Brazil: 10 good reasons to think the two-month-old government will go

Jonathan Wheatley | Feb 25 18:15

So much is going wrong in Brazil that it is hard to keep up. For years, critics have accused the government of incompetence. Now its actions are looking catastrophic – so much so that there are good reasons to think President Dilma Rousseff, who began a second four-year term only on January 1, may not last much longer.

Here is our list of 10 things that threaten to bring her down.

1. Politics.

For a Brazilian president to be impeached, they must do something egregiously wrong. But many do that and survive. What really counts is losing support in Congress. Rousseff’s congressional majority was cut at the election while the number of parties in Congress increased, leaving her coalition more splintered and harder to control. Worse, large sections of her ruling Workers’ Party have turned against her. Some members regard her as a late-coming, opportunistic interloper. Some to the “right” of the party accuse her of messing up. Others to the left are furious at her appointment of the “neo-liberal” Joaquim Levy as finance minister last month.

On Tuesday evening, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, her mentor and predecessor in the presidency, told her publicly to “hold her head up”. She should leave the scandal at Petrobras to others and remember that she had won the election. “Dilma cannot and should not be bothered [by the scandal], or else we’ll be paralysed,” he warned.

Lula made the comments in a speech to a labour union rally “in support of Petrobras and of Brazil” – and, presumably, of Rousseff. But his comments reveal deep frustration with the president, who has been absent from public view for long periods since the campaign.

2. Petrobras

Also on Tuesday evening, Moody’s Investors Service became the first of the three big global credit rating agencies to downgrade Petrobras to junk. Fitch and Standard & Poor’s are expected to follow. We won’t rehearse the corruption scandal here, the biggest and most damaging in Brazilian history. Enough to say it now threatens to spiral out of control.

At issue for Moody’s (among much else) was the question of when, if ever, Petrobras will file audited financial statements for 2014. Failure to do so would tip the emerging world’s biggest corporate borrower into default. The statement from Moody’s was damning:

Moody’s does not perceive substantial progress that would significantly reduce concern about the potential for payment acceleration under debt agreements that require the provision of audited financial statements… Moody’s does not yet see any concrete assurance that audited statements will be available by any particular date.

Rousseff told reporters on Wednesday that the downgrade showed a lack of understanding by Moody’s and that Petrobras would recover from its setbacks “with no great consequences”. Others regard a downgrade of Petrobras as tantamount to a downgrade of Brazil, with similarly damaging consequences.

If Congress did move to impeachment, Petrobras would provide the egregious sin: Rousseff was president of the board when most of the alleged corruption took place.

3. Consumer confidence.

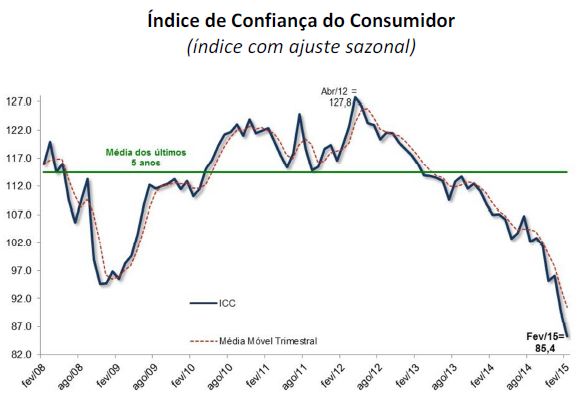

Consumers are extremely fed up, as shown by a monthly survey released on Wednesday by the Brazilian Institute of Economics at the Fundação Getulio Vargas, an educational institution.

Source: FGV IBRE Source: FGV IBRE

The FGV blamed inflation, high interest rates, fear of unemployment and the risk of water and energy rationing (see below).

4. Inflation

Twenty years ago, inflation in Brazil was about 3,000 per cent a year. Many Brazilians are too young to remember, but others are not. Some now fear the government has abandoned its inflation target of 4.5 per cent a year. On Tuesday, the national statistics office said inflation in the month to February 15 was 1.33 per cent, and 7.36 per cent during the previous 12 months – much higher than expected.

5. Unemployment

Many Brazilians have hitherto been prepared to forgive the government for inflation and slow growth because they felt their own jobs were secure. But with the economy expected to contract by 0.5 per cent this year, employers have started laying workers off. An estimated net 26,000 jobs were lost in January, usually a month of hiring rather than firing. This poses a big challenge to Rousseff’s popularity.

Signs of worker unrest are multiplying. Lorry drivers have gone on strike, blocking highways around the country, with dangerous knock-on effects across the economy.

6. Investor confidence

Business daily Valor Econômico reported on Friday that the Treasury had sold 10m short-duration bills maturing in October this year, to a value of R$9.3bn ($3.2bn), with an average annual yield of more than 13 per cent. This was the biggest single auction of such short-term debt since “at least 2000? according to Valor, which said the government was being forced to sell ever shorter yielding bonds as investors worried about its ability to meet its budget targets.

7. The budget

Last year, Brazil delivered its first primary budget deficit in more than a decade, effectively taking the country back to the dark days before it began to implement at least a semblance of fiscal discipline. Successive governments have strained to achieve primary surpluses (before debt payments) big enough to keep the ratio of debt to GDP on a downward course. But the Rousseff administration appeared to give up the ghost last year, with a primary deficit equal to 0.63 per cent of GDP and a nominal deficit, including debt repayments, equal to 6.7 per cent of GDP.

8. The economy

That the economy is imploding goes almost without saying. Investors had hoped that the appointment of the Chicago-trained Levy to the finance ministry would turn things around. Many still hold out that hope. But the task looks increasingly daunting. More to the point, Levy has appeared as a lonely figure, the one man in government holding his finger in the dyke. Rousseff did not even turn up at the announcement of his appointment. She was there at the formal ceremony to mark it, as this all-headline, no-text press release illustrates. But a search of Google Images suggests they have not been seen in public together since then.

9. Water

The sensation of approaching apocalypse in Brazil is underlined by a shortage of water afflicting the city of São Paulo. The main reservoir system serving the city, the country’s biggest, spent several weeks at just 6 per cent of its capacity before rains in the past few days brought some relief. It is now at 11 per cent. But the water company, Sabesp, warned on Wednesday that this was far from enough. Residents tell tales of sudden cut-offs, and of having to carry buckets of water up flights of stairs. The authorities say rationing is not in place; citizens say it is. Everyone knows rainfall has been unusually scarce over the past several months. But the cause is not low rainfall alone. An estimated one third of the water in the Sabesp system is lost to leaks. Bad management and a failure to invest are also to blame.

10. Electricity

The last time a government was brought down (though at the ballot box rather than by impeachment) the prime cause was electricity rationing. Fernando Henrique Cardoso, swept into office in 1994 on the success of his inflation-beating Plano Real, lost to Lula in 2002 after a summer of electricity rationing brought on by a combination of low rainfall – power generation in Brazil relies overwhelmingly on hydroelectric dams – bad management and a failure to invest. The Rousseff administration may avoid a similar fate. Or it may not.

The last president of Brazil to be impeached was Fernando Collor de Mello in 1992. He led a playboy lifestyle surrounded by colourful, mafioso-style characters (some of whom died colourful, mafioso-style deaths). He was impeached (after resigning to avoid losing his political rights – he is now back in the Senate) on suspicion of running an influence-peddling scheme. His situation was quite different from Rousseff’s. But what undid Collor was not his involvement in corruption but the revulsion felt for him among the people and, especially, among a majority in Congress. Rousseff must be very careful not to go the same way.

Back to beyondbrics

Tags: Brazil economy, corruption, Dilma Rousseff, Petrobras

Posted in Brazil, Latin America and the Caribbean | Permalink |