Nation & World

Nation & World Politics

NIH cuts billions of dollars in biomedical funding, effective immediately

Feb. 8, 2025 at 10:11 am

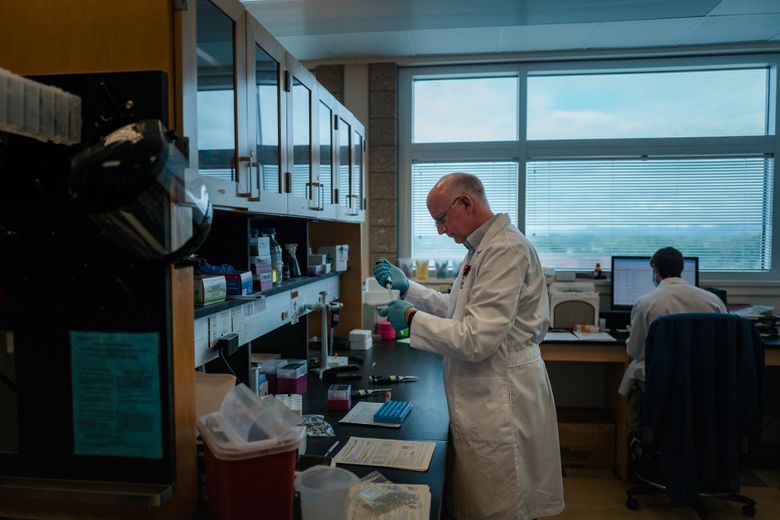

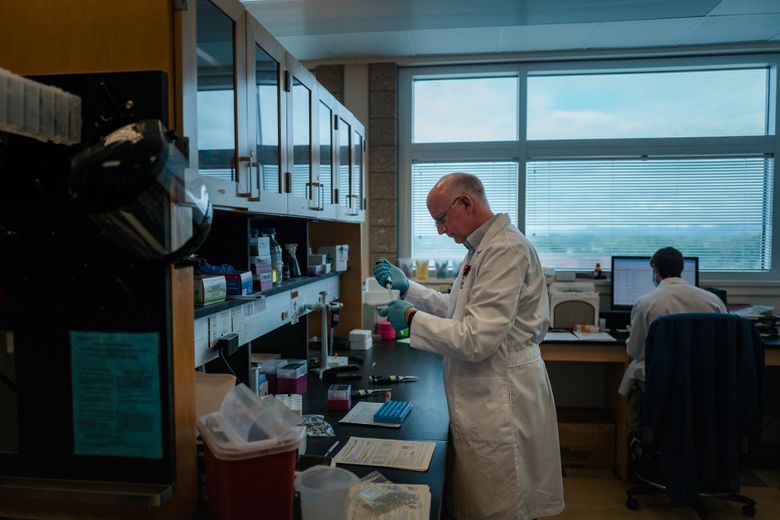

A cancer research lab at the Gunderson Institute in LaCrosse, Wisconsin. Virtually all universities and medical research centers across the country would be affected by the grant cuts. (Ryan Christopher Jones for The Washington Post).

By

Lena H. Sun

Carolyn Y. Johnson

and

Dan Diamond

The Washington Post

The Trump administration is cutting billions of dollars in biomedical research funding, alarming academic leaders who said it would imperil their universities and medical centers and drawing swift rebukes from Democrats who predicted dire consequences for scientific research.

The move, announced Friday night by the National Institutes of Health, drastically cuts NIH’s funding for “indirect” costs related to research. These are the administrative requirements, facilities and other operations that many scientists say are essential but that some Republicans have claimed are superfluous.

“The United States should have the best medical research in the world,” NIH said in its announcement. “It is accordingly vital to ensure that as many funds as possible go towards direct scientific research costs rather than administrative overhead.”

In a post on social media, NIH said the change would save more than $4 billion a year, effective immediately. The note singled out Harvard University, Yale University and Johns Hopkins University’s multibillion-dollar endowments, implying that many universities do not need the added federal funding.

The policy, essentially a massive budget cut to science and medical centers across the country, was quickly denounced as devastating by universities and research organizations.

Related Trump’s DEI order leaves academic researchers fearful of political influence over grants

Some scientists said the move could threaten research already underway and noted that their universities have a fraction of the endowments of schools such as Harvard and Yale. Industry leaders also questioned whether the move was legal.

“This is a surefire way to cripple lifesaving research and innovation,” Matt Owens, president of COGR – the Council on Government Relations, an association of research institutions, academic medical centers and research institutes – wrote in an email.

The funding is “part and parcel of the total costs of conducting world class research,” Owens added. “We are carefully reviewing this policy change as it contradicts current law and policy. America’s competitors will relish this self-inflicted wound.”

Trump allies hailed NIH’s move. The U.S. DOGE Service, the agency led by billionaire Elon Musk that has focused on slashing government spending, said NIH’s new policy would save billions of dollars in “excessive grant administrative costs.”

“Amazing job by NIH team,” DOGE posted on social media.

Republicans in recent years had weighed cutting federal funds for overhead costs at universities, with the first Trump administration abandoning a plan to do so amid pressure from biomedical leaders.

Democrats immediately castigated the Trump administration, saying NIH’s move would imperil clinical research, patient care and laboratory operations, among other health-care priorities.

“Just because Elon Musk doesn’t understand indirect costs doesn’t mean Americans should have to pay the price with their lives,” Sen. Patty Murray (D-Washington) said in a statement.

The NIH’s policy shift centers on how it awards grants to support scientific research on cancer, heart disease and diabetes. It also provides overhead funds to cover the costs of facilities, administration and other approved costs. That amount is a percentage of the direct research costs in the grant, and varies by institutions. But it can be more than half of the direct costs. A research award for $100,000 in direct costs, for example, could come with $50,000 in indirect costs, making the total grant $150,000.

In fiscal year 2023, out of $35 billion in awarded grants, $9 billion went to overhead, NIH said.

In its announcement, NIH said that on average, the overhead rate has been about 27 to 28 percent of the direct research funding in the grant but that “many organizations” charge indirect rates of over 50 percent and in some cases more than 60 percent. The agency’s new policy will cap the rate at 15 percent and take effect on Monday, cutting tens of millions of dollars or more in funding for many universities – virtually overnight.

“These are real costs and will cause MIT to decrease the amount of critical life sciences research that the Institute is able to execute,” said Maria Zuber, a geophysicist and MIT’s presidential adviser for science and technology policy, in an email.

“I expect it will cause some universities to not be able to afford to accept federal life science grants. I am at a loss to understand how this is beneficial to Americans,” Zuber added.

Kimryn Rathmell, who led the National Cancer Institute under the Biden administration before stepping down last month, said she was grappling with the difficult choices ahead for the scientific field.

“This abrupt change in the way grants are funded will have devastating consequences on medical science,” said Rathmell, a longtime cancer researcher at Vanderbilt University, predicting that the policy shift would have both health and economic consequences. “Many people will lose jobs, clinical trials will halt, and this will slow down progress toward cures for cancer and effective prevention of illness.”

Jeffrey Flier, the former dean of Harvard Medical School, said that the move came as a shock to him and his colleagues across academia.

“A sane government would never do this,” Flier wrote on social media.

Several researchers said that NIH’s high rate of funding for indirect costs helped subsidize the infrastructure necessary for their work – everything from a building’s heating and electricity to personnel. They also said that the government’s willingness to fund indirect costs at more than 50 percent balanced out the lower rate that researchers tend to receive from private foundations, which were more likely to fund 15 percent of the indirect costs.

NIH said it was cutting its rate of funding indirect costs to be more in line with private foundations that fund research, noting that many foundations do not fund indirect costs at all.

Republicans had weighed similar measures in the past. President Donald Trump in 2017 proposed capping indirect costs at 10 percent, but the effort did not succeed. The idea was more recently included in Project 2025, the conservative blueprint for a second Trump term, which blamed the added spending for helping subsidize diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives.

“Congress should cap the indirect cost rate paid to universities so that it does not exceed the lowest rate a university accepts from a private organization to fund research efforts,” it says in Project 2025’s blueprint. “This market-based reform would help reduce federal taxpayer subsidization of leftist agendas.”

Some outside analysts also praised NIH, saying that funding for researchers’ administrative costs has been wrongly redirected toward universities that use the funding for unrelated priorities.

“It’s a huge victory for government efficiency. We should be funding scientists, not bureaucrats,” said Avik Roy, founder of the Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity, a think tank that promotes free markets.

But some Trump officials said they were wary of the sudden policy change, noting the immediate blowback across academia, and predicted that the move would be opposed by GOP lawmakers worried about the effect on their constituents.

“Red states have universities too,” one Trump official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the press, wrote in a message.

This story was originally published at washingtonpost.com. Read it here.

seattletimes.com |