Proof of heaven popular, except with the church

By John Blake, CNN

“God, help me!”

Eben Alexander shouted and flailed as hospital orderlies tried to hold him in place. But no one could stop his violent seizures, and the 54-year-old neurosurgeon went limp as his horrified wife looked on.

That moment could have been the end. But Alexander says it was just the beginning. He found himself soaring toward a brilliant white light tinged with gold into “the strangest, most beautiful world I’d ever seen.”

Alexander calls that world heaven, and he describes his journey in “Proof of Heaven,” which has been on The New York Times bestseller list for 27 weeks. Alexander says he used to be an indifferent churchgoer who ignored stories about the afterlife. But now he knows there’s truth to those stories, and there’s no reason to fear death.

“Not one bit,” he said. “It’s a transition; it’s not the end of anything. We will be with our loved ones again.”

Heaven used to be a mystery, a place glimpsed only by mystics and prophets. But popular culture is filled with firsthand accounts from all sorts of people who claim that they, too, have proofs of heaven after undergoing near-death experiences.

Yet the popularity of these stories raises another question: Why doesn’t the church talk about heaven anymore?

Preachers used to rhapsodize about celestial streets of gold while congregations sang joyful hymns like “I’ll Fly Away” and “When the Roll is Called up Yonder.” But the most passionate accounts of heaven now come from people outside the church or on its margins.

Most seminaries don’t teach courses on heaven; few big-name pastors devote much energy to preaching or writing about the subject; many ordinary pastors avoid the topic altogether out of embarrassment, indifference or fear, scholars and pastors say.

“People say that the only time they hear about heaven is when they go to a funeral,” said Gary Scott Smith, author of “Heaven in the American Imagination” and a history professor at Grove City College in Pennsylvania.

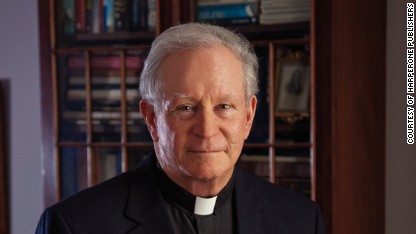

Talk of heaven shouldn’t wait, though, because it answers a universal question: what happens when we die, says the Rev. John Price, author of “Revealing Heaven,” which offers a Christian perspective of near-death experiences.

“Ever since people started dying, people have wondered, where did they go? Where are they now? Is this what happens to me?” said Price, a retired pastor and hospital chaplain.

A little girl’s revelation

Price didn’t always think heaven was so important. He scoffed at reports of near-death experiences because he thought they reduced religion to ghost stories. Besides, he was too busy helping grieving families to speculate about the afterlife.

His attitude changed, though, after a young woman visited his Episcopal church one Sunday with her 3-year-old daughter.

Price had last seen the mother three years earlier. She had brought her then-7-week-old daughter to the church for baptism. Price hadn't heard from her since. But when she reappeared, she told Price an amazing story.

She had been feeding her daughter a week after the baptism when milk dribbled out of the infant's mouth and her eyes rolled back into her head. The woman rushed her daughter to the emergency room, where she was resuscitated and treated for a severe upper respiratory infection.

Three years later, the mother was driving past the same hospital with her daughter when the girl said, “Look, Mom, that’s where Jesus brought me back to you.”

“The mother nearly wrecked her car,” Price said. “She never told her baby about God, Jesus, her near-death experience, nothing. All that happened when the girl was 8 weeks old. How could she remember that?”

When Price started hearing similar experiences from other parishioners, he felt like a fraud. He realized that he didn’t believe in heaven, even though it was part of traditional Christian doctrine.

He started sharing near-death stories he heard with grieving families and dejected hospital workers who had lost patients. He told them dying people had glimpsed a wonderful world beyond this life.

The stories helped people, Price said, and those who've had similar experiences of heaven should “shout them from the rooftops.”

“I’ve gone around to many churches to talk about this, and the venue they give me is just stuffed,” he said. “People are really hungry for it.”

Why pastors are afraid of heaven

Many pastors, though, don’t want to touch the subject because it’s too dangerous, says Lisa Miller, author of “Heaven: Our Enduring Fascination with the Afterlife.”

Miller cites the experience of Rob Bell, one of the nation’s most popular evangelical pastors.

John Price ignored heaven until he met a woman with an amazing story.

Bell ignited a firestorm two years ago when he challenged the teaching that only Christians go to heaven in “Love Wins: A Book About Heaven, Hell, and the Fate of Every Person Who Ever Lived.”

The book angered many members of Bell’s church as well as many in the evangelical establishment. He subsequently resigned.

“Farewell, Rob Bell,” one prominent evangelical tweeted.

“It’s a tough topic for a pastor,” said Miller, a former religion columnist for the Washington Post. “If you get too literal, you can risk sounding too silly. If you don’t talk about it, you’re evading one of the most important questions about theology and why people come to church.”

If pastors do talk about stories of near-death experiences, they can also be seen as implying that conservative doctrine – only those who confess their faith in Jesus get to heaven, while others suffer eternal damnation – is wrong, scholars and pastors say.

Many of those who share near-death stories aren’t conservative Christians but claim that they, too, have been welcomed by God to heaven.

“Conservative Christians aren’t the only ones going to heaven," said Price, "and that makes them mad."

There was a time, though, when the church talked a lot more about the afterlife.

Puritan pastors in the 17th and 18th centuries often preached about heaven, depicting it as an austere, no fuss-place where people could commune with God.

African-American slaves sang spirituals about heaven like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” They often depicted it as a place of ultimate payback: Slaves would escape their humiliation and, in some cases, rule over their former masters.

America’s fixation with heaven may have peaked around the Civil War. The third most popular book in 18th century America – behind the Bible and “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” – was "Gates Ajar," written in the wake of the war, Miller says.

The 1868 novel was “The Da Vinci Code” of its day, Miller says. It revolved around a grieving woman who lost her brother in the Civil War. A sympathetic aunt assures her that her brother is waiting in heaven, a bucolic paradise where people eat sumptuous meals, dogs sun themselves on porches and people laugh with their loved ones.

“This was a vision of heaven that was so appealing to hundreds of thousands of people who had lost people in the Civil War,” Miller said.

Americans needed heaven because life was so hard: People didn’t live long, infant mortality was high, and daily life was filled with hard labor.

“People were having 12 kids, and they would outlive 11 of them,” said Smith, author of "Heaven in the American Imagination." “Death was ever-present.”

The church eventually stopped talking about heaven, though, for a variety of reasons: the rise of science; the emergence of the Social Gospel, a theology that encouraged churches to create heaven on Earth by fighting for social justice; and the growing affluence of Americans. (After all, who needs heaven when you have a flat-screen TV, a smartphone and endless diversions?)

But then a voice outside the church rekindled Americans' interest in the afterlife. A curious 23-year-old medical student would help make heaven cool again.

The father of near-death experiences

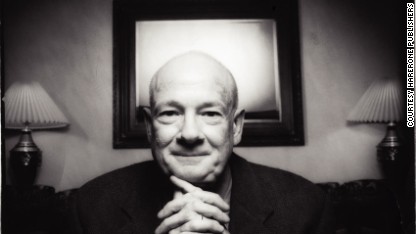

Raymond Moody had been interested in the afterlife long before it was fashionable.

He was raised in a small Georgia town during World War II where death always seemed just around the corner. He constantly heard stories about soldiers who never returned from war. His father was a surgeon who told him stories of bringing back patients from the brink of death. In college, he was enthralled when he read one of the oldest accounts of a near-death experience, a soldier’s story told by Socrates in Plato’s “Republic.”

His fascination with the afterlife was sealed one day when he heard a speaker who would change his life.

The speaker was George Ritchie, a psychiatrist. Moody would say later of Ritchie, “He had that look of someone who had just finished a long session of meditation and didn’t have a care in the world.”

Moody sat in the back of a fraternity room as Ritchie told his story.

It was December 1943, and Ritchie was in basic training with the U.S. Army at Camp Barkeley, Texas. He contracted pneumonia and was placed in the hospital infirmary, where his temperature spiked to 107. The medical staff piled blankets on top of Ritchie’s shivering body, but he was eventually pronounced dead.

“I could hear the doctor give the order to prep me for the morgue, which was puzzling, because I had the sensation of still being alive,” Ritchie said.

He even remembers rising from a hospital gurney to talk to the hospital staff. But the doctors and nurses walked right through him when he approached them.

He then saw his lifeless body in a room and began weeping when he realized he was dead. Suddenly, the room brightened “until it seemed as though a million welding torches were going off around me.”

He says he was commanded to stand because he was being ushered into the presence of the Son of God. There, he saw every minute detail of his life flash by, including his C-section birth. He then heard a voice that asked, “What have you done with your life?"

After hearing Ritchie’s story, Moody decided what he was going to do with his life: investigate the afterlife.

Raymond Moody revived interest in heaven by studying near-death experiences.

He started collecting stories of people who had been pronounced clinically dead but were later revived. He noticed that the stories all shared certain details: traveling through a tunnel, greeting family and friends who had died, and meeting a luminous being that gave them a detailed review of their life and asked them whether they had spent their life loving others.

Moody called his stories “near-death experiences,” and in 1977 he published a study of them in a book, “Life after Life.” His book has sold an estimated 13 million copies.

Today, he is a psychiatrist who calls himself “an astronaut of inner space.” He is considered the father of the near-death-experience phenomenon.

He says science, not religion, resurrected the afterlife. Advances in cardiopulmonary resuscitation meant that patients who would have died were revived, and many had stories to share.

“Now that we have these means for snatching people back from the edge, these stories are becoming more amazing,” said Moody, who has written a new book, “Paranormal: My Life in Pursuit of the Afterlife.”

“A lot of medical doctors know about this from their patients, but they’re just afraid to talk about it in public.”

Ritchie’s story was told through a Christian perspective. But Moody says stories about heaven transcend religion. He's collected them from Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and atheists.

“A lot of people talk about encountering a being of light,” he said. “Christians call it Christ. Jewish people say it’s an angel. I’ve gone to different continents, and you can hear the same thing in China, India and Japan about meeting a being of complete love and compassion.”

It’s not just what people see in the afterlife that makes these stories so powerful, he says. It’s how they live their lives once they survive a near-death experience.

Many people are never the same, Moody says. They abandon careers that were focused on money or power for more altruistic pursuits.

“Whatever they had been chasing, whether it's power, money or fame, their experience teaches them that what this (life) is all about is teaching us to love,” Moody said.

Under 'the gaze of a God'

Alexander, the author of “Proof of Heaven,” seems to fit Moody's description. He’s a neurosurgeon, but he spends much of time now speaking about his experience instead of practicing medicine.

He'd heard strange stories over the years of revived heart attack patients traveling to wonderful landscapes, talking to dead relatives and even meeting God. But he never believed those stories. He was a man of science, an Episcopalian who attended church only on Easter and Christmas.

That changed one November morning in 2008 when he was awakened in his Lynchburg, Virginia, home by a bolt of pain shooting down his spine. He was rushed to the hospital and diagnosed with bacterial meningitis, a disease so rare, he says, it afflicts only one in 10 million adults.

After his violent seizures, he lapsed into a coma — and there was little hope for his survival. But he awakened a week later with restored health and a story to tell.

He says what he experienced was “too beautiful for words.” The heaven he describes is not some disembodied hereafter. It’s a physical place filled with achingly beautiful music, waterfalls, lush fields, laughing children and running dogs.

In his book, he describes encountering a transcendent being he alternately calls “the Creator” or “Om.” He says he never saw the being's face or heard its voice; its thoughts were somehow spoken to him.

“It understood humans, and it possessed the qualities we possess, only in infinitely greater measure. It knew me deeply and overflowed with qualities that all my life I’ve always associated with human beings and human beings alone: warmth, compassion, pathos … even irony and humor.”

Holly Alexander says her husband couldn’t forget the experience.

“He was driven to write 12 hours a day for three years,” she said. “It began as a diary. Then he thought he would write a medical paper; then he realized that medical science could not explain it all.”

“Proof of Heaven” debuted at the top of The New York Times bestseller list and has sold 1.6 million copies, according to its publisher.

Alexander says he didn’t know how to deal with his otherworldly journey at first.

“I was my own worst skeptic,” he said. “I spent an immense amount of time trying to come up with ways my brain might have done this.”

Conventional medical science says consciousness is rooted in the brain, Alexander says. His medical records indicated that his neocortex — the part of the brain that controls thought, emotion and language — had ceased functioning while he was in a coma.

Alexander says his neocortex was “offline” and his brain “wasn’t working at all” during his coma. Yet he says he reasoned, experienced emotions, embarked on a journey — and saw heaven.

“Those implications are tremendous beyond description,” Alexander wrote. “My experience showed me that the death of the body and the brain are not the end of consciousness; that human experience continues beyond the grave. More important, it continues under the gaze of a God who loves and cares about each one of us.”

Skeptics say Alexander’s experience can be explained by science, not the supernatural.

They cite experiments where neurologists in Switzerland induced out-of-body experiences in a woman suffering from epilepsy through electrical stimulation of the right side of her brain.

Michael Shermer, founder and publisher of Skeptic magazine, says the U.S. Navy also conducted studies with pilots that reproduced near-death experiences. Pilots would often black out temporarily when their brains were deprived of oxygen during training, he says.

These pilots didn’t go to heaven, but they often reported seeing a bright light at the end of a tunnel, a floating sensation and euphoria when they returned to consciousness, Shermer says.

“Whatever experiences these people have is actually in their brain. It’s not out there in heaven,” Shermer said.

Some people who claim to see heaven after dying didn’t really die, says Shermer, author of “Why People Believe Weird Things.”

“They’re called near-death experiences for a reason: They’re near death but not dead,” Shermer said. “In that fuzzy state, it’s not dissimilar to being asleep and awakened where people have all sorts of transitory experiences that seem very real.”

The boy who saw Jesus

Skeptics may scoff at a story like Alexander’s, but their popularity has made a believer out of another group: the evangelical publishing industry.

While the church may be reluctant to talk about heaven, publishers have become true believers. The sales figures for books on heaven are divine: Don Piper’s “90 Minutes in Heaven” has sold 5 million copies. And “Heaven is for Real: A Little Boy’s Astounding Story of His Trip to Heaven and Back” is the latest publishing juggernaut.

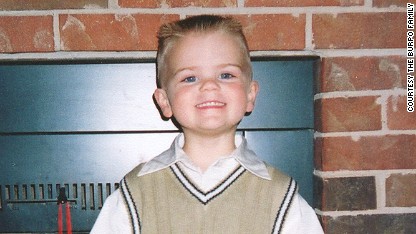

Colton Burpo says he saw heaven and describes the color of Jesus' eyes.

“Heaven is for Real” has been on The New York Times bestseller list for 126 consecutive weeks and sold 8 million copies, according to its publisher.

The story is told from the perspective of Colton Burpo, who was just 4 when he slipped into unconsciousness while undergoing emergency surgery for a burst appendix.

Colton says he floated above his body during the operation and soared to heaven, where he met Jesus. Todd Burpo, Colton’s father, says he was skeptical about his son’s story until his son described meeting a great-grandfather and a miscarried baby sister — something no one had ever told him about.

Todd Burpo is a pastor, but he says he avoided preaching about heaven because he didn’t know enough about the subject.

“It’s pretty awkward,” he said. “Here I am the pastor, but I’m not the teacher on the subject. My son is teaching me.”

Colton is now 13 and says he still remembers meeting Jesus in heaven.

“He had brown hair, a brown beard to match and a smile brighter than any smile I’ve ever seen,’’ he said. “His eyes were sea-blue, and they were just, wow.”

Colton says he’s surprised by the success of his book, which has been translated into 35 languages. There’s talk of a movie, too.

“It’s totally a God thing,” he said.

Alexander, author of “Proof of Heaven,” seems to have the same attitude: His new life is a gift. He’s already writing another book on his experience.

“Once I realized what my journey was telling me," he said, "I knew I had to tell the story.”

He now attends church but says his faith is not dogmatic.

“I realized very strongly that God loves all of God’s children,” he said. “Any religion that claims to be the true one and the rest of them are wrong is wrong.”

Central to his story is something he says he heard in heaven.

During his journey, he says he was accompanied by an angelic being who gave him a three-part message to share on his return.

When he heard the message, he says it went through him “like a wind” because he instantly knew it was true.

It’s the message he takes today to those who wonder who, or what, they will encounter after death.

The angel told him:

“You are loved and cherished, dearly, forever.”

“You have nothing to fear.”

“There is nothing you can do wrong."

religion.blogs.cnn.com |