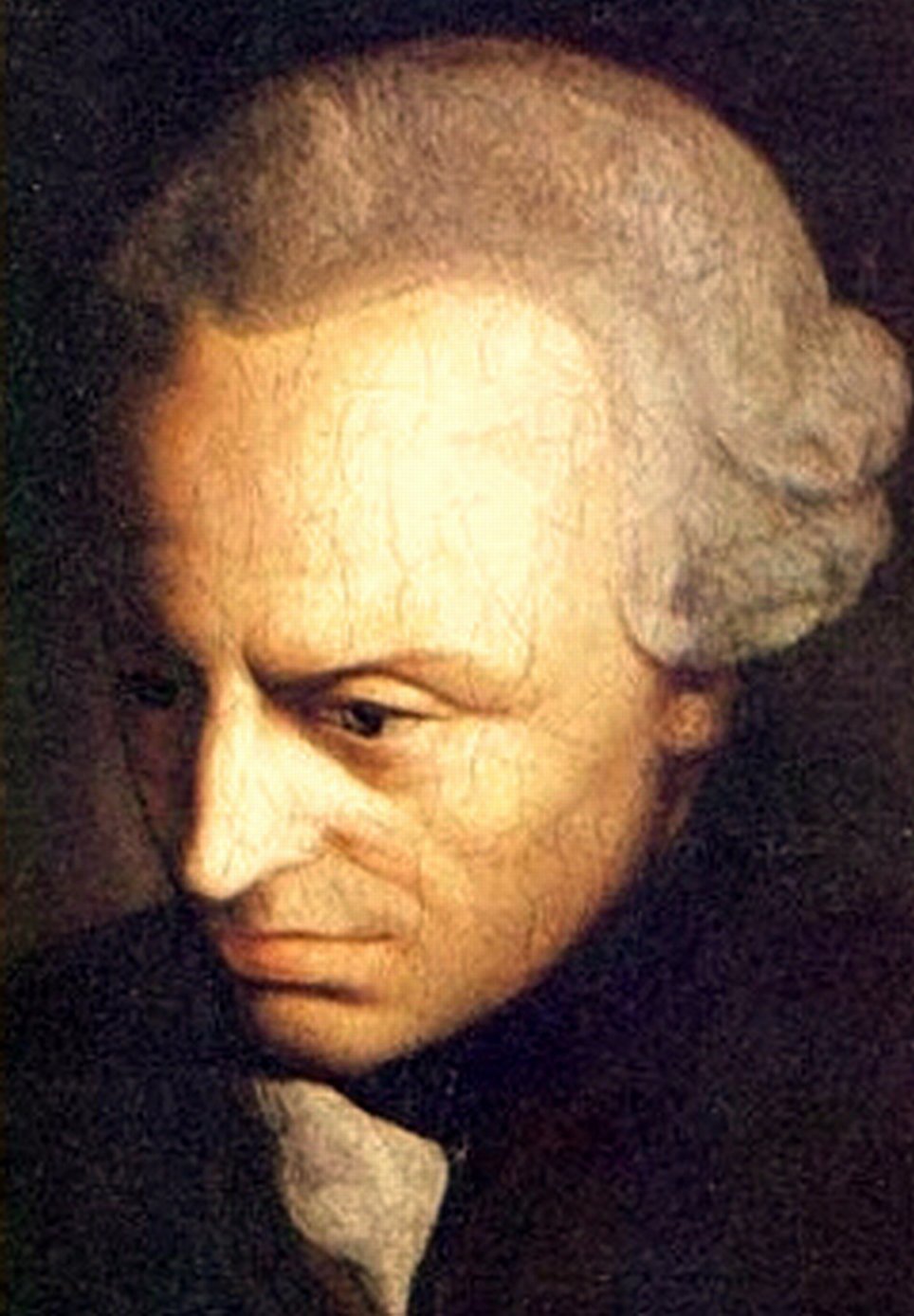

Immanuel Kant was a german racist.

"Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race. The yellow Indians have a smaller amount of talent. The Negroes are lower, and the lowest are a part of the American peoples." (Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View)

"The race of the American cannot be educated. It has no motivating force, for it lacks affect and passion. They are not in love, thus they are also not afraid. They hardly speak, do not caress each other, care about nothing and are lazy."

3.0 Kant and Race

Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race. The yellow Indians have a smaller amount of talent. The Negroes are lower, and the lowest are a part of the American peoples. (Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View)

Before we can proceed any further in our investigation into the upshot of Kant’s empirical studies, it becomes important to head off one principle objection; namely, that criticizing Kant for his particular racial views is as fruitful and enlightening as chastising a fourth century Roman plebeian for holding a belief in the geocentric model of the solar system. In other words, that criticizing Kant for his racial biases is anachronistic. Although there is some truth to this claim, I feel this particular objection is based on a misunderstanding of this current project. What is of importance here is not whether Kant the man subscribed to the European culture of racism dominant during his lifetime. Rather, what is of interest is what Kant the philosopher and scholar viewed as the result of his "study of man", and that study’s implications for his moral theory. Quite often passages, such as the one quoted above, are introduced as evidence for the claim that Kant the man was indeed and sexist/racist. But to better understand the distinction I wish to maintain, one has simply to note that the above excerpt (as distasteful and blatantly fallacious as it may seem to readers at the tail end of the twentieth century) is still compatible with the idea that all humans fall under the larger category of rational being. Differences in natural cognitive capacity, some may argue, are not inconsistent with the belief that non-Europeans are still rational; that is, still capable of moral agency. To this I must concur. However, if it can be discovered that Kant in fact did not believe that certain races of human beings were capable of achieving the status of moral agent as a result of their membership to their particular race, then our task not only is relevant, but also extremely important to the next generation of Kantian scholarship.

The quote used to open this section was not intended to be simply pejorative. In fact, in our present context it serves directly to introduce an important doctrine of the Kantian empirical anthropology - the classification of the races. That Kant had created his own systematization of the human races, in and of itself, is of little surprise in a culture fascinated by taxonomy and the apparent order of the natural world. The reason Kant’s version is of particular interest, however, is that he sought to create a system of taxonomy free from what he perceived to be the central flaw of all others. Specifically, he attempted to provide a "logical grounding" for his natural and racial classification. This was precisely what he believed Linnaeus had failed to accomplish.

Kant details this racial taxonomy in his 1775 essay On the Different Races of Man. Therein he claims that "it is necessary to assume only four races of man," which he constructs as follows:

STEM GENUS: white brunette

First Race, very blond (northern Europe), of damp cold.

Second race, Copper-red (America), of dry cold.

Third race, Black (Senegambia), of dry heat.

Fourth race, Olive-yellow (Indians), of dry heat.

Emmanuel Eze, in his masterful explication of Kant’s theory of race, maintains the above division to be structured upon a deeper assumption; namely, that Kant believed that "the ideal skin color is the ‘white’ (the white brunette) and the others are superior or inferior as they approximate whiteness." Although Eze’s essay clearly demonstrates that Kant indeed believed in the natural inferiority of several of the non-European (non-blond) races, his argument stops short of defending the claim that this "inferiority" amounts to an entire lack of moral agency. The important question for our purposes, however, is whether or not this ‘natural inferiority’ is indicative of the lack of moral character? An adequate response to this question, I believe, can be obtained by considering the two essential characteristics of all rational beings noted earlier, namely, (i) will and (ii) reason.

As before, will is to be understood as the ability to transcend the heteronomy of the empirical world (i.e., the laws of nature and natural causation). Although the individual determination of whether or not a given being possesses this motivating force is solely a matter of inductive inference, Kant still seems to think that we can be reasonably certain of our conclusions. He makes this clear when he claims, in his Philosophische Anthropologie, that "when a people does not perfect itself in any way over the space of centuries, so it may be assumed that there exists a certain natural predisposition (analage) that the people cannot transcend." Empirical evidence of a particular race’s failure to act upon moral duties (both perfect and imperfect) over an extended period of time, then, can be seen as indicative of their lack of autonomy of the will. Indeed, Kant clearly dictates that one cannot (without contradiction) be both a rational being (one who follows the formulations of the categorical imperative), and a being who wills that all give themselves up to natural inclination. The result of this, Kant believes, would put the moral agent in the same position of the "south sea islanders" wherein "every man should let his talents rust and should be bent on devoting his life solely to idleness, indulgence, procreation, and, in a word, to enjoyment." But Kant stresses that this is exactly what a rational being would not do, for all rational beings desire that their powers should be developed since "they serve him, and are given him, for all sorts of possible ends." It should be noted here, that I am not maintaining that all moral agents necessarily act in accordance with the moral law. Kant clearly states that only a "divine will" would have such a nature. Rather, I am simply connecting the dots (so to speak) between Kant’s anthropological and practical philosophies by claiming: Although lack of development of a race is not (in and of itself) indication that its members lack the requisite autonomy of will, continued and sustained failure to do so is.

Does Kant give us any indication (besides his rather harsh assessment of the ‘south sea islanders’) that there are, in fact, certain races which exhibit such an apparent inability to "transcend" the natural world of sense and inclination? That is, are there races which apparently lack the minimal standard of will? Here, a few additional excerpts from his Philosophische Anthropologie become relevant. For instance, when discussing the indigenous population of the Americas, Kant maintains:

The race of the American cannot be educated. It has no motivating force, for it lacks affect and passion. They are not in love, thus they are also not afraid. They hardly speak, do not caress each other, care about nothing and are lazy. (Emphasis added)

Here, Kant appears to be constructing a inductive inference regarding the status of an entire race (what he calls the copper-red race). Also, in a much earlier work, Kant comments that (when discussing the American natives) "an extraordinary apathy constitutes the mark of this type of race." His pronouncements, then, that the tribes of the Americas were "lazy", "cannot be educated", "lack a motivating force", and are "apathetic" more than suggest that members of the copper-red race lack the will requisite to transform mere beings into autonomous beings. To this assertion can be juxtaposed Kant’s proclamation that "the white race possesses all motivating forces and talents in itself." It seems apparent then, at least with regards to native Americans, that Kant applies his dictum that if a race consistently fails to improve itself, it can safely be assumed they are in fact unable to do so. If a race indeed did possess a certain "predisposition", which they were unable to overcome, would this be consistent with the doctrine that moral agency demands freedom of the will? Here, it seems clear, the answer is no. For, if the copper-red race is indeed uneducable, possessing none of the motivating force enjoyed by the white race, and, furthermore, unable to transcend this condition, it seems entirely unreasonable to conclude that they were still beings endowed with the necessary free will. If we are to take Kant’s "ought implies can" seriously, then, certainly the poor members of the copper-red race must not fall under the umbrella of "moral agents", as they cannot act otherwise; their collective "predisposition" prohibiting any attempt to transcend the heteronomy of the natural world. Thus, we may consider this our first clear example where, for Kant, race determines moral agency/personhood.

The copper-race, native to the Americas, appears to lack the autonomy necessary for moral agency. But when Kant considers the black race, indigenous to Africa, an entirely different problem arises. For Kant, the black race is "completely the opposite of the Americans," in that they are "full of affect and passion, very talkative, lively and vain. . . [and] have many motivating forces." Immediately, it appears we are dealing rational beings, as compared to the zombie-esqe, ‘brutish’ native Americans. But, when discussing the possibility of educating the black race, Kant qualifies his earlier statements by claiming: "They can be educated but only as servants (slaves), that is they allow themselves to be trained." Eze points out Kant’s distinction, here, between "to educate oneself" and "to be trained by someone else." Self-education would require not only autonomous will, but also reason. Training, on the other hand, does not require reason; only that the subject have the appropriate desire to be trained (i.e., will). Does Kant take the black race to be incapable of achieving the level of rationality required of moral agents? A few examples should suffice to demonstrate that, whether or not he believed them to possess an autonomous will, Kant still held the black race to be incapable of achieving the required level of rationality.

In a notoriously famous passage, Kant introduces us to a Negro carpenter who was fond of ridiculing the white clergy for the manner in which they treated their wives. "You whites are indeed fools," Kant has his carpenter say, "for first you make great concessions to your wives, and afterward you complain when they drive you mad." In lieu of addressing the specific merits of the carpenters claim, Kant simply dismisses the gentleman with the comment that "…in short, this fellow was quite black from head to foot, a clear proof that he was stupid." This abrupt, dismissive attitude that Kant displays towards all members of the black race supports the contention that he certainly believed them to be sub-par cognitively. This interpretation is consistent with his remarks a few pages earlier when he states: "So fundamental is the difference between these two races of man (whites and Negroes), and it appears to be as great in regard to mental capacities as in color." This inheirent cognitive deficiency by itself, however, is not sufficient to show a complete lack of rationality. But, Kant adds further credence to this assertion when he attempts to provide instructions of the proper method of disciplining Negro servants. Here Kant "advises us to use a split bamboo cane instead of a whip, so that the ‘Negro’ will suffer a great deal of pains. . .but without dying." In fact, Kant goes to great lengths to describe the manner in which the cane is to be prepared in order for it to be most effective. Does this behavior seem to be in line with Kant’s formulation of his practical imperative, namely, that we are to "always treat humanity whether in your own person or in the person of any other, never simply as a means, but always at the same time as an end"? If the function of reason is to "produce a will which is good" , then, arguably, its lack would necessitate such drastic treatment of the black servants in effort to force their will toward the good. Clearly, it appears to be becoming more difficult to reconcile Kant’s various comments with the view that he still considered members of the black race to be members of his "kingdom of ends." And, as further support for the claim that he did not consider blacks to be participating moral agents due to their insufficient rational capacity, one need only read Kant’s discussion of the contributions (or lack thereof) blacks have made to humanity. Here, he expressly agrees with Hume that it is impossible to

. . . cite a single example in which a Negro has shown talents, and. . . that among the hundreds of thousands of blacks who have been transported elsewhere from their countries, although many of them have been set free, still not one was ever found who presented anything great in art or science or any other praiseworthy quality.

The only reasonable conclusion left to be drawn from all this is that Kant considered the members of the black race to inherently lack the required level of rationality to be considered moral agents. The problem of universalizing the maxim "You ought to whip other rational beings with a split-bamboo cane," is really not a problem at all if the recipients of the beating are not true rational beings; that is, are members of the rationally deficient black race.

msu.edu |