europeans once had so much reverence for rulers’ feet.

By Jack Hartnell

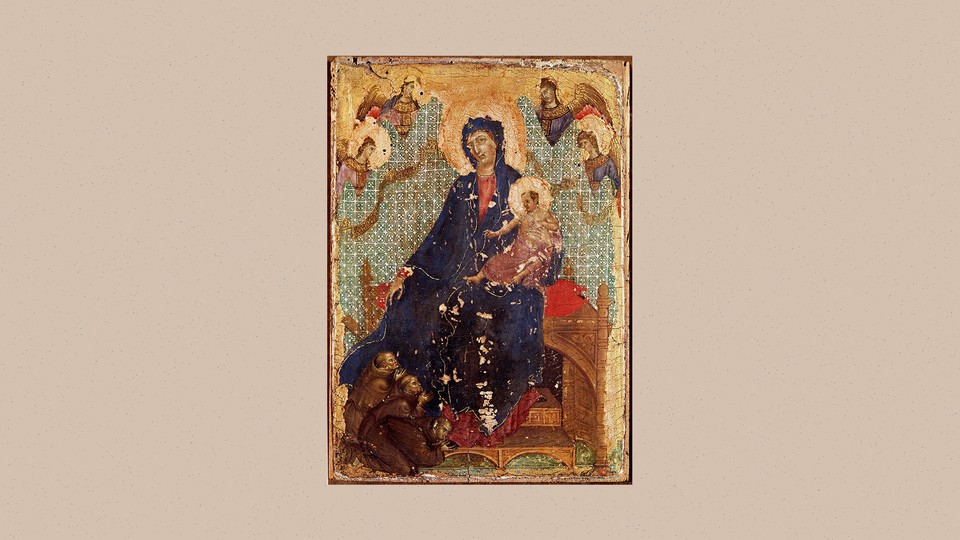

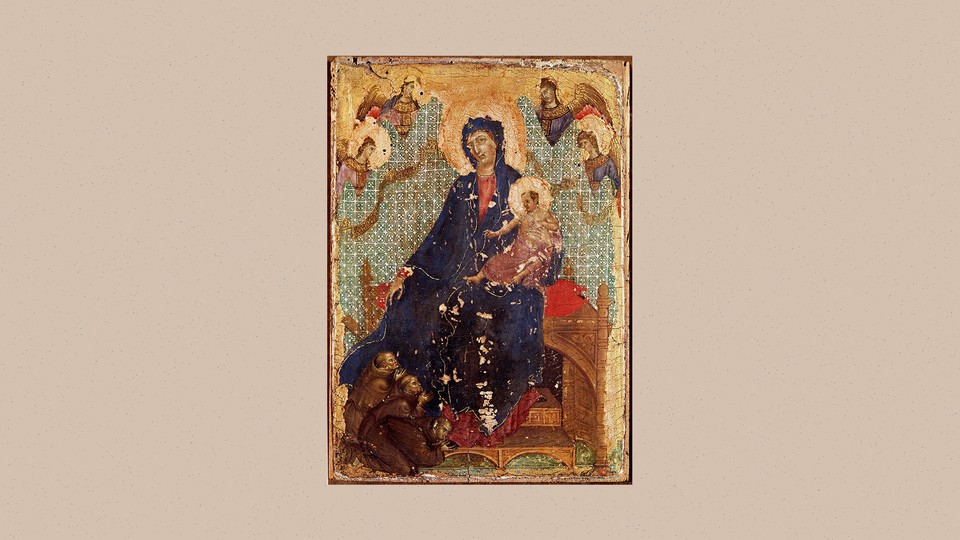

Italian artist Duccio di Buoninsegna painted the Madonna dei Francescani in the 1280s. (Leemage / UIG via Getty / The Atlantic)

By the middle of 1493, the Holy Roman Emperor Friedrich III’s left foot had turned almost completely black. His doctors had begun to worry some weeks earlier, when it first started slowly shifting from a healthy pink toward a shade of darkened blue. The late medieval compendia to which they might have turned for guidance spent little time on this final extremity of the body, only really discussing what to do in the case of surface issues such as boils, blisters, or swellings. So without further instruction, the doctors were left to think instinctively.

Some declared Friedrich was lacking humoral warmth and should be prescribed fiery medicaments to remedy the situation. Others insisted that the malady was down to the emperor’s near-constant consumption of melons, in which he apparently took excessive pleasure. Either way, something had to be done.

This post was excerpted from Hartnell’s upcoming book.

A coterie of medics converged on the Austrian city of Linz, where the emperor was attempting to recover. Friedrich’s son, the future Emperor Maximilian, sent his Portuguese physician, Matteo Lupi. The monarch’s brother-in-law, Duke Albrecht IV of Bayern-München, sent the renowned surgeon Hans Seyff to Friedrich’s bedside. And they were joined there by four more German physicians who had been summoned: Heinrich von Cologne, Heinz Pflaundorfer von Landshut, Erhard von Graz, and Friedrich von Olmutz. After mulling over the emperor, the learned group decided reluctantly that his worsening foot necessitated medieval medicine’s last resort: amputation.

What followed cannot have been pleasant. While some anesthetic would probably have been made available to Friedrich—numbing plants and opiates, hemlock, poppy or meadowsweet, applied to a sponge or burned for inhalation—pain relief in the Middle Ages was minimal and not particularly effective.

As the five physicians steadied Friedrich, Seyff and another surgeon, Larius von Passau, cut through the leg above the affected area, severing skin and soft flesh with sharp knives before sawing through what remained in order to remove the foot. They then applied powders to stanch the bleeding and bandages to keep the wound as clean as possible. Though one hopes the procedure was quick, it is hard to believe he underwent it with quite the grace shown in an image of the operation preserved in a manuscript in Vienna. There, Friedrich appears blank-faced and in a mood of drooping calm, sitting relaxed and stretched wide in Christ-like repose as the surgeons work away at the coal-black foot. The attending physicians are shown behind him daintily supporting his arms, although they were far more likely to have been pinning the struggling emperor down as the saw’s teeth worked their way through skin and muscle to the bone. |

|