The Sub-Zero Club: Getting Used to the Upside-Down World Economy

In the new reality of negative rates, borrowers get paid and savers get penalized

by Simon Kennedy

April 19, 2016 — 12:01 AM EDT

Japanese families seem to have a sudden affinity for home safes. According to the Tokyo-based manufacturer Eiko, shipments have doubled since last fall. And in Germany, insurer Munich Re has stashed some 10 million euros ($11.4 million) worth of its own cash into vaults.Why the squirreling? One possible reason is the creeping imposition of negative interest rates across the world, which could make it more rewarding to bypass banks—and a safe or vault is, well, more secure than a mattress.

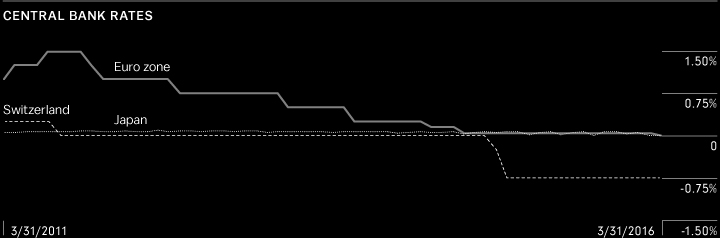

Welcome to the upside-down world of modern monetary policy. In this new reality, borrowers get paid and savers penalized. Almost 500 million people in a quarter of the global economy now live in countries where interest rates measure less than zero.That would’ve been an almost unthinkable phenomenon before the 2008 financial crisis, and one major economies didn’t seriously consider until two years ago, when the European Central Bank first partook in the experiment. Now the ECB and the Bank of Japan are diving deeper into the sub-zero world as they seek more ways to spark inflation.

ECB President Mario Draghi currently charges 0.4 percent on the euros deposited by banks in his coffers overnight. BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, whose country knows more than most about the perils of soft inflation, knocked his benchmark down to an unprecedented -0.1 percent in January. Their counterparts in Sweden, Switzerland, and Denmark have already been running negative campaigns for a while now. The U.S. Federal Reserve has, so far, remained on the sidelines.

The overall aim, of course, is to spur banks to look elsewhere when lending their cash, preferably to spenders such as companies and consumers, who should also benefit from low borrowing costs in markets. There’s also the hope—especially in Scandinavia and Switzerland—that currencies will fall as investors seek higher returns elsewhere, lifting exports and import costs.

The policy isn’t without risks. Bank profits could be squeezed, money markets may freeze, and consumers could end up with bulging mattresses to avoid paying to keep money in a bank account. The whole effort could wind up leaving inflation even weaker—hence the tiptoe approach to cutting rates.

I’m skeptical about the efficacy of negative interest rates,” says Barry Eichengreen, professor of economics at University of California at Berkeley. “They increase the cost of doing business for the banks, which find it hard to pass on those costs to borrowers, given the weakness of the economy and hence of loan demand. Weaker bank balance sheets are not ideal from the standpoint of jump-starting growth, to put an understated gloss on the point.”

Financial markets are already feeling the effect. Bonds worth about $8 billion now offer yields below zero. Japan paid investors to buy 10-year debt this year for the first time, while Siemens and Royal Dutch Shell are among companies that have seen their yields sink into negative territory.

If the central bankers’ audacious plan works, inflation would accelerate from the 1.1 percent rate the International Monetary Fund forecasts for developed markets this year, which is barely half the 2 percent most authorities view as ensuring price stability. The problem: Not everyone is enamored of the new approach. Investors who once cheered fresh doses of easy money by sending stocks to record highs responded to this year’s negative campaigns by dumping equities. Spooked by a slowdown in China at the same time central banks dug deeper, traders wiped about $2 trillion from the value of global stocks through April 1, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Among the reasons was the fear that even lower rates would erode already strained profits at banks by compressing the gap between the cost of funding and the revenue from lending at a time when lenders are already under stress. In 2015, Deutsche Bank experienced its first annual loss since 2008, while analysts at Goldman Sachs reckon that banks heavily reliant on deposits will see an earnings-per-share impact of as much as 10 percent for each cut of 10 basis points. “Margins are going to be squeezed, so banks have to find ways to go around these negative rates,” says Lorenzo Bini Smaghi, Société Générale’s chairman and a former ECB policymaker.

At UBS, Chairman Axel Weber, also a former ECB official, says the challenge is that demand for loans is lacking no matter how affordable they are. Lending to euro area nonfinancial companies and consumers, excluding mortgages, has been stuck at about 6.8 trillion euros since June 2014, according to the ECB. Pension and insurance funds, which may struggle to secure returns for clients when yields are so low, are also likely losers. London-based hedge fund Algebris Investments is opening a fund to help such asset managers.

A more existential worry is that by embracing a policy they once declined to countenance, central bankers are signaling they’re finally running low on ammunition. Such an admission would suggest the tepid economic growth of recent years is beyond their control—and perhaps a permanent state of affairs.

“It seems that financial markets increasingly view these experimental moves as desperate and consequently damaging to financial and economic stability,” Scott Mather, a managing director at Pacific Investment Management Co., told clients in February. “They have not been as effective as they seem.”

Even some fellow policymakers cast doubt on the initiative. Bank of England Governor Mark Carney warned that a deeper dive risked stealing demand from abroad—code for a “currency war.” The central bankers behind the cuts are aware of the criticism. When Draghi, who pared his deposit rate in December, did so again in March, he suggested he would go no lower and said a new round of loans to banks would include a sweetener for those who pass the money on to consumers or businesses. Kuroda also held off cutting further in March.

That’s not to say Draghi and Kuroda will remain hands-off. Economists at Morgan Stanley predict further reductions from both the ECB and BOJ this year, while those at JPMorgan Chase say that if the authorities subject only a portion of reserves for negative rates—as Japan already does—then the ECB could cut to -4.5 percent and the BOJ -3.45 percent.

The ECB argues that negative rates have helped banks lower their funding costs, generated capital gains on bond holdings, and reduced bad loans. Draghi says he’s striking the right balance. “The aggregate profitability of the banking system has not been hindered by the experience we had of negative rates,” he said in March. “Does it mean that we can go as negative as we want without having any consequence on the banking system? The answer is no.”

The central bankers also draw strength from the experience of others. Danish central bank Governor Lars Rohde notes that 2015 was the most profitable year for his country’s banks since 2008, despite a deposit rate of less than zero. Former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke also said in a recent blog post that negative rates “appear to have both modest benefits and manageable costs,” and that market anxiety over below-zero borrowing costs “seems to me to be overdone.”

That doesn’t mean the Fed will be plumbing new depths anytime soon. The recent pickup in prices leaves Fed Chair Janet Yellen and colleagues debating when next to repeat December’s rate hike. Yellen nevertheless said recently that her central bank was taking a look at sub-zero life “in the event that we needed to add accommodation,” while Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer acknowledged that the approach is “working more than I can say I expected in 2012.”

Central banks may be forced to shelve the policy for good if banks pass the cost of negative rates on to consumers, who in turn pull their money out or, worse, stage a bank run. More than three quarters of depositors would remove their funds if negative rates were imposed on savings accounts, according to a global survey of 13,000 consumers by ING. Yet even then, there may be workaround. In calling for the end of the 500 euro note to thwart tax evasion and terrorism financing, Draghi also knows scrapping the denomination would make it harder to just sit on cash. BOE policymaker Andrew Haldane and former IMF chief economist Kenneth Rogoff are among those predicting “cashless” societies, which would also increase the potency of central banks running negative rates.

The upshot: Now that they’ve tried the tool, central banks are likely to put it to use. Where once they assumed the “zero lower bound,” as it’s known in technical jargon, was as low as they could go, now they know better. Says Gabriel Stein, an economist at Oxford Economics, “Negative rates are here to stay

------------------------------------------

(editorial observation by JJP..... I really doubt that negative rates are here to stay...... hence Gold and silver and Precious metals as a competing currency... China just launched their own daily fixing of the price of Gold, in the past day or so )

bloomberg.com |

|