What if Trump picks an inflation nutter for Fed chair?

With US checks and balances on the retreat, it is unwise to be an optimist

Ever since the benefits of central bank independence caught on in the 1990s, one legitimate concern has been that officials might not have the public’s best interests at heart. Former Bank of England governor Lord Mervyn King insisted that UK inflation targets were symmetrical around a 2 per cent target so that central bankers had no incentive to become “inflation nutters”, determined to always reduce inflation to its lowest possible level. The same thinking provided the foundation for the US Federal Reserve’s dual mandate of seeking maximum employment and stable prices

Donald Trump does not care much for established monetary theory or practice. He wants to replace Jay Powell as chair of the Fed when his term ends next May with a low interest rate guy. “Whoever’s in there will lower rates,” the US president told reporters in June. “If I think someone is going to keep rates where they are, I’m not going to put them in.” His choice will prioritise low interest rates and seems likely therefore to be some sort of inflation nutter.

The successful candidate will now have to demonstrate he is signed up to Trump’s belief that low interest rates are the reward for a booming economy and should fall to 1 per cent immediately. Although Trump’s nomination for the vacant Fed governor position, Stephen Miran, has the required deference, that does not appear enough. Trump has made it clear Miran is just “a temp”, providing a loyalist vote on the Federal Open Market Committee until the term runs out in January. It is still possible he becomes chair.

Meanwhile, the beauty parade of the other leading candidates has begun. When the essential requirements for the job have been expressed so clearly, it is not surprising that the current top candidates all want lower interest rates. Former Fed governor Kevin Warsh has ditched his reputation for being hawkish and now sees the benefits of looser monetary policy. “He’s very good”, Trump told CNBC last week.

The director of the White House National Economic Council, Kevin Hassett, received similar praise and has been happy to go on air to rough up Powell, praise tariffs and defend the president’s firing of the Bureau of Labor Statistics chief. Loyalty is his middle name. Fed governor Christopher Waller used to believe that the Fed had to see progress in disinflation before cutting rates, saying the worst thing it could do would be to cut and then have to reverse the decision. He dissented from the majority wait-and-see decision at the July FOMC meeting and voted to cut rates. None of these candidates will be seen as independent of the US president. The question is how the Fed, as an institution, will respond to having an inflation nutter in the top job.

For the most optimistic scenario, look to Brazil. Early last year, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was at loggerheads with the Banco Central, accusing it of taking political decisions to hurt his government and keep interest rates high. In May 2024, his appointees on the policy committee were outnumbered by those selected by former president Jair Bolsonaro in a knife-edge vote on the scale of interest rate cuts. But once he had appointed a political ally as governor, Lula changed tune and recognised the threat of inflation. The committee voted unanimously to raise rates in September 2024. Lula said if his pick for governor thought tighter monetary policy was needed, it must be true. The central bank has voted unanimously to raise rates another six times since.

Trump has an inkling that his nominee might get captured by the Fed and does not like the idea. He understands that the people currently sucking up to him might not be the real deal. “Sometimes they’re all very good, until you put them in there, and then they don’t do so good,” he told CNBC.

Alternatively, policy differences could be laid bare in public once Trump has his pick. Fed governors and regional Fed presidents can outvote the chair and, for now, Trump cannot fire them. The part of me that loves transparency would welcome this, but it is risky. Trump can make life difficult for Fed governors and regional presidents do not have absolute constitutional security in their roles. US central bank independence could die entirely.

More likely is that a dovish Fed chair gets his way by moving gradually to loosen policy and please the president. When you are talking about a quarter point here or there, it is impossible to take a categorical stance that the decision is wrong. These are fine judgments and even the best people can bend in a storm. Since monetary policy has its effect in the future and stuff happens in between, it is relatively easy to blame other things for inflation and deny you made a policy error.

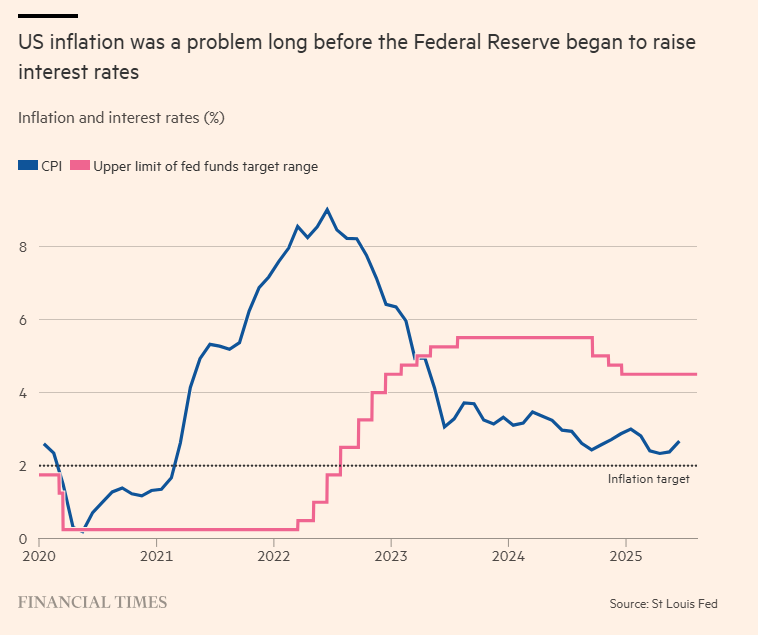

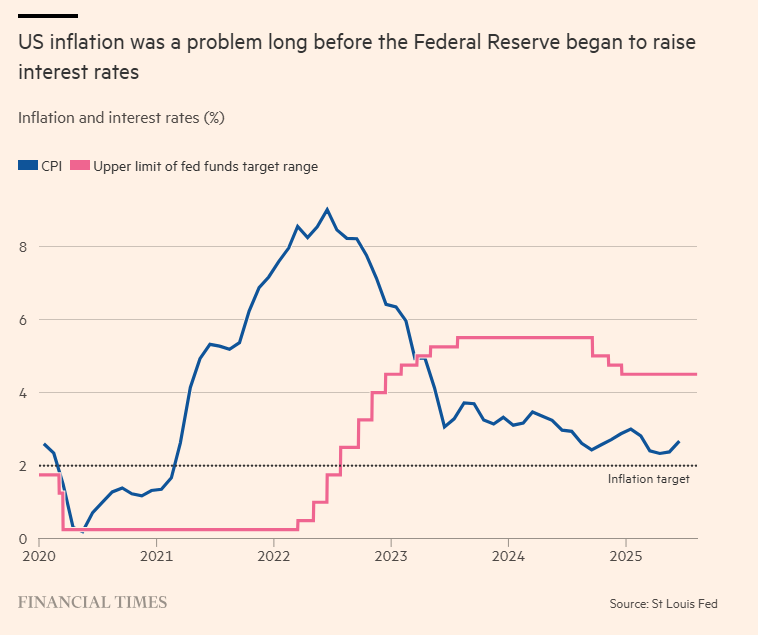

Financial markets will also celebrate interest rate cuts at first. But the longer we lack monetary independence in the US and have a Fed always keen to let doves fly, the more the risks of higher inflation, higher long-term borrowing costs and a loss of confidence in the dollar rise. As 2021 showed, higher inflation can persist for some time while officials predict it is transitory before reality bites. We are going to get a servile Fed chair. The initial transition is likely to be smooth and that is almost certainly bad news for all of us.

chris.giles@ft.com

ft.com |