Why the Sudden Emergence Sodium-Ion Batteries?

1 hour ago

Christopher Arcus 2 Comments

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

There are many questions about what is happening with sodium-ion batteries today. For example, to most people, news that CATL expects to commercialize sodium-ion batteries for EVs in 2026 with 310 mile range comes as quite a surprise.

Background

There are several different sodium-ion battery cathodes, just as there are many lithium-ion battery cathode chemistries. Lithium-ion batteries are named by their cathodes, metal oxides. Lithium-ion anodes are primarily graphite, a highly ordered form of carbon. Lithium electrolytes often consist of an organic solvent such as ethylene chloride, combined with a lithium compound. Sodium-ion batteries use a sodium compound and its own selection of solvent. In addition, some efforts are being made to substitute solid electrolytes for liquid ones, but this has not emerged yet.

Let’s look at some previous sodium-ion batteries from a few companies. Then we can get an idea of what the existing sodium-ion batteries are like for perspective before we look at what CATL has announced. Then we can see what changes were made in the new Naxtra design to assess the differences and improvements. Previously, CATL achieved 160 Wh/kg using a Prussian white and hard carbon anode, 15 minute charge to 80%, and capacity retention of over 90% to -20°C. Because of the design, it could achieve a system integration efficiency at the pack level of 80%.

Using a layered oxide cathode and hard carbon anode, Faradion achieved 155 Wh/kg, similar temperature range, and 3,000 cycle life. With polyanion and hard carbon, Tiamat achieved 90–120 Wh/kg and 5,000 cycles. Natron used a Prussian blue cathode and anode to achieve 20–30 Wh/kg and 25,000 cycle life from -20°C to 40°C. Early HiNa cells used hard carbon to create cells at 111 Wh/kg and 248 Wh/l.

Different battery chemistries have a wide range of performance specifications. Comparisons can be made with a selection of anode, cathode, and electrolyte. All sodium-ion batteries have wider temperature operation, from -40°C to 70°C with 90% retention, while lithium loses battery capacity rapidly below -10°C and is non operational at -40°C, particularly LFP. Among lithium batteries, only lithium titanate ( LTO) also does 10,000 cycles and beyond. Sodium-ion batteries are more fireproof than lithium-ion batteries. Sodium-ion batteries (SIBs) are more tolerant of voltage, and SIB allows complete discharge to zero volts. Some of SIB operate without a battery management system (BMS). This is impossible with lithium because over voltage results in fire and thermal runaway, and under voltage results in a permanently dead battery. In safety tests, sodium ion is able to withstand temperatures of several hundred degrees Celsius before burning.

Don’t try that with lithium. LFP is fairly fireproof compared to NMC, but not as fireproof as SIB. Recent stringent Chinese government safety standards for fire and explosion are met by CATL’s Naxtra sodium-ion batteries, and all but rule out NMC.

History

In 1980, Newman demonstrated reversible sodium-ion transfer in TiS2, titanium disulfide. Even though sodium-ion worked, most attention was on lithium-ion batteries, like lithium-cobalt, that achieved commercial success starting in 1991 with Sony.

One of the things that moved sodium-ion development forward was the discovery that hard carbon could be used for anodes. D. A. Stevens and Jeff Dahn research revealed glucose-based hard carbon as an anode in 2000. After 2010, research into sodium-ion chemstries increased rapidly. Faradion was founded in 2011. HiNa was founded and introduced product in 2017. By the 2020s, there were many sodium-ion battery companies, including Faradion, Natron, Northvolt, HiNa, Tiamat, Farasis, and Alsym, while CATL and BYD added sodium-ion batteries to their offerings.

Why Sodium-Ion Appeared Suddenly

Sodium-ion batteries were available as far back as 2017. While most attention was on NMC, less attention was paid to other chemistries. Sodium-ion performance increased rapidly. First-generation batteries were suitable for low-energy-density applications, with 100 to 140 Wh/kg and up to 290 Wh/l used in energy storage and e-bikes. These early SIBs used hard carbon to achieve good success, even being introduced in small cars.

HiNa and others were making headway with SIBs and they made progress in energy storage, where low energy density is not an issue. Competition for EVs and batteries is intense in China, and the market is large. The two largest battery companies in China and the world, CATL and BYD, also took note of SIBs and developed their own. They applied large research departments to SIB development.

While sodium-ion chemistry advanced, LFP made headway against NMC, encroaching at the entry level by improving cell density and taking advantage of better pack volume efficiency than NMC. The first Tesla LFP packs used Blade battery cells with 166 Wh/kg and 365 Wh/l to achieve pack density of 125 Wh/kg and a cell-to-pack mass ratio of 74%.

Researchers found that sodium could be made using the same manufacturing equipment and battery development techniques. With lower materials costs, in full production, sodium-ion batteries could achieve LFP-level performance and lower cost. HiNa states it is able to make sodium-ion batteries cheaper than lithium today by about 30 to 40%, primarily because of material cost advantages. CATL expects sodium-ion batteries to take 50% of the market from LFP batteries, which they also make. Many of the strategies and concepts used to improve lithium performance can be applied to sodium-ion and quickly improve its performance. On top of that, sodium-ion chemistry easily provides low volatility, high cycle life, and wide temperature range. Some of the tricks to improve energy density for lithium can now be applied to improving sodium. The last-generation sodium-ion chemistry was already gaining attention for energy storage, and was tantalizingly close to requirements for EVs. In reality, sodium-ion technology was developing all along, but did not quite reach the level capable of turning attention toward it until now.

Why CATL Chose Sodium Ion

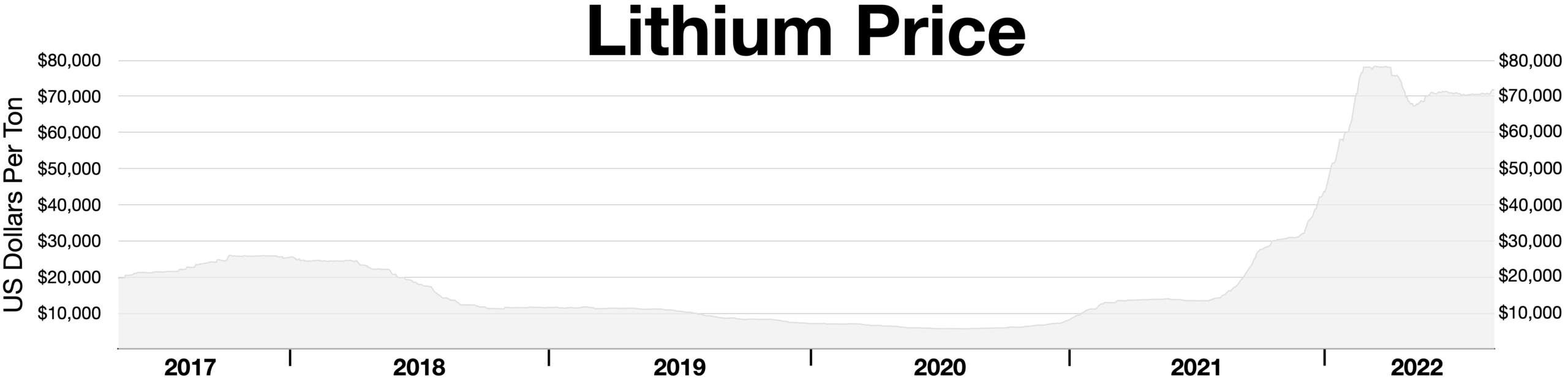

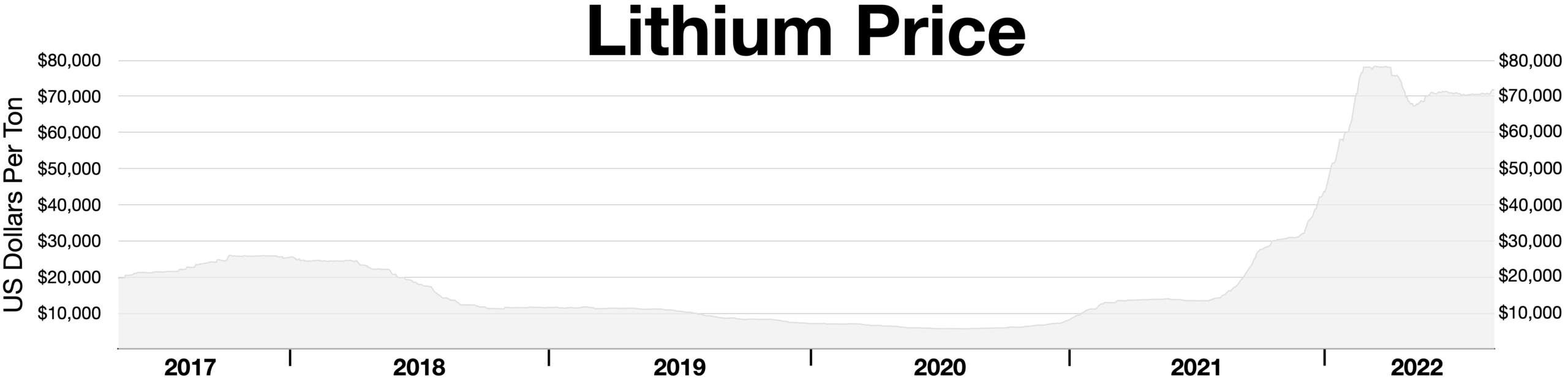

Some of the reasons CATL chose sodium-ion chemistry are material resource availability, cost, and supply stability. Now that battery production has reached high volume, steady sources of abundant, low-cost materials become more important. Sodium-ion materials are widespread and less prone to price volatility and supply interruption than materials like graphite, nickel, lithium, and cobalt. Lithium carbonate prices have proved volatile. Lithium’s recent price uptick propels sodium-ion tech forward. Sodium-ion resources like sodium carbonate and hard carbon are abundant and widespread, making supplies steady and reliable.

Lithium price volatility. Image by Wikideas1, via Wikimedia Commons ( CC0 license).

What changed in second-generation SIBs? There are a few clues. One is CATL’s announcement of self-forming anodes. This is not a hard carbon anode, a powder layered onto metal electrodes as much as 110 microns thick. Self-forming anodes are a thin layer of sodium directly deposited on the conductor. CATL says Naxtra has 60% higher volumetric density than its first-gen SIB (an increase in anode density). Earlier sodium-ion research indicates efforts could achieve volumetric density of 400 Wh/l. Unigrid sodium-ion batteries have achieved 178 Wh/kg and 417 Wh/l in full pouch cells, proving sodium-ion capabilities. Naxtra, with 175 Wh/kg, already surpasses the 166 Wh/kg first used in LFP Teslas. It may already have 356 Wh/l to match the volumetric energy density of LFP.

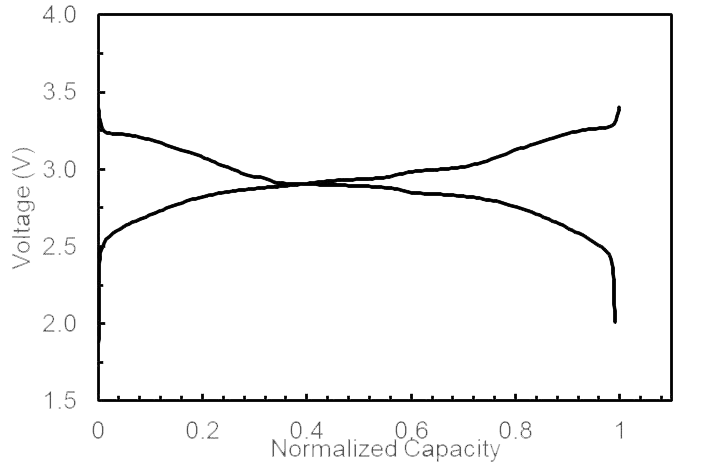

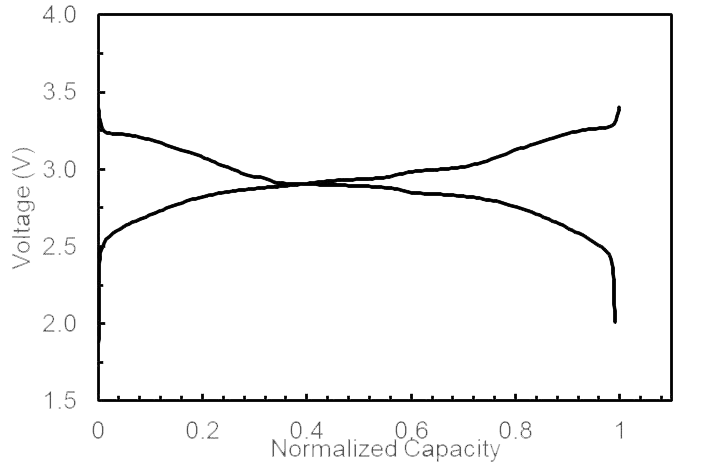

Another clue to CATL developments is patents. One patent describes the use of antimony to reduce the effect of moisture. It uses the word “reinforced” to describe how antimony works in the cathode matrix. This allows cheaper water-based production. Some of these effects also include making the discharge curve flatter, extending from 4V to about 3V, rather than down to 2V. This would make it easier to use in EVs if implemented. Unigrid sodium-ion technology employs their own proprietary methods that flatten the discharge curve.

Unigrid Narrow Cell Voltage Range. Image courtesy of Unigrid.

A late addition to this story is that the world’s first production solid-state battery (SSB) has arrived. In Donutlabs’ announcement, they make pains to point out that it is not a lithium battery and it is made from easily and ubiquitously source materials. That makes it likely it is sodium-ion. It does fit neatly into researcher expectations for sodium-ion solid state. Some social media does not understand that solid state is not a competitor to battery chemistry. These types of modern batteries all use intercalation and are differentiated by their cathode, which is a metal oxide. The cathode designates their chemistry name. So, for example, NMC is nickel manganese cobalt (oxide), LCO is lithium cobalt oxide, and LFP is lithium iron sulfate. Solid-state refers to the electrolyte. If they were solid-state, they would be NMC-SSB, for example.

Batteries are composed of a cathode, anode, and electrolyte. Up until now, all batteries used liquid electrolytes. The anode and cathode are solid. At present, sodium-ion batteries are not named by their cathodes. There are three main types of cathode — polyanion, layered oxide, and Prussian blue analogs. Really, batteries could be named by cathode, anode, and electrolyte.

Conclusion

CATL’s Naxtra already shows sodium-ion batteries advancing sooner than expected.

With added advantages of cost, greener manufacturing, safety, cycle life, temperature range, and supply stability, CATL is comfortable with entering volume sodium-ion production for use in EVs and widespread application. Overall, a combination of performance advancements put sodium-ion in contention with LFP performance at a level capable of providing cells for EVs, as CATL announced. CATL expects sodium-ion to provide over 300 miles of EV range even at cold temperatures. As volumes increase, lower material costs will widen the sodium-ion cost advantage.

Given CATL’s first-generation gravimetric energy density improved by 9%, and self-formed anodes used in the second generation increase anode volumetric density by 60%, it is conceivable that volumetric energy density has improved from 290 Wh/l to 350 Wh/l, matching or exceeding characteristics previously used for high-volume EV Blade battery packs. There is no reason to believe Naxtra does not have volumetric energy density less than some LFP Blade batteries when it exceeds LFP Wh/kg. When battery costs fall, new applications advance, like oceanic electric ships and increased energy storage with renewables, further increasing production volume. CATL’s statements regarding electric shipping indicate it expects to use volume production to lower costs to levels that support that endeavor in the next three years. By then, performance may improve further, and the virtuous cycle will continue.

cleantechnica.com |