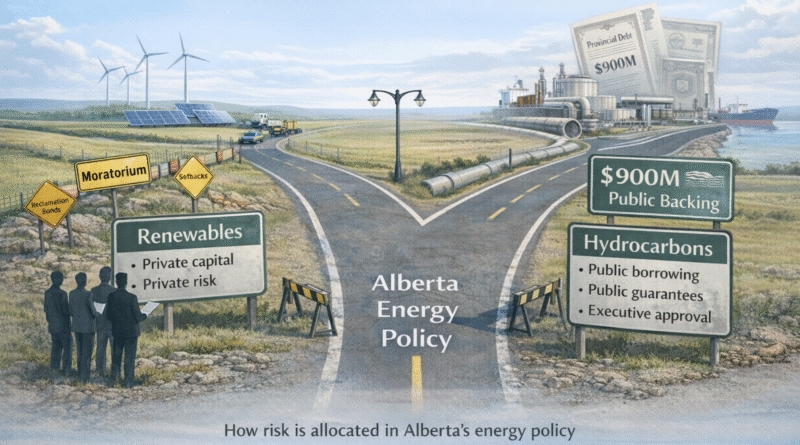

ChatGPT generated an illustration contrasting private risk for renewables with public financial backing for hydrocarbons in Alberta’s energy policy

Alberta’s $900 Million Bet: How the Province Chose Fossil Risk Over Clean Energy Markets

21 hours ago

Michael Barnard

23 Comments

Support CleanTechnica's work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Alberta’s January 2026 Order in Council authorizing expanded powers and funding for the province’s petroleum marketing agency shouldn’t exist, and if it had, it should have been a bill. Authorizing up to $900 million across borrowing, advances or investments by the Minister of Finance and provincial debt with broad powers to invest, lend, guarantee obligations, and create subsidiaries is not a technical adjustment. It is a material shift in how public risk is deployed. In Canada, changes of this scale normally go through legislative debate, estimates scrutiny, and explicit reporting requirements. Choosing an executive instrument for this package is not accidental. It avoids the friction that comes with open scrutiny and it concentrates discretion where Canadians usually expect guardrails.

The Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission (APMC) was created in 1974, in the wake of the 1970s oil shocks, as a provincial marketing board to handle the sale of Alberta’s royalty oil and gas. Its core role was deliberately narrow and technocratic: aggregate the Crown’s share of production, sell it transparently into existing markets, and maximize price realization on barrels that were already being produced, without taking on upstream risk or shaping market structure. For decades, the APMC functioned as an administrative seller and price optimizer, not a trader, investor, or market maker. It did not build infrastructure, finance counterparties, or attempt to open new markets; those activities were left to private companies operating with their own balance sheets and risk tolerance.

The choice to radically expand its role and funding sits alongside a clear pattern in Alberta’s recent energy policy. Over the past two years, the province constrained renewable electricity investment through a moratorium on new wind and solar approvals and then layered additional restrictions on top. Those projects were privately financed. They relied on private equity and project debt. They sold electricity into competitive markets or under private contracts. They did not ask for provincial borrowing, loan guarantees, or equity stakes. The public balance sheet was not exposed to construction risk, price risk, or long term asset risk. Alberta responded by increasing regulatory uncertainty, slowing deployment and adding fiscal burdens to operating renewables facilities, intentionally interfering with the market and undermining the primacy of contractual law.

Now compare that with the treatment of hydrocarbons under the Order. Instead of stepping back, Alberta steps in with its balance sheet. Instead of insisting that markets sort themselves out, the province authorizes borrowing, investing, lending, and guaranteeing to shape outcomes. This is not neutrality. It is selective intervention. Renewable energy was told to wait, absorb uncertainty, prove itself without public support and overpay for any cleanup. Hydrocarbon markets are being offered financial optionality backed by taxpayers.

The contrast is sharp because renewables asked for permits and grid access, not public money. Wind and solar projects in Alberta are built in months, not decades. They have operating lives of 20 to 30 years, modest decommissioning costs, and no fuel price exposure. If prices fall or counterparties default, investors lose money. Alberta collects lease payments, property taxes, and market fees, but does not stand behind the assets. When the province intervened, it did so to slow deployment while public exposure was already near zero.

The Order does the opposite. It reframes hydrocarbon marketing as a justification for market manipulation using public finance. Marketing in a public sector context has always meant selling what the province already owns at the best available price. It has never meant underwriting counterparties, buying equity, guaranteeing obligations, or creating subsidiaries to shape trade flows. Those are oil company functions. Calling them marketing is a sleight of hand. The province is adopting private sector fossil logic while hiding behind public sector language.

Once a government moves from selling into markets to participating in markets, risk changes character. Price volatility is no longer the main concern. Credit risk appears when buyers cannot pay. Infrastructure risk appears when assets are underused or stranded. Legal risk appears when contracts are challenged or policies change. Time risk appears because investments and guarantees often run 10, 20, or 30 years. These risks do not disappear because the participant is public. They land on taxpayers.

This is how fossil risk gets socialized. Guarantees do not show up as spending until they are called. When they are called, the liability is immediate. Investments can be written down. Borrowing magnifies exposure because debt service continues regardless of outcomes. A $900 million ceiling is large enough to matter for provincial debt levels and fiscal flexibility. In the private sector, shareholders and lenders absorb these hits. Under this structure, the public does.

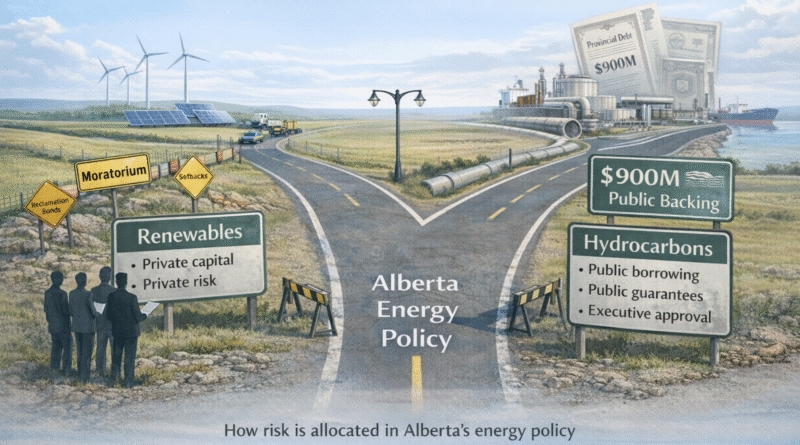

Scenarios for Alberta’s cumulative exposure to subsidies for fossil fuels under this order, by author.

All three scenarios start from the same assumptions. The $900 million limit applies only to exposure outstanding at any one time, not to cumulative activity or losses over a decade, so the authority functions as a revolving facility that can be rolled repeatedly. The analysis also assumes a tightening market for Alberta’s heavy crude, driven by electrification, refinery closures, and intensifying competition among heavy barrels in the U.S. This does not imply an abrupt collapse in demand, but it does imply greater volatility, thinner margins, and more selective buyers. The scenarios differ only in how aggressively the Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission uses the powers it has been granted.

In the first scenario, the Commission operates as a conservative marketing board, focusing on sales execution, logistics, inventory timing, and hedging to improve price realization on royalty barrels. Guarantees are rare, equity investments are avoided, and exposure is not permanently maxed out. Under these conditions, the expected fiscal outcome over ten years is close to breakeven or modestly positive, with limited downside in bad years. Given current market signals, this outcome is possible but increasingly unlikely, with a rough likelihood of 20–25%.

In the second scenario, tighter market access pushes the Commission into a defensive role. Credit support, loans, limited equity positions, and occasional guarantees are used to keep buyers and infrastructure in place as private capital becomes more cautious. The facility is heavily used and rolled continuously. While individual years may not look alarming, fiscal risk accumulates through contingent liabilities and longer-dated exposures. Over a decade, the expected outcome is negative, with losses emerging gradually rather than in a single event. Based on current trends in refinery closures and substitution, this is the most likely path, with an estimated likelihood of 45–50%.

In the third scenario, the authority evolves into a standing market-intervention tool. Subsidiaries, joint ventures, equity stakes, and guarantees are used extensively to sustain volumes and margins in a shrinking and more competitive market. The cap is respected at any one time, but exposure is constantly refinanced and politically difficult to unwind. Losses arrive through guarantee calls, impaired investments, and subsidiary unwind costs, producing large cumulative fiscal damage over ten years. This outcome is not inevitable, but it is no longer remote, with a plausible likelihood of 25–30%, especially if market conditions deteriorate faster than expected.

Taken together, the probabilities suggest that the benign outcome is no longer the base case. As market pressure increases, the balance of risk shifts toward scenarios in which taxpayers increasingly absorb costs that the private market is unwilling to bear.

In addition to most likely being a money losing proposition which will see Albertan taxpayers propping up the province’s oil and gas industry even further, this design also expands legal exposure at the worst possible time. Canada has strengthened its rules around misleading environmental and climate related representations. Enforcement focuses on the overall impression created and places the burden of proof on the party making the claim. When a province regulates, its statements are political. When a province invests, lends, or guarantees, its statements are tied to economic activity. If Alberta or its agencies describe these hydrocarbon interventions as supporting an energy transition, reducing global emissions, or aligning with climate goals, those claims become testable. Courts and regulators can ask what evidence supports them, what lifecycle analysis was done, and what counterfactuals were considered. Combining public money with loose language is no longer safe.

International climate law is closing another escape hatch. Provinces are not parties to international courts, but Canadian courts increasingly look to international rulings when judging reasonable government conduct. A growing body of jurisprudence emphasizes that governments cannot finance and enable emissions and then disclaim responsibility. Ownership, guarantees, and control strengthen attribution. By authorizing borrowing, investments, guarantees, and subsidiaries, Alberta is voluntarily tightening the link between government decisions and hydrocarbon outcomes at a moment when plausible deniability is eroding.

What makes this worse is the absence of stabilizers. Real petrostates that choose to back fossil markets with public finance rely on hard fiscal rules, large sovereign funds, and insulation from political cycles. Alberta has none of that at scale. There is no automatic diversion of upside into a protected fund. There are no embedded loss caps beyond the headline dollar limit. There is no sunset clause. This is petrostate behavior without petrostate safeguards, which is the fragile version.

There is also an ideological contradiction embedded in this move that is hard to ignore. Commodity marketing boards are not a free-market invention. They emerged from left-leaning and social-democratic traditions that were comfortable with collective action, market coordination, and public risk sharing. In Canada, agricultural marketing boards were created to pool risk among fragmented producers, stabilize prices, and counterbalance market power. They were explicit market interventions, justified as corrections where unfettered markets produced volatility or unfair outcomes. For decades, Alberta’s political culture has positioned itself against that logic, arguing that markets should clear, firms should bear risk, and governments should regulate safety and collect royalties, not trade, underwrite, or guarantee.

What makes this Order particularly jarring is that Alberta is now adopting a historically left-wing economic instrument in service of a right-wing industrial priority. The province is embracing state coordination, public borrowing, and risk socialization, but only for hydrocarbons. The usual conservative critique of government picking winners, distorting markets, and exposing taxpayers to downside risk has been set aside when fossil fuel markets face uncertainty. At the same time, privately financed renewable energy projects were told to absorb regulatory risk without public support. This selective state capitalism strips away the traditional justifications for marketing boards and exposes a deeper incoherence. Alberta is no longer arguing for markets in principle. It is arguing for markets when they discipline clean energy, and for state intervention when fossil markets need defending.

This is not energy policy coherence. It is institutional capture. The province is adopting the worldview of the industry it regulates, where market problems justify public intervention, fossil uncertainty demands support, and clean alternatives are told to wait. Canadians care about accountability, fiscal prudence, and whether public institutions exist to protect taxpayers or to underwrite a declining industry. By choosing an executive shortcut to socialize fossil risk while constraining privately financed renewables, Alberta has answered that question, even if it prefers not to say it out loud.

cleantechnica.com |