from the "I did not know" file

scmp.com

Women in China spread secret, female-only language nushu – it’s a bond of sisterhood

Published: 11:15am, 4 Aug 2024

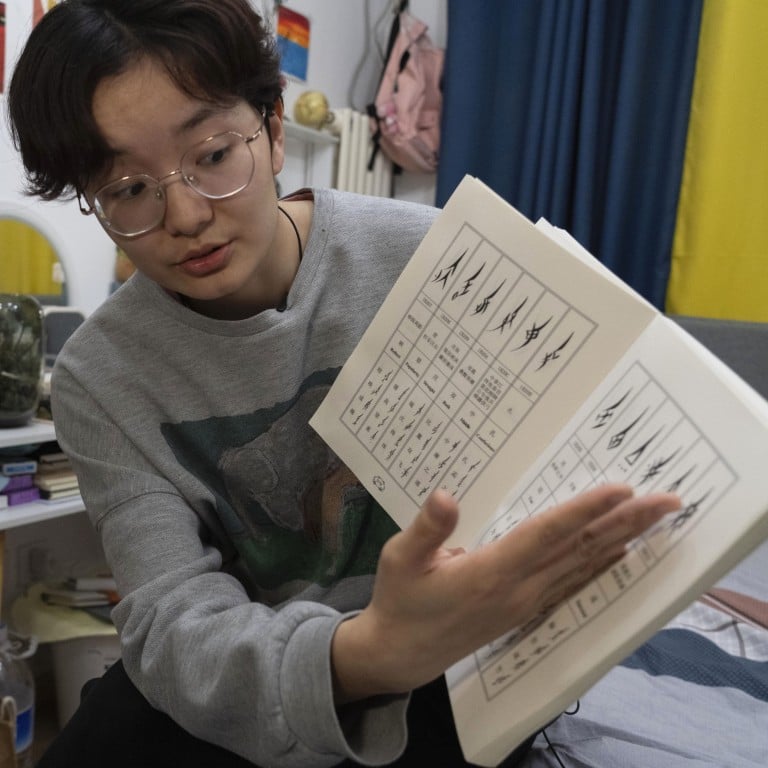

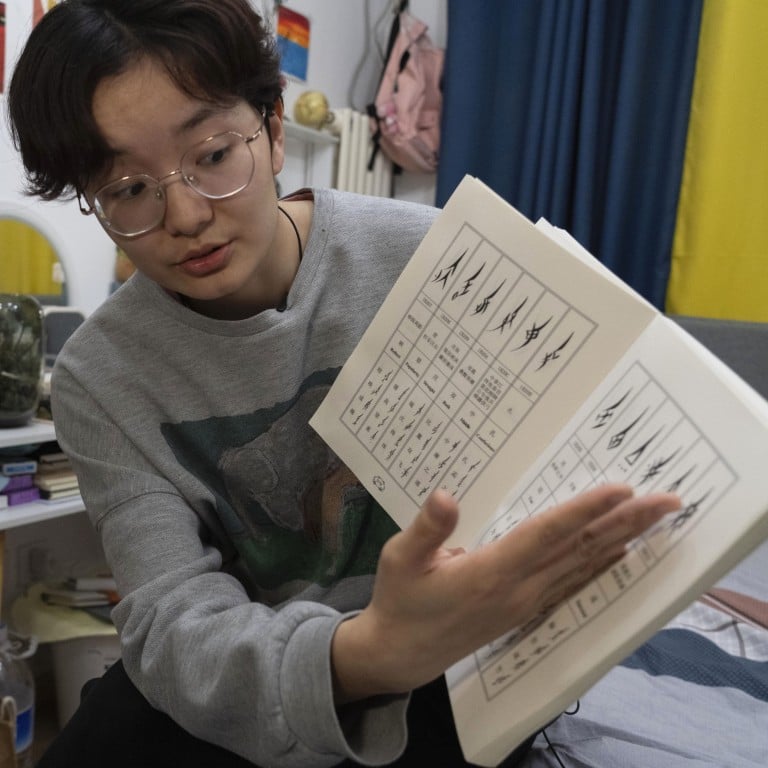

Lu Sirui talks about nushu, a centuries-old secret script which is empowering young women in China even today. Photo: AP

Chen Yulu never thought her home province of Hunan had any culture that she would be proud of, much less become an ambassador of.

But these days, the 23-year-old is a self-proclaimed ambassador of nushu, a script once known only to a small number of women in central China.

It started as a writing practised in secrecy by women who were barred from formal education in Chinese. Now young people like Chen are spreading nushu beyond the women’s quarters of houses in Hunan’s rural Jiangyong county, whose distinct dialect serves as the script’s verbal component.

Today, nushu can be found in independent bookstores across the country, transport advertisements, craft fair booths, tattoos, art and even everyday items like hair clips.

Visitors at a bookstore in Chengdu, southwest China, specialising in nushu. Photo: AP

Nushu was created by women from a small village in Jiangyong, in the south-central province where late Chinese leader Mao Zedong was born, but there is little consensus on when it originated. Scholars estimate the script is at least several centuries old, from a time when reading and writing were deemed male-only activities. The women developed their own script to communicate with each other.

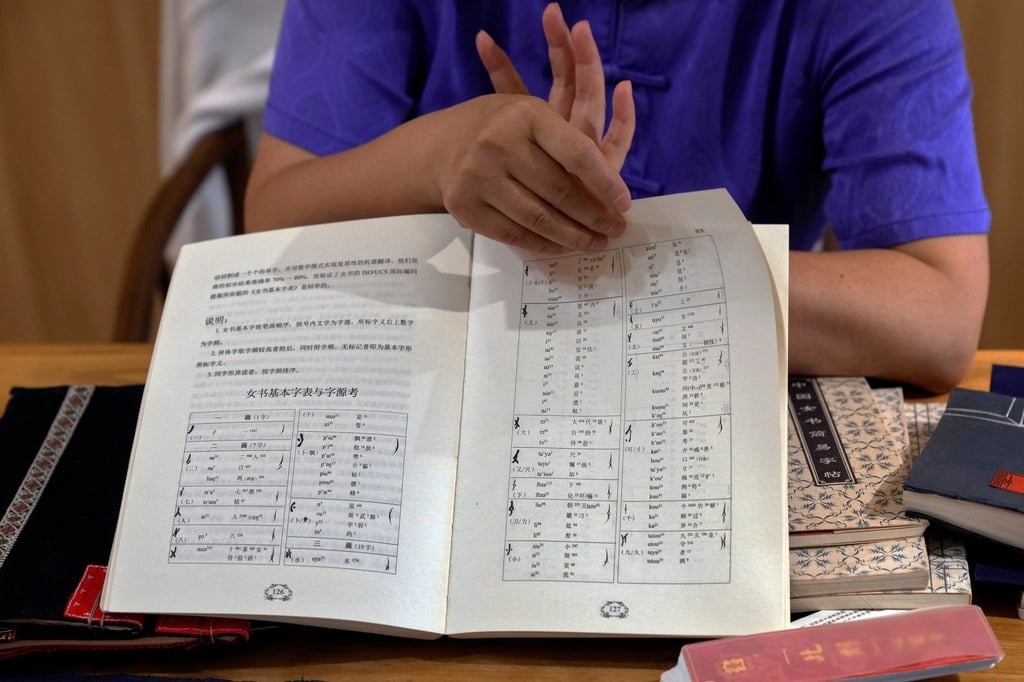

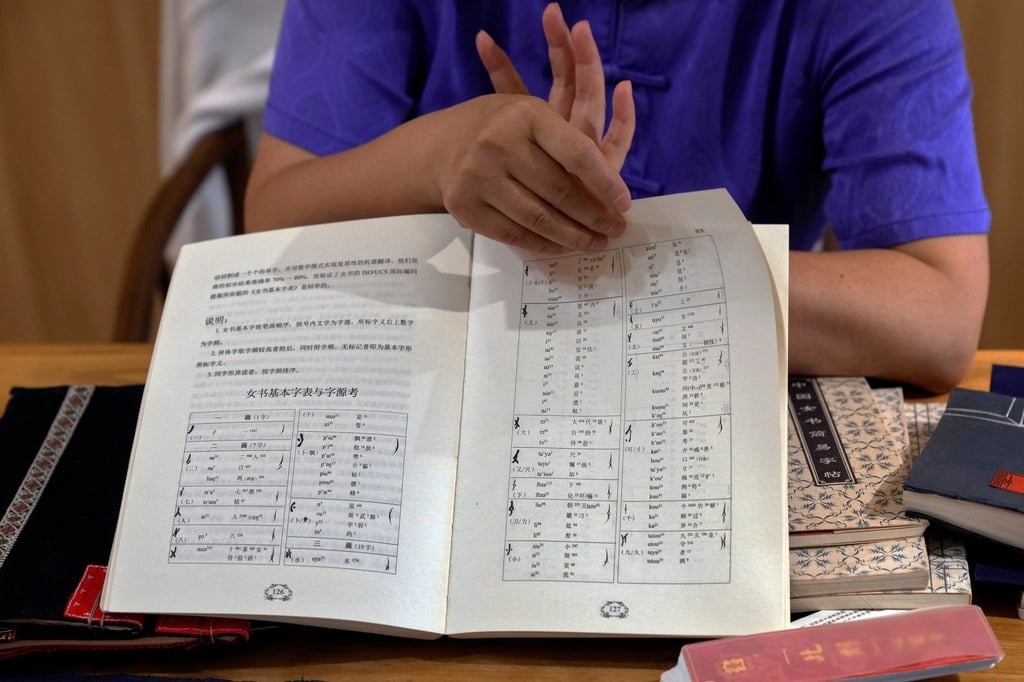

The script is slight with gently curving characters, written with a diagonal slant that takes up much less space than boxy modern Chinese with its harsh angles.

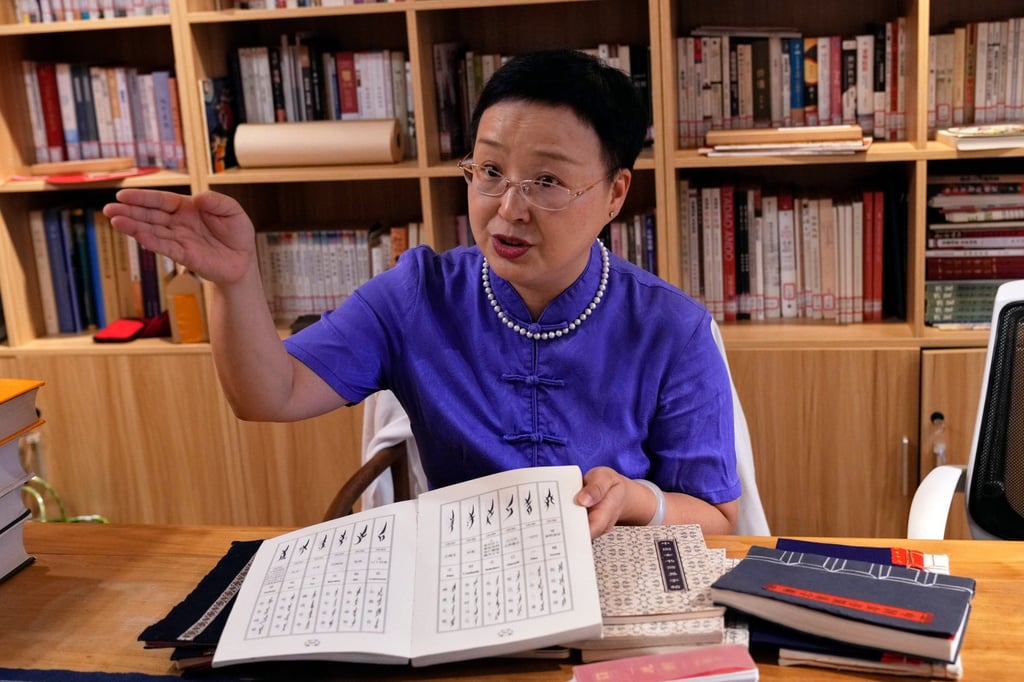

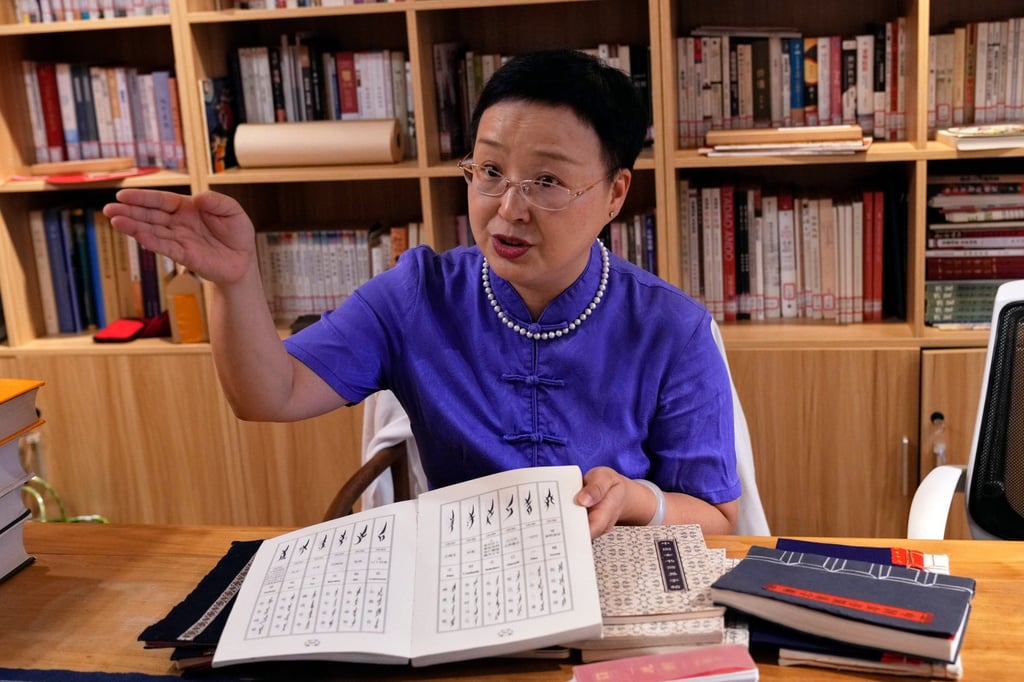

Xu Yan, an author of a textbook on nushu, writes nushu on paper cuttings at her studio in Beijing. Photo: AP

“You won’t allow me to go to school. OK, I get it. So what’s my way out? I’ll find ways to educate myself,” said Xu Yan, 55, the author of a textbook on nushu.

Women lived under the control of either their parents or their husband, and used nushu, sometimes called “script of tears”, in secret to record their sorrows: unhappy marriages, family conflicts, and longing for sisters and daughters who married and could not return in the restrictive society.

Xu is also the founder of Third Day Letter, a nushu studio in Beijing named after a centuries-old practice of the script’s practitioners. The third-day letter is a hand-sewn book presented in farewell to a woman in Jiangyong on the third day after her marriage, when she is allowed to visit the childhood home she left.

Discover news and insights on women trailblazers, social issues and gender diversity in Asia

The script became a unique vehicle for composing stories about women’s lives, typically in the form of seven-character line poems that are sung. A secret world sprang from the script that gave Jiangyong women a voice through which they found friends and solace.

That secret world still resonates today as a source of strength for young women dissatisfied with patriarchal constraints.

Xu shows a book of nushu calligraphy to visiting students at her studio. Photo: AP

Chen, who studied photography at an art school in Shanghai, said her male professors often doubted that she could keep up with the male photographers because of her slight physique. That attitude, she said, is “in every aspect of life, there’s nowhere it doesn’t touch”.

She was frustrated but did not see much room to retaliate – until she learned about nushu.

“I felt that I had received a very strong power, and I think a lot of women need this power,” she said.

Chen wanted to make a documentary about feminism and came across nushu in her online search. When she realised the script originated from Jiangyong, just a few hours from her hometown, she immediately knew that she had found her graduation project’s topic.

The more she learned about this script, the more she learned about its duality: that it was as much a painful thing as it was a source of strength.

A student uses a smartphone to film Xu writing nushu. Photo: AP

In her documentary, she follows He Yanxin, a formally designated inheritor for nushu who is now in her eighties. She asks Chen: “Do you think nushuhas any use?” Chen says yes. In response, He says: “Nushu is useless.”

He comes from Jiangyong and says she was forced to marry a man she did not want to be with, who physically abused her and tore up photos from nushu meet-ups and workshops she attended. She did not feel that the script had made her life materially better, according to Chen’s first-person account, published on social media.

Yet He is the one who urged her to learn the script.

Formal inheritors of the script have to be from Jiangyong, Chen said, and have to master nushu, but there was nothing stopping her from sharing her love of the script with others.

Beginning in 2022, Chen began spreading the practice. She started an online nushu group, taught writing workshops and set up nushu art exhibitions in cities across China.

Most participants at her writing workshops are women, she said, and some people even bring their mothers. Chen also runs a social media account to promote nushu and its culture beyond Hunan.

A book of nushu calligraphy. Photo: AP

Lu Sirui, a 24-year-old working as a marketer, learned about nushu from online feminist groups and joined Chen’s nushu-focused group on messaging platform WeChat.

“At first, I just knew that it was a women’s inheritance, belonged only among women,” Lu said. “Then, as I got to know it better, I realised that it was a kind of resistance to traditional patriarchal power.”

For Lu, nushu means “a very powerful rebellion” and a bond of sisterhood. She said it was important for women to stick together.

Lu once encountered a property agent in Beijing who, drunk in the middle of the night, knocked on her door and tried to enter her home. Lu said that she picked up a stick at the doorway and ran out to confront him.

Afterwards, she confided in a small feminist community online, where she received comfort and advice on how to handle the situation.

Lu with a book whose title is the word for nushu. Photo: AP

She says communities like that have supported her in the face of gender-based violence, inequality and mother-daughter relationship problems, among other challenges.

Seeing nushu as another representation of sisterhood, Lu bought a textbook and practises the script in her spare time. Even though she is not a formal nushu ambassador, she began hosting nushu workshops at bookstores and bars in Beijing. When organising these events, Lu discovered that very few people had heard of nushu, but the feedback was always positive.

“It’s a manifestation of female strength that transcends time and space,” Lu said.

The timeless saga of “The Legend of the White Snake” weaves a mesmerising tale of forbidden love between a mortal man and an enchanting female snake spirit. Photo: SCMP composite/Wikipedia

How famous Chinese folktale ‘Legend of the White Snake’ portrayed women negatively for centuries in China

Among the thousands of folktales that have graced Chinese history over the millennia, a handful, dubbed “the four great folktales” stand apart as having significant cultural importance.

One of them, The Legend of the White Snake, tells the story of a man, Xu Xian, who falls in love with a female snake spirit, Bai Suzhen.

According to a paper published in June by Dean and Francis Press, the tale has been used throughout the centuries to reinforce negative stereotypes about women.

“In China’s feudal society, capable women — the White Snake — were seen as negative images. Although their human nature continued to strengthen, they still could not escape the oppression of patriarchal society, which fully symbolised the low status and lack of discourse power of Chinese women in traditional society,” wrote Tang Meng, the author.

The earliest versions of the folktale often depict women as treacherous, even homicidal. While newer tellings of The Legend of the White Snakehave softened the characters, the plot always ends with the female snake imprisoned inside a pagoda for decades or centuries.

The folktale first emerged during the Tang dynasty (618-907), and various forms of the legend were told for centuries until Emperor Qianlong (r.1735-1796) finalised an official version during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911).

In an early version from the 9th century, a man (by a different name) has sex with a woman before becoming ill and transforming into water. His family later tracks the woman down and discovers she is a white snake.

A painting from the Summer Palace in Beijing depicts “The Legend of the White Snake” which showcases a serene and mystical scene. Photo: Wikipedia/Shizhao

This tale came during a major development in feudal China during the middle centuries, when women emerged “on the surface of history.” In other words, according to Tang, they became noticed for the first time in official history.

Discover news and insights on women trailblazers, social issues and gender diversity in Asia

Later, during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), another version of the folktale featured a man who met three generations of women and fell in love with the mother, who happens to have killed all of her previous suitors. A Taoist exorcist then performs on the women, and the mother turns into a white snake(her daughter transforms into a chicken and the grandmother an otter). The three women are imprisoned in stone pagodas.

The popularity of the Legend of the White Snake grew during the Qing dynasty when the story became widely performed at Chinese operas, elevating it to the status of a “powerful cultural presence”.

As the story begins to solidify, Xu Xian, the husband, evolves as a character and, by the end of the story, no longer cares that his wife is a snake. However, the White Snake is still considered a threat by an abbot named Fahai, who imprisoned the woman in a pagoda for centuries.

“The Legend of the White Snake” is a popular Chinese folktale that has been adapted into various forms of literature, including books, plays, and poems.

The Tang-era and Ming dynasty versions of The Legend of the White Snakepresent female sexuality as a threat to men. Although other versions of the tale present the White Snake as more sympathetic, they inevitably result in the same conclusion: the woman poses a threat to men, which ends in her imprisonment.

“Even if she is kind-hearted, she should still be seen as a curse, let alone a companion to humanity. This concept is a requirement of Confucian tradition for women to have a gentle personality and a good family background, with the meaning of oppressing women,” wrote Meng Teng, the author of the Dean and Francis Press paper.

The Chinese operas also solidified the presence of a secondary character: the Green Snake. She is the best friend of the White Snake, and they transform into humans together.

She typically plays a supporting role in the tale, but a more modern interpretation of the story brings the Green Snake to the fore.

Numerous films have depicted “The Legend of the White Snake” like the one above in 2019. Photo: iQiyi

The 1993 Hong Kong film The Green Snake, based on the Lilian Lee novel of the same name, centres the mischievous best friend who interferes with the relationship between Xu Xian and the White Snake.

In the film, the Green Snake was played by Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, a retired Hong Kong actress. Taiwan actress Joey Wong Cho-yee played the White Snake.

The movie grossed US$77.4 million at the box office.

Yuhan Chen, while at Fudan University in China, wrote in a paper published in 2022 for Atlantis Press that the film stands apart from tradition for its homoerotic portrayal of the two female leads.

“By accentuating the emotional entanglement among the White Snake, Xu Xian, the Green Snake, and abbot Fahai, the film discusses questions like, what is human nature? What are love and lust? And do humans really have love?” she wrote.

However, she added that, as the White Snake has been softened throughout the centuries due to the popularity of the folktale, the Green Snake “carries on the nature of the aggressive snake, which is unrestrained and has dichotomous attitudes towards love and hatred.”

Besides The Legend of the White Snake the other three great Chinese folktales are Lady Meng Jiang, Butterfly Lovers, and The Cowherd and the Weaving Maid.

|