Exercise

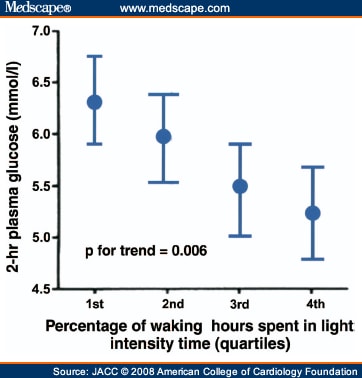

Sedentary behavior worsens insulin resistance and magnifies the post-prandial excursions of glucose and triglycerides. In contrast, exercise improves insulin sensitivity predominantly in the skeletal muscles, and acutely lowers glucose and triglyceride levels in a dose-dependent fashion. A single bout of 90 min of moderate-intensity exercise (walking briskly) within 2 h before or after a meal has been shown to lower post-prandial triglycerides and glucose levels by about 50%.[3,38] A recent study using continuous objective activity monitoring in 173 nondiabetic individuals found that cumulative daily physical activity, even light-intensity activity, was associated in a dose-dependent fashion with lower 2-h post-challenge glucose levels (but not fasting glucose levels) (Fig. 8). The same study showed that cumulative sedentary time was associated with higher 2-h glucose levels.[39]

Figure 8.

Daily Activity Reduces Post-Prandial Glucose. Cumulative daily light-intensity physical activity was inversely associated with post-prandial glucose levels. Data from Healy et al.[39]

Physical activity improves inflammation directly by lowering post-prandial glucose, and indirectly by reducing excess abdominal fat.[39] Studies show that the body will preferentially mobilize and oxidize fatty acids from adipose tissue during exercise after a low glycemic index meal rather than a high glycemic index meal.[40] Thus over time lower glycemic index diets combined with regular exercise may be useful for optimizing loss of excess visceral fat.[10,25,40]

Summary and Recommendations

The modern calorie-dense, nutrient-poor diet of processed foods, especially when combined with a sedentary lifestyle and abdominal obesity, produces exaggerated post-prandial increases in glucose and lipids, which leads to inflammation and atherosclerosis. In contrast, a diet high in minimally processed, high-fiber, plant-based foods such as low glycemic index vegetables and fruits, whole grains, legumes, and nuts will markedly blunt the post-meal increase in glucose and triglycerides. Additionally, lean protein, fish oil, calorie restriction (ideally induced via avoidance of processed foods and excessive portion sizes), weight loss, vinegar, cinnamon, tea,[41] and light to moderate alcohol intake and physical activity positively impact post-prandial dysmetabolism (Table 1).

Previous PageSection 13 of 13

Printer- Friendly Email This

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lori J. Wilson for her assistance with preparation of the manuscript and figures.

Abbreviation Notes

CAD coronary artery disease; CV cardiovascular

Reprint Address

Reprint requests and correspondence: Dr. James H. O´Keefe, 4330 Wornall Road, Suite 2000, Kansas City, Missouri 64111. E-mail: jhokeefe@cc-pc.com .

[ CLOSE WINDOW ]

References

Fito´ M, Guxens M, Corella D, et al. Effect of a traditional Mediterranean diet on lipoprotein oxidation. Arch Internal Med 2007;167: 1195–203.

Mitrou PN, Kipnis V, Thiebaut AC, et al. Mediterranean dietary pattern and prediction of all-cause mortality in a US population: results from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:2461– 8.

O´Keefe J, Bell D. The post-prandial hyperglycemia/hyperlipemia hypothesis: a hidden cardiovascular risk factor? Am J Cardiol 2007; 100:899 –904.

Bonora E, Corrao G, Bagnardi V, et al. Prevalence and correlates of post-prandial hyperglycaemia in a large sample of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 2006;49:846 –54.

Weissman A, Lowenstein L, Peleg A, Thaler I, Zimmer E. Power spectral analysis of heart rate variability during the 100-g oral glucose tolerance test in pregnant women. Diabetes Care 2006;29:571– 4.

Conaway D, O´Keefe J, Reid K, Spertus J. Frequency of undiagnosed diabetes mellitus in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:363–5.

Cowie C, Engelgau M, Rust K, et al. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in adults in the U.S. population. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1263– 8.

Cavalot F, Petrelli A, Traversa M, et al. Post-prandial blood glucose is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:813–9.

Sasso F, Carbonara O, Nasti R, et al. Glucose metabolism and coronary heart disease in patients with normal glucose tolerance. JAMA 2004;291:1857– 63.

Mellen P, Cefalu W, Herrington D. Diabetes, the metabolic syndrome, and angiographic progression of coronary artery disease in postmenopausal women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26: 189–93.

Jakulj F, Zernicke K, Bacon S, et al. A high fat meal increases cardiovascular reactivity to psychological stress in healthy young adults. J Nutr 2007;137:935–9.

Blum S, Aviram M, Ben-Amotz A, Levy Y. Effect of a Mediterranean meal on post-prandial carotenoids, paraoxonase activity and C-reactive protein levels. Ann Nutr Metab 2006;50:20–4.

Ceriello A, Assaloni R, Ros RD, et al. Effect of atorvastatin and irbesartan, alone and in combination, on post-prandial endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in type 2 diabetic patients. Circulation 2005;111:2518 –24.

Dilley J, Ganesan A, Deepa R, Sharada G, Williams O, Mohan V. Association of A1C with cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome in Asian Indians with normal glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1527–32.

Bansal S, Buring J, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks F, Ridker P. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA 2007;298:309 –16.

Nordestgaard B, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 2007;198:299 –308.

Monnier L, Mas E, Ginet C, et al. Activation of oxidative stress by acute glucose fluctuations compared with sustained chronic hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2006;295:1681–7.

Brownlee M, Hirsch I. Glycemic variability: a hemoglobin A1cindependent risk factor for diabetic complications. JAMA 2006;295: 1707–8.

Lichtenstein A, Appel L, Brands M, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation 2006;114:82–96.

O´Keefe J, Cordain L. Cardiovascular disease resulting from a diet and lifestyle at odds with our Paleolithic genome: how to become a 21st-century hunter-gatherer. Mayo Clin Proc 2004;79:101– 8.

Beulens J, Bruijne LD, Stolk R, et al. High dietary glycemic load and glycemic index increase risk of cardiovascular disease among middleaged women. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:14 –21.

Jenkins D, Kendall C, Faulkner D, et al. Long-term effects of a plant-based dietary portfolio of cholesterol-lowering foods on blood pressure. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007 Apr 25;[E-pub ahead of print].

Bayard V, Chamorro F, Motta J, Hollenberg N. Does flavonol intake influence mortality from nitric oxide-dependent processes? Ischemic heart disease, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and cancer in Panama. Int J Med Sci 2007;4:53– 8.

Hlebowicz J, Darwiche G, Björgell O, Almér L-O. Effect of cinnamon on post-prandial blood glucose, gastric emptying, and satiety in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1552– 6.

Arora S, McFarlane S. The case for low carbohydrate diets in diabetes management. Nutr Metab 2005;2:16 –24.

Galgani J, Aguirre C, Dý´az E. Acute effect of meal glycemic index and glycemic load on blood glucose and insulin responses in humans. Nutr J 2006;5:22– 8.

Ma Y, Griffith J, Chasan-Taber L, et al. Association between dietary fiber and serum C-reactive protein. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:760–6.

Josse A, Kendall C, Augustin L, Ellis P, Jenkins D. Almonds and post-prandial glycemia—a dose-response study. Metabolism 2007;56: 400–4.

Jenkins D, Kendall C, Josse A, et al. Almonds decrease post-prandial glycemia, insulinemia, and oxidative damage in healthy individuals. J Nutr 2006;136:2987–92.

Park Y, Harris W. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation accelerates chylomicron triglyceride clearance. J Lipid Res 2003;44:455– 63.

Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, et al. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomized open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet 2007;369:1090–8.

Östman E, Granfeldt Y, Persson L, Björck I. Vinegar supplementation lowers glucose and insulin responses and increases satiety after a bread meal in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:983– 8.

Nilsson M, Holst J, Björck I. Metabolic effects of amino acid mixtures and whey protein in healthy subjects: studies using glucose-equivalent drinks. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:996 –1004.

Fontana L, Klein S. Aging, adiposity, and calorie restriction. JAMA 2007;297:986 –94.

Meyer T, Kova´cs S, Ehsani A, Klein S, Holloszy J, Fontana L. Long-term caloric restriction ameliorates the decline in diastolic function in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:398–402.

O´Keefe J, Bybee K, Lavie C. Alcohol: the razor-sharp double-edged sword. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:1009 –14.

Brand-Miller J, Fatima K, Middlemiss C, et al. Effect of alcoholic beverages on post-prandial glycemia and insulinemia in lean, young, healthy adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1545–51.

Levine J. Exercise: a walk in the park? Mayo Clin Proc 2007;82: 797–8.

Healy G, Dunstan D, Salmon J, et al. Objectively measured lightintensity physical activity is independently associated with 2-h plasma glucose. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1384 –9.

Stevenson E, Williams C, Mash L, Phillips B, Nute M. Influence of high-carbohydrate mixed meals with different glycemic indexes on substrate utilization during subsequent exercise in women. Am J Nutr 2006;84:354–60.

Byrans JA, Judd PA, Ellis PR. The effect of consuming instant black tea on postprandial plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in healthy humans. J Am Coll Nutr 2007;26:471–7.

Author Information

James H. O´Keefe, MD, Neil M. Gheewala, MS, and Joan O. O´Keefe, RD, from the Mid America Heart Institute and University of Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(3) ©2008 Elsevier Science, Inc. |