Here's just how big a victory Prop 50's passage is for Newsom

Story by Sophia Bollag

• 4h

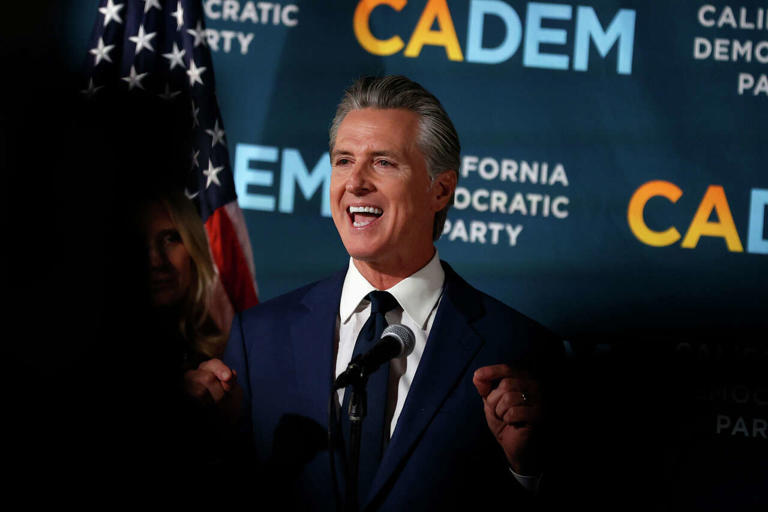

California Gov. Gavin Newsom prepares to speak at the California Democratic Party headquarters after polls close in the statewide special election on Proposition 50, a redistricting ballot measure, in Sacramento on Nov. 4, 2025. (Stephen Lam/S.F. Chronicle)

SACRAMENTO - Gov. Gavin Newsom raised so much money for his campaign to redraw California's congressional districts that last Monday, more than a week before Election Day, he did something almost unheard of. He told his supporters to stop donating.

"We have hit our budget goals and raised what we need in order to pass Proposition 50," he wrote in an email to supporters. "You can stop donating."

The remarkable evolution of Prop 50 - which went from a vague, half-baked idea to a resounding victory in less than four months - is certainly due in part to Californians' attitudes about President Donald Trump, who has aggressively targeted the state since taking office in January. But it also represents a significant victory for Newsom as he sets his sights on life after the governor's office - a moment that happens to coincide with Democrats' ongoing struggle to find a leader and a vision to counter Trump.

Newsom first began to talk about the issue in mid-July after news broke that Trump was pressuring Texas Republicans to draw new maps to favor their party in the 2026 congressional elections. The practice of gerrymandering, or drawing political districts to favor specific political parties or politicians, is already standard across the country. But Texas' decision to redraw its maps in the middle of a decade - not tied to a census - and the president's role in the situation was not.

Newsom responded with a vague but ominous threat.

"Texas is using a special session about emergency disaster aid to redistrict their state and cheat their way into more Congressional seats," he wrote on social media. "CA is watching - and you can bet we won't stand idly by."

At first, his comments drew some skepticism from political observers, who questioned whether California voters would go along with the plan. Californians voted in 2008 and 2010 to establish a nonpartisan commission to draw the state's congressional districts. To replace the maps drawn by the commission, Newsom needed to go back to voters.

When Newsom first began making the threats, he and his team hadn't decided to do that, said Juan Rodriguez, one of Newsom's lead political consultants. They were still assessing polling on the issue, which initially did not look great. One early poll showed support was around 38%, Rodriguez said.

To get the issue on the ballot, Newsom had to convince two-thirds of California lawmakers to vote for it. In late July, when the Chronicle contacted all 37 Democrats who represent the Bay Area in the state Legislature, just two said explicitly that they supported the governor's plan. Most declined to comment or did not respond.

Sen. Dave Cortese, D-San Jose, said at the time he supported the governor's overall plan, but that calling a special election in November would be an unrealistic timeline.

"I never use the word impossible, but that's about as close as you can get to impossible," said Cortese, who serves as the Senate majority whip. Three weeks later, he voted alongside his colleagues to put the issue on the ballot on Nov. 4.

Two prominent groups that criticized Newsom's initial plan, California Common Cause and the League of Women Voters of California, took back their opposition to the measure within weeks. Redistricting commissioner Sara Sadhwani told the Chronicle in mid-July she didn't think Newsom could pull off mid-decade redistricting. A couple of weeks later, she changed her tune and soon became one of the top spokespeople for the campaign, even starring in one of the campaign's ads.

"I couldn't envision it," Sadhwani told the Chronicle in a follow-up interview in September. "Redistricting tends to be such an esoteric, wonky part of the democratic process that I didn't realize that he would move forward with a special election."

Mark DiCamillo, the lead pollster for the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley, said voters showed "extraordinarily high" awareness about the ballot measure a week before the election. Usually measures with such high awareness levels are ones that affect people's day-to-day lives, like Prop 13 in 1978, which impacted property tax rates.

Early public polling on Prop 50 showed high rates of undecided voters and support from just over 50% of respondents. That's often a bad sign for a ballot measure because support tends to erode over time.

Normally, a well-funded opposition campaign has an advantage in a ballot measure fight because they can erode support simply by raising doubts in voters' minds about a measure, said DiCamillo. But the high level of partisanship in this race made it an exception, with Democrats generally supporting it and Republicans opposing. A week before Election Day, poll numbers in support of the measure had soared.

Newsom's role as the face of the campaign could have played into the opponents' argument that the measure was simply a power grab by Sacramento Democrats. But his involvement seemed to boost the measure. More than half of voters who supported Prop 50 in UC Berkeley's recent poll said Newsom's support for the measure helped convince them to vote for it.

Newsom also tapped his massive nationwide network of donors he began building during the recall election in 2021, when conservative groups unsuccessfully tried to remove him from office.

In hindsight, that recall election "absolutely" helped Newsom in the long run by giving him a platform to build a nationwide base of support, Rodriguez said. That network came through on Prop 50, giving more than 1 million individual small-dollar donations in support of the measure. The campaign outraised opponents' more than 2-to-1, and helped Newsom expand his fundraising network further.

Newsom started Trump's second term trying to work with the president after devastating wildfires leveled whole neighborhoods in Los Angeles. But their relationship soured quickly and Newsom became one of the president's chief antagonists. After Trump deployed National Guard troops to the streets of Los Angeles, especially, Newsom adopted a much more aggressive tone toward the president. He gave a primetime address accusing Trump of assaulting democracy. Launched a social media onslaught against the president and other Republican officials. Traveled to parts of South Carolina, which he billed as an effort to challenge the GOP on its home turf.

With Prop 50, Newsom was able to turn that rhetoric into action.

"(Trump) did not expect that we would go to the ballot," Newsom told reporters last week. "I think the best he expected is I would submit an op-ed and pray that maybe one of the major newspapers will pick it up. They didn't expect this."

In recent weeks, Newsom has also changed his tune on one of the questions he's asked most frequently: whether he plans to run for president.

After years of insisting he has "sub-zero interest" in the White House, he earlier this year conceded that he's thinking about it. Last week, he said he would make a decision on a 2028 White House run after the midterm elections next year.

The victory of Prop 50 will help boost those prospects, said Mike Madrid, a California-based Republican consultant. Whether the momentum he's built can be sustained much beyond this week is unclear, Madrid said, but the campaign has helped the lame-duck governor launch himself to the top of the national conversation.

"It cements a process he already began to establish himself as the national leader of the Democratic Party," Madrid said. "Just by fighting, he's given the Democrats hope." |