A Forgotten Scientist May Have Cracked Life’s Origins on Earth 50 Years Ago, But the World Ignored His Discovery

A Forgotten Scientist May Have Cracked Life’s Origins on Earth 50 Years Ago, But the World Ignored His Discovery

A forgotten biochemist’s radical model for the emergence of life is making a surprising comeback—half a century after it was first dismissed. As scientists race to define what life really means, particularly in the context of astrobiology and synthetic biology, a theory devised in Cold War-era Hungary is quietly reshaping the global conversation.

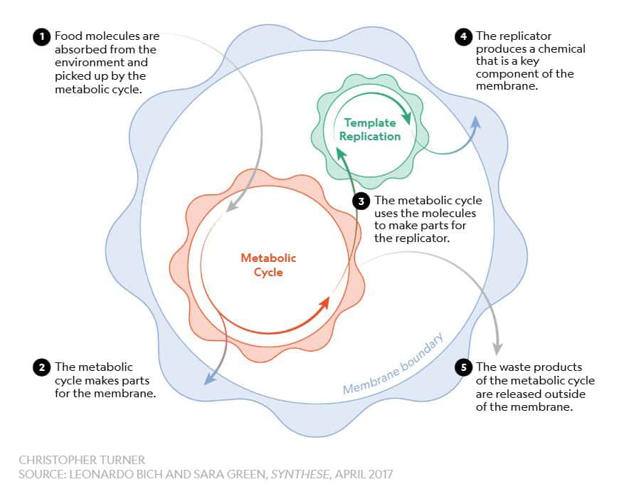

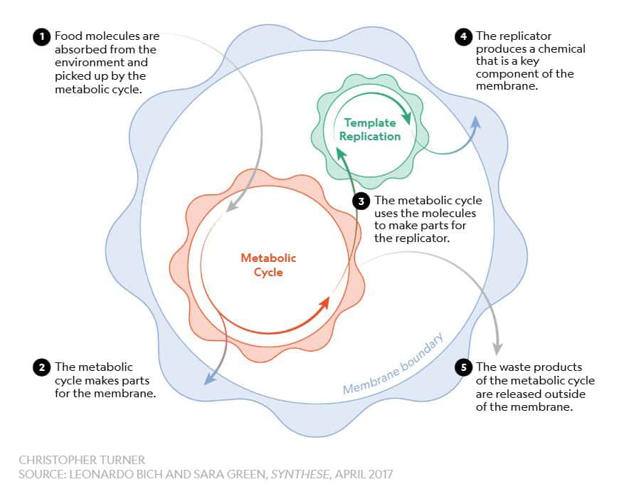

A Theory Decades Ahead of Its TimeIn 1971, Tibor Gánti, a Hungarian scientist working under Soviet rule, proposed a bold answer to one of biology’s biggest questions: what is the simplest form life could take? His concept, known as the chemoton, published in the Journal of Theoretical Biology, suggested that life must comprise three interdependent components: a self-sustaining metabolism, a system for storing heritable information (such as genes), and a boundary separating it from the environment.

For Gánti, these weren’t optional traits—they were essential. “Without all three,” he wrote, “you have chemistry, not biology.” His work, however, remained mostly inaccessible. His key book Az Élet Princípiuma (The Principles of Life) was only published in Hungarian and wasn’t translated until decades later.

Today, with scientists exploring protocells, minimal genomes, and the origins of lifebeyond Earth, his once-overlooked model is attracting serious attention.

Western Science Had Other PrioritiesDuring the 1970s and 1980s, the dominant narrative in Western science focused on genetics—specifically DNA and RNA. The highly influential RNA world hypothesis argued that life began with self-replicating strands of RNA, sidelining more integrated models like Gánti’s.

How A Chemoton Works© Daily Galaxy UK

Gánti’s contemporaries, like American theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman, proposed autocatalytic sets of chemical reactions capable of self-replication. German chemist Manfred Eigen, meanwhile, introduced the concept of hypercycles, linking genes and proteins in evolutionary loops. Gánti’s chemoton anticipated elements of both models but added a crucial third component—a membrane, which neither addressed.

According to Hungarian evolutionary biologist Eörs Szathmáry, co-author of The Major Transitions in Evolution, Gánti was fiercely defensive of his model and difficult to collaborate with—factors that likely slowed its adoption.

Fresh Lab Evidence Revives an Old IdeaIn recent years, however, laboratory evidence has increasingly aligned with Gánti’s vision. In 2023, a research team led by Sara Szymkuc at the Polish Academy of Sciences published a study showing that just six simple chemicals, including water and methane, can yield over 30,000 biologically relevant compounds, including precursors to RNA and proteins. This suggests the origin of life may not have required improbable molecular coincidences.

At the same time, synthetic biologists such as Jack Szostak at Harvard Medical School and Taro Toyota at the University of Tokyo have built protocells—simple membrane-bound structures capable of growth and division. These structures mimic features of living cells without relying on DNA, echoing the chemoton’s principles.

Petra Schwille, group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry, notes that modern protocell research is “deeply inspired by Gánti’s integrated systems thinking.” Her lab, among others, is working to build cell-like systems from scratch using modular biochemical parts.

Life, Defined for Earth—And ElsewhereBack in 1994, a committee at NASA proposed a now-famous working definition of life: “a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution.” But Gánti’s chemoton offers a more structured, testable framework. By combining metabolism, information storage, and compartmentalisation, it describes life as a functioning whole—not just a molecule that can copy itself.

That’s exactly the kind of model needed for astrobiology, where researchers are hunting for life that may never have used DNA or RNA. On icy moons like Europa or Enceladus, or in the atmosphere of Venus, the chemoton’s flexible definition of life could help detect organisms fundamentally different from those on Earth. |