Google Gemini generated this infographic illustrating a comparison between China and India's shift towards "electrostates" and the West's reliance on being "petrostates."

The Assumptions That Broke: China, India, and the End of Fossil Growth Models

13 hours ago

Michael Barnard

25 Comments

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

The idea that heavy freight would be the last redoubt of diesel has been repeated for decades, often with confidence and rarely with evidence. In December 2025, that idea finally collapsed. Battery-electric heavy duty trucks crossed 50% of new sales in China, a segment that had long been treated as immovable because of weight, range, duty cycles, and the presumed need for liquid fuels. This was not a pilot program, a niche urban category, or a short term policy artifact. It was a market-wide shift in the most energy-intensive road transport segment in the world’s largest vehicle market. If battery electric trucks can dominate new sales in China at that scale, then many of the assumptions that have shaped global energy debates are no longer fit for purpose.

Chart of heavy truck sales in China, assembled by author.

A couple of months ago I wrote about the astounding increase of electric heavy truck sales as a percentage of the Chinese market, but I didn’t expect the 50% point to be reached so soon. This is clearly a fleet economics and total cost of ownership story.

For years, the prevailing narrative held that China’s economy was structurally locked into fossil fuels because of its reliance on heavy industry, long haul logistics, and coal fired power. Steel, cement, and diesel freight were seen as inseparable from growth, while clean energy was framed as an additive layer that might slow emissions growth but not reverse it. That framing once had merit. China’s coal generation rose almost in lockstep with electricity demand for decades. Its steel output climbed past 1 billion tons per year. Cement production exceeded the rest of the world combined. Diesel trucks moved raw materials, intermediate goods, and finished products across vast distances. Under that model, even rapid growth in wind and solar would coexist with rising fossil fuel use.

What has happened since the early 2020s has steadily undermined that model. By 2025, China’s electricity demand was still growing at over 5% per year, roughly 520 TWh of additional consumption, GDP increased by 5%, yet coal and gas generation fell year on year. Clean power growth created a wedge of more than 6 percentage points between demand growth and fossil generation. Wind and solar generation increased by roughly 585 TWh in a single year, an amount comparable to the total annual electricity generation of France or Texas. Nuclear added another 6 TWh of new generation, hydropower around 19 TWh depending of new generation, and grid scale battery storage expanded rapidly with average new installations providing around 3 hours of duration. The result was not just cleaner electricity but a structural change in dispatch, where fossil plants ran less often and at lower utilization.

Cumulative additional TWh generation per year in China, by author.

It’s worth drawing out the nuclear vs renewables comparison. Since 2014 I’ve been tracking the natural experiment of nuclear vs renewables in China. It’s a natural experiment because it’s running in the real world. It’s a good one for the west to assess because the constraints that western nuclear advocates claim are blocking sensible nuclear barely exist in China: the country has nuclear generation as a national strategy that is nationally funded, the ability to override local concerns, and no real equivalent of the western environmental movement that grew out of the hippies and peaceniks of the 1960s and 1970s. The country has had a nuclear generation program for close to 50 and a wind and solar program for about 20 years, yet wind and solar are outstripping nuclear radically. 2025 wasn’t an especially big year for hydroelectric in China, but it outstripped nuclear too. The country, despite the narrative about China’s massive nuclear generation build out, only managed to connect a single 1.1 GW nuclear reactor to the grid last year. China’s decarbonization will be based on wind, solar and water, not nuclear, which merely plays a helping hand at still significantly less than 2% of grid capacity.

I redid the analysis this week, thinking I would publish again on this, but the chart is virtually identical, with nuclear flat along the bottom and renewables accelerating. There are clear indications solar deployments will be lower in China this year than last, but that won’t fundamentally change the curves. Renewables scale, nuclear doesn’t, in the country that eats megaprojects as mid morning snacks with tea.

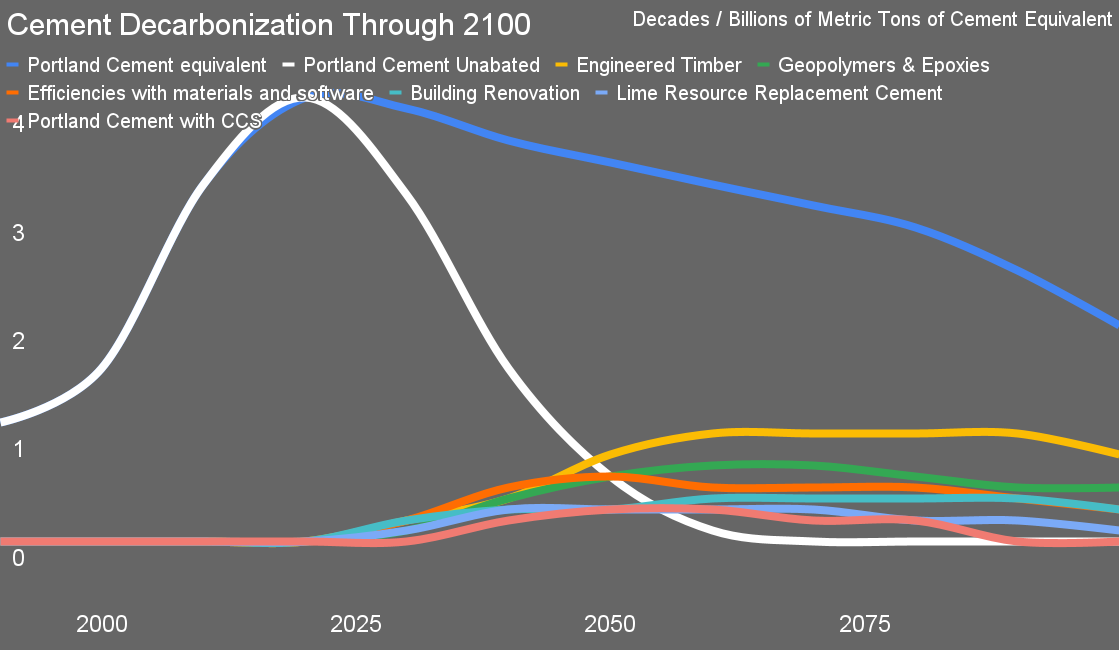

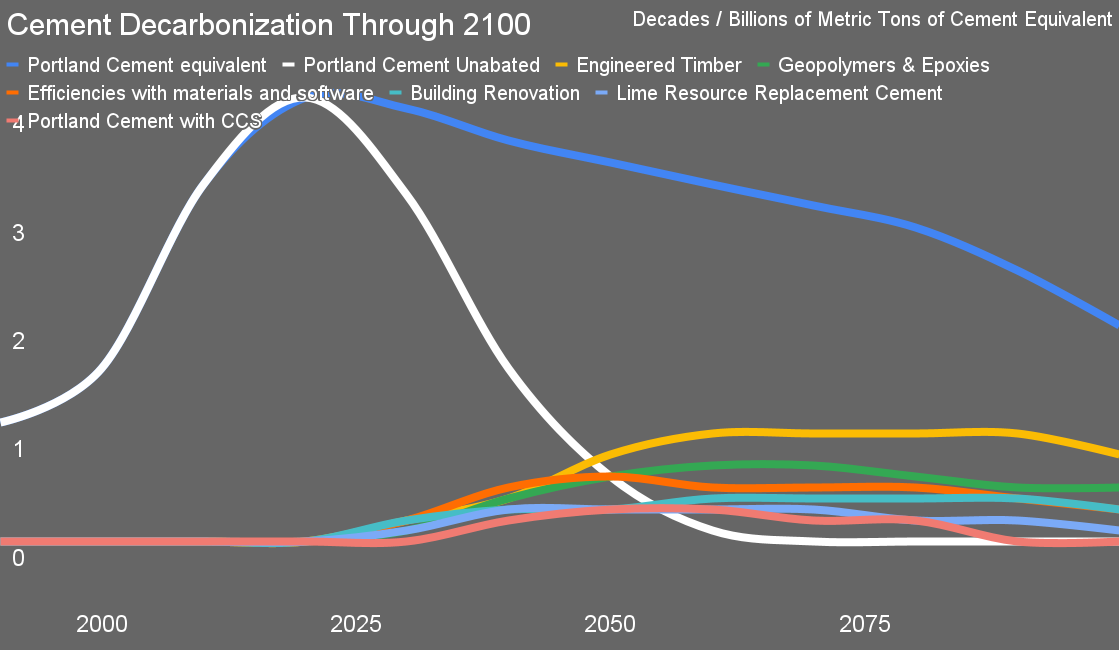

Cement displacement and decarbonization through 2100, by Michael Barnard, Chief Strategist, TFIE Strategy Inc.

At the same time, the pillars of fossil intensive industrial demand began to weaken. Steel output in China fell around 4% in 2025, with sharper declines of around 10% in some months. Cement output declined about 7% for the year. These were not temporary blips driven by weather or short term policy constraints. Fixed asset investment, which drives demand for both steel and cement, turned decisively negative by the end of the year, falling around 3.8% for the full year and likely much more in the final quarter. The long era of construction led growth in China has ended, as I pointed out in my cement and steel series, where China’s 50% market share in those commodities means that global demand curves are falling, a very good thing for decarbonization. Urbanization is mature. Housing stock is ample. Infrastructure buildout no longer expanded at double digit rates. Heavy industry is not growing as rapidly.

Fuel imports told the same story. Coal imports into China fell around 10% year on year even as domestic production barely inched up. LNG imports declined by low double digit percentages, roughly 10% to 15% depending on the data source, despite years of projections that gas would surge as a bridge fuel. Crude oil imports grew modestly, but that growth was increasingly disconnected from transport fuel demand and tied more closely to petrochemicals and exports. Diesel demand, in particular, came under pressure as efficiency improved and electrification expanded. Remember, this is against a backdrop of 5% growth in GDP, so this is not a story of economic malaise, but economic restructuring.

The crossing of the 50% threshold for battery-electric heavy duty trucks in December 2025 should be understood in this broader context. Freight is not a side story. Heavy trucks are among the largest single consumers of oil products in any economy. In China, diesel consumption historically tracked industrial output and construction activity closely. Electrifying this segment removes a major pillar of oil demand and does so with speed once the economics flip. Battery costs declined below $100 per kWh at the pack level for large format LFP systems. Electric drivetrains delivered higher efficiency, lower maintenance, and better control in stop start and grade heavy duty cycles. Total cost of ownership calculations increasingly showed savings of hundreds of thousands of yuan over the life of a truck compared to diesel equivalents, even without subsidies.

It is important to stress that this transition was not driven by environmental virtue, although that played a policy role. It was driven by cost, reliability, and industrial strategy. Chinese manufacturers built electric trucks from clean sheet designs rather than retrofitting diesel platforms. Charging infrastructure scaled alongside vehicles, often in depot based or corridor focused deployments. Grid upgrades and storage deployments ensured that electricity supply kept pace. Once electric trucks became cheaper to operate and competitive to purchase, adoption accelerated rapidly. The idea that heavy freight must rely on diesel or hydrogen simply failed in the face of real world economics.

Google Gemini generated this infographic, which outlines the key operational, economic, and market conditions required for successful battery swapping in heavy-duty transportation, including examples of suitable applications and potential failure points.

It’s also worth pointing out that at least some of this is due to battery swapping for fleets where it makes sense, mostly drayage and lower speed urban heavy trucks. China has cracked the code on heavy truck battery swapping, with national standards, governmental support and guidance and industry embrace, things the west has not remotely managed to embrace to date. I noted the conditions for success for battery swapping a couple of years ago, and China has nailed them, accelerating heavy truck electrification.

India has often been described as China ten years behind, destined to repeat the same fossil heavy growth path with a time lag. That assumption is now under similar strain. In 2025, coal fired power generation in India declined year on year for the first time outside of recessionary shocks, even as electricity demand continued to grow, the first time that coal demand has declined in both China and India. Solar and wind additions covered most incremental demand. LNG imports weakened, falling by high single digit percentages for the year with some months seeing much sharper declines. While coal capacity additions continued for energy security reasons, utilization rates came under pressure. The link between demand growth and fossil fuel growth began to loosen.

India’s transition differs from China’s in pace and scale, but not in direction. Solar and wind prices in India are among the lowest in the world. Grid scale storage is beginning to alter dispatch patterns. Electrification of transport is advancing fastest in two and three wheelers, but buses and trucks are following as battery costs fall. India is a hair under 100% heavy freight rail electrification, the only country higher than China. The notion that India must burn coal indefinitely because it is still developing ignores the way technology cost curves compress timelines. India is not replaying China’s past. It is skipping stages that no longer make economic sense.

Taken together, these developments point to a set of structural forces that are often underestimated. Electrification increases efficiency and reduces primary energy demand for the same economic output. Construction saturation reduces demand for steel and cement regardless of GDP growth. Battery and power electronics learning curves outpace those of combustion technologies. Storage changes grid behavior before capacity peaks, allowing renewables to displace fossil generation more quickly than nameplate figures suggest. Industrial overcapacity shifts output toward exports rather than sustaining domestic demand. None of these forces are cyclical. They accumulate.

Against this backdrop, many assumptions common in Western energy debates look increasingly dated. There is still a tendency to treat China and India as the main obstacles to decarbonization, places where fossil fuel growth will overwhelm progress elsewhere. There is also a tendency to assume that gas and LNG will enjoy decades of growth as transition fuels, supported by rising Asian demand. Freight electrification is often framed as slow and limited, especially outside urban niches. Just this week I listened to a commodities sector podcast I follow to hear a global LNG analyst tout China’s LNG powered trucks as a bright spot in a bleak picture, clearly missing the battery electrification underway in that segment. Battery storage is treated as helpful but marginal as well, ignoring the rather absurd amounts of grid batteries being hammered in globally, especially in China, which as always is half of the global market or more.

The data no longer supports those views. LNG demand in Asia is weakening rather than surging. Coal generation is declining in absolute terms in both China and India even as electricity demand grows. Heavy freight, once considered unelectrifiable at scale, has crossed a majority threshold in the world’s largest truck market. Clean power growth is large enough to push fossil generation down, not just slow its rise. These are not projections. They are observed outcomes.

This shift also reverses where risk lies. LNG export projects in the United States and elsewhere are betting on decades of Asian demand growth that will not materialize. Gas infrastructure faces utilization risk as electrification advances faster than expected. Western truck manufacturers that delay full battery electric platforms risk falling behind competitors who have already solved cost and performance challenges. Policy frameworks built around gradual transitions and bridge fuels may find themselves misaligned with market realities.

A more accurate mental model starts with abandoning the idea that demand growth implies fossil growth. It recognizes that electrification eats volume, not just emissions, and that storage accelerates change before capacity peaks are reached. It treats freight electrification as a leading indicator rather than a lagging one. Under this model, the most important question is not who emits more today, but who is moving faster away from the structures that lock in future emissions.

China crossing the 50% threshold for battery-electric heavy duty trucks in December 2025 did not happen because it was politically fashionable. It happened because the economics flipped and the system was ready. India is following a similar path with its own characteristics and constraints. The uncomfortable possibility for Western analysts is that some of the assumptions long applied to China and India are now obsolete, while assumptions about the pace and difficulty of transition in the West may be aging just as quickly.

cleantechnica.com |