If needed I will certainly do this and it looks like we are going 2

APRIL 22, 2024

Editors' notes

Common antibiotic may be helpful in fighting respiratory viral infections by Jim Shelton, Yale University

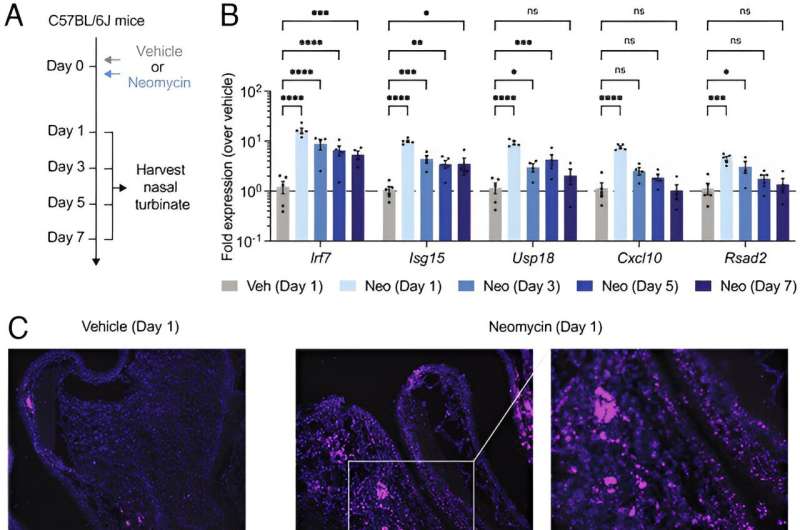

Intranasal application of neomycin induces an upper respiratory ISG response independent of commensal microbiota. Credit: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2319566121

A new, Yale-led study suggests that a range of respiratory viral infections—including COVID-19 and influenza—may be preventable or treatable with a generic antibiotic that is delivered to the nasal passageway.

A team led by Yale's Akiko Iwasaki and former Yale researcher Charles Dela Cruz successfully tested the effectiveness of neomycin, a common antibiotic, to prevent or treat respiratory viral infections in animal models when given to the animals via the nose. The team then found that the same nasal approach—this time applying the over-the-counter ointment Neosporin—also triggers a swift immune response by interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) in the noses of healthy humans.

The findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"This is an exciting finding, that a cheap over-the-counter antibiotic ointment can stimulate the human body to activate an antiviral response," said Iwasaki, the Sterling Professor of Immunobiology and professor of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine and co-senior author of the new study.

"Our work supports both preventative and therapeutic actions of neomycin against viral diseases in animal models, and shows effective blocking of infection and transmission," said Iwasaki, who is also professor of molecular, cellular, and developmental biology in Yale's Faculty of Arts and Sciences, professor of epidemiology at Yale School of Public Health, and an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Respiratory viruses affect millions of people each year. The global COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, has led to 774.5 million cases worldwide as of February 2024, with global mortality of 6.9 million people. Influenza viruses account for up to 5 million cases of severe illness and 500,000 deaths annually worldwide.

Currently, most therapies used to fight respiratory viral infections—including antivirals, monoclonal antibodies, and convalescent plasma therapy—are delivered intravenously or orally. They focus on stopping the progression of existing infections.

A nasal-centered therapy has a much better chance of stopping infections before they can spread to the lower respiratory tract and cause severe diseases, the researchers said.

"This collaborative multi-disciplinary work combined important insights from animal pulmonary infection modeling experiments with human study evaluation of this intranasal approach to stimulate antiviral immunity," said Dela Cruz, former associate professor of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine, and of microbial pathogenesis at Yale School of Medicine and former director of the Center for Pulmonary Infection Research and Treatment. Dela Cruz is currently at the University of Pittsburgh.

In their study, the researchers found that mice treated intranasally with neomycin showed a robust ISG line of defense against both SARS-CoV-2 and a highly virulent strain of influenza A virus. The researchers also found that an intranasal treatment of neomycin strongly mitigated contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in hamsters.

In healthy humans, intranasal application of Neosporin (containing neomycin) also initiated a strong expression of ISGs in a subset of volunteers, the researchers said.

"Our findings suggest that we might be able to optimize this cheap and generic antibiotic to prevent viral diseases and their spread in human populations, especially in global communities with limited resources," Iwasaki said. "This approach, because it is host-directed, should work no matter what the virus is."

The co-first authors of the new study, all from Yale, are Tianyang Mao, Jooyoung Kim, and Mario Peña-Hernández.

More information: Tianyang Mao et al, Intranasal neomycin evokes broad-spectrum antiviral immunity in the upper respiratory tract, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2319566121

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Provided by Yale University

--------------------------------------------------------

Deforestation pushes animals in Uganda forest to eat virus-laden bat poo

2 days ago

By Wedaeli Chibelushi & Natasha Booty,BBC News

Share

Getty Images Getty Images

Chimpanzees, antelopes and monkeys were among the creatures found to be eating bat pooAnimals in a Ugandan forest have been eating bat poo laden with viruses after tobacco farming wiped out their usual food source, a study has found.

A virus linked to Covid-19 was among the 27 identified in the poo eaten by chimpanzees, antelopes and monkeys.

Researchers say this finding sheds light on how new viruses might spread from wildlife to humans.

The animals were monitored in a study by the University of Stirling and the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The six-year project was prompted when Dr Pawel Fedurek from the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Scotland's University of Stirling observed wild chimpanzees in Budongo forest eating accumulated bat excrement, known as guano, from the hollow of a tree.

In July 2017, he set up cameras which captured other species also eating the poo.

According to the peer-reviewed study, which features in the journal, Communications Biology, guano is an "alternative source of crucial minerals" for the animals after the the palm trees they once consumed were "harvested to extinction".

The trees were used by locals in Budongo to dry tobacco leaves, which were then sold to international companies.

For just over six months, researchers collected samples of guano from the tree hollow the animals were filmed eating from.

Lab analysis of the poo identified several viruses, including one related to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that caused the Covid-19 pandemic.

"It remains unknown whether the betacoronavirus found in the guano is transmissible to humans, but it does offer an example of how new infections might jump species barriers," a press release from the University of Stirling said.

"About a quarter the 27 viruses we identified were viruses of mammals - the rest were viruses of insects and other invertebrates," Prof Tony Goldberg, from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in the US, told the BBC.

"All 27 viruses were new to science, so we don't know what effects they might have on humans or other animals. But one virus stood out because is was a relative of a virus everyone knows: SARS coronavirus 2."

ADVERTISEMENT

Dr Pawel Fedurek, an expert in animal behaviour at the University of Stirling, said: "Our research illustrates how a subtle form of selective deforestation, ultimately driven by a global demand for tobacco, can expose wildlife and, by extension, humans to viruses residing in bat guano, increasing virus spillover risk.

"Studies like ours shed light on the triggers and pathways of both wildlife-to-wildlife and wildlife-to-human virus transmission, ultimately improving our abilities to prevent outbreaks and pandemics in the future."

The researchers hope their findings make it possible to intervene in the transmission of viruses between species and ultimately help to prevent future pandemics.

Amazon under threat: Fires, loggers an

|

Getty Images

Getty Images