| | | I append three zerohedge articles from behind the paywall

zerohedge.com

The $20 Trillion Carry Trade Has Finally Blown Up

Late last year, when the latest cycle of the yen carry trade was still in its relative infancy (the USDJPY was in the low 140s then, on its way to a mindblowing and inflation-unleashing 162, not to mention two BOJ intervention), we explained why Japan's economy is now effectively dead, and the only thing missing was declaring the time of death. The reason: the $20 trillion carry trade that the government of Japan has been engaging in for the past 40 years has been one giant a ticking timebomb, one which can not be defused, and when it blows up, it's game over for the Bank of Japan.

Why? well, with the help of DB's chief FX strategist George Saravelos we explained why last December when we also quantified the total size of the trade whose blow up will demand a coordinated central bank rescue in the coming days (not surprisingly the world's central bankers have no idea what has happened and will be panicking after the fact as usual, and unleashing a historic flood of rate cuts in the coming weeks to stabilize the situation).

For those who missed it back in December, here it is again, only this time the carry trade has burst, and either the BOJ will do nothing and watch as its economy implodes, or it will panic reverse the idiotic rate hike it did last week and triples down on easing to contain the crash that just pushed the Nikkei into a bear market; in either case, however, it is unfortunately game over for Japan.

* * *

The government of Japan is engaged in one massive $20 trillion carry trade: here is the toxic dilemma faced by the Japanese central bank now that it has reached the end of the road: on one hand, if the Bank of Japan decides to tighten policy meaningfully, this trade will need to unwind. On the other, if the Bank of Japan drags its feet to keep the carry trade going, it will require higher and higher levels of financial repression but ultimately pose serious financial stability risks, including potentially a collapse in the yen.

As Saravelos puts it, "Either option will have huge welfare and distributional consequences for the Japanese population: if the carry trade unwinds, wealthier and older households will pay the price of higher inflation via rising real rates; if the BoJ delays, younger and poorer households will pay the price via a decline in future real incomes."

Which way this political economy question gets resolved will be key to understanding the policy outlook in Japan in coming years. Not only will it determine the direction of JPY but also Japan’s new inflation equilibrium. Ultimately, however, someone will have to pay the cost of inflation "success."

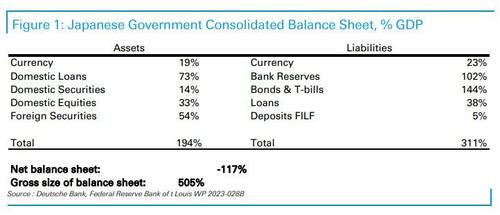

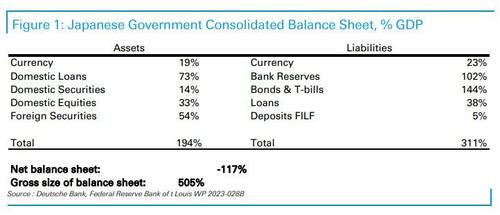

The world's biggest carry tradeThe starting point for the analysis are two excellent papers from the St Louis Fed and IMF, which consolidate the Japanese government’s balance sheet to include the central bank (BoJ), state-owned banks (namely, PostBank) and pension funds (namely, GPIF, the world's biggest pension fund). A consolidation of debt is crucial to understanding why Japan has not faced a debt crisis in recent decades given a public debt/GDP ratio of above 200% that continues to rise. It is also crucial to understanding what the impact of Bank of Japan tightening on the economy will be.

So what does the government’s consolidated balance sheet look like? Below we show the results from the St Louis Fed paper. On the liability side, the Japanese government is primarily funded in low yielding Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) and even lower-cost bank reserves. Over the last ten years the BoJ has effectively swapped out half of the entire JGB stock with even cheaper cash which it created, now held by banks. On the asset side, the Japanese government mostly owns loans, for example via the Fiscal and Investment Loan Fund (FILF), and foreign assets, primarily via Japan’s largest pension fund (the GPIF). The Japanese government's net debt position of 120% of GDP when accounting for all of this is one reason why debt dynamics have not been as poor as what would seem at first sight.

[url=] [/url] [/url]

But what is even more important is the asset-liability mix of this debt. As Saravelos explains, at a gross balance sheet value of around 500% GDP or $20 trillion, the Japanese government's balance sheet is, simply put, one giant carry trade. It goes at the crux of why it has been able to sustain ever-growing levels of nominal debt.

As the authors of the SF paper argue, the government is funding itself at very low real rates imposed by the BoJ on domestic depositors, while earning higher returns on foreign and domestic assets of much higher duration. As that return gap has been expanding, this has created extra fiscal space for the Japanese government. Crucially, one third of this funding is now effectively in overnight cash: if the central bank raises rates the government will have to start paying money to all the banks and the carry trade’s profitability will quickly start unwinding.

Why hasn’t the carry trade blown up?

The first question that then arises is why hasn’t this carry trade blown up over the last few years given the huge sell-off in global fixed income? Everyone else has stopped out of carry trades, why hasn’t Japan? The answer is simple: on the liability side the BoJ controls the government's cost of funding and this has been kept at zero (or indeed negative) despite rising inflation. On the asset side, the Japanese government has benefited from a massive depreciation in the yen which has raised the value of its foreign assets. Nowhere is this more evident than the GPIF, which has delivered cumulative returns in the last few years larger than the past two decades combined. The Japanese government has earned returns from both the FX and fixed income legs of the carry trade. It is not only the Japanese government that has benefited, however. Falling real rates benefit every asset owner in Japan, predominantly older wealthy households. It is often claimed that an ageing population does well from low inflation. In fact, in Japan it is quite the opposite: older households have proven bigger beneficiaries of rising inflation via the de facto decrease in real rates and increase in value of the assets they own.

The moment of reckoningWhat will force this carry trade to unwind ? The simple answer is sustained inflation. Consider what would happen if inflation required the Bank of Japan to hike rates: the liability side of the government balance sheet will take a huge hit via higher interest payments on bank reserves and a decline in the value of JGBs. The asset side will suffer via a rise in real rates and an appreciation of the yen that causes losses on net foreign assets and potentially domestic assets too. The wealthy, older households will take a similar hit too: their asset values will drop while the fiscal capacity of the government to fund pension entitlements will erode. On the flipside, the younger households will be better off. Not only would they earn more on their deposits, the real rate of return on their future stream of savings would rise too.

Are there ways for the government to prevent the pain and required fiscal consolidation that higher inflation would create, especially on older households? There are really just three options, and neither is satisfactory.

- Tax younger households. Rather than reducing pension outlays to help improve the fiscal balance, another alternative is to increase taxation too. The key constraint here would be a political one because older households are wealthier and have already been the primary beneficiaries of the Bank of Japan's QQE policy.

- Prevent real rates from rising. In practice, this would mean that the Bank of Japan tolerates persistently higher inflation by staying behind the curve and eroding the real value of government debt. This is ultimately a variation of fiscal dominance which at its extreme would pose serious financial stability risks. If domestic households reach the conclusion that the yen’s monetary anchor is lost, we would ultimately see capital flight and a dramatic depreciation in the yen (this is the most likely outcome).

- Don’t pay the banks. The single biggest funder of the Japanese government’s carry trade is the banking system via its large holdings of excess reserves. There is then one straightforward way of preventing the central bank (and by extension) the government’s interest bill from rising: apply reverse tiering to excess reserve balances by not paying interest. This is an approach that is already followed by Switzerland and may well work in the short-term. Ultimately, however, it creates serious financial stability risks because it prevents banks from passing on the full benefit of interest rate increases to depositors. The end result would be to create conditions for deposit flight similar to what we saw in the US regional banks crisis this year.

Of course, none of the options discussed above are sustainable over the long-term. However, they help highlight a menu of policy choices that can be deployed to delay or attenuate the distributional trade-offs that a higher inflation regime in Japan creates (all of them would lead to tremendous social upheaval, and political instability as the period of can kicking is now over).

ConclusionThe last few years of extremely easy monetary policy have been relatively straightforward from a Japanese political economy perspective: falling real rates, improving fiscal space and income redistribution that has favored wealthy, older voters. If Japan is indeed embarking on a new chapter of structurally higher inflation, however, the choices going forward are going to be far less easy. Adjusting to a higher inflation equilibrium will require rising real rates and greater fiscal consolidation, in turn more damaging to older and wealthier voters, unless the younger voters get taxed. While this adjustment can be delayed, it would be at the cost of even greater financial instability down the road, and a much weaker yen. The yen, in turn, can only embark on a sustained uptrend when the Japanese government – via BoJ rate hikes – is forced to unwind the world's last big surviving carry trade in the post-COVID world, one which has allowed Japan to enjoy a period of eerie social and political calm. Those days, however, are about to come to a thunderous end. |

|

[/url]

[/url]