Pacific NW Magazine

How Washington was able to turn back coal, and what it means now

The coal terminal project in Longview was proposed for this site along the Columbia River. Opponents contended the shipping of coal by rail and boat risked pollution in the form of coal dust and carbon dioxide. Proponents dismissed those claims and said the port project was needed for the jobs it would create. The proposal failed. (Millennium Bulk Terminal)

Oct. 4, 2025 at 6:00 am Updated Oct. 4, 2025 at 6:00 am

By

Bob Wyss

Editor’s note: This is an edited excerpt from Bob Wyss’ new book, “Black Gold: The Rise, Reign and Fall of American Coal” (University of California Press, $28.95). The book describes coal’s central role in America’s culture, society and environment in sparking the Industrial Revolution and now contributing to the climate crisis. The efforts to build an export coal terminal in Longview are central to understanding coal’s impacts on America’s future.

THE MULTIMILLION-DOLLAR venture began with a lie. Few denied it. Even those behind the venture had to admit a mistake had been made.

In November 2010, the Cowlitz County commissioners approved a plan submitted by an Australian-based coal company to build a coal export plant on the Columbia River. The proposed Millennium Bulk Terminal in Longview would receive 5.7 million tons of coal each year from the Powder River Valley in Wyoming and Montana. Millions would be spent to clean up the industrial site, where 50 years of aluminum forging by the previous owner had contaminated soil and groundwater. The new terminal would ship the coal to customers in Asia.

Three months later, memos and emails surfaced suggesting that the port would handle 20 million to 80 million tons a year. In addition, some of the commentary written by coal executives discussed a strategy to hide the higher numbers. They wrote that they did not want to give the impression that they had been misleading officials. Opposition had already begun to build on the part of major environmental organizations, local grassroots groups and concerned citizens.

Railcars carried coal from a plant in Rawlins, Wyo., in 2014. In a sign of how seriously the coal industry took a proposed coal terminal in Longview, Matt Mead, the governor of Wyoming, traveled to Longview in 2013 to make the case directly to Washington citizens, urging them to allow the new coal plant. They didn’t. (Jim Wilson / The New York Times)

Railcars carried coal from a plant in Rawlins, Wyo., in 2014. In a sign of how seriously the coal industry took a proposed coal terminal in Longview, Matt Mead, the governor of Wyoming, traveled to Longview in 2013 to make the case directly to Washington citizens, urging them to allow the new coal plant. They didn’t. (Jim Wilson / The New York Times)

“It’s pretty black and white,” said Les Anderson, a Longview resident. “I think they lied to us.”

Company officials tried to deflect the criticism. “When any business develops a site, they’re going to look at all kinds of things,” Joe Cannon of Millennium said. “Different people speculate on different things, and they send emails.”

Ted Sprague, president of the Cowlitz Economic Development Council and a supporter of the project, said that in looking back he felt coal proponents had made a key error. “It would have been difficult for anyone to repair those hurt public feelings,” he said.

A month later, the company withdrew its application to build the terminal. A Wall Street Journal headline proclaimed that “Coal Foes Claim Victory,” but Millennium officials vowed to refile and fight for the port project.

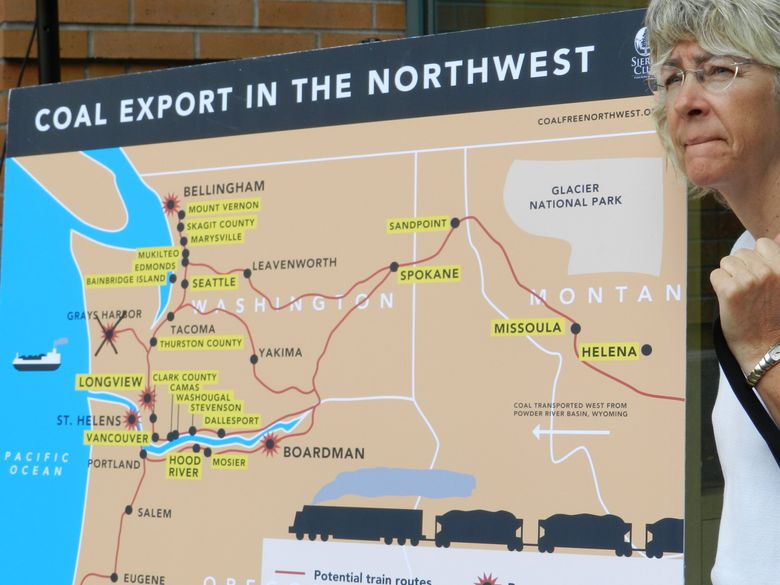

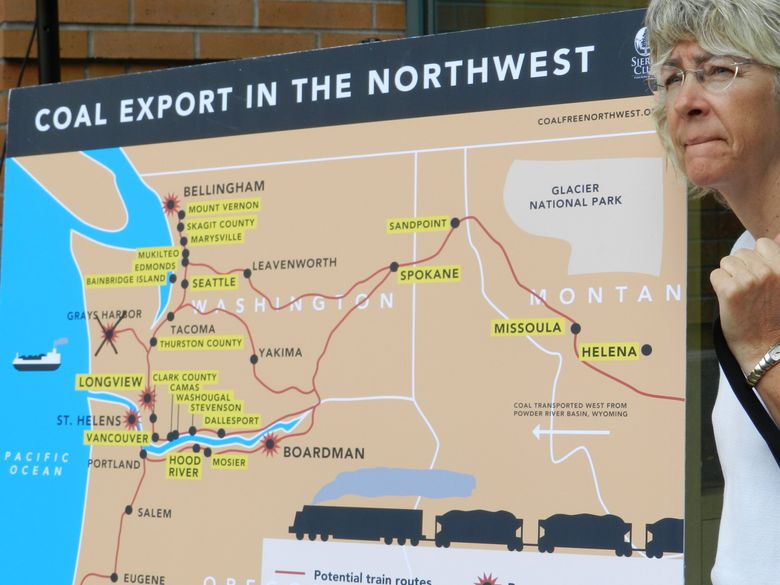

A map showed actual or proposed Northwest coal terminals in 2012. (Courtesy Power Past Coal)

A map showed actual or proposed Northwest coal terminals in 2012. (Courtesy Power Past Coal)

COAL IN THE 21st century is at the nexus of a quarrel that threatens the world. It has an ally in President Donald Trump, who wants the ailing industry that he calls “clean” and “beautiful” to be revived with the fuel shipped overseas.

Coal survived a century of smothering toxic clouds over smoke-filled cities, and today it must deal with its impact in producing global warming. Emissions from burning coal are a major reason the planet’s temperature for the past decade has been the highest in recorded history, resulting in increased droughts, severe storms, major fires and rising sea levels. U.S. coal use has been falling significantly, and environmental groups have vowed to bring a permanent end to coal in America; the Sierra Club has a campaign titled “Beyond Coal.”

AUTHOR EVENTS

Oct. 9: 6:30 p.m., Paper Boat Booksellers, 4522 California Ave., Seattle

Nov. 4: 7 p.m., Third Place Books, 17171 Bothell Way N.E., Lake Forest Park

Nov. 7: 6 p.m., Village Books, 1200 11th St., Bellingham

This site in Longview was the proposed home of the Millennium Bulk Terminal. After a years-long battle, the state of Washington defeated the effort to bring a coal plant to the state. (Alan Berner / The Seattle Times, 2013)

A proposed coal terminal in Longview would have exported up to 44 million metric tons of coal annually to Asia. Proponents of the plan originally said in 2010 that 5.7 million tons of coal would be shipped to the facility. When a report emerged that the number would be between 20 to 80 million tons, the plan was dropped and later brought back. The new proposal in 2012, which eventually failed, acknowledged the number would actually be 44 million tons. (Millennium Bulk Terminal)

The coal industry desperately fought back, referring to the “war on coal” that decried the cost of lost jobs and the economic decline of coal states. Searching for new customers, the industry mounted an audacious plan to sell the fuel to more willing buyers in China, Japan, South Korea and elsewhere. Up and down the West Coast, export terminals were proposed from Vancouver, B.C., to Oakland, Calif., that would ship up to 150 million tons of coal annually. Many believed that among the proposed terminals, Longview stood the best chance of success.

Eleven months after Millennium withdrew its proposal, it returned in February 2012 with a plan significantly more expansive. Now, the proposed coal terminal would cost $600 million and export 44 million tons annually, nearly eight times what had been envisioned. Brett VandenHeuvel, head of the environmental organization Columbia Riverkeeper, said local and public officials should trust the new plan as far as one could throw 44 million tons of coal.

This time, Millennium came better prepared. Arch Coal, the nation’s second-largest coal company, owner of the colossal Black Thunder coal mine, joined Millennium as a partner. Situated 1,200 miles away from Longview in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, an area once roamed by the Sioux, the mine for many years was ranked as the world’s largest coal operation. In its first 50 years of operation, it shipped a record-setting 3 billion tons of coal.

Longview had its own distinctions. In the 1920s, the Long-Bell Lumber Company of Kansas City and its president, R.A. Long, planned every building, street and sidewalk in creating Longview. A local historian wrote that Longview “was begun as a city — a synthetic city, some called it — but in a careful almost loving way by an aging man who mixed his dreams with his dollars.” Long did much more than pour in $9 million in company funds (more than $150 million today). He also built two lumber mills, a six-story steel and masonry hotel, parks, schools and, eventually, houses. The lumber company is no more and the city evolved and grew to 38,000, aided by a port on the Columbia River near where Lewis and Clark camped more than 200 years ago.

INITIALLY THERE APPEARED to be broad support for the Millennium project. Polls taken in the summer of 2013 showed that 60% of Washington residents favored the coal port. Supporters included most city and county elected officials, the local daily newspaper and a surprising alliance of business and labor organizations. Newspaper and television commercials touted the project, and Millennium sought to embed itself in the community, hosting annual picnics and distributing grants of tens of thousands of dollars to worthy civic and charitable groups.

The opposition, however, had only begun to build.

Jay Inslee, then Washington’s newly elected governor and known for his efforts on clean energy and climate change, later based his failed 2020 campaign for the presidency on the issue. Many officials and supporters in his administration echoed the governor’s concern. Many opposed shipping a cargo that posed such a global environmental threat to other nations. As Steve Stuart, a county commissioner in Vancouver, Wash., said, “We can no longer stick our heads in the sand and pretend short-term financial gains are worth the health of the planet.”

Then-Gov. Jay Inslee spoke at a news conference in 2018 in SeaTac, announcing plans to sue the Trump administration over its proposal to dismantle Obama-era pollution rules that would have increased federal regulation of emissions of coal-fired power plants. Inslee, who was elected governor in 2012, fought the proposed coal export plant in Longview. (Elaine Thompson / The Associated Press)

Then-Gov. Chris Gregoire, right, with Climate Solutions policy director K.C. Golden, left, and Montana Gov. Brian Schweitzer in a 2011 meeting in Seattle. The governors discussed the controversial proposal to build a coal terminal just west of Longview, a plan Schweitzer favored. (Elaine Thompson / The Associated Press)

Coal export supporters responded that the United States had been shipping coal overseas for decades, far more than the 44 million tons that would come out of Millennium. Anywhere from 75 million to 125 million tons were shipped out of small ports on the West and East coasts. In addition, Arch Coal exported more coal from a port in Vancouver, B.C.

Rep. Debra Lekanoff, D-Bow, spoke on the House floor in 2019, at the Capitol in Olympia. The Washington House passed a measure in 2019 seeking to eliminate fossil fuels such as natural gas and coal from the state’s electricity supply by 2045. In 2017, the state had denied a water permit for a proposed coal export plant in Longview. It was the first of several legal defeats that eventually doomed the proposal. (Ted S. Warren / The Associated Press)

Millennium Bulk Terminal CEO Bill Chapman, left, discussed a proposed coal export terminal with former Gov. Mike Lowry and Millennium Vice President Peter Bennett during Lowry’s visit to the site in 2015. In 2017, the state ruled against approving a water permit, which led to the demise of the project. (Shari Phiel / The Longview Daily News)

Activists worked to build a massive grassroots movement. “We had ranchers from Montana and Wyoming, local businesspeople, pastors, grandmothers, teachers and other members from the community,” said Lauren Goldberg, an attorney at the time for Columbia Riverkeeper. “We built on existing relationships, on core groups, using existing networks.”

A public hearing in Longview in 2016 drew plenty of protesters against a proposed coal terminal there. (Courtesy Power Past Coal)

Protesters of all ages at a rally in Portland in 2014 voiced their opposition to a proposed coal terminal in Longview. (Alex Milan Tracy)

Surprisingly, much of the concern eventually focused less on climate change than on the number of additional coal-laden trains passing through towns in the region and the coal dust they would produce. Many hated these trains, which already seemed to shut down roadways interminably. Newspaper advertisements purchased by the project’s supporters, displaying a massive haze of coal dust coming from coal cars, riled the public even more.

The claims, which often went to extremes, drove terminal supporters crazy. “I’m not an extremist, but I saw some things that made me sick to my stomach,” Sprague said.

ALL THE RANCOR and fervor of the debate coalesced in a series of public hearings in 2013 and 2016. They were anything but staid government proceedings. The public hearings were more like carnivals or sports rallies, complete with barkers and cheerleaders, often armed with placards rallying the multitudes. Opponents wore red T-shirts, handed out baked goods and carried signs such as the 12-foot-tall inflatable globe that said, “Coal is poison.” Supporters donned blue T-shirts, hosted rallies that featured barbecue cuisine, and bused in hundreds. Despite the pep-rally atmosphere, the hearings hosted by local, state and federal officials in huge, cavernous rooms were orderly and peaceful.

An empty train in the foreground awaits loading while a full coal train in the background starts to make its journey east from the Black Thunder coal mine near Wright, Wyo. The mine is one of the largest in the world and would have sent coal to a proposed plant in Longview. That plan never materialized. (J.B. Forbes / St. Louis Post-Dispatch / TNS)

Some of the numbers that came out of these meetings were impressive. When the first set of hearings was finished, more than 50,000 comments had been received. After the second round, a quarter million had expressed their opinion. The official assessment of the project numbered more than 3,000 pages. Tens of millions of dollars were spent, especially by the proponents.

By 2017, the Millennium project stood alone, all other West Coast proposals dying or gone. “We weren’t going to sell our souls here,” said Jack Fleck, a retired engineer in Oakland, when his community killed its proposal. “Whatever the economic benefit would’ve been, it wasn’t worth destroying our planet.”

Eric Ross led a protest in downtown Tacoma in 2013 against a proposal to build a plant in Longview that would have exported coal from Wyoming and Montana to Asia. The plan did not pass and the project was scrapped. (Alan Berner / The Seattle Times)

Eric Ross led a protest in downtown Tacoma in 2013 against a proposal to build a plant in Longview that would have exported coal from Wyoming and Montana to Asia. The plan did not pass and the project was scrapped. (Alan Berner / The Seattle Times)

Demonstrators marched along Pacific Avenue in downtown Tacoma in 2013 in opposition to a proposed coal terminal in Longview. (Alan Berner / The Seattle Times)

The stakes were high, and on Sept. 26, 2017, the state of Washington announced a major decision on the Millennium project. It was a blockbuster, monumental and unprecedented. The Department of Ecology took what had once been an obscure permit, Section 401 Water Quality Certification, and broadened the scope of its inquiry. It concluded that the terminal would adversely cause a sweeping, vast range of environmental impacts. The proposed port would negatively affect air quality, vehicle and vessel traffic, railroad safety and capacity, noise levels and ultimately social, community, cultural and tribal resources. “There are multiple insolvable problems with the proposal,” wrote Maia D. Bellon, director of the Department of Ecology.

Terminal supporters were stunned and upset by the scope and breadth of the defeat.

In a statement, Bill Chapman, president of Millennium, said that the agency “disregarded decades of law defining the Clean Water Act.” He called the agency biased and unfair in the way it assessed the facts, and Millennium officials predicted the decision would never hold up when they appealed in the courts.

Conservation groups opposing the export project had urged the Department of Ecology to make a strong statement in the water quality permit. Often such statements were cursory and brief. “Here, they looked at it more broadly than they had done before,” said Jan Hasselman, an attorney for Earthjustice, one of the opponents. “They found a number of distinct adverse environmental impacts.”

A rally in Vancouver, Wash., in 2016 drew protesters against a proposed coal export plant in Longview. (Bill Purcell / Courtesy Power Past Coal)

Young people were part of a crowd in Portland in 2014 to protest a proposed coal export plant in Longview. (Alex Milan Tracy)

THE RULING HAD ramifications nationally. The first Trump administration, citing the Department of Ecology ruling, adopted new rules sharply limiting the breadth of a state’s authority in issuing future permits. Republicans in Congress decried the decision and worked to amend the Clean Water Act to prevent further decisions against energy projects. The congressional efforts failed, and the Trump rules were thrown out by the incoming Biden administration.

The water permit, only one of 23 the export project needed, did not end Millennium’s fight with the state and in the courts. In January 2018, the company sued Inslee, accusing his administration of violating the U.S. Constitution by illegally embargoing Montana and Wyoming coal from coming into Washington. This cascaded into a legal donnybrook of politically charged accusations. Six coal-producing states that were allied with Millennium filed briefs, with California, New York and four other states opposing. “Gov. Inslee and his allies don’t like coal,” charged Montana Attorney General Tim Fox. “Fortunately for Montana and Wyoming, the United States Constitution prevents such baldfaced discrimination.”

Was it all political rhetoric or had Washington gone too far in restraining a legitimate business? It would take the U.S. Supreme Court to decide in a very brief announcement from the justices on June 28, 2022. The court would not hear an appeal filed by Wyoming and Montana against the state of Washington. It was the last of several cases that Millennium had lost. As legal experts had pointed out, this had always been a longshot — Washington had a constitutional right to prevent a company from selling coal within its state.

“The coal industry’s assault on the Pacific Northwest is over,” Hasselman, the lawyer for Earthjustice, declared in the aftermath. Later, in an interview, he expanded. “This was their Hail Mary, to export coal to Asia, and it failed.”

Arch Coal, like many coal companies, had filed for bankruptcy. It had sold its shares in Millennium; it even removed the word coal from its title, rebranding as Arch Resources, then merged with another company to become Core Natural Resources. Millennium had already given up its lease on the port terminal property after losing multiple legal appeals.

In the aftermath of Millennium’s demise, a 2022 study found that 55 fossil fuel projects involving coal, oil and natural gas had been proposed in Washington, Oregon and British Columbia between 2012 and 2022. Forty were canceled, six approved and nine were still hanging on in hope of receiving the necessary permissions. None of the approved projects involved coal.

The Longview project delivered one clear message — coal was dead in Washington state and perhaps the entire West Coast. “Coal is a four-letter word in Washington state,” said Sprague, of Longview’s economic development office. “I don’t foresee any application for it in the state.”

China, Japan and the rest of Asia remained eager to buy American coal, and producers from the Rockies all the way to Appalachia were eager to supply it. But a massive barrier had been erected and, for the time being, there was no way to breach it.

“This was a collision of basic values in the Pacific Northwest,” said Hasselman. “This is our green corner, and they were trying to turn us into West Virginia.”

Bob Wyss is a Seattle-based writer who covers energy and environmental issues. He is a former reporter and editor for The Providence (Rhode Island) Journal and an emeritus professor of journalism at the University of Connecticut. He can be reached at robert.wyss@uconn.edu

seattletimes.com |