Carry Trade at Risk: Japan’s 10-Year JGB Yield Hits 25-Year High, Yield Curve Steepens, Finance Ministry Verbally Props Up Yen

by Wolf Richter • Dec 22, 2025 • 16 Comments

Ridiculously-behind Bank of Japan is trying to deal with a huge multi-decade monetary mess without crashing global markets

.By Wolf Richter for WOLF STREET.

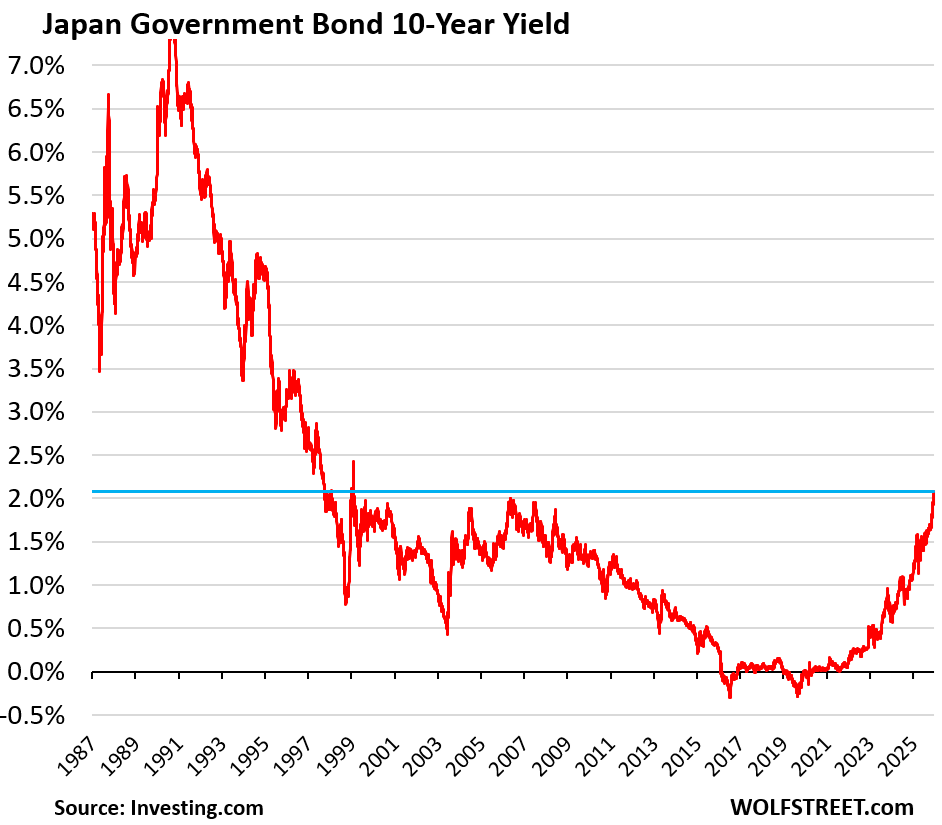

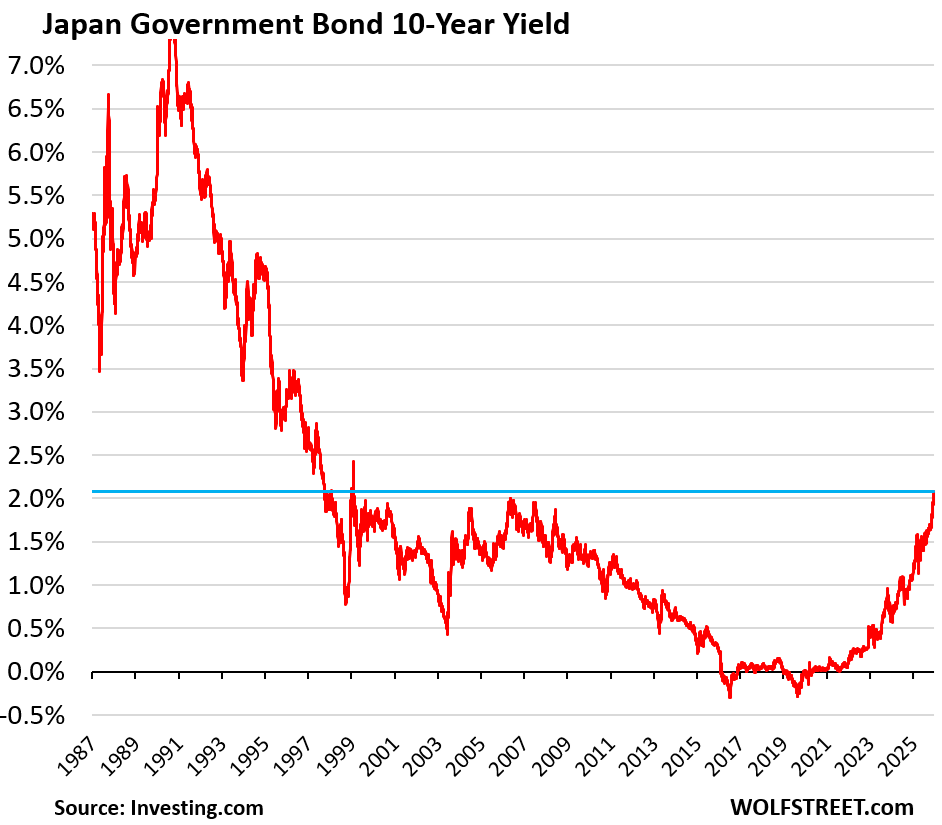

The 10-year yield of Japanese Government Bonds (JGBs) jumped 7 basis points today to 2.09%, the highest since February 1999, continuing the surge that had commenced in late 2019, back when the 10-year yield was still negative due to the Bank of Japan’s Yield Curve Control.

Inflation took off in Japan in 2021 and currently lingers at around 3.0% (core at 3.0%, overall at 2.9%), while the yen collapsed against the USD over those years. And step by step, the BOJ eased off Yield Curve Control, and then abolished it, and then hiked its main policy rate out of the negative, and started QT. On Friday, it hiked again by 25 basis points to a still ridiculously low 0.75%, the highest policy rate since 1995 – that’s how long the BOJ’s crazed monetary experiment, that it is now unwinding, has lasted! These painfully slow baby steps are leaving Japan with still deeply negative “real” interest rates across much of the JGB yield curve.

So buyers of 10-year JGBs are still far from getting compensated for inflation even at the highest yield since 1999. When yields rise, prices of existing bonds fall, and investors who’d bought the 10-year JGB back in 2019 at a negative yield bought into a sour deal.

The 10-year JGB yield is still ridiculously low, over 200 basis points below the US 10-year Treasury yield, even though inflation in the US and Japan are running at about the same pace, and Japan’s credit rating – A1 by Moody’s, A+ by S&P – is three notches worse than the USA’s blemished credit ratings of Aa1 per Moody’s and AA+ per S&P (my cheat sheet for bond credit ratings).

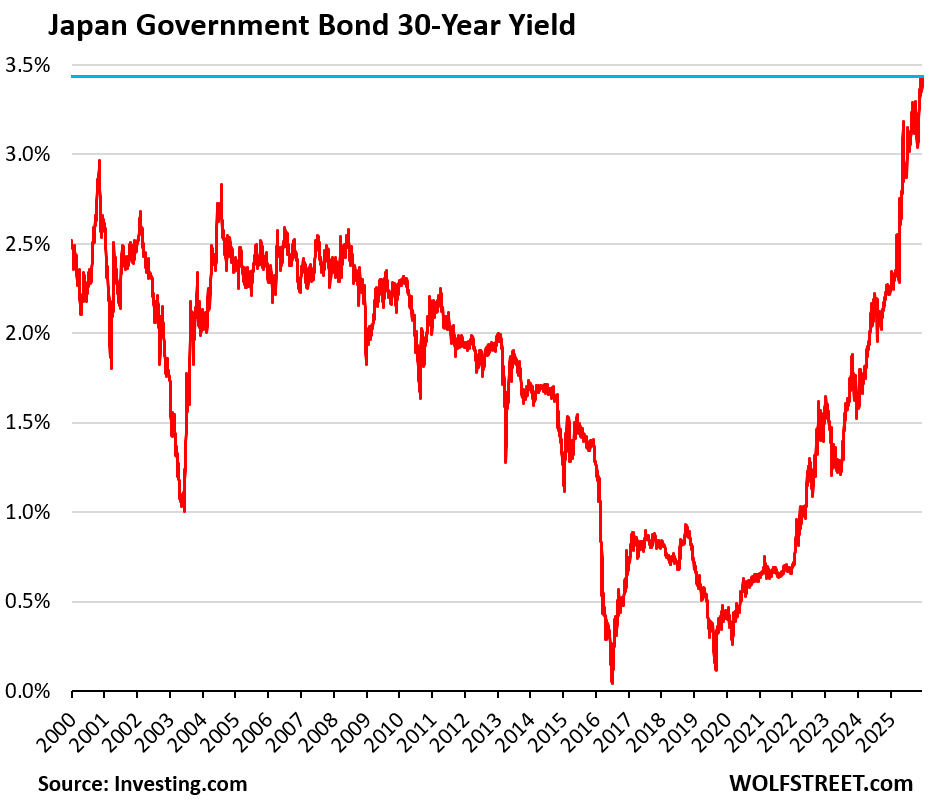

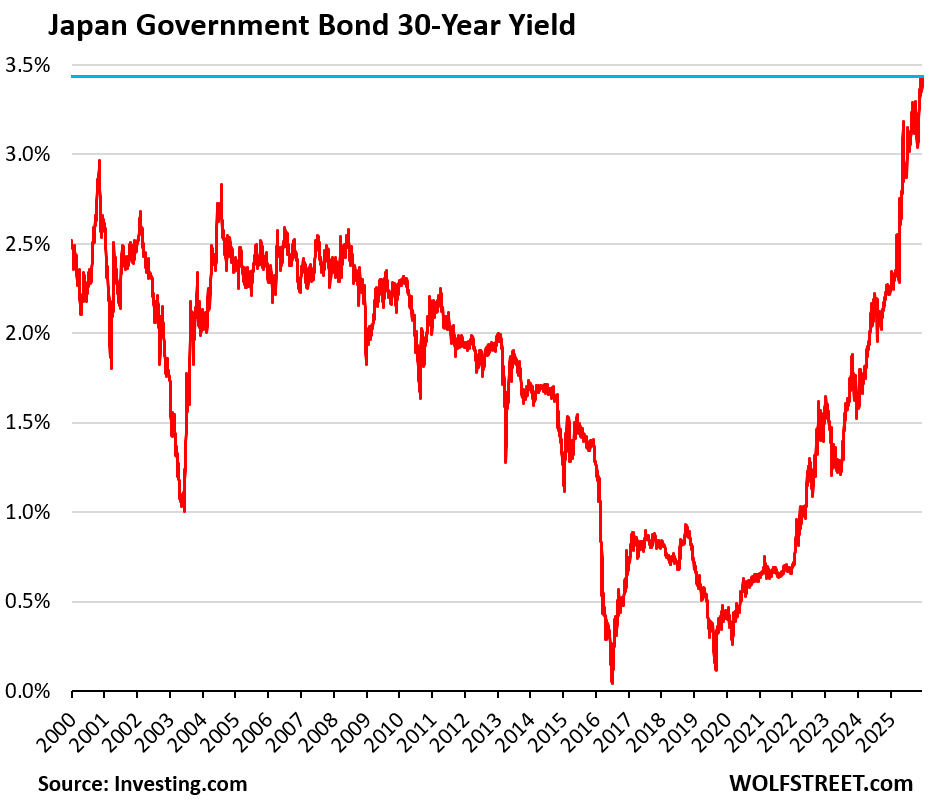

The 30-year JGB yield has risen to 3.43%, continuing the majestic spike that had commenced in August 2019, when the 30-year yield was just a hair away from turning negative.

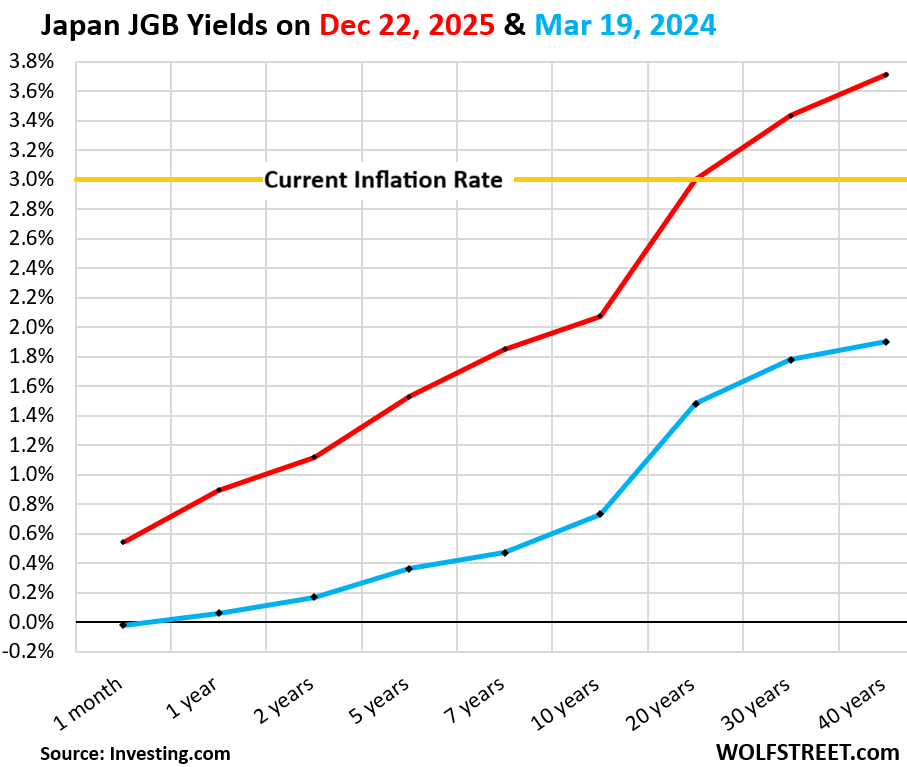

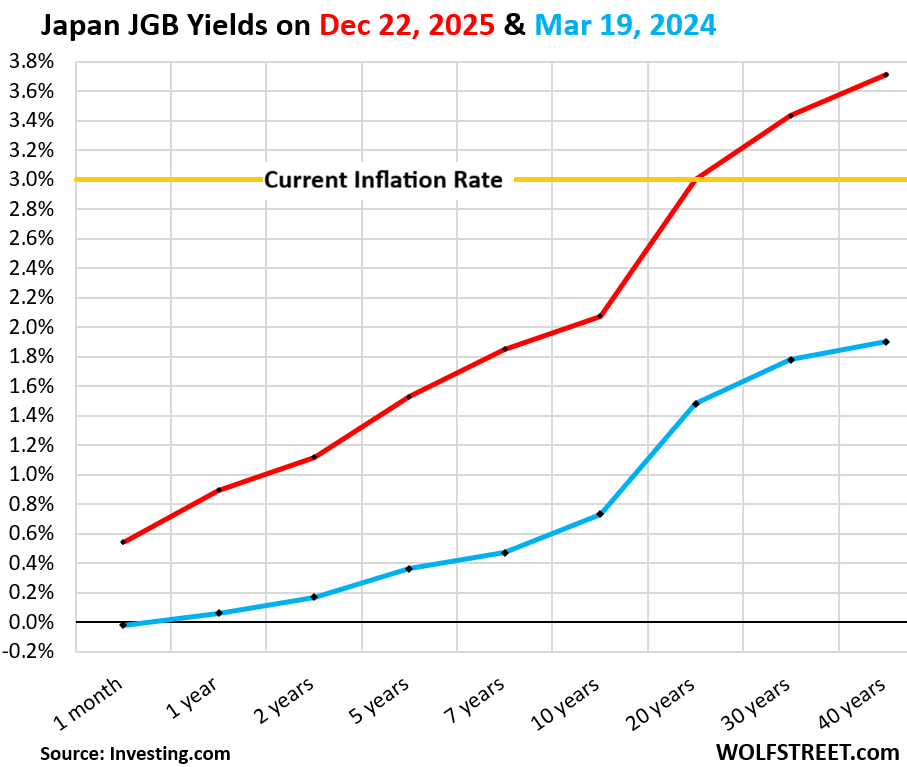

The JGB yield curve has steepened since the rate hikes began. The BOJ announced its first rake hike on March 19, 2024, to +0.1% (from -0.1%). At the time, YCC had already vanished and QT was being phased in, and long-term yields had already risen, but the 1-month yield was still -0.1% before it began to rise toward the new policy rate.

The blue line in the chart below shows key JGB yields on March 19, 2024 across the yield curve, from 1-month to 40-year yields.

The red line shows these JGB yields today, December 22.

The yield curve has steepened since March 19, 2024: the 1-month yield has risen since then by only 56 basis points, but the 10-year yield has risen by 152 basis points, the 30-year yield by 165 basis points, and the 40-year yield by 181 basis points, as the BOJ has begun unloading its JGBs.

To get a positive “real” yield at current rates of inflation, investors have to buy 25-year or longer maturities (everything above the yellow line in the chart above). These investors are now grappling with the prospect of continued and possibly hotter inflation and with the scary notion that the BOJ, which has been engaging in QT since mid-2024, surrounded by inflation, will not step back into the bond market with its relentless bid that would push bond prices back up and yields back down. That era may be over.

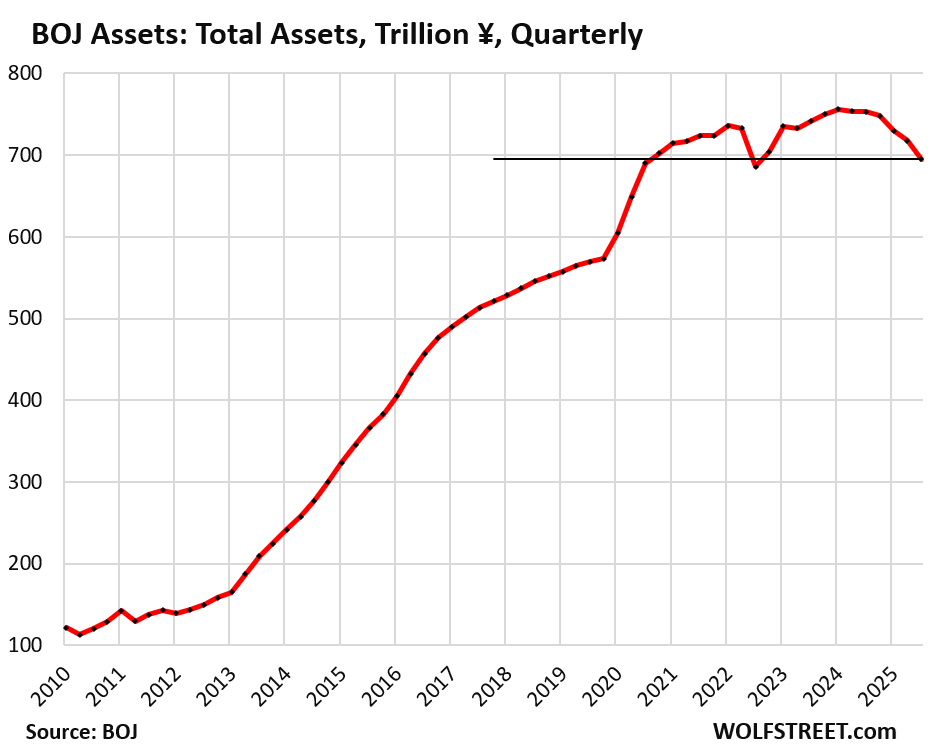

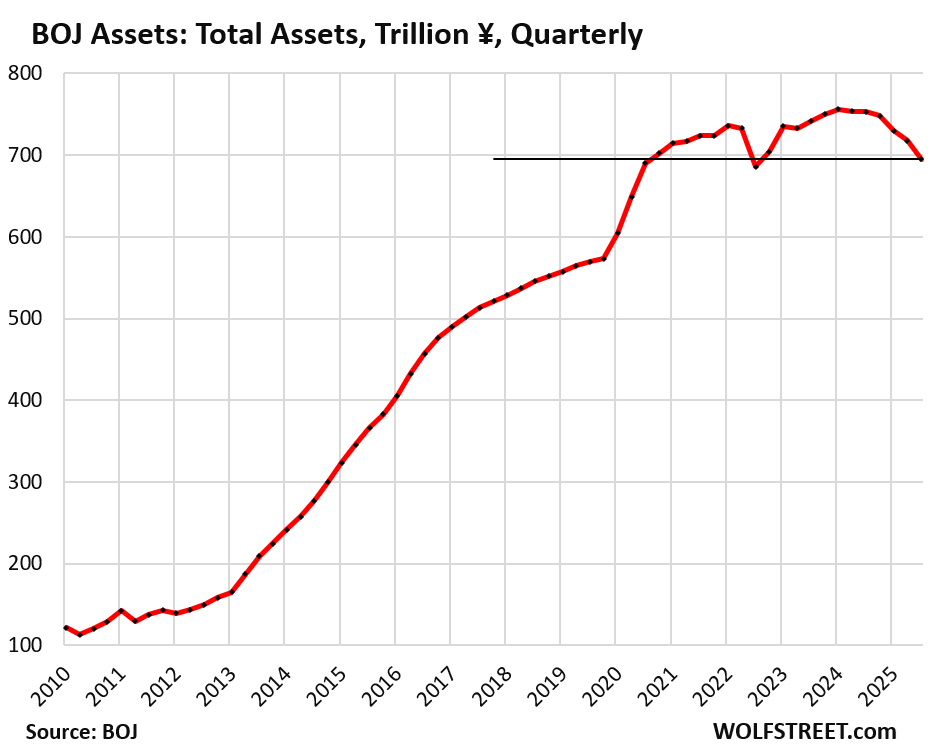

The BOJ has accelerated QT in 2025: Total assets have fallen by ¥61.2 trillion ($407 billion), or by 8.1%, to ¥695 trillion ($4.62 trillion), in its fiscal quarter through September, back to where they’d first been at the end of 2020, all in an effort to deal with the collapsing yen and tamp down on inflation.

But the BOJ still holds about 52% of all JGBs. And government-controlled entities hold another big portion of JGBs. Despite Japan’s huge debt, not all that much is in private hands.

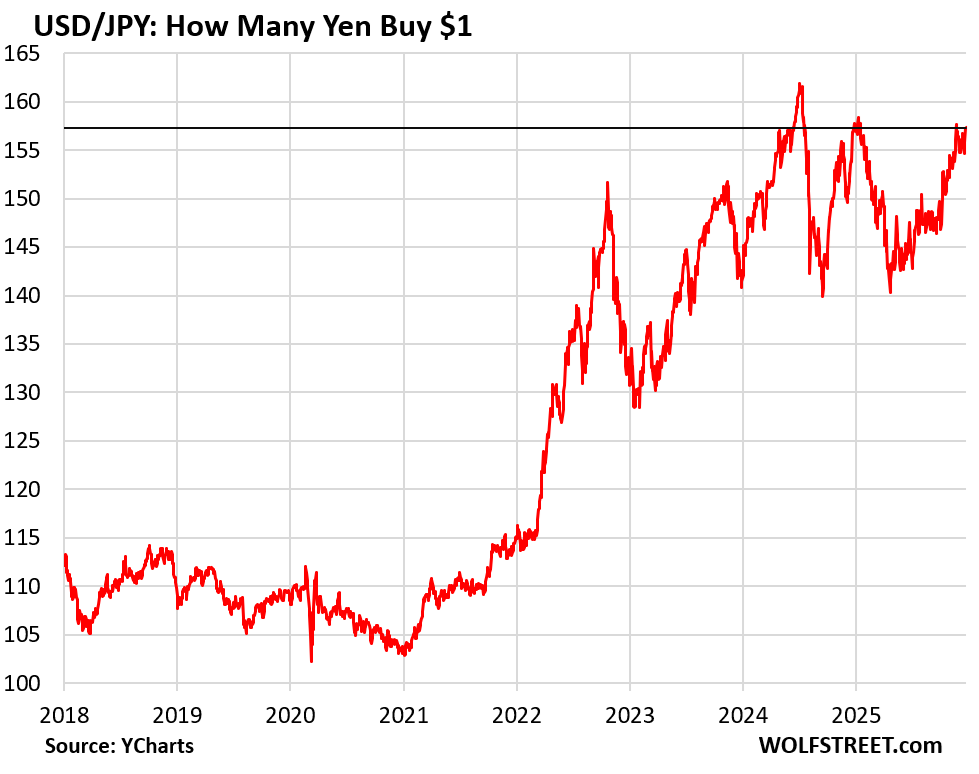

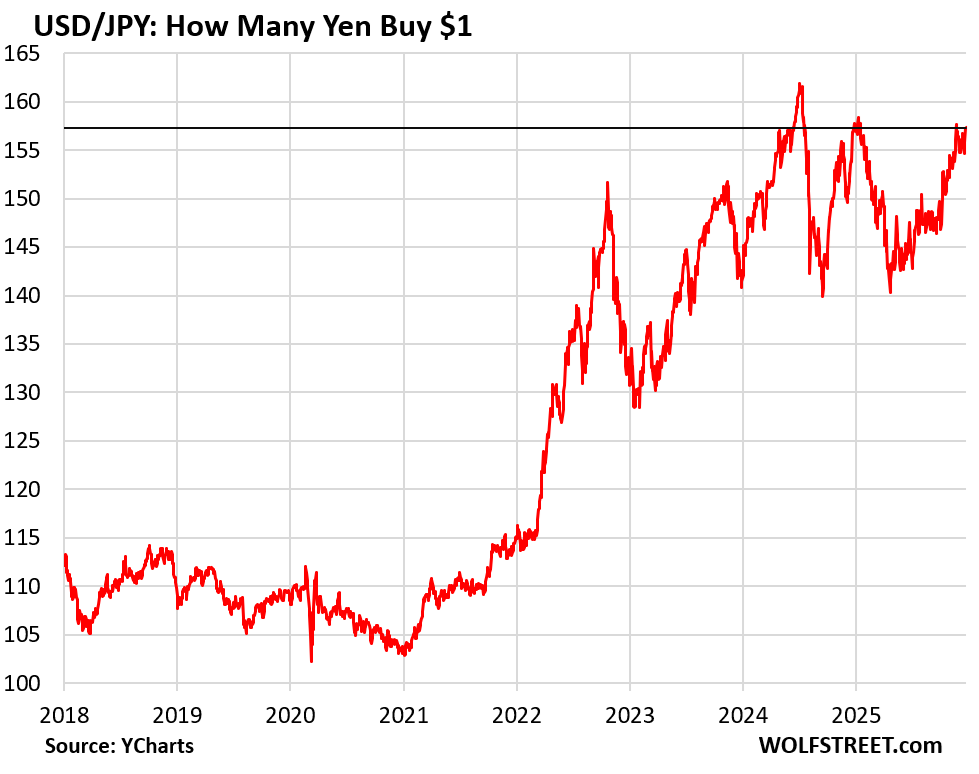

After the yen was skidding toward an exchange rate of 158 yen to the USD on Friday, Finance Minister Satsuki Katayama came out early today to prop it up verbally in an interview with Bloomberg.

“The moves were clearly not in line with fundamentals but rather speculative,” she said. “Against such movements, we have made clear that we will take bold action….”

That term “bold action” made the headlines, and the algos reacted to it and pushed the yen back up to 157 at the moment.

The yen carry trade has long thrived and along the way helped drive up asset prices in the US, and drive down US Treasury yields, as everyone from big Japanese institutions and US hedge funds, down to Japanese households, borrowed cheaply in yen, bought USD with those yen, and then bought US Treasury securities, stocks, cryptos, etc. It’s a leverage bet with multiple layers of risks.

But higher borrowing costs in Japan make the carry trade less profitable and even riskier – it always involves an exchange rate risk (that can be hedged, but at a cost) in addition to the other risks. And the higher yields in Japan are beginning to offer Japanese households and institutions a much less risky alternative to the carry trade.

The carry trade is the hot money. It can change direction at any time. Investors can sell their foreign-currency assets, exchange the USD back into yen, and pay off their yen debt, suddenly reversing capital flows. When the carry trade suddenly unwinds it can have a substantial but short-lived global impact on US yields and asset prices.

But if it unwinds slowly and over time, it means higher long-term Treasury yields and dented asset prices in the US over the longer term.

The slow systematic unwind of the carry trade – because it’s no longer attractive – doesn’t seem to have started yet in a substantial way, and if that’s the case, its impact on the Treasury market and other markets is still to come. |