Hurricane Threat Poised to Keep Rising, Experts WarnMany coastal cities are still unprepared for the extremes ahead because they are designed for a climate that no longer exists.

Bob Berwyn October 11, 2024

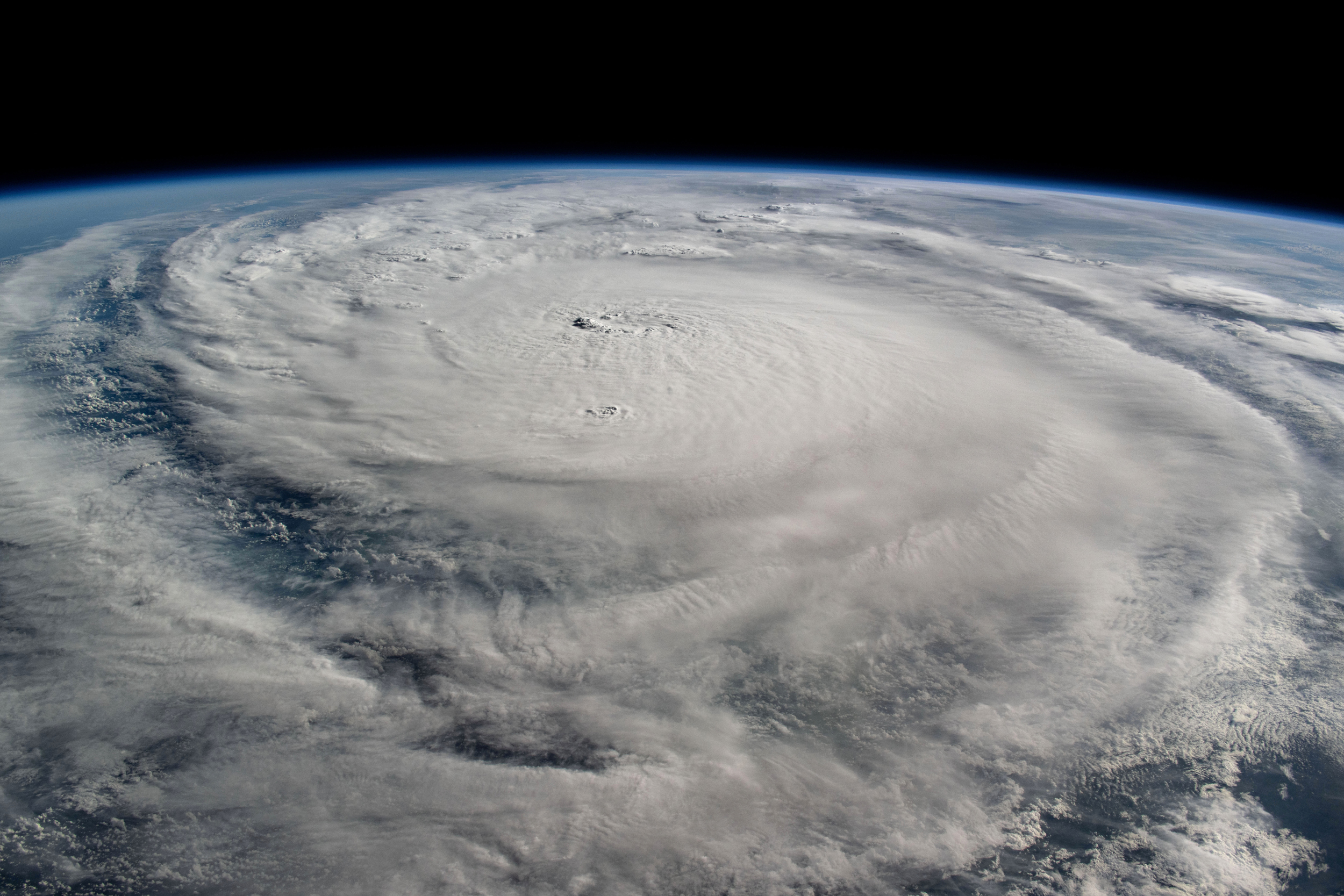

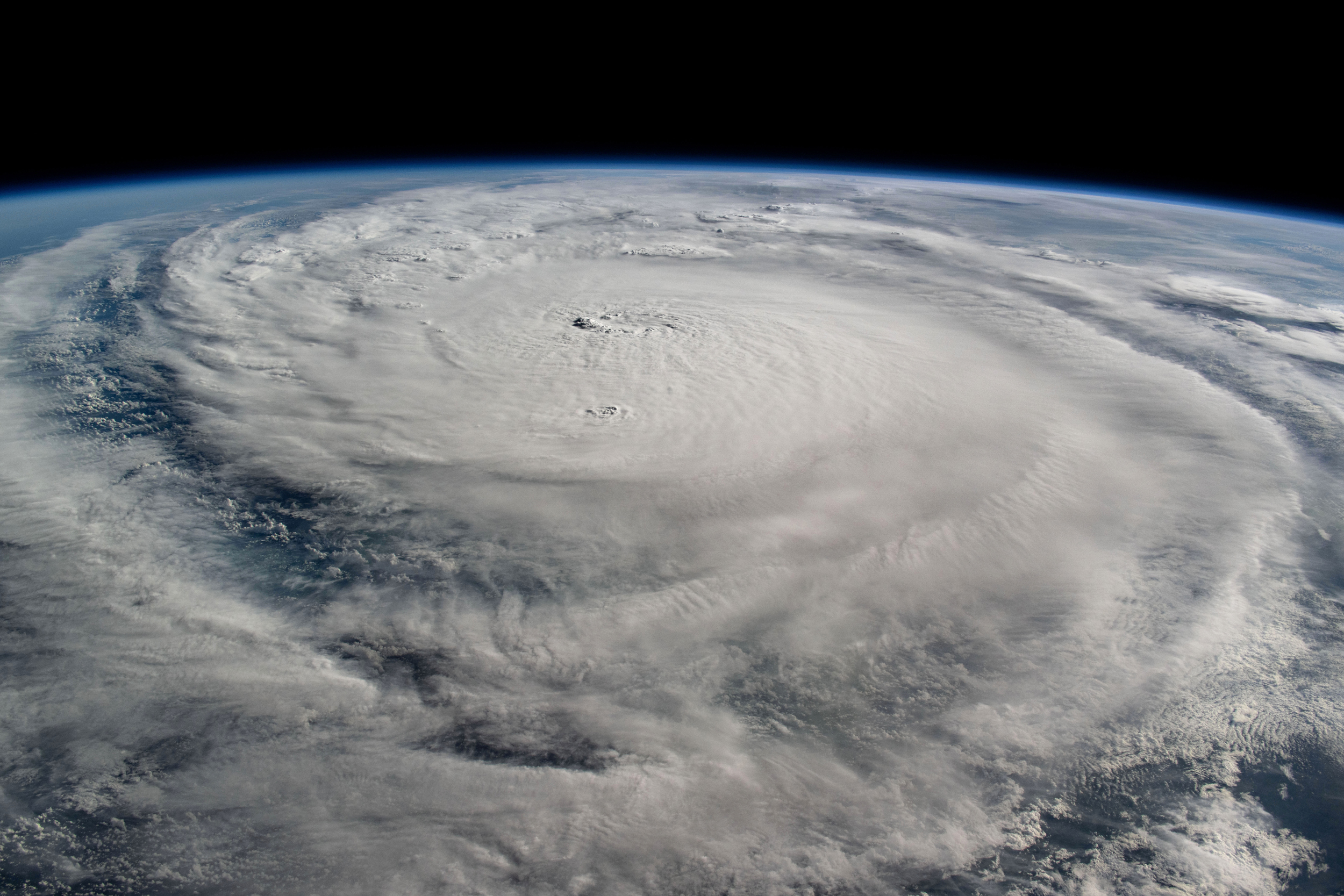

Hurricane Milton, a Category 5 storm at the time of this photo, is seen from the International Space Station in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Credit: NASA Hurricane Milton, a Category 5 storm at the time of this photo, is seen from the International Space Station in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Credit: NASA

As people in parts of the southeastern United States try to pick up the pieces of their broken homes, lives and dreams after the twin gut punches delivered by Hurricane Helene and Hurricane Milton, climate scientists have some unwelcome news. Global warming, along with reductions of sulfate aerosol pollution, is likely to fuel even more powerful and destructive storms in the years and decades ahead.

Every 1 degree Celsius of warming increases maximum winds in the strongest storm by about 12 percent, which equates to a 40 percent increase in wind damage, said climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania.

“We can expect proportionally larger storm surges, rainfall and flooding,” he said. “One recent study suggests that human-caused warming boosted the Helene-related flooding in the southeastern U.S. by 40 percent. All of this continues to increase as long as the warming continues until our carbon emissions reach zero.”

Current hurricanes and other tropical systems are not near their theoretical size limit, either, although hurricanes in the Atlantic are constrained by geography, said atmospheric scientist Kevin Trenberth, distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research and an honorary academic with the Department of Physics at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

“The radius of a hurricane may be 500 kilometers, but moisture flows into the storm from 2,000 kilometers away,” he said. “So if there is land within that distance, there is a lot less moisture and dry tongues come in and weaken the storm. The northwestern Pacific is much less limited in that regard and that is where the biggest and strongest typhoons have been found.”

Trenberth has been warning for years that many urban areas around the world are far from being prepared for the sharp spike in flood risks caused by global warming because “flood risk management and the design of flood protection systems are almost exclusively based on the observed historical record of extreme precipitation and floods, even though most credible scenarios of climate change point to increased risk of extremes.”

“Guidance is urgently needed in this area; floods are one of the world’s most damaging and dangerous natural hazards, with major populations and assets at risk,” he wrote in an upcoming paper for the World Climate Research Programme.

“Hurricane impacts are highly dependent on prior planning, which is generally inadequate in Florida and Texas,” he said. “Red states. Not

enough government and not enough attention to flood plains and drainage systems.”

Not Just Warmer OceansThe increase in Atlantic hurricane activity since the early 1990s is “indisputable” and commonly attributed to global warming and overheated oceans by the media, but a reduction of air pollution may be an even more important factor, said MIT hurricane and climate researcher Kerry Emanuel.

In a 2022 paper in Nature Communications, Emanuel and co-author Raphaël Rousseau-Rizzi found evidence that high air pollution levels in the form of sulfate aerosols during the 1970s and 1980s suppressed hurricane activity by reducing rainfall in Africa’s Sahara-Sahel region. That increased the amount of dust dispersing across the Atlantic hurricane region, which cooled the ocean. But the lull ended when pollution levels dropped in response to regulations, leading to the subsequent increase in hurricane activity.

This story is funded by readers like you.Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now

On the timescale of how human activities affect hurricanes, ocean temperature changes are best seen as an effect, and not a cause. Decreasing aerosols and increasing greenhouse gases both lead to warmer oceans.

“But the two causes, even if they contributed equally to sea surface temperature, would not have contributed equally to favorable hurricane conditions, with the aerosols being the more influential cause,” he said.

The complex climate effects of reducing sulfate aerosol pollution will persist in the decades ahead as countries strive for cleaner air, and those effects can vary regionally. For example, a study published last May in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science showed that reductions of aerosol pollution from Chinese industrial sources exacerbated ocean heat waves in the northern Pacific Ocean, boosting the maximum ocean temperatures by 30 percent in that region between 2010 and 2020. Those ocean heat waves killed thousands of whales and fish, and spurred outbreaks of toxin-producing algae that shut down shell fishing along parts of the west coast of North America.

Expect Increasing Climate ImpactsNot every storm in the future will be bigger than Milton, but the impacts will keep getting worse, said Andra Garner, an associate professor at Rowan University in New Jersey who studies sea-level rise and tropical cyclones.

“We know that, in a warmer world, regardless of storm characteristics, flooding from hurricanes will get worse because our sea levels are getting higher,” she said.

Garner co-authored a 2017 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that combined modeled hurricane storm surges with paleo sea-level records and future sea-level projections to see how overall flood heights have evolved.

They found that a 7.4-foot hurricane-related storm surge flood—a little less than that caused by Hurricane Sandy in 2012—has gone from being a 500-year event in pre-industrial times to being a 25-year flood in the modern era (1970-2005). And it could happen as often as every five years or so by the middle of this century.

“We know that, in a warmer world, regardless of storm characteristics, flooding from hurricanes will get worse because our sea levels are getting higher.”

— Andra Garner, Rowan University associate professornone“In other words, this kind of significant flood has gone from something a person may never have seen in their lifetime to something that a person could see happen several times in their lifetime,” she said. “And it’s potentially headed towards the kind of event that could become relatively frequent.”

Garner added, “We know that sea levels in Florida, like those in New York City, have been rising even faster than the global average as our planet has warmed. So, it’s not unreasonable to expect that we could see similarly large increases in storm surge flood heights over time along the Florida coastline.”

She pointed to Milton as an example of the trend her study found: “While the storm is notable for its intensity, and how quickly it reached that intensity, flooding from the storm will be even worse than it would have been if the same storm had occurred decades ago, and that increase in flooding is due primarily to rising sea levels.”

As Hurricane Milton formed, meteorologists noted its somewhat unusual west-to-east path, perhaps another sign that global warming is influencing hurricanes in ways that will affect millions of coastal residents in the path of those storms.

In a warmer climate, research shows there is a tendency for more storms to form off the southeast coast of the U.S., Garner said, as well as a tendency for those storms to move more slowly along the U.S. Atlantic Coast, with more damage to coastal communities.

“Long-term studies are showing the potential for a warming climate to impact hurricane tracks in a way that can have major consequences for our coastlines,” she said. We need to be taking that kind of information into account when we think about how to protect our coastlines in a warming climate.” |

Hurricane Milton, a Category 5 storm at the time of this photo, is seen from the International Space Station in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Credit: NASA

Hurricane Milton, a Category 5 storm at the time of this photo, is seen from the International Space Station in the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of the Yucatan Peninsula. Credit: NASA