re <<Cost So Much>> ...

... why does everything cost so much they do not ... after DeepSeeking, or post-J-10C-ing / solid-PL15-ing

bloomberg.com

DeepSeek’s ‘Tech Madman’ Founder Is Threatening US Dominance in AI Race

The company’s sudden emergence illustrates how China’s industry is thriving despite Washington’s efforts to slow it down.

DeepSeek founder Liang Wenfeng meeting with President Xi Jinping in Beijing in February.

Photographer: Florence Lo/Reuters

By Bloomberg Businessweek

May 14, 2025 at 5:00 AM GMT+8

With his wispy frame and reserved style, Liang Wenfeng can come off as shy, nervous even, in meetings. The founder of DeepSeek—the Chinese startup that recently upended the world of artificial intelligence—is prone to faltering speech and prolonged silences. But new hires learn quickly not to mistake his quiet rumination for timidity. Once Liang processes the finer points of a discussion, he fires off precise, hard-to-answer questions about model architecture, computing costs and the other intricacies of DeepSeek’s AI systems.

Employees refer to Liang as lao ban, or “boss,” a common sign of respect for business superiors in China. What’s uncommon is just how much their lâobân empowers young researchers and even interns to take on big experimental projects, habitually stopping by their desks for updates and pushing them to consider unusual engineering paths. The more technical the conversation the better, especially if it leads to real performance gains, milestones Liang has personally shared on their internal Lark messaging channel. “He’s a true nerd,” says one former DeepSeek staffer who, like many people interviewed for this article, requested anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly about the company. “Sometimes, I felt he understood the research better than his researchers.”

Liang and his young company catapulted to international prominence in January when it released R1, an AI model that had the feel of an explosive breakthrough. R1 beat the dominant Western players on several standardized tests commonly used to assess AI performance, yet DeepSeek claimed to have built its base model for about 5% of the estimated cost of GPT-4, the model undergirding OpenAI’s ChatGPT.

The test results triggered a $1 trillion selloff in US markets and sparked thorny questions about the US strategy to use export controls to slow China’s progress on AI. Amazon and Microsoft raced to add DeepSeek’s models to their cloud offerings, alongside rivals from Meta and Mistral AI. “Basically over a weekend, the interest in DeepSeek just grew so much that we got into action,” says Atul Deo, who oversees Amazon.com Inc.’s language model marketplace.

DeepSeek cleared the fogged window through which Americans have viewed much of China’s AI scene: shrouded in mystery, easier to dismiss as an exaggerated specter but very likely more daunting than they’re willing to admit. Before the startup’s emergence, many US companies and policymakers held the comforting view that China still lagged significantly behind Silicon Valley, giving them time to prepare for eventual parity or to prevent China from ever getting there.

The US Dominates AI Investment ...Private investment in AI

Source: Quid, compiled by Stanford University AI Index

The reality is that Hangzhou, where DeepSeek is based, and other Chinese high-tech centers have been roaring with little AI dragons, as AI startups are often called. Sophisticated chatbots from homegrown startups such as MiniMax and Moonshot AI have rocketed in popularity, including in the US. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd.’s Qwen family of large language models consistently ranks near the top of prominent leaderboards among LLMs from Google and Anthropic; Baidu Inc.’s chief executive officer, Robin Li, boasted in April that the search giant could develop models that were as good as DeepSeek’s but even cheaper, thanks to its new supercomputer, assembled with in-house chips. Huawei Technologies Co. is likewise winning plaudits for the products it’s designed to compete against equipment from Nvidia Corp., whose graphics processing units (GPUs) power the most advanced AI models in the US and Europe.

... But China’s Tech Is Catching Up

Performance measure of top AI models on LMSYS Chatbot Arena

Source: LMSYS, compiled by Stanford University AI Index

Note: Chatbot Arena is an open-source platform for evaluating AI through human preference developed by researchers at LMArena

It wasn’t that long ago that the Chinese Communist Party was clipping the wings of what it saw as an out-of-control tech sector. Antitrust probes and data-compliance reviews were initiated, luminaries such as Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma faded from public view, and new regulations were imposed on social media, gig economy and gaming apps. Now the CCP is lifting up its domestic tech industry in the face of foreign interference. President Xi Jinpingis marshaling resources to AI and semiconductors, emboldening China’s high-skilled workforce and calling for “an independent, controllable and collaborative” software and hardware ecosystem.

Also propelling China’s recent strides, ironically, are geopolitical constraints aimed at slowing its AI momentum. Wei Sun, an analyst at Counterpoint Technology Market Research, says the AI gap between the US and China is now measured in months, not years. “In China there’s a collective ethic and a willingness to work with intensity that results in executional superiority,” says Sun, noting that the forced scarcity of Nvidia chips unearthed novel AI innovations. “This dynamic creates a kind of Darwinian pressure: Survival goes to those who can do more with less.”

Where China sees innovation, many in the US continue to suspect malfeasance. An April report from a bipartisan House of Representatives committee alleged “significant” ties between DeepSeek and the Chinese government, concluding that the company unlawfully stole data from OpenAI and represented a “profound threat” to US national security. Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, has called for more US export controls, contending in a 3,400-word blog post that DeepSeek must have smuggled significant quantities of Nvidia GPUs, including its state-of-the-art H100s. (Bloomberg News recently reported that US officials are probing whether DeepSeek circumvented export restrictions by purchasing prohibited chips through third parties in Singapore.)

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has cited DeepSeek as a reason for tougher restrictions on chip exports to China.Photographer: Chesnot/Getty Images

The Chinese Embassy has rejected the House committee’s claims as “groundless.” Nvidia has said that DeepSeek’s chips were export-compliant and that more restrictions could benefit Chinese semiconductors. A spokesperson for the chipmaker says forcing DeepSeek to use more chips and services from China would “boost Huawei and foreign AI infrastructure providers.”

The company at the center of this debate continues to be something of an enigma. DeepSeek prides itself on open-sourcing its AI technology while not being open whatsoever about its inner workings or intentions. It reveals hyperspecific details of its research in public papers but won’t provide basic information about the general costs of building its AI, the current makeup of its GPUs or the origins of its data.

“We don’t know what DeepSeek’s true motivations are. It’s a bit of a black box” Liang himself has long been known to be so inherently unsociable that some leaders of China’s AI scene privately call him “Tech Madman,” a variation on a nickname reserved for eccentric entrepreneurs with outsize ambitions. He hasn’t granted a single press interview in the past 10 months, and few knew what he looked like until a photograph surfaced of his boyish, bespectacled face during a recent hearing with Chinese Premier Li Qiang. Liang and his colleagues didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment for this article, except for an autoreply from one employee that said the inquiry was being processed: “Thank you for your attention and support for DeepSeek!” her email added.

Liang in January.Source: Zuma Press

To further understand how the company works and how it fits into the country’s broader AI ambitions, Bloomberg Businessweek spoke with 11 former employees of Liang’s, along with more than three dozen analysts, venture capitalists and executives close to China’s AI industry.

The lack of a public presence has allowed critics such as Amodei and OpenAI head Sam Altman to fill the void with aspersions, which resonate with US audiences who are primed to see Chinese technology as a shadowy threat. But even those who remain wary of DeepSeek are being forced to grapple with the undeniable prowess of its AI. Dmitry Shevelenko, the chief business officer of Perplexity AI Inc., says not a single person at his company, which makes an AI-powered search product, has managed to communicate with any counterparts at DeepSeek. Nevertheless, Perplexity has embraced DeepSeek’s tech, hosting it only on servers in the US and Europe and post-training it to remove any datasets indicative of CCP censorship. Perplexity branded it R1 1776 (a reference to the year of the US’s founding), which Shevelenko describes as an homage to freedom. “We don’t know what DeepSeek’s true motivations are,” he says. “It’s a bit of a black box.”

DeepSeek had anticipated its AI might cause concerns abroad. In an overlooked virtual presentation at an Nvidia developer conference in March 2024, Deli Chen, a deep-learning researcher at DeepSeek, spoke of how values ought to be “decoupled” from LLMs and adapted to different societies. On one coldly logical slide, Chen showed a DeepSeek prototype for customizing the ethical standards built into chatbots being used by people of various backgrounds. With a quick tap of a button, developers could set the legality of issues including gambling, euthanasia, sex work, gun ownership, cannabis and surrogacy. “All they need to do is to select options that fit their needs, and then they will be able to enjoy a model service that is tailored specifically to their values,” Chen explained.

Finding such efficient workarounds was always the cultural norm at DeepSeek. Liang and his friends studied various technical fields at Zhejiang University in the mid-2000s—machine learning, signal processing, electronic engineering, etc.—and, apparently for kicks (and, you know, for cash), developed computer programs to trade stocks during the global financial crisis.

After graduating, Liang continued building quant-trading systems on his own, earning a small fortune before joining forces with several of his university friends in Hangzhou, where they launched what became known as High-Flyer Quant in 2015.

Early job postings boasted of luring top talent from Google and Facebook and sought math and coding “geeks” with the “quirky brilliance” of Sheldon, the awkward main character of the sitcom The Big Bang Theory. They promised free snacks, Herman Miller chairs, poker nights, an office culture that smiled upon T-shirts and slippers and, with a dollop of fintech bro culture, the opportunity to work with “adorable, soft-spoken girls born in the 1990s” and “a sharp goddess who returned from Wall Street.”

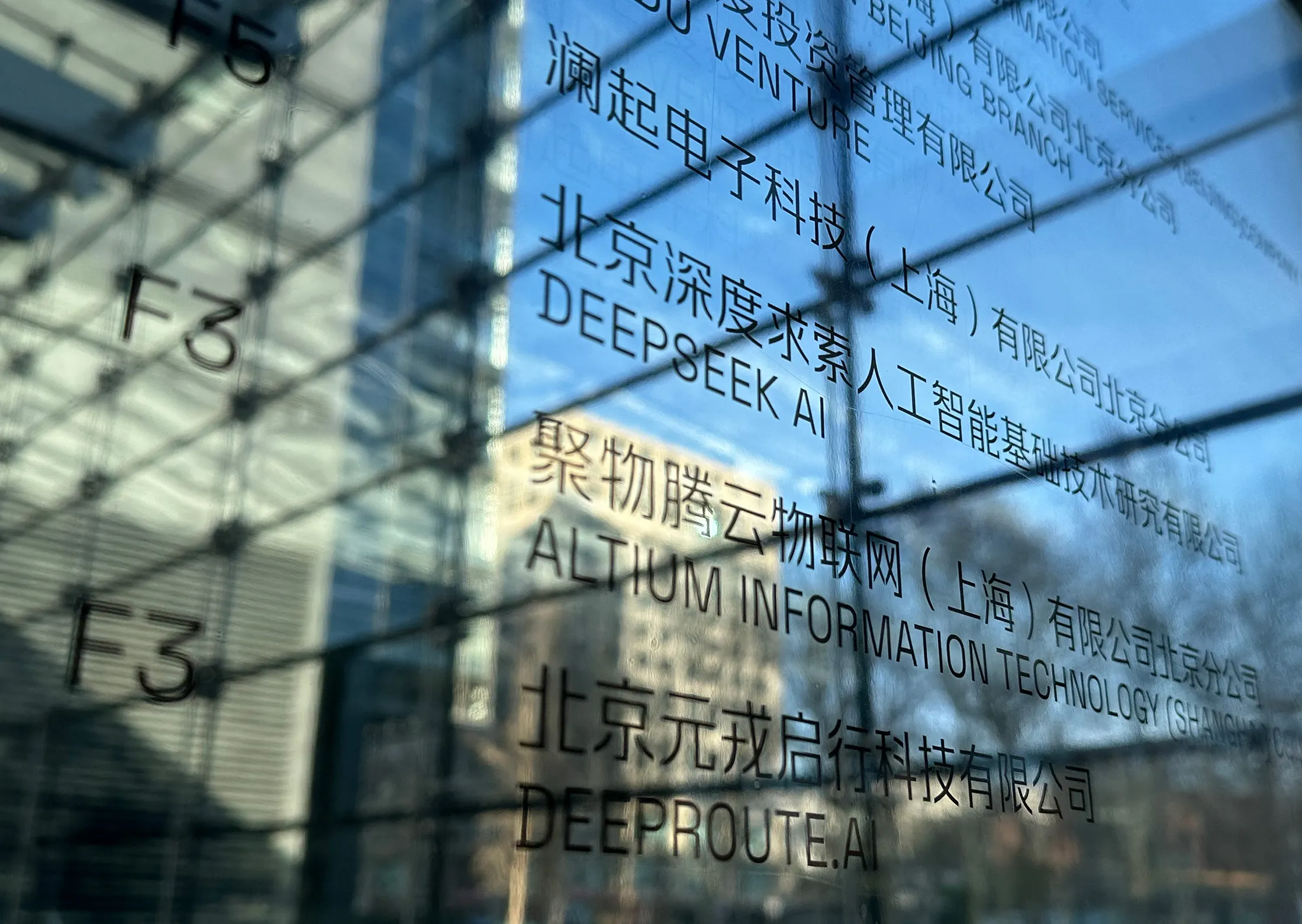

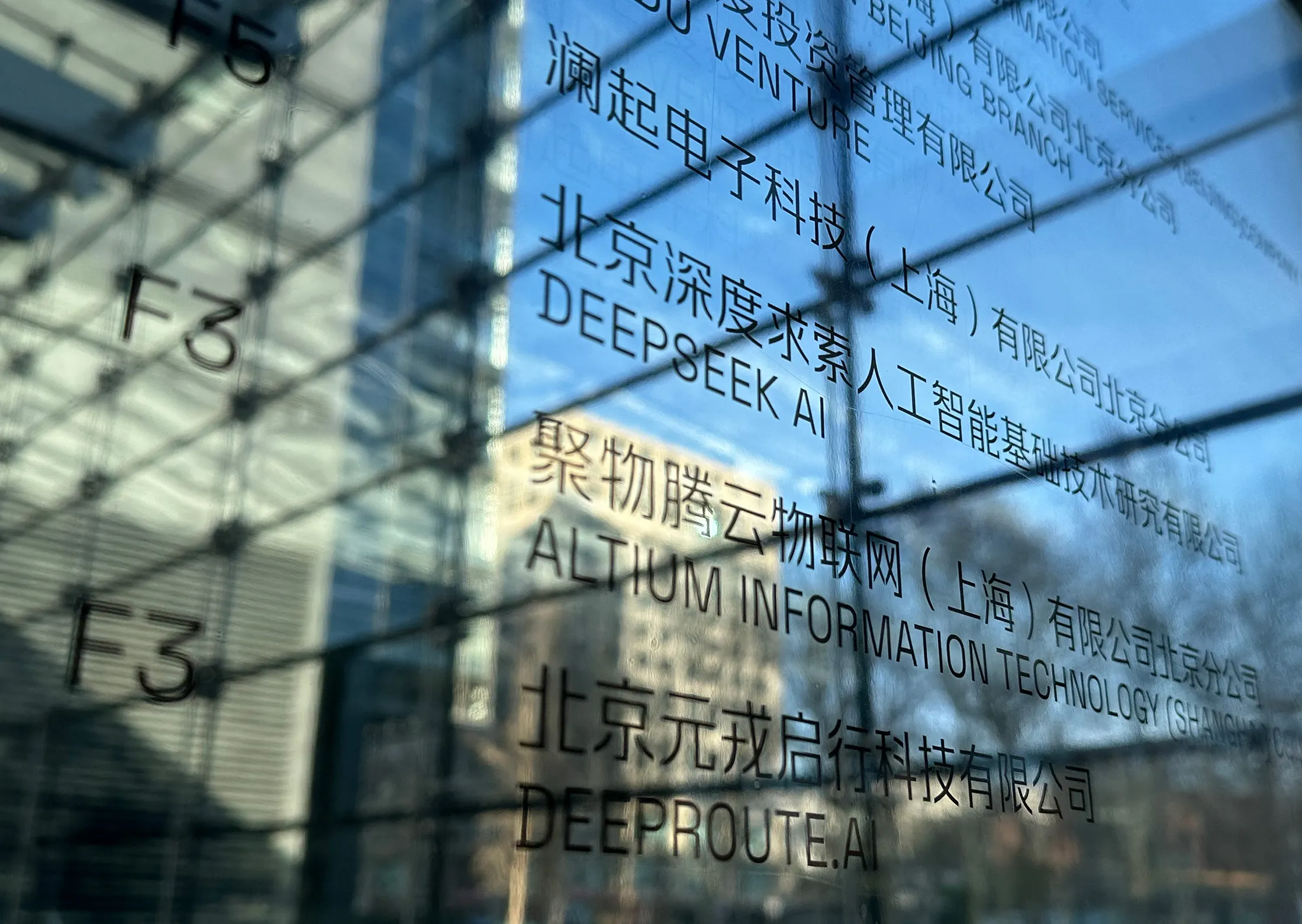

DeepSeek’s Beijing office.Photographer: Peter Catterall/AFP/Getty Images

As would be the case with DeepSeek, High-Flyer cultivated a sense of mystery—its first social media post referred to Liang only as “Mr. L”—while committing itself to a kind of lemme-prove-it transparency. Every Friday, High-Flyer would post charts of the performance of its 10 original funds on the Chinese super-app WeChat. Before making the weekly data available only to registered investors in the summer of 2016, the portfolio was seeing average annualized returns of 35%.

Billions of dollars eventually flowed into High-Flyer’s holdings, and its investment and research group increased to more than 100 employees. Liang started recruiting in earnest for an AI division in 2019, aiming to mine gargantuan datasets to spot undervalued stocks, tiny price fluctuations for high-frequency trading and macro trends that industry-specific investors were missing. By the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, he and his team had constructed a high-performance computing system of interconnected processors running in tandem, a setup known as a cluster. For this cluster, High-Flyer said it had acquired 1,000 Nvidia 2080Ti chips—commonly used by gamers and 3D artists—and an additional 100 Volta-series GPUs. (The Volta GPU, aka the V100, was Nvidia’s first AI-optimized processor.) Whereas High-Flyer’s previous, smaller computing architecture required two months to train a new economic analysis model, its new equipment needed less than four days to process the same workload.

These finance models were impressive but much smaller than the generalist models US operations like OpenAI were building. Liang pushed for the construction of a substantially bigger supercomputer consisting of Nvidia’s then-new A100 GPUs, its upgraded successor to the V100. A former High-Flyer engineer involved with the project says Liang was “the single biggest user” of the growing cluster, estimating 80% of the computer processing used to develop models was assigned to his username. This ex-engineer says Liang seemed obsessed with deep learning, calling it “his expensive hobby.” Plowing hundreds of millions of dollars into such AI infrastructure was probably overkill for a quant firm, but Liang had generated more than enough profits to afford it. “Small money for Liang at the time,” the engineer recalls. “More computing power, better models, more gains in trading.”

At least that was the hope. High-Flyer, which was then managing roughly $14.1 billion in assets, apologized in a December 2021 letterto stakeholders for a streak of disappointing returns. The firm blamed the downturn on its AI systems, which it said had made smart stock picks but failed to proficiently time exits from those trades amid the volatility of the pandemic. Even so, it decided to literally double down on AI: In January 2022, High-Flyer posted on social media that it had amassed 5,000 Nvidia A100s, each of which usually costs tens of thousands of dollars. In March it announced this cluster had expanded to 10,000, a mere six months before Nvidia warned new US restrictions could affect exports of such chips to China.

It’s unclear how much of this infrastructure was ultimately intended for quant trading versus Liang’s expensive hobby. The next spring, about five months after OpenAI introduced ChatGPT, he spun out DeepSeek as an independent research lab. At separate offices in Hangzhou and Beijing, finance was no longer the focus. In an unsigned manifesto rife with platitudes, High-Flyer vowed to shun mediocrity and tackle the hardest challenges of the AI revolution. Its ultimate goal: artificial general intelligence.

Featured in the June 2025 issue of Bloomberg Businessweek. Subscribe now.Illustration: 731

Throughout 2023 the DeepSeek lab raced to build an AI code assistant, a general-knowledge chatbot and a text-to-3D-art generator. Liang brought over engineers from High-Flyer and recruited more from Microsoft Corp.’s Beijing office and leading Chinese tech companies and universities. Bo “Benjamin” Liu, who joined as a student researcher that September prior to starting a Ph.D., says Liang frequently gave interns crucial jobs that elsewhere would be assigned to senior employees. “Take me as an example: When I got to the company, no one was working on the RLHF infra”—the infrastructure needed to support an important technique known as reinforcement learning from human feedback—“so he just let me do it,” Liu says. “He will trust you to do the things no one has done before.” (That trust came with a secondary benefit to DeepSeek: It paid interns the equivalent of $140 per day with a $420 monthly housing subsidy, generous compensation in China but about a third of what interns make at AI companies in the US, and a tiny fraction of what full-time Silicon Valley engineers earn.)

Liang placed a huge and early bet on sparsity, a technique for training and running LLMs more efficiently by breaking them down into specialties, according to two ex-DeepSeek researchers. When you asked the original ChatGPT a question, its entire LLM brain would activate to determine the ideal answer, whether you asked for the sum of 2 + 2 or a pie recipe. A sparse model, by contrast, would make better use of resources by being partitioned into “experts,” with only the relevant ones being activated in response to any particular prompt.

A sparse approach can lead to enormous savings on computing costs, but it gets extremely complex. If a question isn’t processed by enough circuits of the brain or is sent to the wrong lobes, answer quality will degrade. (The math brain would know how to use pi in a formula, but not what goes into that pie recipe, for instance.) Liang saw progress in this area from Google and French unicorn Mistral, which had released a sparse model in December 2023 that was divided into eight experts, with each query activating two of the most relevant ones based on context. He rallied his team to design models with ever-more experts, a technique that comes with the potential of increasing hallucinations and fragmenting the AI’s knowledge. “This sparked significant internal debate,” says the former DeepSeek staffer.

More breakthroughs followed, each shared publicly and increasingly catching the attention of Chinese competitors. Then, in late 2024, DeepSeek released V3, a general-purpose AI model that was about 65% larger than Meta Platforms Inc.’s equivalent, which was then the biggest open-source LLM available. But it was a lengthy V3 research paper that really grabbed the attention of executives at Google, OpenAI and Microsoft, about a month before DeepSeek broke into the wider consciousness with its R1 reasoning model. One shocking statistic that leapt off the PDF: DeepSeek implied that V3’s overall development had cost a mere $5.6 million. It’s likely this sum referred only to the final training run—a data-refinement process that transforms a model’s previous prototypes into a complete product—but many people perceived it as an insanely low budget for the entire project. By comparison, cumulative training for the most advanced frontier models can run $100 million or more. Anthropic’s Amodei even predicted (before the rise of DeepSeek) that next-generation models will each cost anywhere from $10 billion to $100 billion to train.

Leandro von Werra, head of research for popular AI platform Hugging Face Inc., which hosts rankings of LLMs, says DeepSeek’s “architectural innovation” wasn’t the most striking thing about its model. The biggest revelation he took from its research paper was that the company must have developed high-quality data—either cleverly cleaned up from the web or extracted through other means—to bring V3 to life. “Without very strong datasets, the models will lack performance,” says von Werra. “From the report it becomes very clear that DeepSeek has one of the best training datasets for LLMs out there. Unfortunately the report covers the dataset in half a page out of 50 pages.”

DeepSeek exhibited its rapid progress because Liang saw the open-source ethos as integral to his philosophy. He believed that hiding proprietary techniques and charging for powerful models—the approach taken by top US labs including OpenAI and Google—prioritized short-term advantage over more durable success. Making his models entirely accessible to the public, and largely free, was the most efficient way for DeepSeek to accelerate adoption and get startups and researchers building on its tech. The hope was that this would create a flywheel of product consumption and feedback. As DeepSeek wrote in the announcement of its first publicized LLM almost two years ago, quoting the inventor of open-source operating system Linux: “Talk is cheap, show me the code.”

“Basically they don’t need the money. With all the hype around the Six Little Dragons, people are throwing money at them” On a cloudy Sunday in April at Hangzhou’s bustling Xiaoshan International Airport, digital billboards touting AI services from Alibaba, ByteDance and Huawei greet arrivals. A humanoid robot with blue hair welcomes passengers with a wave inside the modern terminal. Outside, an autonomous-vehicle startup has been testing small self-driving trucks for transporting cargo around the tarmac. For all the noise around DeepSeek, Westerners seem to forget it’s just one of many AI dragons rising across China’s numerous Silicon Valley equivalents. In Hangzhou alone, a megacity with a population of 12.5 million, DeepSeek belongs to an elite group of tech startups known as the Six Little Dragons.

In the scenic West Lake district there’s Game Science, the red-hot studio behind Black Myth: Wukong, a bestselling action game heralded for using machine learning techniques to make its computer characters more lifelike. Not far away are two robotics powerhouses and a unicorn focused on 3D-spatial software. Also nearby is Zhejiang Qiangnao Technology Co., which is known as BrainCo and best understood as a China-backed version of Neuralink Corp. It can be traced back to a startup incubated at Harvard University by a Chinese-born Ph.D. student, Bicheng Han, and is now developing bionic limbs and technologies for brain activity to control computers, at its affiliate lab in Hangzhou. One of BrainCo’s AI-powered prosthetic hands is currently on display at an exhibition center in China Artificial Intelligence Town, another emerging tech hub in Hangzhou.

In recent weeks, BrainCo leaders have given tours at the exhibit, according to someone who attended a session. The attendees often want to invest, but apparently these brainiacs haven’t sounded too desperate for outside capital. “Basically they don’t need the money,” says a fund manager who took the tour. “With all the hype around the Six Little Dragons, people are throwing money at them.”

Standing quietly behind all these startups is the government of President Xi. Generative AI, robotics and other high-tech ambitions are driving a state agenda that above all else seeks domestic “self-reliance and self-strengthening,” as Xi phrased it during a recent Politburo meeting, according to China’s official Xinhua News Agency. “We must recognize the gaps and redouble our efforts to comprehensively advance technological innovation, industrial development and AI-empowered applications.”

The dragons are listening, and not all of them are so little. The main campus of $300 billion conglomerate Alibaba, a sprawling property with its own lake, is in an area of Hangzhou about 40 minutes west of West Lake by car. The company recently pledged $53 billion toward constructing more AI data centers in the next three years, and it’s said its latest Qwen3 flagship models rival DeepSeek’s performance and cost efficiencies. Outside China, Alibaba is usually thought of as an e-commerce business, but its faster-expanding AI and cloud unit was spun off in 2022 to a separate hub on the outskirts of Hangzhou. Inside its conference rooms, big screens glow with an “industry insights flash,” updated every 72 hours, detailing the latest achievements of rivals such as DeepSeek and OpenAI. There’s even a weekly updated version in the restrooms, a reminder that AI races on even when nature calls for human technologists.

This April, Ma, the elusive Alibaba co-founder who practically disappeared during the CCP’s crackdown on China’s tech sector almost five years ago, reappeared on the company’s campus to celebrate the 15th anniversary of its cloud division. In a rare speech, Ma said he wants AI to serve humans, not lord over them, according to several people who saw it. Attendees, who also tuned in to the livestream from offices in Hong Kong and Tokyo, say they were pumped about Ma’s triumphant comeback.

It was a reminder that tech rock stars such as Ma are apparently back in the good graces of the CCP—and being joined by up-and-comers like Liang—even as the shine wears off tech leaders in the US. There’s a swelling national pride in China, which is eager to show it can overcome Western obstacles. George Chen, the Hong Kong-based managing director of policy consultant Asia Group LLC, says top Chinese engineers have begun returning home after stints in the US at Apple, Google, Microsoft and other leading companies. While hostility from the Trump administration is part of that, they’re also being pulled by the feeling that the real action may be shifting east. “Silicon Valley is no longer an attractive place for work for Chinese talent,” Chen says.

Kai-Fu Lee, the founder of another Chinese unicorn, 01.AI, goes a step further. A veteran of Apple, Google and Microsoft himself, Lee says the next generation of talent isn’t following his path through US companies before building their own in China. “These young AI engineers are largely homegrown,” he says. “DeepSeek’s success, along with the success of other new AI startups, is motivating more young talent to be a part of China’s AI renaissance.”

Liang (center) at a symposium in Beijing in February.Photographer: Florence Lo/Reuters

No tech company in China today conjures as much pride as DeepSeek. While visiting Hangzhou with his family in April, Kirby Fung, a 27-year-old computer scientist from Canada, took his family for a tour of Liang’s alma mater, Zhejiang University. Fung had done an exchange program there and wanted to show his grandparents and younger brother that he studied at the same place as Liang. “It’s really cool to explain to my friends back in Canada that the guy who made DeepSeek went to my school,” Fung says.

Tourists and social media influencers also regularly descend on DeepSeek’s headquarters, based in a four-tower complex overlooking China’s famous Grand Canal. The tourists look for signs of Liang at the local shops, including an upscale hot-pot spot in the DeepSeek building where staffers sometimes eat. (The hostess has to break the news that he never stops by.)

People who know Liang say he splits his time between Hangzhou and DeepSeek’s Beijing office, on the fifth floor of a glass tower in a local tech hub. There, twentysomething coders grind at height-adjustable desks, and the pantry is stocked with energy drinks, Kang Shi Fu instant noodles and latiao sticks. There’s a whiteboard where employees can scribble requests for additional food. “I got a bit fat after having lunch and dinner there for months,” says one recently departed researcher.

Liang rarely agrees to meetings with outsiders, sometimes even appearing as a hologram projection for the few he accepts. He spurned an invitation to this year’s influential Paris AI Action Summit, an event that attracted OpenAI’s Altman, Alphabet Inc. and Google CEO Sundar Pichai and a slew of prime ministers and presidents.

While China celebrates DeepSeek, the US treats it like an unfamiliar organism that’s mysteriously shown up in the water supply, examining it for signs of whether it’s benign or malignant. Critics have accused DeepSeek of being controlled by the CCP, ripping off training data from US rivals and contributing to some larger espionage campaign or psyop to undermine Silicon Valley’s AI hegemony. “DeepSeek is a direct pipeline from America’s tech sector into the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance state, threatening not only the privacy of American citizens but also our national security,” says a spokesperson for the US House committee investigating DeepSeek.

DeepSeek, however, has presented itself as no different than any hot startup—the product of “pure garage-energy,” it said in a February post on X. After all, it operates on the same Beijing campus as Google, not far from a Burger King and two Tim Hortons. Just because the broader AI industry didn’t pay much attention to DeepSeek until now doesn’t mean something shady is happening behind the scenes. “The AI world didn’t expect DeepSeek,” says Arnaud Barthelemy, a partner at VC firm Alpha Intelligence Capital, which has invested in OpenAI and SenseTime. “They should have.”

Barthelemy says the real lesson to take from DeepSeek is how effectively Chinese tech companies are turning the constraints they operate under into a strength. “There are plenty of smart minds in China who did a lot of smart innovation with much lower compute requirements,” he says.

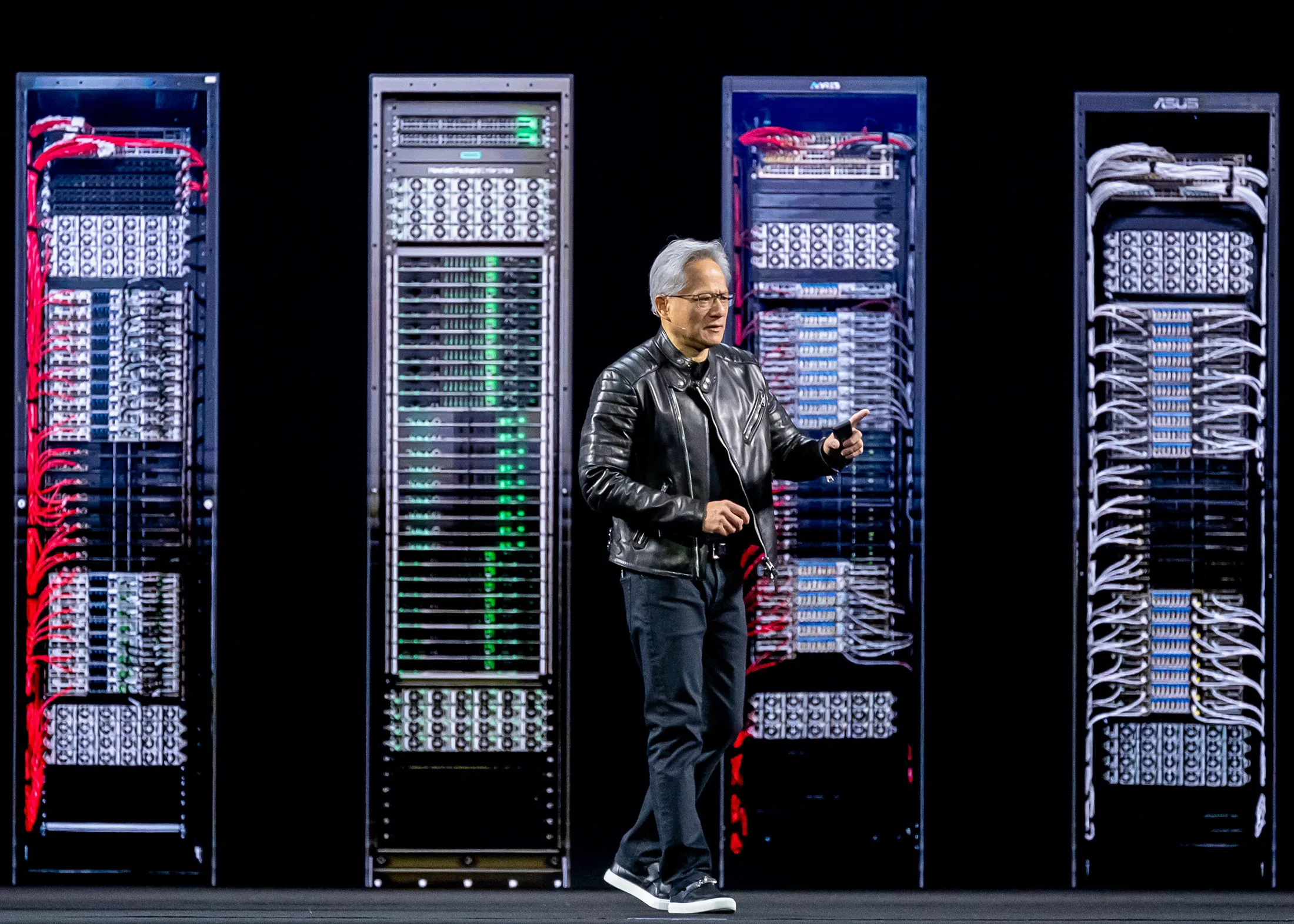

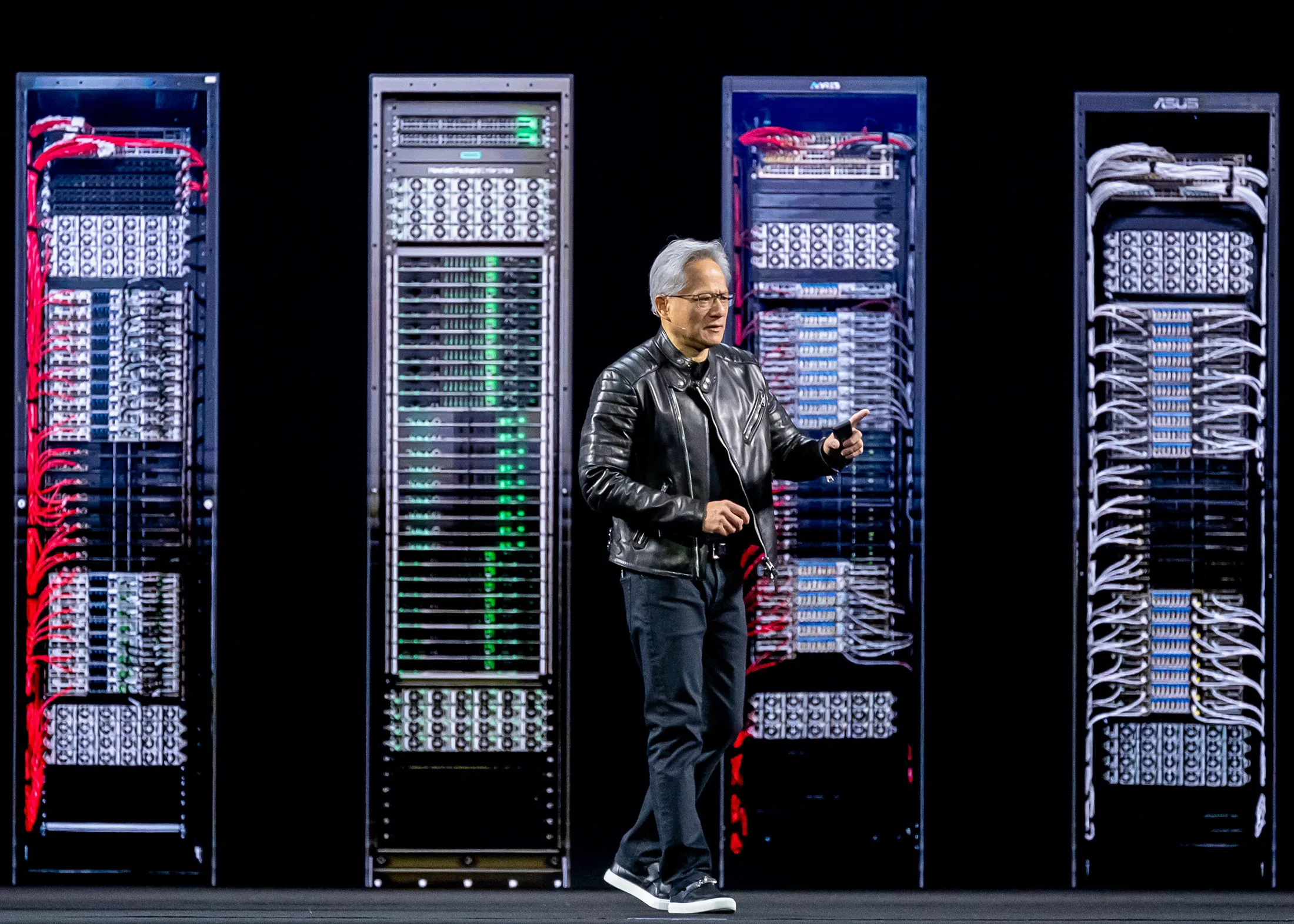

Indeed, in May 2023, coincidentally the same month DeepSeek was established, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang told Businessweek that the US’s overregulating China will only incentivize it to out-innovate those getting in its way. Describing economic influence as an effective tool of national security, he stressed that the unintended consequences of government interventions would be severe. “To be deprived of one-third of the technology industry’s market has got to be catastrophic,” he said, referring to the risks of limiting US tech exports to China. “They are going to flourish without competition. They will flourish, and they will export it to Europe, to Southeast Asia.”

“You have to be mindful of how far you push competition,” Huang continued. “All of a sudden the response is very unpredictable. People who have nothing to lose respond in ways that are quite surprising.”

Nvidia’s Jensen Huang has argued that export controls could end up strengthening China.Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

There’s still controversy about one important part of DeepSeek’s story: how much it actually spent to build its models. In a widely cited report, US research firm SemiAnalysis estimated that High-Flyer and DeepSeek likely had access to clusters of around 50,000 of Nvidia’s top-of-the-line H-series GPUs, worth $1.4 billion, which they’ve mostly kept hidden from the public. The bulk of this infrastructure, SemiAnalysis said, included GPUs that were conceivably export-compliant. (The US allowed Nvidia to sell some chips—the H20 and H800—to China that it modified to limit performance so they adhered to White House restrictions.) But the consulting firm also claimed DeepSeek had access to an additional 10,000 of Nvidia’s bleeding-edge H100 chips, which the US government had banned for sale to China.

Three ex-employees vehemently deny these claims, saying DeepSeek had fewer than 20,000 GPUs consisting of older Nvidia chips and export-controlled ones. “They are spreading lies,” Bo Liu, the Ph.D. candidate, says of SemiAnalysis. The research firm says it stands by its report.

What’s not in question is whether DeepSeek would welcome access to the scale of computing power that US tech companies have. The company seems confident it could do much more with it than Silicon Valley. “The reality is that LLM researchers have an enormous appetite for computational resources—if I were working with tens of thousands of H-series GPUs, I’d probably become wasteful too, running many experiments that might not be strictly necessary,” says one of the former DeepSeek employees. But access to more resources is a problem that China’s technologists would be willing to deal with. “I wish we Chinese companies could have 50,000 GPUs one day,” says the departed researcher, who’s since joined another open-source AI lab in Beijing. “Want to see what we could achieve?” — Austin Carr, Saritha Rai and Zheping Huang, with Luz Ding, Claire Che, Matt Day and Jackie Davalos |