Living Dangerously

Russo-Ukrainian War: Autumn 2025

The Russo-Ukrainian War seems to have been engineered in a laboratory to frustrate people with repetition and analytic paralysis. Headlines appear to be circulating on a choreographed loop, all the way down to the place names. Kaja Kallas at the European Commission recently announced, without a hint of irony, that Europe’s new sanctions package - the 19th one - is the toughest yet. Ukraine’s supporters are insisting that Tomahawk missiles are the weapons system that will finally change the game and break the war decisively in Kiev’s favor - reiterating the same grandiose claims that they made about GLMRS, and Leopards, and Abrams, and F-16s, and Storm Shadows, and ATACMs, and virtually every other piece of military hardware in NATO’s inventories. On the ground, Russia is attacking settlements named Pokrovsk and Pokrovs’ke; it recently captured Toretsk and Tors’ke and is now attacking Torets’ke. The more things change, the more things stay the same.

The analytic frameworks applied to the war have also changed relatively little, buried and obfuscated by the nebulous concept of attrition. On the Ukrainian side, there is continued insistence that Russia is suffering exorbitant losses and straining under the pressure of Ukrainian deep strikes, while Ukrainian setbacks are blamed in large part on the failure of the United States to expand its largesse and give Ukraine everything it needs. Many pro-Russian lines of thinking mirror this and suppose that the AFU is on the verge of disintegration, while the Kremlin is accused of failing to “take the gloves off”, particularly in regards to the Ukrainian energy grid, Dnieper bridges, and dams.

The result is a very strange sort of war. This is an extraordinarily high-intensity ground war. Both armies remain in the field, holding hundreds of miles of continuous front after years of bloody fighting. Both armies are (depending on who you ask) taking unsustainable casualties which ought to lead to collapse soon, and yet Moscow, Keiv, and Washington are all (again, depending on who you ask) guilty of failing to take the war seriously enough. All of this is maddeningly repetitive, and one could be forgiven for tuning out entirely. Even the diplomatic tango between Trump, Zelensky, and Putin, after delivering a few entertaining moments, failed to really move the needle in any discernable direction.

Upgrade to paid

Few would argue that the trajectory of the war changed in an obviously dramatic way in 2025, and it is important to avoid the worn out and clichéd language about “turning points” or “collapse” or any such silly thing. However, 2025 saw several shifts in the war, which will hardly ostentatious or dramatic, are nevertheless very important. 2025 has been the first year of the war in which Ukraine launched no ground offensives or proactive operations of its own. This fact is not only a hint at the threadbare state of Ukraine’s ground forces, but also a testament to the way Russian forces transformed “attrition” from a buzzword into a method of persistent pressure across a variety of axes this year.

In lieu of initiative on the ground, and facing a slow but relentless rollback of their defenses in the Donbas, the theory of Ukrainian victory has shifted in an unacknowledged but dramatic way. After years of insisting that it would achieve maximal territorial integrity - an outcome which would require the total and decisive defeat of Russia’s ground forces - Ukraine has reframed its path to victory mainly as a process of inflicting strategic costs on Russia that mount until the Kremlin agrees to a ceasefire. Consequentially, the debate about arming Ukraine has shifted from a conversation about armor and artillery - equipment useful for retaking lost territories - to a discussion about deep striking weapons like Tomahawks, which can be used to shoot at Russian oil refineries and energy infrastructure. In short, rather than move to prevent Russian from achieving immediate operational objectives in the Donbas, Ukraine and its sponsors are now seeking ways to make Russia pay a price such that victory on the ground is no longer worth it. It is unclear whether they have thought about what price Ukraine will pay in the exchange. Perhaps they do not care.

About TomahawksNotwithstanding Ukraine’s attempts to jumpstart indigenous production, it is inevitable that Ukrainian capabilities will be largely determined by the largesse of western sponsors. This aspect of the war took a sudden turn at the beginning of the October when fresh reporting began to circulate that Tomahawk missiles might be on the table for Ukraine. Tomahawks have always been on Ukraine’s wish list (given that the Ukrainian wish list as such consists of essentially all the military equipment in NATO’s combined inventories) but this was the first reporting that they might be under serious consideration.

As is frequently the case, the discussion spiraled away from realistic grounding, with some suggesting that t he Tomahawk would be a “game changer” for Ukraine (where have we heard that before?) and the pro-Russian sphere dismissing it as an irrelevant distraction. There’s a tendency to focus on the quality of American weapons systems, casting them as either unrivaled technological marvels or overhyped and overpriced baubles, but this is generally not productive and largely irrelevant to the matter at hand. The Tomahawk, broadly speaking, is exactly as advertised, and provides proven and reliable strike capability at strategic depths in excess of 1,000 miles. In role, range, and payload it is essentially an analog to Russia’s Kalibr missiles (I am begging the enthusiasts to note the phrase “essentially an analog” rather than rake me over the coals over the different guidance systems and other technical minutia). Such a system will always be valuable and would obviously improve Ukraine’s deep strike capabilities.

The “problem” with Tomahawks does not relate to any “problem” with the missile itself, but with its availability and Ukraine’s technical capability to launch them. The Tomahawk is conventionally a ship-launched missile (there is no extant air-launched variant) with a few novel options for ground launch. Ukraine, obviously, would require ground launch systems, and the problem is that these systems are essentially brand new and available in very limited quantities: more importantly, American service branches are in the process of trying to build out these capabilities throughout the decade. Providing ground-launchable Tomahawks to Ukraine in any meaningful numbers would therefore essentially require the US Army and Marines to scrap their own force buildout plans.

There are two basic options for ground launching Tomahawks. One of these is the US Army’s MRC (Mid-Range Capability) Launcher, dubbed the Typhon. This is an enormous tractor-trailer launcher with four launch tubes, first delivered in 2023. It has an enormous footprint - so large, apparently, that the Army is already asking for a smaller replacement - and is intended to give the Army an organic fires component in the gap between the shorter range Precision Strike Missile and hypersonic systems (which do not yet exist). The critical fact is this: the Army intends to field a total of five Typhon batteries by 2028, of which two have been delivered so far. Each battery consists in turn of four launchers, implying that eight out of a planned twenty launchers have been delivered. Even more importantly, both of the currently operational batteries are already deployed, with one in the Philippines and one in Japan. These systems are being actively used in exercises and trials, including an exercise this summer in Australia.

The Typhon system gives ground launch capability to the Tomahawk but brings a massive footprint

The situation with the Marine Corps’ launch system is quite similar, although the launch platforms themselves could not be more different. Unlike the lumbering Typhon tractor trailer, the Marines are fielding a significantly more lithe and compact LMSL system, with the tradeoff of a single launch tube compared to the Typhon’s four. What matters is not so much the technical differences, as the fact that the Marines - like the Army - only received their first deliveries in 2023, and they are currently in the process of building out the force. In the case of the marines, the goal is to have a Tomahawk battalion built out by 2030. In fact, the production contract came into effect as recently as 2025.

What does all of that mean? It means that, although the Tomahawk itself is a fine missile, the systems for ground launch are so new and available in such limited quantities that equipping Ukraine with Tomahawks would require either the US Army or the Marines to materially alter their force structure in the near term (through 2030, essentially). These are essentially the opposite of much of the gear that’s been given to Ukraine to this point: far from being inventories of older systems that can be earmarked as surplus or tabbed for replacement, Tomahawk ground launch is a brand new capability that is in the middle of deployment and buildout for the first time.

This is, of course, a layered complication on top of Tomahawk quantities in and of themselves. The issue of Tomahawk availability is both over and under emphasized, depending on the context. The United States has something like 4,000 Tomahawks in its inventories (although half of these are currently inside their cells on American ships), so it is not quite correct to say ( as some have) that America is running out of these critical weapons. The issue is that production rates are relatively anemic (generally between 55 and 90 per year) and are fail to replenish the expenditure from even relatively brief strike campaigns, such as the repeated strikes on Yemen. Broadly speaking, then, the issue is not so much that the United States is in immediate danger of running out of Tomahawks, but that procurement schedules are so slow that even relatively minor expenditures can erase multiple years worth of deliveries.

It may be useful, then, to consider Tomahawks in comparison to the ATACMs missiles which have already been provided to Ukraine. Unlike the Tomahawk, the ATACMs is a system which has already been tabbed for replacement, with the Precision Strike Missile in the early phases of its rollout. ATACMs were also compatible with launch systems that Ukraine already had. In comparison to Tomahawks, then, ATACMs are both vastly more strategically expendable, produced in larger numbers, and easier to deploy. Despite all these points in their favor, the United States provided Ukraine with just 40 ATACMs. Even if the Army could be pressured into handing over one or two of its brand new Typhon launchers, it is difficult to imagine that more than few dozen Tomahawks could be spared for Ukraine: a token inventory far too small to wage a sustained strike campaign in the Russian heartland.

Peace, Sponsored by Raytheon

Given that Tomahawks for Ukraine would be measured in the dozens, rather than the hundreds, it’s worth asking whether this could actually change anything for the AFU at the front. The answer is clearly no in the long run, but it would be unwise to dismiss the possibility that even a limited tranche of Tomahawks (let’s say 40 to 50 missiles) could help alleviate pressure on Ukrainian forces at the front, provided they were used appropriately. A short term boost to Ukrainian strike capabilities, if deployed against Russian rear areas, could force further dispersal and rationing of Russian assets and temporarily stall Russia’s emerging multi-axis offensive. This could defer the loss of key positions until early 2026. This presumes, however, that the Ukrainians would be content to use Tomahawks against operational targets. In reality, Ukraine can never seem to resist lobbing missiles at targets that have little bearing on the front, like the Kerch Bridge. Indeed, a failure to synergize strikes at depth with operations on the ground is a major reason why the ATACMs achieved so little.

On the other side of this equation, it is a common complaint from the Russian perspective that Moscow has done too little to “deter” the United States from empowering Ukraine’s strike campaign - both by directly providing munitions and supplying the planning, ISR, and guidance systems. This, however, rather misses the point. Russia has done nothing of note to deter the United States because both Moscow and Washington understand fully that there is essentially no appetite (on either side) for a direct confrontation. In the (sensible) absence of a willingness to strike back at NATO targets, there is really nothing Russia can do to deter beyond maintaining its own retaliatory capabilities. The issue is not that Russia has failed to actively deter, but that there is nothing they could do even if they wanted to.

The basic pattern here is well established. The United States has done what it can to backstop Ukrainian strike capabilities, but it has held them at a level where Ukraine’s damage output falls far short of decisive levels. So long as that is the case, Russia has clearly demonstrated that it will simply eat the punches and retaliate against *Ukraine*. Hence, when the United States helps Ukraine target Russian oil facilities, it is Ukraine that receives the reprisal, and it is Ukraine which has its natural gas production annihilated as the winter approaches. In a sense, neither side is really trying to deter the other at all. The United States has raised the cost of this war for Russia, but not enough to create any real pressure for Moscow to end the conflict; in response, Russia punishes Ukraine, which is something the United States does not really care about. The result is a sort of geostrategic Picture of Dorian Gray, where the United States vicariously inflicts cathartic damage on Russia, but Ukraine accrues all the soul damage.

In the case of Tomahawks, the risk-reward calculus is just not there. Tomahawks are a strategically invaluable asset that the United States cannot afford to hand out like candy. Even if the launch systems could be provided (highly doubtful), the missiles could not be made available in sufficient quantities to make a difference. The range of the missiles, however, significantly raises the probability of miscalculation or uncontrolled escalation. Ukraine shooting American missiles at energy infrastructure in Belgorod or Rostov is one thing; shooting them at the Kremlin is another thing entirely.

There is, however, another aspect of this which seems to be garnering little attention. The biggest risk of sending Tomahawks is not that the Ukrainians will blow up the Kremlin and start World War Three. The bigger risk is that the Tomahawks are used, and Russia simply moves on after eating the strikes. Tomahawks are arguably one of the last - if not *the* last - rung in the escalation ladder for the USA. We have rapidly run through the chain of systems that can be given to the AFU, and little remains except a few strike systems like the Tomahawk or the JASSM. Ukraine has generally received everything it has asked for. In the case of Tomahawks, however, the United States is running the most serious risk of all: what if the Russians simply shoot down some of the missiles and eat the rest of the strikes? It’s immaterial whether the Tomahawks damage Russian powerplants or oil refineries. If Tomahawks are delivered and consumed without seriously jarring Russian nerves, the last escalatory card will have been played. If Russia perceives that America has reached the limits of its ability to raise the costs of the war for Russia, it undercuts the entire premise of negotiations. More simply put, Tomahawks are most valuable as an asset to threaten with.

Reading between the lines of President Trump’s public statements recently, it seems likely that he has rationally weighed these considerations. Publicly, he used the threat of Tomahawks to try and force Russia to keep negotiating, and he’s received a commitment for another meeting with Putin for his trouble (more on that later). He has now, for the time being, shelved the Tomahawk plan, commenting that “we need them” and applying the usual Trumpian linguistic style to the broadly accepted issue of inventories which I have outlined here. Tomahawks are simply more valuable to the United States as a tool to threaten escalation, rather than as an actual kinetic asset in Ukrainian hands, and so long as Trump keeps his powder dry he can re-raise the issue later.

Ultimately, perhaps, this discussion is not about Tomahawks at all. These missiles, rather, are simply a totem which demonstrate two important dovetailing points. First, that American resources are not infinite, and as the United States reaches deeper into its bag to help Ukraine, it begins to grab at strategically critical assets that the US military simply cannot spare. Secondly, we must remember that America’s policy in Ukraine is a game of titration, with Washington probing the limits of Russia’s willingness to “eat the strikes” without allowing the reprisal violence to spill out of Ukraine.

The Big Banana: Russia’s Operational SchemaAt this point, it’s becoming increasingly difficult to say anything meaningful about the actual operational progression on the ground. There are several reasons for this. First and foremost, the war has now gone on so long and is consistently moving at such an apparently glacial pace that most people simply do not care at this point whether Russia holds Yampil or not, or whether they have advanced past the rail line in Pokrovsk. There is severe fatigue (or perhaps boredom is the better word) with the status of an interminable sequence of apparently small settlements, industrial complexes, and forestry plantations, and as a result most people have essentially checked out. Not the least among these must surely be President Trump, who apparently chucked Zelensky’s map of the frontline and complained that he was tired of being shown the same maps over and over again.

On the other hand, we have the true obsessives who continue to dutifully follow the frontlines regularly and are voluntarily intaking daily updates. We end up with a bifurcated system where some people are still highly plugged in to the micro movements on the battlefield, but most people just don’t care, and we can hardly blame the latter. I think it would be profitable, then, to think about the broader Russian operational scheme, what it has achieved, and what it aims to achieve in the coming year. This is probably more interesting and less repetitious than fixating on the exact positioning within Pokrovsk or Kupyansk.

There are two larger points that I think are worth making before we look at some specifics.

First and foremost, much of the battlefield analysis that comes out (particularly from western analysts) makes firm pronouncements as to what constitutes Russia’s “primary” and “secondary” efforts, but these are essentially interpolated and frequently incorrect. For example, it’s become a fairly mainstream conception that Russia’s “primary” point of effort right now is the capture of Pokrovsk, but this does not actually seem supported by Russian actions. There is no particular advantage to be gained for Russia by pushing to capture Pokrovsk as soon as possible - the city is already in a stranglehold partial encirclement. To be sure, Pokrovsk *was* a major logistic hub for Ukrainian forces, but it can no longer serve that role and was sterilized as a transit hub months ago, once it became a frontline city. The opposite side of this coin is that other Russian axes of advance, particularly in southern Donetsk and the bend of the Donets River, are dismissed as “secondary” efforts. This is a major mistake, and I will attempt to show that these are critical advances where Russia is shaping the battlefield to its advantage for follow on operations.

Secondly, it should be understood and appreciated that Ukraine has lost essentially all battlefield initiative. In 2024, the AFU was able to assembled a mechanized reserve and launch their operation into Kursk. This operation ultimately failed and resulted in severe Ukrainian losses, but this is unrelated to the fact that Ukraine was still able to accumulate forces and pursue offensive operations on its own initiative. In 2025, however, Ukraine has been in a permanent state of reactivity. This was the first year of the war in which Ukraine did not launch any proactive operations or counteroffensives of its own, and Ukrainian hopes have instead pivoted to their strategic strike campaign against Russian oil facilities.

In a larger sense, the effect of attrition can be seen year by year with the shrinking scope of Ukraine’s proactive operations. In 2022, Ukraine was able to launch a pair of widely separated offensives which yielded modest successes: an offensive out of Kharkov rolled the front back over the Oskil River (though it failed to collapse the Lugansk shoulder), meanwhile, a series of battles outside of Kherson failed to break through the Russian lines, but they did play a role in persuading the Russians to abandon their bridgehead over the Dnieper. The point of course is not to once again autopsy these offensives, but to point out that there were two of them, that they were meaningful in scale, and they did result in important territorial gains for Ukraine. In 2023, by contrast, Ukraine launched a single theater-level offensive in the south, which failed. In 2024, we got the Kursk operation: smaller and less lavishly equipped than 2023’s Zaoprizhia offensive, and aimed at a peripheral theater. This year, there were no proactive Ukrainian operations at all. There is a very clear pattern at play here, with Ukraine’s offensive punch progressively shrinking before disappearing entirely in 2025. This was a year of essentially uninterrupted Russian initiative.

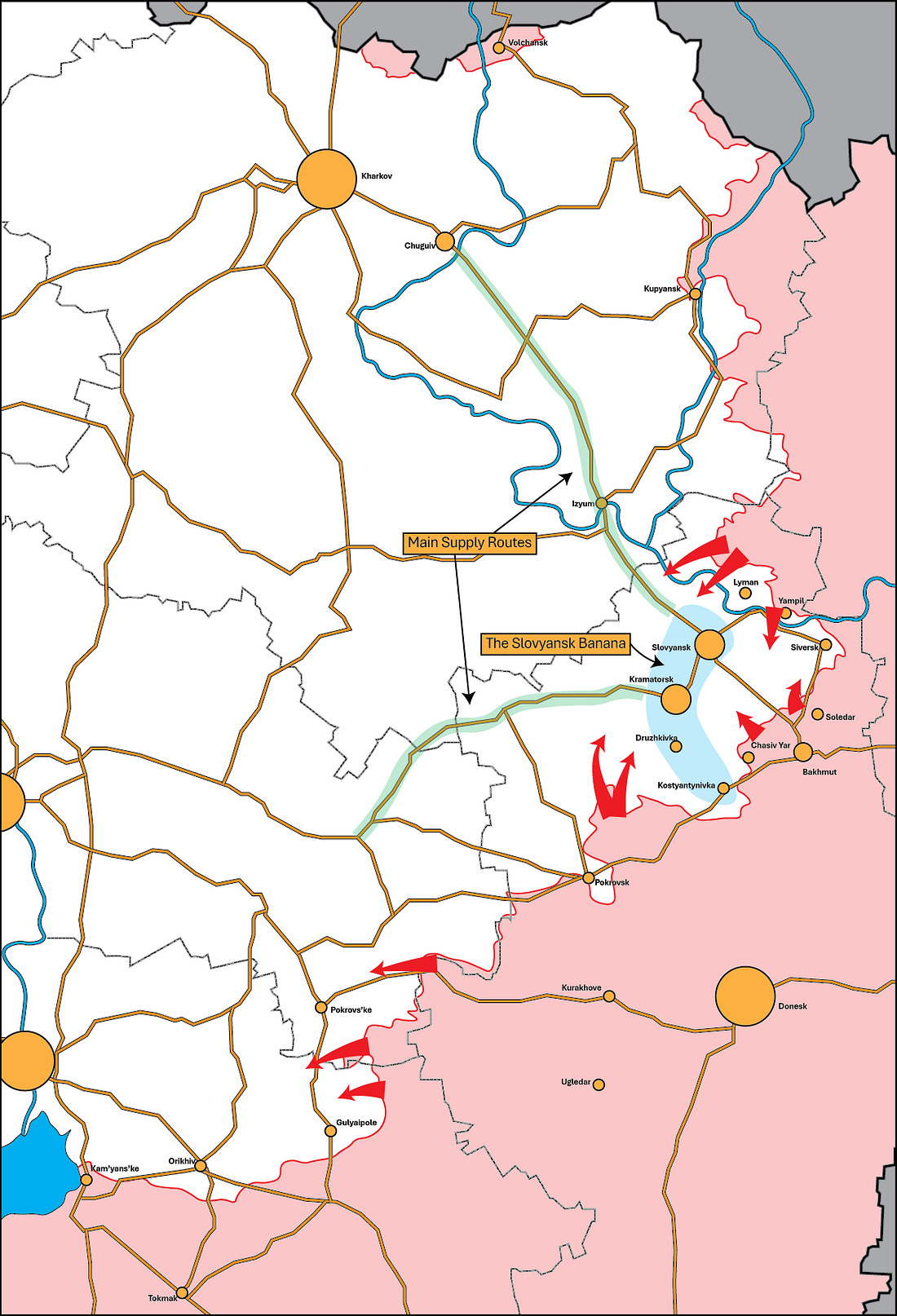

Putting Ukraine permanently on the backfoot is a significant Russian achievement, and it is owed to a few converging factors. Obviously, the attrition of Ukrainian forces is a major factor. We’ve gone through the flailing Ukrainian mobilization, the cannibalization of its forces, and the general lack of reserves in detail on several occasions, and there’s no need to retread that ground here. Suffice it to say, Ukraine’s ability to husband forces for offensive operations appears to be severely degraded. Russia has exacerbated this problem by pressing steadily on a variety of different axes. At the moment, there are no fewer than seven Russian axes of attack, pressuring a slew of cities all along the line. This creates a series of defensive emergencies, maintains the burn rate on Ukrainian forces, and fixes them on the line. Finally, in a point to be detailed shortly, Russian advances have begun unraveling Ukraine’s logistic connectivity, which puts strain on supply and prevents the concentration and accumulation of forces.

Eastern Ukraine: Approximate Situation and Axes of Russian Advance

Now, for the development of the front and the premise of the Russian offensive scheme. The main point that I want to impress is essentially as follows: rather than fixating on Pokrovsk, Russia’s advances across Southern Donetsk and on the inner bend of the Donets River ought to be thought of as vital operations which have severely disrupted the coherence of both the Ukrainian front and their logistics. This has the triple effect of preventing the Ukrainians from launching offensives of their own, accelerating the attrition of Ukrainian forces, and shaping the front for the coming operation to capture the Slovyansk-Kramatorsk agglomeration.

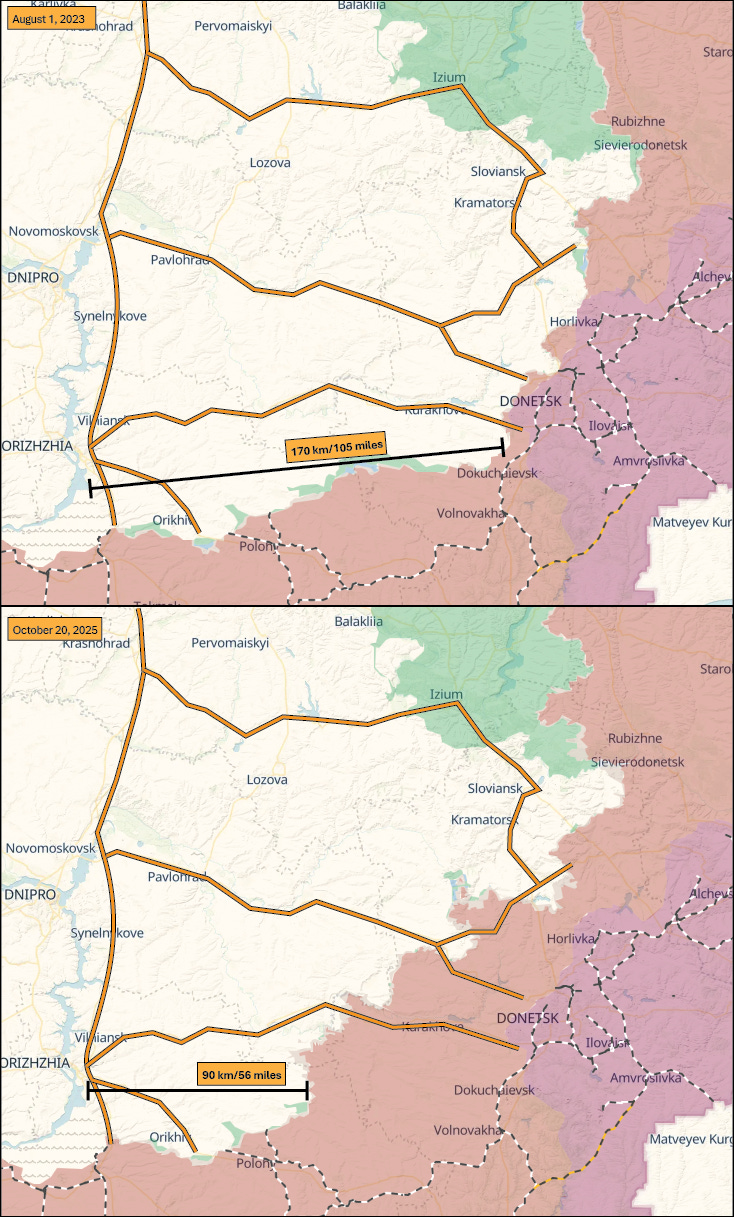

To begin, let’s consider the progress that Russia has made in southern Donetsk, both in raw territorial terms and its implications for Ukrainian logistic connectivity. To demonstrate this, I’ve pulled maps from DeepState (again, a Ukrainian mapping enterprise) for August 2023 (when Ukraine was attempting its counterattack out of Orikhiv) and for October 20th, the week of this writing. I have noted both the length of the southern front (obviously a linear approximate, as the actual front has many bends and bulges) and highlighted the key highways that Ukraine uses to run the backbone of its logistics.

The Southern Front: 2023 vs 2025

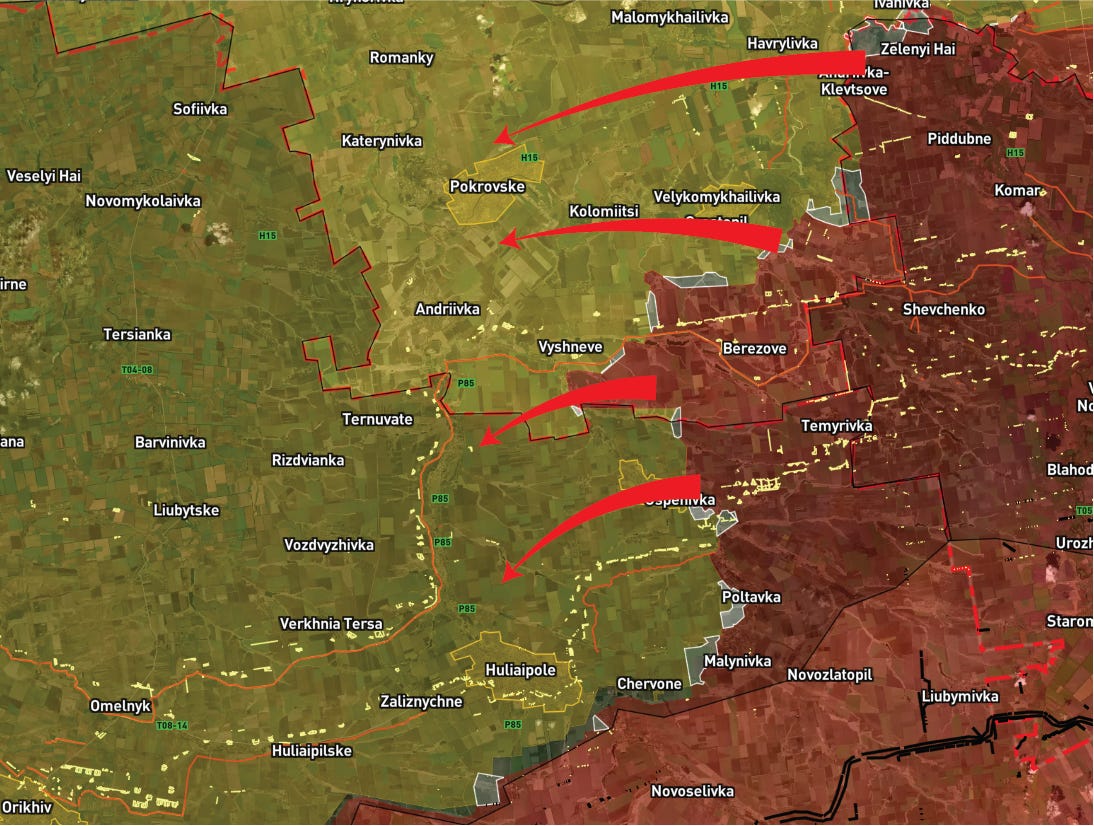

Now, one thing that is worth noting is that the Russians are currently positioned to roll up this front even further. Ukrainian defensive lines are primarily oriented towards on a north-south axis. Once Russian forces cleared Kurakhove, they entered the seams in these defensive lines - that is to say, they are advancing laterally along the face of the prepared defenses, rather than trying to bash through them from the front. This is one reason why their progress has been relatively steady and uninterrupted. Now approaching the “elbow” in the lines, where they pivot southward, and having crossed the Yanchur River, the Russians are entering a substantial space that lacks meaningful prepared defenses. Using the Military Summary map (Ukrainian fortifications are mapped with yellow dots), the void in the defense is fairly obvious as the Russians work their way into the elbow of the line.

Apart from the obvious development of note here - that Russian forces have, to this point, rolled up roughly half the length of the southern front and are positioned to roll up another ten to fifteen miles - we want to note two things which are emblematic of the way the war is going for Ukraine, but curiously receive little attention. First, the compression of the front is robbing the Ukrainians of the maneuver space which made it possible for them to stage and assemle forces for their counteroffensive in 2023. Two years ago, there was a wide, lateral buffer zone around the Ukrainian staging area in Orikhiv, and Ukrainian forces had access to multiple highways where they could disperse forces in their marching columns and run their logistics.

Today, that buffer zone is gone, as is the easy access to several of the branch highways. The Russian advance, which started with the breakthrough at Ugledar and Kurakhove last year and which has now rolled up some 50 miles of front, has essentially sterilized Ukraine’s capacity to attack in the south, because they have neither the space nor the roads to safely accumulate forces here. It has also shattered the interconnectivity of Ukrainian logistics: rather than having several highways to shuttle troops and material to the east, Ukraine now has to support several disconnected logistic fronts with individual highways. More to the point, there is no longer a single Donetsk “front” to speak of, but rather a series of logistic fronts: one in the south, around Orikhiv, another at Pokrovsk, and the largest one in the Slovyansk Banana. These are lacking lateral connectivity to each other for the Ukrainians due to the wedges that the Russians have forced in the front, particularly in the south, funneling logistics and reinforcements down individuated corridors.

The bigger issue, however, lies farther north on the Pokrovsk and Donets axes, and in the way that they synergize. People who are focusing, to the exclusion of all else, on when and how Russia will capture Pokrovsk are failing to see the bigger picture, and indeed are not even trying to understand it.

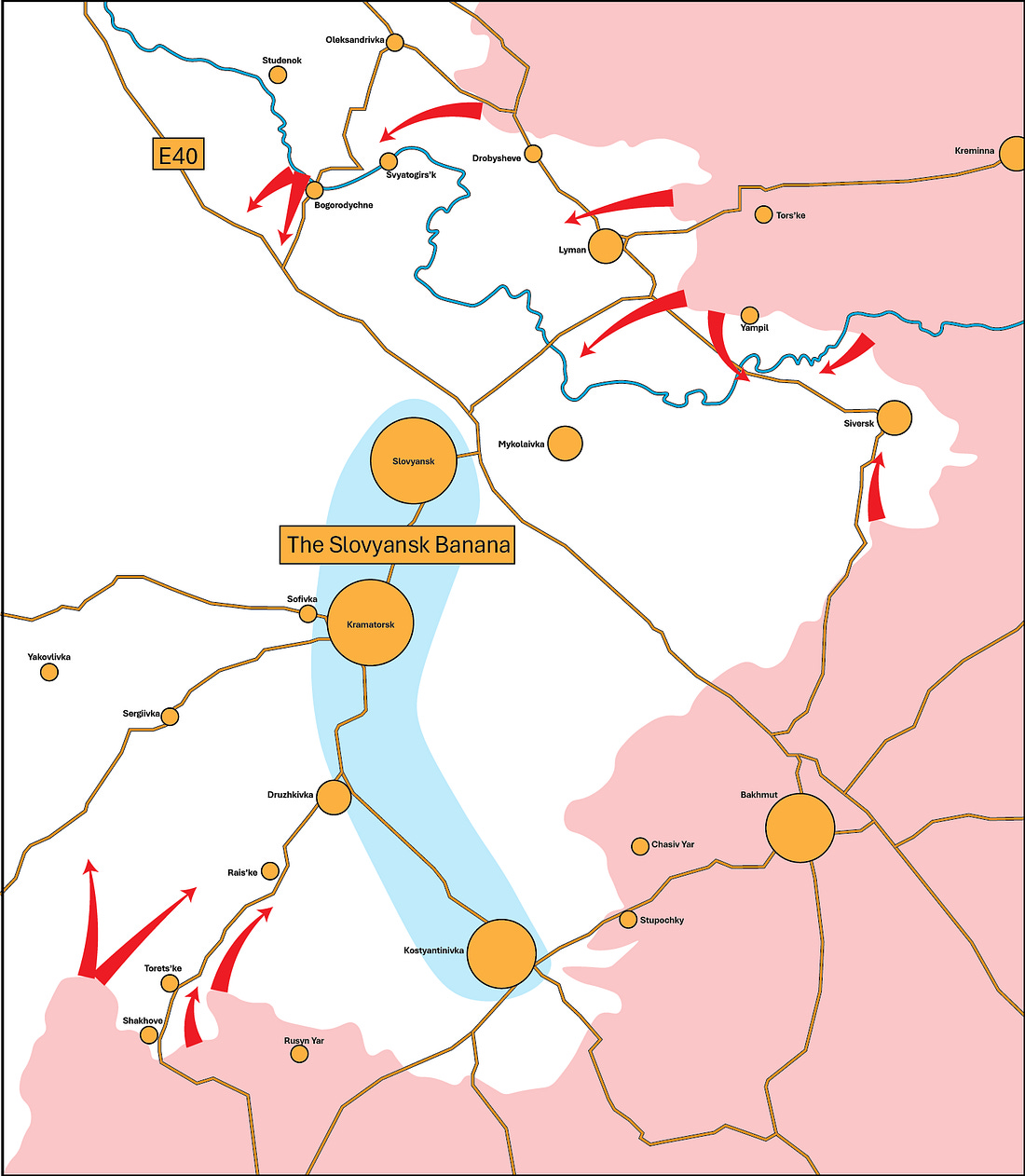

The ultimate Russian operational objective (in this phase of the war, at least) is the belt of cities which runs in an arc from Slovyansk to Kostyantinivka, which I affectionately call “the Slovyansk Banana” due to its curved shape. A cursory look at the map shows us why the very operations that are being dismissed as secondary efforts are in fact critical axes of Russian effort which are shaping the battlefield for the attack on the Banana.

There are two very important facts about the Banana, from the perspective of operational geography. The first is that, although the combined mass of the agglomeration is far larger than any of the urban areas that have been fought over to this point, the Banana is relatively difficult to defend because it sits on the floor of a river valley: the Kazennyi Torets flows through all the cities in the Banana before it flows into the Donets. Russian forces approaching the city from the southwest, the east, and the north will all be advancing along the high ground that overlooks the cities on the floor.

The second important fact about the Banana is that, despite its size, it is supported by just two highways which approach from the southwest and northwest respectively, funneling into the Banana like a wedge. Taking the northern highway/MSR (the E40 highway) as an example, we see that Russia’s operations inside the Donets bend are hardly secondary efforts: they are vital shaping operations linked to the integrity of the Banana. The E40 highway tracks the Donets bend very closely (it generally stays within five miles of the river. If the Russians sustain their progress north of the Donets and reach the river at Bogorodychne or Svyatogirsk, it will not only put E40 under persistent drone attack but also curl the defensive line behind the Banana, to say nothing of the enormous pressure on the Siversk salient.

On the Pokrovsk front as well, Russia’s progress is being misinterpreted. After their breakthrough at the end of the summer, Russian forces have consolidated the bulge north of Pokrovsk (despite weeks of Ukrainian counterattacks) and are steadily working their way towards Rais’ke and Sergiivka. This is not about Pokrovsk at all - reaching Rais’ke would put Russian forces directly in the backfield of Kostyantinivka, on the supply lines to the underside of the Banana.

I am not suggesting at all that Russian forces are on the verge of some great offensive surge that will carry them into the heart of the Banana instantly. However, there is a fairly well established Russian operational methodology in this war, which involves working their way methodically into Ukraine’s logistical lanes and seams, segmenting the front and strangulating their strongpoints, forcing them to supply frontline strongholds with single file logistics and dirt roads. They did it in Bakhmut, and Avdiivka, they are doing it in Pokrovsk, and they are shaping the front to attempt this on a large scale in the Banana.

Assault on the Banana: Coming 2026

The general point that we are trying to make here is that dismissing Russian advances in the Serebryanka Forest, the emerging bulge north of Pokrovsk, and their move into the Donets Bend as “secondary efforts” is mistaken. Zooming out to the appropriate scale shows that these are concentric operations, shaping the front for a 2026 assault on the Banana - moving towards the E40 road from the north, bending the defensive shield around Siversk, and working into the underbelly of the Banana through Rais’ke.

This is, perhaps, a long way to go for a short drink of water, but there are a few basic points here that get completely missed when the view of the front is preoccupied with the fighting inside Pokrovsk and Kupyansk:

- Russia’s advance out of Kurakhove across the southern front is not a secondary axis. They have rolled up half of the southern front, condensing Ukrainian forces into a compact space which sterilizes their ability to attack in the south.

- Broad Russian pressure across a half-dozen axes maintained a steady burn rate on Ukrainian forces and prevented the accumulation of forces for proactive operations. 2025 has been the first year of the war in which Ukraine has not launched any offensive operations on its own initiative.

- Advances in the Donets bend and the interstitial space between Pokrovsk and Kostyantinivka are not subsidiary or secondary operations: they are critical shaping operations that are moving concentrically toward the Banana.

To be frank, the general mood of optimism in the Ukrainian infosphere, which lasted for much of the summer, struck me as remarkably odd. The frontline has yielded no real good news for Ukraine at any point this year. Beyond the broader strategic point, that Ukraine has lost the initiative and does not seem capable of getting it back, Russia is in the process of capturing two important urban centers (Russian troops are in the city centers of Pokrovsk and Kupyansk), it has begun the assault on at leas two more (Lyman and Kostyantinivka), it has rolled up half of the southern front, and cleared most of the inner Donets-Oskil bend. The Banana is on deck for 2026.

Ukraine’s Cost Theory of Victory One thing that has become apparent over the last year is that Kiev has abandoned previous notions of outright victory on the battlefield and adopted a new strategic framework predicated on imposing unacceptable costs on Russia, so that Moscow will agree to freeze the conflict.

This is a subtle and unspoken yet extremely important distinction. It is easy to miss, because both Ukrainian leadership and Ukraine’s western backers continue to speak of Ukrainian “victory” and the possibility of Ukraine “winning” the war. What is crucial to understand is that the “victory” that they speak of now is categorically different than the victory of 2022 and 2023. In the first years of the war, it was possible to at least speak of Ukraine taking the initiative to advance on the ground and retake territory. There were concrete examples of Ukrainian offensives in 2022, and the battle in Zaporizhia - although unsuccessful - showed that it was at least possible for Ukraine to attempt a proper mechanized offensive.

Therefore, in the first years of the war, when leaders in Kiev and Brussels and London and Washington spoke of Ukrainian victory, they essentially meant the defeat of the Russian ground forces and the reconquest of much (or all) of the Donbas. The Kursk Operation of 2024 began to split the difference: Ukraine still had some resources to mount proactive operations, but these operations were no longer aimed at the dense eastern front and instead aimed at relatively soft subsidiary fronts with an eye to out-levering the Russians.

Today, with the Ukrainian army stuck in a permanent state of reactivity and slowly receding defense, it no longer makes any sense to speak of Ukrainian victory in the most straightforward sense, which is to say victory on the battlefield - no matter how tenaciously or bravely the Ukrainian rank and file continues to fight in essentially intolerable circumstances. Instead, Ukrainian “victory” has been transmogrified to mean essentially that Russia absorbs such exorbitant costs that it agrees to some sort of ceasefire without preconditions.

The costs to be imposed on Russia are implicitly assumed to be a mixture of battlefield casualties and damage to strategic assets inflicted by Ukrainian air strikes, and in regards to the latter Ukraine seems to be particularly placing its hopes in a strategic strike campaign against Russian oil. Ukraine’s attempts to disable Russian oil production and refining have dovetailed with ever more aggressive sanctions from the United States against Russian fossil fuel exports - although it is worth noting that the limited price response to these sanctions indicates that markets expect that Russian oil will continue to flow.

Trump’s suggestion that Tomahawks may be on the table for Ukraine must be seen as a constituent element of this new strategy and theory of victory. And this, ultimately, is very important to understand. Tomahawks are not being bandied about because anybody (in Kiev or Washington) believes that 50 cruise missiles will allow Ukraine to defeat the Russian Army and recapture the Donbas. Tomahawks were mentioned because the Ukrainian alliance is threatening to cripple the Russian fossil fuels industry (through a mixture of sanctions and kinetic strikes on production facilities) unless Putin agrees to a ceasefire.

This is why it is wrong to be surprised that Trump abruptly cancelled his meeting with Putin and instead announced more sanctions. There’s nothing abrupt or erratic about this. Threats to Russian oil are now, without exaggeration, the main lever that the Ukrainian bloc has against Russia. It certainly should not have been a surprise that the Kremlin, which has reiterated the same fundamental war aims since day one, was not excited about coming to Budapest to freeze the conflict, and neither should it surprise us that Trump would instead prefer to pull harder on the oil lever. The two powers are playing entirely different games: Russia is slow-walking negotiations while it advances on the ground, and the United States is playing a pain game designed to raise the costs for Russia.

We have fundamentally reached an impasse when it comes to negotiations. For Moscow, negotiations with the United States are essentially a way to string Washington along. Moscow feels that it is winning on the ground, therefore a diplomatic impasse suits Russian interests. When western leadership complains that Russia does not seem interested in ending the war, they are correct, but they are missing the point. Russia is not interested in ending the war right now because doing so would not serve Russian interests. The Banana is in the crosshairs, and a ceasefire now would be an egregious compromise when victory on the ground is in sight.

The sense of urgency that Washington feels to end the war - mainly by yanking furiously on the oil lever until the Kremlin cries uncle - stems from the fact that this is now the only sort of victory that Ukraine can hope to win. The ground war has been written off as a total loss, and all that remains is to lob missiles and drones at Russian refineries, sanction Russian firms and banks, and harass shadow tankers until the costs become intolerable. The longer the Ukrainian ground forces can hold the line the better, but this is merely a matter of limiting the downside. The fact that Russia can retaliate disproportionately against Ukraine barely factors into this thinking.

The key point here, however, is that the concept of Ukrainian victory has been completely transformed. There is now no real discussion of how Ukraine can win on the ground. For the Ukrainian bloc, the war is no longer a contest against the Russian Army, but a more abstract contest against Russia’s willingness to incur strategic costs. Rather than preventing Russian capture of the Donbas, the west is testing how much Putin is willing to pay for it. If history is any guide, a game predicated on outlasting Russia’s strategic endurance and willingness to fight is a very bad game to play indeed. |