Fear and Loathing of Negative-Yield Debt: Bond Trader's Dilemma

by

Lukanyo Mnyanda

Eshe Nelson

It’s not as if Christoph Kind relishes putting his clients’ money into bonds that often pay nothing in interest and can all but guarantee losses.

But Kind is doing just that -- and he’s hardly the only one.

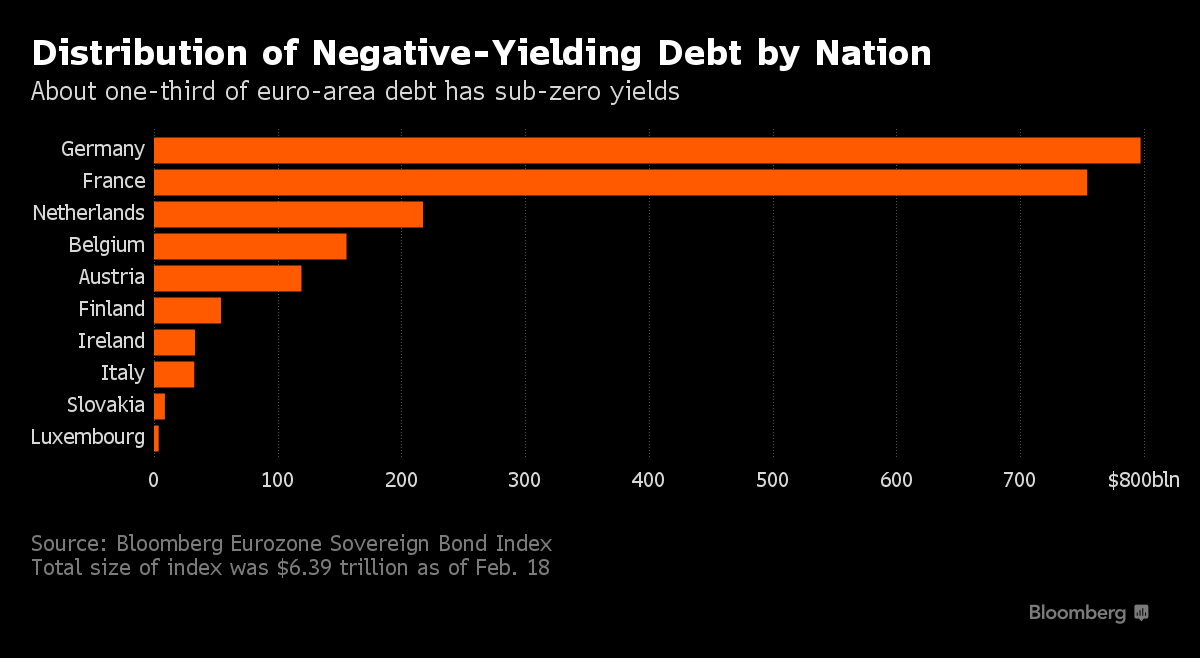

More and more, debt investors are being confronted by a new reality where deepening concern over the global economy has made sub-zero interest rates the norm. In Germany, Kind’s home market, surging haven demand has pushed average yields on about a trillion euros ($1.2 trillion) of debt below zero for the longest stretch on record. Bond prices are so high in Japan almost two-thirds of its government debt have negative yields.

And at a time when teetering financial markets have made security a paramount concern, investors are discovering there are few good options left. Even in the U.S., long the destination of choice in times of duress, Treasuries are in such demand that when their cash flows are converted into euros, yields are even worse than the scant returns on German bunds.

“It’s tough at these levels, but at the moment there seem to be few alternatives,” said Kind, the head of asset allocation at Frankfurt Trust, which oversees about $20 billion. “This is quite a tricky situation. The risk of a selloff in safe-haven assets has increased” as yields get lower and lower.

Despite those reservations, Kind has bought negative-yielding bonds in recent weeks. It’s a response to the extraordinary steps by the likes of the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan to push interest rates below zero and buy more government bonds as they try to jump-start their economies.

This chart shows the percentage of countries whose two-year generic bond yields fall within certain ranges. The dark gray shows that about 34 percent of the 47 countries included had negative yields as of the end of January.

But that’s not all. The willingness of debt investors to effectively pay governments to borrow also reflects increasing skepticism of central bank policies -- and concern those very measures may ultimately do more harm to the global economy than good. Even after central banks around the world spent trillions since the financial crisis on quantitative easing and dropped policy rates below zero for about two dozen countries, the market’s outlook for inflation globally is closing in on post-crisis lows.

While the trade-off of losing a little money for the security of owning government debt when things seem so gloomy might be a small one for conservative investors, there are considerable risks in the mean time.

Last year, fears of deflation and the ECB’s introduction of QE pushed the average yield on euro-area debt to a record-low 0.475 percent and sent those on German bunds toward zero. Then, in the months that followed, faint glimmers of optimism over the outlook the region’s economy helped spark a sudden and violent reversal that caused yields to soar.

By the middle of June, yields on longer-term German debt jumped more than a percentage point and left investors with an unprecedented 13 percent loss in the quarter, index data compiled by Bank of America Corp. show.

Nevertheless, as worries over the economic health of China and the U.S. -- the world’s two main engines of growth -- continue to linger, volatility spreads throughout financial markets and investors question the wisdom of negative rates, government bonds with ultra-low yields remain in demand.

This month, yields on Germany’s two-year notes touched a record-low minus 0.557 percent. The average yield on 1.06 trillion euros of German debt is currently minus 0.05 percent and has been negative every day for two weeks, according to Bank of America. In Japan, yields on about $4.5 trillion of government debt are less than zero, index data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Just last week, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development cut its 2016 global growth forecast to 3 percent from 3.3 percent in November, saying that “financial stability risks are substantial.”

A majority of economists in a Bloomberg survey also say negative rates will be in place at the ECB until at least the first quarter of 2018 and at the BOJ until at least the end of that year.

Benchmark bond yields in G-7 have all fallen below 2%

“Risk-free now now has a cost” and clients are learning that they should accept it, said Mauro Vittorangeli, a senior fixed-income money manager at Allianz Global Investors, which manages about $505 billion.

And it’s not like debt investors are spoiled for choice. Benchmark 10-year notes in every G-7 nation yield less than 2 percent. Even U.S. Treasuries, “the least ugly duck out there,” according to Amundi’s David Ric, now yield 1.74 percent after tumbling by about a half-percentage point this year.

Many investors, especially at the start of the year, were looking for “something liquid and something that has value,” said Ric, the London-based head of absolute-return fixed-income strategies at Amundi, which oversees more than $1 trillion. “So Treasuries looked reasonable from that perspective because they offer a decent yield.”

Still, the traditional yield advantage that U.S. debt has enjoyed over sovereign bonds in Europe and Japan isn’t so clear anymore.

For euro-based buyers of 10-year Treasuries, swapping the dollar interest payments into euros over the life the security lowers the yield to 0.12 percent, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, which uses a cross-currency yield analysis based on future expectations for interest rates and foreign exchange. That’s less than the 0.2 percent yield on German 10-year bunds.

For Japanese buyers, it’s even worse. The same process results in a minus 0.68 percent yield in yen.

The effect is already playing out this month. While Treasuries have returned 1 percent in February, that translates into a loss of 1.6 percent in euros, Bank of America data show. In yen, the loss balloons to 5.9 percent. What’s more, hedging all the currency risk results in a return for euro buyers that’s no better than just investing in German bunds.

Part of the reason the comparative advantage has diminished has to do with the yield-starved investors in Europe and Japan themselves, who poured into U.S. debt over the past year to try and eke out bigger returns.

The worsening U.S. outlook is also driving more investors into the safety of Treasuries. Traders have all but abandoned expectations the Federal Reserve will raise interest rates this year. While Fed officials have said any discussion of negative rates was premature, Chair Janet Yellen noted in Congressional testimony that the central bank was taking another look at negative rates as a potential tool if the economy faltered.

Yet regardless of where debt investors turn for shelter, what’s becoming increasingly clear that they’re going to ever greater lengths for that security.

“We are in a totally new world,” said Allianz’s Vittorangeli.

bloomberg.com |