| | | A push for ‘global energy dominance’ puts Alaskan wildlands at risk

Oct. 11, 2025 at 6:00 am Updated Oct. 11, 2025 at 6:01 am

1 of 4 | This polar bear is lounging in the Peard Bay Special Area, critical denning habitat for a signature species of America’s Arctic. These irreplaceable wildlands are threatened by increased burning of fossil fuels, which creates the emissions that are heating our planet. Sea ice that polar bears need is... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2022)

By

Lynda V. Mapes

Special to The Seattle Times

WESTERN ARCTIC, ALASKA — The plane was small, a three-seater, and the bush pilot had filled the tanks in its wings with gas. I slid in next to him, and noticed the knob on the plane’s throttle was carved from ivory of a walrus tusk. Small plane, wings full of gas … but it was too late to wonder about any of that. It was now or never. I chose now.

We lifted off, leaving Kotzebue, a roadless hub community in Alaska above the Arctic Circle, quickly behind. And then the wonder began. Mile upon mile, hour upon hour, we flew north, ever north, and east over the ramparts of the Brooks Range, over gold and green tundra, mirrored with unnamed ponds and lakes, rills and rivers that twined uninterrupted, from the mountains to the sea.

We flew above tundra swans and saw caribou herds, kicking up water from their flying hooves. The golden pelage of a grizzly bear, rippling over its massive body as it ran, our tiny plane a rude startlement in this animal kingdom.

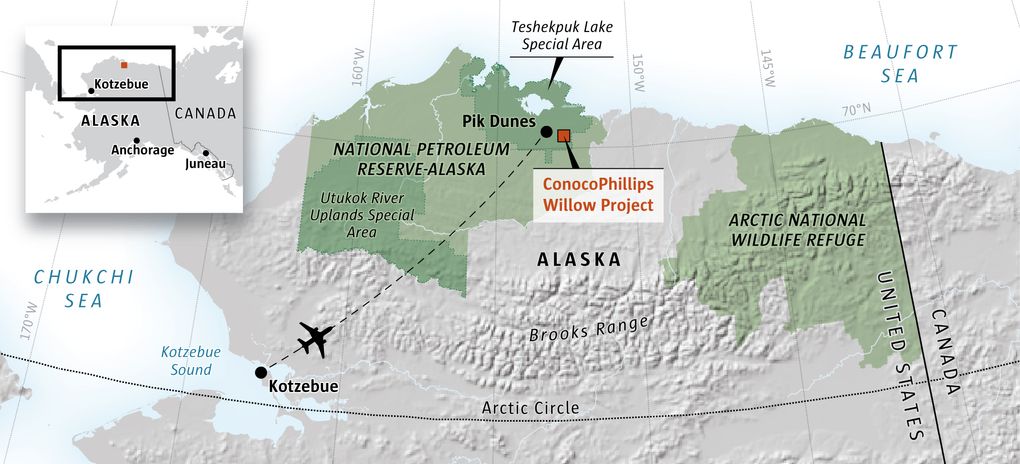

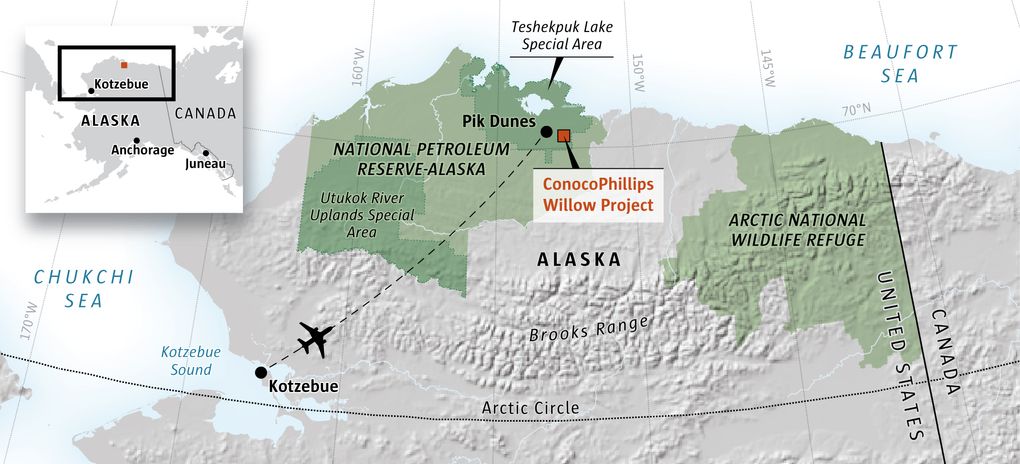

This is the Western Arctic of Alaska, America’s Arctic. Much of it was set aside as a petroleum reserve by President Warren G. Harding in 1923. Congress in 1976 set limits on drilling here, intended to protect the land’s spectacular ecological value. The National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A), at 23 million acres, is the largest sweep of public land in the country, and it has remained largely undeveloped.

Esri, Google (Fiona Martin / The Seattle Times)

Now President Donald Trump in his second term, just as in his first, is calling for full-on extraction of oil and gas here. The Trump plan would open about 82 percent of the NPR-A to oil and gas extraction, including 13 million acres in five designated Special Areas, where protections against drilling were strengthened under the Biden administration. By contrast, Trump, in one of his first executive orders, has called for maximum extraction in a quest for “global energy dominance.”

So, it seemed a good time to come see what’s here, amid Trump’s call for a fossil fuel drilling bonanza.

AT MORE THAN 10 times the size of Yellowstone National Park, the reserve is a place of wonder both expansive and delicate, of wild nature — the grizzly bear, the loon, the caribou and wolverine. A place where nature still make the rules, and the shapes. Not the straight lines of man, with roads, pipelines, airstrips and buildings. But sinuous, undammed rivers, the branching of caribou antlers. A shape repeated in the branching of heather, a delicate beauty that persists in a tundra environment so harsh it can take 30 years, leaf by tiny leaf, to grow a stem as long as my index finger. It is home to nesting grounds of planetary importance for millions of migratory birds. And then there is this: this landscape is a wellspring of wonderment, a place of solace, just knowing it’s still there. A beyond, a place still unto itself.

These polygons in the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, seen from the air, are formed by thawing and freezing of permafrost. The otherworldly shapes are just one feature of a landscape like none other in some of America’s wildest country in... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2022)

The Yellow-billed Loon is an iconic bird of America’s Arctic, with its big wingspan, dagger-like bill and haunting call. Loons… (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2022)

Bearberry flames scarlet amid the tundra above the Pik Dunes, a unique landform in the Teshekpuk Lake Special area. The sands of… (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

We lifted off from Kotzebue, our tiny plane stuffed with gear. We flew for hours, the tracks of caribou made by generation upon generation of their migrations the only marks on the tundra passing mile after mile under our wings. We threaded through a pass in the Brooks Range, and finally, reached our rendezvous point. A camp tiny and remote, just a few tents pitched inside a portable solar-charged electric bear wire, at Pik Dunes, within the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, where Gerrit Vyn, a veteran producer, videographer and photographer for the Cornell Lab’s Center for Conservation Media and his field assistant, Jamie Drysdale, were already working. For four years now, Vyn, 55, of Portland, had been focusing on the Western Arctic, and he was here with Drysdale finishing up four months of field work.

The photos and videos he was sending back from the field, some reposted to the Protect the Arctic campaign, revealed a dazzlement of wonder, including the day some 40,000 caribou ran under and around him, when he suddenly found himself amid the Western Arctic herd’s summer migration, kicking water up onto his lens.

We quickly unloaded our gear, walking across uncountable caribou tracks. Drysdale and Vyn welcomed Kyle Campbell, a second-generation Arctic backcountry guide along with me, like a hero. He’d brought a cook tent and an unspeakable luxury their weight limit hadn’t allowed: camp chairs. Startled at how cold it was, I packed into every layer I had.

“Let’s get out there,” said Vyn, and we headed off into a landscape that stretched to the horizon, shimmering with the white floss of cotton grass.

WE FOLLOWED THE caribou trails as we explored. I sank into the soft tundra often to savor its world, exquisite in miniature: the brilliant leaves of bearberry, crimson against the lush green of moss, and silvery velvet of lichen.

It was the immensity of the space that for once brought our tiny humanness into proper scale on this, our beautiful planet. We were the only people out here, that is for sure. But we were far from alone.

Everywhere we saw the tracks and traces of the animals, so perfectly adapted to this place. A swirl of dry grass of a bird’s nest, a caribou’s jawbone, heather growing through gaps where its teeth once were. The broken shell of a bird’s egg, perhaps dropped by a predator, the pellet of a Snowy Owl, full of tiny bones from its meal. Campbell passed me the sun-bleached skull of a lemming — a favorite of the Snowy Owl — its rows of minute teeth still intact.

The glittering blue ponds set in the tundra, jewel-like, drew us. Ruffled by the wind, then still, their waters reflected the lavender-gray clouds. The tundra ground was wet and soft, forming a padded rim at the water’s edge.

As we explored the shoreline of one pond, we saw the bright green of the aquatic plants that make this such premier habitat for waterfowl. These wetlands all around Teshekpuk Lake on the Arctic Coastal Plain are the most important nesting ground in the Alaskan Arctic for migratory birds.

With the clouds of summer mosquitoes and endless summer days stoking the growth of vegetation, and a vast sponge of tundra wetlands, birds from all over the United States and most of the world’s continents come here to nest. Emphatically creatures of place, no matter where they are headed, this is where these birds are from, and the place to which they must return to raise the next generation, to continue the skeins of their lineage uncounted, year upon year.

Birds beloved in Washington come here: the Brant, Sandpiper, Dunlin and more. Red Knots, a type of sandpiper, have been tagged in Grays Harbor by a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ornithologist, and satellite tracked migrating to the Western Arctic to breed. Vyn photographed one of those tagged birds in the Utukok River Uplands Special Area of the reserve, so many miles away, wingbeat by wingbeat.

A Red Knot was banded in Grays Harbor, and photographed in the Utukok Uplands Special Area — a migration of thousands of miles. While they are distant, these Arctic wildlands are intimately... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

We were startled, walking the shore of a pond, to see in the wet muck a bird track pressed in a rainbow smudge of what looked to be oil. Was it just seeping from the ground here, in this place so sought after for so long for its oil, its minerals, its forests, for whatever it was that people wanted to take from Alaska this time. The bird’s track in this splotch felt totemic, oracular — it was a reminder.

ALASKA HAS ALWAYS held a special place in the American imagination. These wild lands above the Arctic Circle in Alaska, America’s Arctic, have for us long stood as the ultima Thule of wildness, fought over for generations. Teddy Roosevelt — a Republican president from 1901-1909 — was one of the first champions for wild Alaska. The fight over this landscape has been going on ever since.

Most Read Stories

A Semipalmated Sandpiper is snugged into its nest amid the low tundra grasses of the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area, home to vast wetlands that make this the most important migratory bird... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2022)

Caribou pour across a river in their urgent migration on the tundra, the young calling for their mothers and running on knobby legs to keep up. The Utukok Uplands Special Area is home to this... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

Most of the oil and gas development in the Arctic today is centered in Prudhoe Bay, from reserves discovered in 1968 and flowing through the 800-mile-long trans-Alaska pipeline since 1977. The Trump administration hopes to see oil development spread across a much broader swath of America’s Arctic, including the NPR-A and coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge — about 25 million acres in all. Congress in budget legislation passed this summer (by only one vote in the Senate) called for leases for drilling on millions of acres in both the reserve and the refuge, and the administration has put out requests for proposals for seismic testing for oil — work that leaves long-lasting scars on the land.

Expanded oil and gas development is a climate threat of planetary scale — especially in the Arctic, where warming temperatures thaw permafrost, releasing methane, a potent greenhouse gas. The United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization in May announced global climate predictions that show temperatures will be at or near record levels in the next five years, increasing climate risks and impacts on societies. Greenhouse gases from burning more fossil fuel will only increase the pace of warming, stoking wildfires, heat waves, floods and violent storms.

The Arctic already is warming nearly four times faster over the last 40 years than anywhere else on Earth. Permafrost has become a misnomer, and as it thaws, rivers are rusting and turning toxic and acidic with the release of metals in the soil. The seasonal extent of sea ice has been in a decades-long decline, upending the Arctic food web that sustains gray whales and forcing polar bears on land where they risk starvation and conflicts with humans. The Western Artic caribou herd has declined to the lowest numbers in 40 years. While fluctuations in their population are natural, changes in vegetation in the tundra, with warmer temperatures stoking the growth of trees and shrubs, is suspected to be a factor in their decline. Rain on snow events more frequent with warming temperatures encase the lichen that caribou and Dall sheep need under impenetrable ice.

More fossil fuel development is already underway. The Willow oil development at the far eastern edge of the NPR-A was approved under the Biden administration. Developer ConocoPhillips promises to produce 180,000 barrels of oil per day at the project’s peak.

VYN TOLD ME he wanted to show me something, and waved Drysdale and Campbell back to camp. We walked on, my curiosity piqued. We soon reached a small pond Vyn had discovered the day before, a perfect, sheltered place for a family of Red-throated Loons we saw circling in the quiet of its waters. The mother was protective, never far from their two gray, fluffy chicks, the family staying in the middle of the pond. We settled down on the tundra to quietly just listen, and watch.

A push for ‘global energy dominance’ puts Alaskan wildlands at risk

Musk ox are an Ice Age species that thrives in America’s Arctic. Their undercoat is thick and soft and protects them even in plunging temperatures. This musk ox was photographed on Archimedes Ridge in the Utukok Uplands Special Area of the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska, which includes five special areas designated to protect their unique habitat and ecological value. Those protections, and lands, are now at risk as the Trump administration works to open these areas to drilling for oil and gas. (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

Suddenly in a flurry the father arrived, his bill full of a silvery fish. He passed it to one of the chicks, who promptly dropped it. Was this a botched dinner delivery, for which the father must now pay with another foraging round? A practice session for the chick, who, despite dunking under the water to find it, came up empty?

“Would you like to be alone here, feel the experience of being by yourself on the tundra?” Vyn asked me. “I’ll leave you the bear spray. You won’t need it, but it’s the right thing to do.” I watched carefully the notch between hills he walked off to, disappearing from sight, leaving me in my immensity of solitude.

I quieted and settled, just feeling the vast space, its untrammeled expanse, a life-changing gift of this place I knew right then I would carry with me. I watched the mother loon, her delicate face, the elegance of her neck, her perfect plumage, just freshened after her summer molt. She began to call, her inestimably plangent voice a piercing sadness. I thought of her and her family. Would they survive? Would they be here again next year? Would any of this?

I watched the family a long while, then slowly made my way back to camp. That night, rain and wind made my tent shudder. I held the bottle of hot water Campbell had sent off with me for the night deep in my sleeping bag, close to my heart.

1 of 3 | The Colville River Special Area provides the North Slope’s single most important raptor nesting habitat area, with high proportions of the region’s populations of Arctic Peregrine Falcon, as well as other raptors such as gyrfalcon and... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

THE NEXT DAY dawned brilliant. It was time to go see the Pik Dunes that surrounded our camp. A place unique in the Western Arctic, the dunes are a surprise of sand amid the tundra, an almost lunar landscape amid a sea of spongy green wet. How they got here is still being puzzled out, but scientists think the dunes are all that remain of an ancient lake bed, the sands the blowing remnants of Pleistocene soil types.

As we set off, Vyn began following the soft padded track of fox, so many tracks, we must be close to a den. “Fox, fox, fox!” he said with excitement, sighting a fox in the far distance. He headed off toward a bank along the dunes. It was riddled with holes, a warren of dens. Vyn spent hours with what turned out to be a whole family of foxes, photographing their delicate beauty, bushy tails and perked ears. A lone caribou on the dunes kept following him, perhaps trying to figure out just what he was.

The sand showed animal tracks as plainly as fresh snow, and I read the stories all around me written in the sand. The soft pad of grizzly bear, the footprints of ground squirrel, the five-toed walk of wolverine, the delicate foot of a bird.

Slender grasses swept by the wind traced perfect circles in the sand, sundials showing the march of the sun across a sky that stretched open to every horizon. The flowers on tufts of plants keeping their grip in the sand belied their toughness.

The pilot returned too soon, to return us to the rest of our world. The wind had kicked up, and ours would be a low and slow flight back to Kotzebue. As we took off, we saw in minutes, amid what had felt like an endless wilderness, the Willow oil development. There was a road, the first step in ecological unraveling. A bridge, so far to nowhere. Buildings, and a bristle of construction cranes.

Only about 23 miles from the loons.

A Red-throated Loon family shelters in a small pond in the Teshekpuk Lake Special Area. This is the best habitat they will encounter in their lives, which includes wintering grounds in... (Gerrit Vyn / Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2024)

About This Story

This story was supported by the Overlooked & Untold Stories Fund of Braided River. Lynda V. Mapes is a Seattle writer, and a former reporter at The Seattle Times. Gerrit Vyn is a cameraman and producer for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Lynda V. Mapes is a Seattle writer and a former reporter at The Seattle Times. Reach her at lyndavmapes.com. Gerrit Vyn is a cameraman and producer for the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

seattletimes.com |

|