Affordability, Part III

What should a serious policy agenda include?

Paul Krugman

Dec 14, 2025

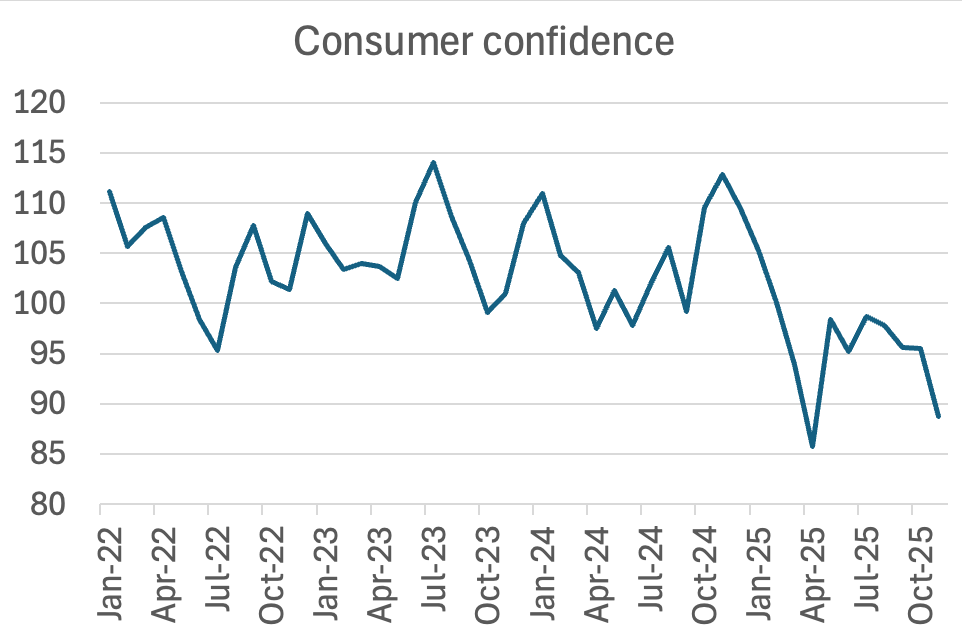

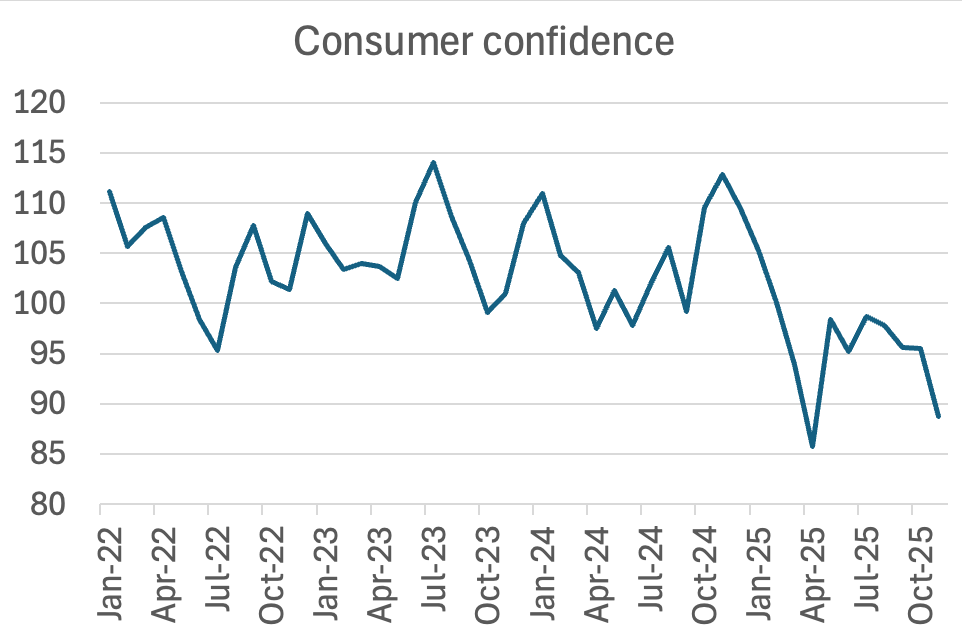

Source: Conference Board via Haver Analytics

Americans are in a deep funk over the state of the economy. The chart above shows consumer confidence as estimated by The Conference Board from January 2022 to the end of October 2025. Early 2022 marked the beginning of the worst period of post-Covid inflation. Since then inflation has fallen dramatically -- from 9 percent in June 2022 to 3 percent now. But consumer sentiment fell sharply in late 2024, rose a bit during the summer, and is now falling sharply again. If one word can summarize Americans’ economic anxiety, it is “affordability.”

This is the third primer in a series on affordability. It was intended to be the last, but as I’ve discovered, there is so much to the topic that there will be a fourth installment next week. Much of the public’s concern about affordability stems from the simple fact that prices are considerably higher than they were 5 years ago. But that simple view obscures some important and subtle factors. In the first installment I discussed reasons why Americans are anxious about affordability even though conventional economic measures (such as real wages) indicate that most Americans’ purchasing power is higher now than it was before the pandemic. I also covered why conventional economic measures of purchasing power are probably deficient in capturing people’s economic reality.

In the second installment I argued that perceptions of affordability are shaped by considerations that go beyond purchasing power: economic inclusion, economic security, and perceptions of fairness.

In this third installment I will sketch out elements of a policy agenda to address Americans’ affordability concerns. Realistically, this can only be a Democratic agenda because Donald Trump and the MAGA Republicans refuse to acknowledge that there is a problem. In his Tuesday speech, the kick-off event of his “Affordability Tour”, Trump declared that affordability is a “hoax” and that “prices are coming down very substantially.” On Thursday Republicans in Congress flatly rejected a proposal to extend federal subsidies for health insurance, which would have averted a severe shock to affordability that will hit tens of millions of Americans at the end of this month. And anyone who protests this denial, like Marjorie Taylor Greene, quickly finds a target on their backs. In lockstep with Trump, the G.O.P. is in denial over Americans’ affordability concerns.

So this raises the question: What can and should Democrats promise to do to address affordability?

Beyond the paywall I’ll address the following:

1. What policy can’t do: During the 2024 campaign Trump promised to bring the overall level of prices way down; now he’s falsely claiming that he is in fact doing so. In reality, overall prices can’t be reduced substantially, and it would be a big mistake to try.

2. Undoing Trump’s damage: Policy can’t achieve a large decline in overall prices. It can, however, limit and in some cases reduce individual prices. To an important extent this can be achieved simply by reversing destructive Trump policies.

3. Beyond Trump: Much of an effective affordability agenda can consist simply of ending Trump’s destructive policies. But there’s still a lot more that can and should be done.

This will be a sketch, not a detailed policy manifesto. The broad message is that we should accept the things we can’t change — prices are not going back to 2019 levels — but try to change the many things we can in ways that are positive for the American people.

And in the fourth and final entry in this series I’ll get into issues that go beyond prices and real wages: Social inclusion, economic security and fairness.

Caution: Overall prices won’t and shouldn’t come down

Before I dive into policy proposals, caution is warranted against promising too much. One important reason that Americans are so pessimistic about the economy is that they were lied to: during the 2024 campaign Trump made extravagant promises to bring prices way down, and has utterly failed to deliver (except, apparently, in his own mind.) Democrats definitely should not make the same mistake. The fact is that the overall cost of living is not going to return to the level of a few years ago. In fact, it’s very unlikely that any sane policy will lower the price level at all.

Why do I say this? Experience. In modern economies the overall price level almost never falls except in the face of depression.

With the unique and complicated exception of Japan, modern economies almost never experience deflation — overall falling prices. We may sometimes see price declines for commodities like eggs and falling prices for goods like computer equipment experiencing rapid technological progress. But the broad basket of consumer goods considered in the Consumer Price Index and similar measures doesn’t fall unless the economy is deeply depressed, and even then doesn’t fall by much.

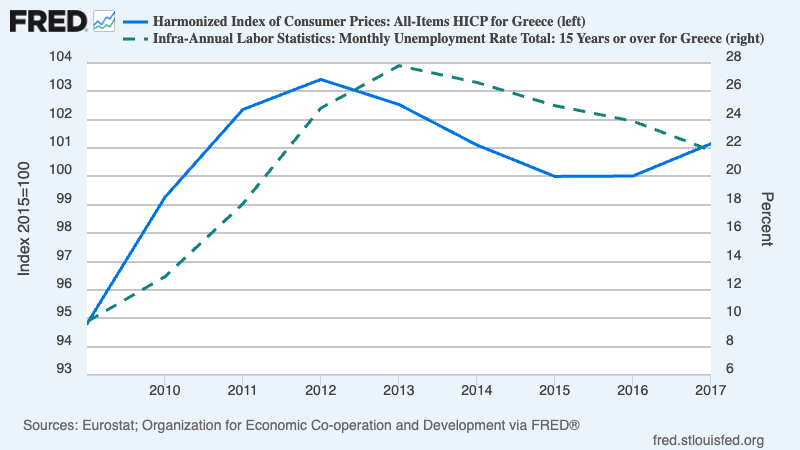

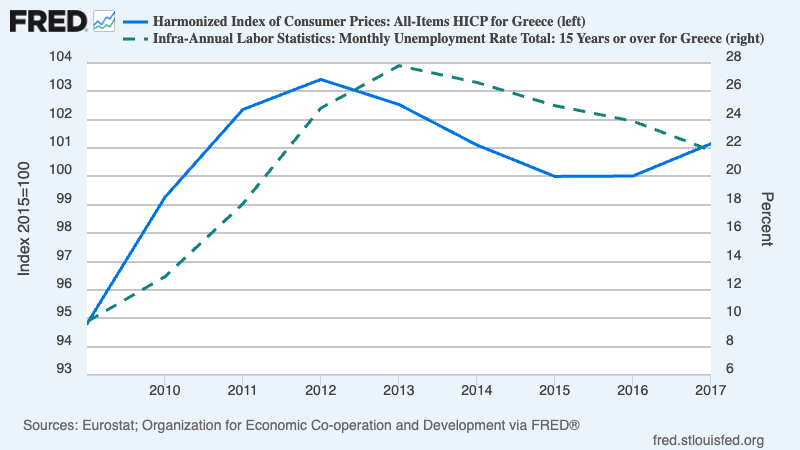

To see what I mean, consider the example of Greece, which experienced a Great Depression-level slump in the early 2010s. Unemployment rose to 28 percent, and prices did fall a bit — but only by a few percent:

In the U.S., the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the worst slump since the Great Depression, led to slower inflation — prices rising more slowly than before. But it didn’t cause deflation.

Why don’t overall prices fall? A significant share of prices is accounted for by wages, so prices can’t fall significantly without falling wages. And employers are unwilling to impose wage cuts because they know that this would have disastrous effects on worker morale and productivity.

So would-be policymakers shouldn’t promise to bring the overall level of prices down. They won’t be able to deliver and will face a political backlash.

Policymakers can, however, bring down some selected prices. In some though not all cases, this will involve reversing policies that have pushed prices up.

Undoing Trump’s damage

A good starting point for an affordability agenda will be to reverse policies that have driven prices up. Many though not all of these policies are recent initiatives of the Trump administration. So let me run quickly through a series of ways that reversing Trump’s actions can make prices lower than they would be otherwise.

Reverse the Trump tariffs: This is the obvious starting point. Since taking office, Trump has drastically increased U.S. tariffs, to levels not seen since the 1930s. Contrary to Trump’s assertions, foreigners are paying almost none of the cost of these tariffs. So far, U.S. businesses, reluctant to raise consumer prices, have absorbed much of the tariffs’ impact. Even so, the HBS Pricing Lab, using proprietary data, estimates that the Consumer Price Index is 0.6 percent higher than it would have been without the tariffs. The Yale Budget Lab estimates that the effect once the tariffs are fully passed through will be about twice as large: 1.2%.

So just reversing the Trump tariffs, almost none of which serve any valid economic or national security purpose, could shave more than 1 percent off the cost of living — around $1000 a year for the typical family.

Restore healthcare subsidies: Republicans have refused to extend enhanced subsidies for health insurance purchased through the Affordable Care Act. These enhanced subsidies were introduced in 2021 and expire at the end of this month. Their expiration will hit the 24 million Americans covered by the ACA with a double whammy. First, the government will cover a smaller share of their premiums. Second, rising premiums will cause some healthy people to drop coverage, worsening the risk pool. Anticipating this effect, insurers have already jacked up premiums.

KFF estimates that these combined effects will cause the average premium paid by ACA-covered families to rise by more than $1000 in 2026. The size of the hit will vary greatly but will be extreme in some cases. For example, a 60-year-old couple with an income of $85,000 will find itself paying more than $22,000 — more than a quarter of their pretax income — in extra premiums.

This major hit to affordability can be eliminated simply by restoring the subsidies.

End extreme anti-immigrant policies: At the start of Trump’s second term, officials declared their intention to prioritize the deportation of illegal immigrant criminals. What they have done instead is carry out mass dragnets that overwhelmingly sweep up immigrants without criminal records, some of them legally here. The administration has also moved to cut off legal immigration.

Putting numbers to the economic effect of these policies is difficult, in part because nobody really knows what the policies are, and I’ve seen a wide range of estimates. What we do know, however, is that immigrant workers are concentrated in a limited number of occupations, especially positions in agriculture, food processing, health care, hospitality and construction.

This concentration of immigrant workers has two important economic implications. First, for the most part immigrants don’t compete for jobs with native-born workers; they take the jobs native-born workers won’t. So deportations will do little to raise native-born wages.

Second, because immigrants play such a large role in production of some goods and services, mass deportations will reduce their supply and drive up their prices.

What about the argument that immigrants are driving up housing costs? This argument is adulterated nonsense — not unadulterated nonsense, because immigrants do have some effect on housing demand. But the best available estimates say that this effect is quite small. And any demand-side effect of mass deportations on housing affordability is swamped by the adverse effects on housing supply.

End the war on renewable energy: Soaring electricity prices have become a political flashpoint. There are several factors behind this rise, including a rise in natural gas prices after Russia invaded Ukraine and Europe began importing large quantities of LNG from the United States. One factor, however, has been the explosive growth in electricity demand from the data centers that power AI.

How much AI-related demand for electricity will grow in the future is uncertain. But there’s every reason to believe that overall electricity demand will surge in the years ahead. As the think tank Ember puts it, the world is in the early stages of an “electrotech revolution,” in which electricity-driven technologies, from electric vehicles to heat pumps — powered by renewable energy, which has experienced incredible technological progress in the past two decades — take over much of the economy.In China, which is expanding its global economic dominance, this revolution is already in full swing.

It’s foolish and self-destructive to imagine that the United States can cut itself off from this global revolution and hold on to an economy dominated by fossil fuels. Yet that has been the Trump administration’s vision. Not only have Trump and Co. ended U.S. industrial policy aimed at accelerating the energy transition, they’ve been doing all they can to block renewable energy development even when it’s profitable without subsidies.

Ending this attempt to move backwards and allowing America to rejoin the future will have many benefits, but one of them will be to help hold down the price of what will otherwise be unnecessarily expensive electricity.

This isn’t a comprehensive list of Trump policies we should reverse to improve affordability, but I hope gives a sense of what we can accomplish simply by not continuing to do self-harm.

Moving beyond Trump

According to the latest AP-NORC poll, only 31 percent of Americans approve of Donald Trump’s handling of the economy, while 67 percent disapprove. Given these numbers, Democrats may well be able to win the House, the Presidency, and possibly even the Senate simply by running against everything Trump has done.

But affordability as an issue didn’t start with Trump, and while undoing his damage will help, it won’t make the issue go away. So what can and should Democrats be proposing, beyond reversing Trumpism, to move forward on affordability?

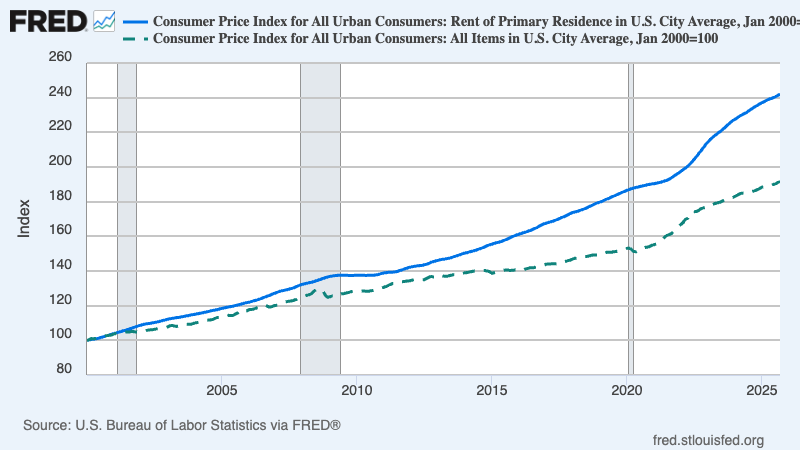

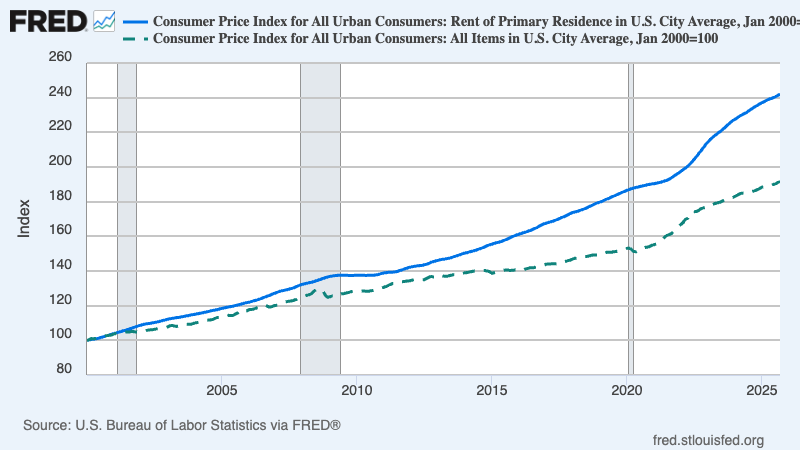

Housing: Over the past 25 years the cost of shelter has risen substantially faster than overall consumer prices. This chart shows the growth in average rent (solid line) compared with the Consumer Price Index (dashed line) since 2000:

Why look at rent when roughly two-thirds of Americans own their own houses? The Consumer Price Index measures the price of owner-occupied housing by “owners’ equivalent rent” — an estimate of what owners would pay if they were renters. The Bureau of Labor Statistics chose to use this measure for good reasons, but right now I have doubts about whether it adequately captures the affordability and social inclusion issues surrounding homebuying — a discussion that I want to reserve for the next primer in this series. So for now I’ll just focus on simple rents, which don’t have these conceptual issues.

And the rising cost of shelter has become a major source of concerns about affordability. What can be done about it?

The answer is simple: Build more housing. We know how to do this: Remove many of the restrictions and regulations that have limited housing construction. As I noted in the last primer, this is now an issue for both blue and red states. States like California and New York suffer from rules that make it very difficult to build housing of any kind. This is less true in places like Atlanta, which used to build a lot of housing — but this was overwhelmingly single-family housing at the metro areas’ edges, and red-state metropolitan areas are reaching the limits of sprawl. So they need to build more multistory, multifamily housing, which is severely restricted.

While upzoning can do a lot to hold down the cost of shelter, it’s also important to address construction costs. And this is an area in which we can do a lot simply by reversing Trump policies. End high tariffs on construction materials, such as lumber. Stop persecuting the foreign-born workers who play such a large role in the construction industry.

Beyond reversing Trump’s mistakes, policy should encourage low-cost construction. In particular, there’s still a social stigma associated with manufactured housing, but its quality is far higher than in the past and it costs much less to build than conventional housing — 35 to 73 percent as much, according to the National League of Cities. The Biden administration, in its last year, took some steps to encourage wider adoption of manufactured houses. We need more of that.

Childcare: Stay-at-home motherhood still exists in America, but it’s very much a minority lifestyle. According to the BLS, 74 percent of mothers with children — and 68 percent of mothers with children under 6 — participate in the paid labor force. Given the reality of modern society, childcare has become essential for American families.

Yet unregulated, unsubsidized markets do a very bad job of providing childcare. Why is a complex question. Suffice it to say that there’s a compelling case for government intervention to make childcare affordable and reliable, a case that even many pro-business groups accept.

And providing near-universal, highly subsidized or free childcare is eminently doable. Almost all advanced European countries do it. And here at home the state of New Mexico introduced universal free childcare starting Nov. 1.

Education: Once upon a time, America led the world in providing affordable public education. We still have universal free education through high school, although the quality is uneven. But in the modern world that’s often not enough — and our once-impressive system of affordable public higher education is now out of many families’ reach.

We don’t have to deliver free education at all levels. But making community college free and expanding access to trade education and apprenticeships could make a big difference to perceived opportunity.

Antitrust: America used to have strong antitrust policies, aimed at preventing monopolists and oligopolists from abusing their market power at consumers’ expense. Antitrust enforcement has, however, been steadily eviscerated since the Reagan years. And going back to taking market power seriously could have a visible effect on consumer prices.

This is a huge subject, probably appropriate for a future primer, and I won’t try to do more than raise it. But antitrust should be a part of an affordability agenda.

Consumer protection: We live, wrote Time magazine last year, in a golden age of scams. For a variety of reasons, financial fraud, especially aimed at middle- and lower-income Americans, has never been as widespread.

Policy can do a lot to protect consumers against fraud. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has been a huge success story since it was founded in 2010 — which is why killing the bureau was one of Project 2025’s top priorities.

We need to bring consumer protection back, stronger than before. One new issue that came to mind while putting this series together is the proliferation of BNPL -- buy now, pay later plans -- even for essentials like groceries. At a time when many families are feeling strapped, such plans aren’t going away. But they need to be regularized and policed.

Affordable cars: Let me do something shocking, and say something positive about a Trump idea: his call to make it possible for Americans to buy smaller, affordable cars. True, he has Japanese-style “tiny cars” in mind, which is a gimmick: Such cars just won’t be practical in the United States, and there’s no hint that he or anyone in his administration has given significant thought to what policies promoting automotive downsizing might require. And of course he talks only in terms of domestic production, rather than allowing import competition that might force U.S. automakers to adapt, as they did when they faced Japanese competition in the 1970s and 1980s.

Still, it’s clear that U.S. auto companies have given up on producing cars that middle-income families can afford in favor of producing high-end cars with luxury features. And the higher cost is compounded by soaring car insurance premiums and expensive repairs. , Given how auto-centric life is in most of America, the absence of affordable cars is an important factor in the affordability crisis. And at some point Americans will wonder why inexpensive cars are available in the rest of the world but not here.

sThe auto industry is on the brink of major technological change. So we should think seriously about policies that would induce US automakers to make reasonably priced cars available again.

Interest Rates and Fiscal responsibility: Finally, no discussion of affordability is complete without a mention of the current high interest rates. With higher mortgage rates, higher car loan rates and higher credit card rates, higher interest rates inflict quite a lot of economic distress on Americans. But Trump’s plan of simply ordering the Federal Reserve to cut the interest rate it controls, the Fed Funds rate, wouldn’t reduce long-term rates like mortgage rates. Even worse, it would be a recipe for future runaway inflation.

The only way to reduce the interest rate burden on household budgets without risking runaway inflation or depressing the economy is with a policy of monetary loosening accompanied with fiscal tightening. In other words, the Federal Reserve cuts the Fed Funds rate to cushion the economy, while the federal government reduces the budget deficit by increasing government revenue. Granted, that’s easier said that done. But reversing the enormous tax giveaways, that disproportionately benefit the top income brackets, would be a good start.

…

The list above is by no means comprehensive, nor does it offer remotely enough policy detail to constitute an actual program. But I hope it makes the point that there are a number of simple, conceptually easy (although in some cases politically difficult) actions that can be taken to improve affordability.

Next up: Inclusion, security and fairness.

paulkrugman.substack.com |