yeah, ignore the elephant

+++

US War Crimes or ‘Normalized Deviance’

August 15, 2016

The U.S. foreign policy establishment and its mainstream media operate with a pervasive set of hypocritical standards that justify war crimes — or what might be called a “normalization of deviance,” writes Nicolas J S Davies.

By Nicolas J S Davies

Sociologist Diane Vaughan coined the term “normalization of deviance ” as she was investigating the explosion of the Challenger space shuttle in 1986. She used it to describe how the social culture at NASA fostered a disregard for rigorous, physics-based safety standards, effectively creating new, lower de facto standards that came to govern actual NASA operations and led to catastrophic and deadly failures.

Vaughan published her findings in her prize-winning book, The Challenger Launch Decision: Risky Technology, Culture and Deviance at NASA, which, in her words, “shows how mistake, mishap, and disaster are socially organized and systematically produced by social structures” and “shifts our attention from individual causal explanations to the structure of power and the power of structure and culture – factors that are difficult to identify and untangle yet have great impact on decision making in organizations.”

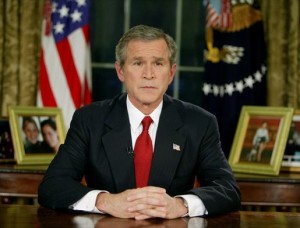

President George W. Bush announcing the start of his invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003. President George W. Bush announcing the start of his invasion of Iraq on March 19, 2003.

When the same pattern of organizational culture and behavior at NASA persisted until the loss of a second shuttle in 2003, Diane Vaughan was appointed to NASA’s accident investigation board, which belatedly embraced her conclusion that the “normalization of deviance” was a critical factor in these catastrophic failures.

The normalization of deviance has since been cited in a wide range of corporate crimes and institutional failures, from Volkswagen’s rigging of emissions tests to deadly medical mistakes in hospitals. In fact, the normalization of deviance is an ever-present danger in most of the complex institutions that govern the world we live in today, not least in the bureaucracy that formulates and conducts U.S. foreign policy.

The normalization of deviance from the rules and standards that formally govern U.S. foreign policy has been quite radical. And yet, as in other cases, this has gradually been accepted as a normal state of affairs, first within the corridors of power, then by the corporate media and eventually by much of the public at large.

Once deviance has been culturally normalized, as Vaughan found in the shuttle program at NASA, there is no longer any effective check on actions that deviate radically from formal or established standards – in the case of U.S. foreign policy, that would refer to the rules and customs of international law, the checks and balances of our constitutional political system and the experience and evolving practice of generations of statesmen and diplomats.

Normalizing the Abnormal

It is in the nature of complex institutions infected by the normalization of deviance that insiders are incentivized to downplay potential problems and to avoid precipitating a reassessment based on previously established standards. Once rules have been breached, decision-makers face a cognitive and ethical conundrum whenever the same issue arises again: they can no longer admit that an action will violate responsible standards without admitting that they have already violated them in the past.

This is not just a matter of avoiding public embarrassment and political or criminal accountability, but a real instance of collective cognitive dissonance among people who have genuinely, although often self-servingly, embraced a deviant culture. Diane Vaughan has compared the normalization of deviance to an elastic waistband that keeps on stretching.

At the start of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, President George W. Bush ordered the U.S. military to conduct a devastating aerial assault on Baghdad, known as “shock and awe.” At the start of the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, President George W. Bush ordered the U.S. military to conduct a devastating aerial assault on Baghdad, known as “shock and awe.”

Within the high priesthood that now manages U.S. foreign policy, advancement and success are based on conformity with this elastic culture of normalized deviance. Whistle-blowers are punished or even prosecuted, and people who question the prevailing deviant culture are routinely and efficiently marginalized, not promoted to decision-making positions.

For example, once U.S. officials had accepted the Orwellian “doublethink” that “targeted killings,” or “manhunts” as Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld called them, do not violate long-standing prohibitions aga inst assassination, even a new administration could not walk that decision back without forcing a deviant culture to confront the wrong-headedness and illegality of its original decision.

Then, once the Obama administration had massively escalat ed the CIA’s drone program as an alternative to kidnapping and indefinite detention at Guantanamo, it became even harder to acknowledge that this is a policy of cold-blooded murder that provokes widespread anger and hostility and is counter-productive to legitimate counterterrorism goals – or to admit that it violates the U.N. Charter’s prohibition on the use of force, as U.N. special rapporteurs on extrajudicial killings have warned.

Underlying such decisions is the role of U.S. government lawyers who provide legal cover for them, but who are themselves shielded from accountability by U.S. non-recognition of international courts and the extraordinary deference of U.S. courts to the Executive Branch on matters of “national security.” These lawyers enjoy a privilege that is unique in their profession, issuing legal opinions that they will never have to defend before impartial courts to provide legal fig-leaves for war crimes.

The deviant U.S. foreign policy bureaucracy has branded the formal rules that are supposed to govern our country’s international behavior as “obsolete” and “quaint”, as a White House lawyer wrote in 2004. And yet these are the very rules that past U.S. leaders deemed so vital that they enshrined them in constitutionally binding international treaties and U.S. law.

Let’s take a brief look at how the normalization of deviance undermines two of the most critical standards that formally define and legitimize U.S. foreign policy: the U.N. Charter and the Geneva Conventions.

The United Nations Charter

In 1945, after two world wars killed 100 million people and left much of the world in ruins, the world’s governments were shocked into a moment of sanity in which they agreed to settle future international disputes peacefully. The U.N. Charter therefore prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at a press conference. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at a press conference.

As President Franklin Roosevelt told a joint session of Congress on his return from the Yalta conference, this new “permanent structure of peace … should spell the end of the system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balance of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries – and have always failed.”

The U.N. Charter’s prohibition against the threat or use of force codifies the long-standing prohibition of aggression in English common law and customary international law, and reinforces the renunciation of war as an instrument of national policy in the 1928 Kellogg Briand Pact. The judges at Nuremberg ruled that, even before the U.N. Charter came into effect, aggression was already the “supreme international crime.”

No U.S. leader has proposed abolishing or amending the U.N. Charter to permit aggression by the U.S. or any other country. And yet the U.S. is currently conducting ground operations, air strikes or drone strikes in at least seven countries: Afghanistan; Pakistan; Iraq; Syria; Yemen; Somalia; and Libya. U.S. “special operations forces” conduct secret operations in a hundred more. U.S. leaders still openly threaten Iran, despite a diplomatic breakthrough that was supposed to peacefully settle bilateral differences.

President-in-waiting Hillary Clinton still believes in backing U.S. demands on other countries with illegal threats of force, even though every threat she has backed in the past has only served to create a pretext for war, from Yugoslavia to Iraq to Libya. But the U.N. Charter prohibits the threat as well as the use of force precisely because the one so regularly leads to the other.

The only justifications for the use of force permitted under the U.N. Charter are proportionate and necessary self-defense or an emergency request by the U.N. Security Council for military action “to restore peace and security.” But no other country has attacked the United States, nor has the Security Council asked the U.S. to bomb or invade any of the countries where we are now at war.

The wars we have launched since 2001 have killed about 2 million people, of whom nearly all were completely innocent of involvement in the crimes of 9/11. Instead of “restoring peace and security,” U.S. wars have only plunged country after country into unending violence and chaos.

Like the specifications ignored by the engineers at NASA, the U.N. Charter is still in force, in black and white, for anyone in the world to read. But the normalization of deviance has replaced its nominally binding rules with looser, vaguer ones that the world’s governments and people have neither debated, negotiated nor agreed to.

In this case, the formal rules being ignored are the ones that were designed to provide a viable framework for the survival of human civilization in the face of the existential threat of modern weapons and warfare – surely the last rules on Earth that should have been quietly swept under a rug in the State Department basement.

The Geneva Conventions

Courts martial and investigations by officials and human rights groups have exposed “rules of engagement” issued to U.S. forces that flagrantly violate the Geneva Conventions and the protections they provide to wounded combatants, prisoners of war and civilians in war-torn countries:

Some of the original detainees jailed at the Guantanamo Bay prison, as put on display by the U.S. military. Some of the original detainees jailed at the Guantanamo Bay prison, as put on display by the U.S. military.

–The Command’s Responsibility report by Human Rights First examined 98 deaths in U.S. custody in Iraq and Afghanistan. It revealed a deviant culture in which senior officials abused their authority to block investigations and guarantee their own impunity for murders and torture deaths that U.S. law defines as capital crimes.

Although torture was authorized from the very top of the chain of command, the most senior officer charged with a crime was a Major and the harshest sentence handed down was a five-month prison sentence.

–U.S. rules of engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan have included: systematic, theater-wide use of torture; orders to “dead-check” or kill wounded enemy combatants; orders to “kill all military-age males” during certain operations; and “weapons-free” zones that mirror Vietnam-era “free-fire” zones.

A U.S. Marine corporal told a court martial that “Marines consider all Iraqi men part of the insurgency”, nullifying the critical distinction between combatants and civilians that is the very basis of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

When junior officers or enlisted troops have been charged with war crimes, they have been exonerated or given light sentences because courts have found that they were acting on orders from more senior officers. But the senior officers implicated in these crimes have been allowed to testify in secret or not to appear in court at all, and no senior officer has been convicted of a war crime.

–For the past year, U.S. forces bombing Iraq and Syria have operated under loosened rules of engagement that allow the in-theater commander General McFarland to approve bomb- and missile-strikes that are expected to kill up to 10 civilians each.

But Kate Clark of the Afghanistan Analysts Network has documented that U.S. rules of engagement already permit routine targeting of civilians based only on cell-phone records or “guilt by proximity” to other people targeted for assassination. The Bureau of Investigative Journalism has determined that only 4 percent of thousands of drone victims in Pakistan have been positively identified as Al Qaeda members, the nominal targets of the CIA’s drone campaign.

–Amnesty International’s 2014 report Left In The Dark documented a complete lack of accountability for the killing of civilians by U.S. forces in Afghanistan since President Obama’s escalation of the war in 2009 unleashed thousands more air strikes and special forces night raids.

Nobody was charged over the Ghazi Khan raid in Kunar province on Dec. 26, 2009, in which U.S. special forces summarily executed at least seven children, including four who were only 11 or 12 years old.

More recently, U.S. forces attacked a Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, killing 42 doctors, staff and patients, but this flagrant violation of Article 18 of the Fourth Geneva Convention did not lead to criminal charges either.

Although the U.S. government would not dare to formally renounce the Geneva Conventions, the normalization of deviance has effectively replaced them with elastic standards of behavior and accountability whose main purpose is to shield senior U.S. military officers and civilian officials from accountability for war crimes.

The Cold War and Its Aftermath

The normalization of deviance in U.S. foreign policy is a byproduct of the disproportionate economic, diplomatic and military power of the United States since 1945. No other country could have got away with such flagrant and systematic violations of international law.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, at his headquarters in the European theater of operations. He wears the five-star cluster of the newly-created rank of General of the Army. Feb. 1, 1945. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander, at his headquarters in the European theater of operations. He wears the five-star cluster of the newly-created rank of General of the Army. Feb. 1, 1945.

But in the early days of the Cold War, America’s World War II leaders rejected calls to exploit their new-found power and temporary monopoly on nuclear weapons to unleash an aggressive war against the U.S.S.R.

General Dwight Eisenhower gave a speech in St. Louis in 1947 in which he warned, “Those who measure security solely in terms of offensive capacity distort its meaning and mislead those who pay them heed. No modern nation has ever equaled the crushing offensive power attained by the German war machine in 1939. No modern nation was broken and smashed as was Germany six years later.”

But, as Eisenhower later warned, the Cold War soon gave rise to a “military-industrial complex” that may be the case par excellence of a highly complex tangle of institutions whose social culture is supremely prone to the normalization of deviance. Privately, Eisenhower lamented, “God help this country when someone sits in this chair who doesn’t know the military as well as I do.”

That describes everyone who has sat in that chair and tried to manage the U.S. military-industrial complex since 1961, involving critical decisions on war and peace and an ever -growing military budget. Advising the President on these matters are the Vice President, the Secretaries of State and Defense, the Director of National Intelligence, several generals and admirals and the chairs of powerful Congressional committees. Nearly all these officials’ careers represent some version of the “revolving door” between the military and “intelligence” bureaucracy, the executive and legislative branches of government, and top jobs with military contractors and lobbying firms.

Each of the close advisers who have the President’s ear on these most critical issues is in turn advised by others who are just as deeply embedded in the military-industrial complex, from think-tanks funded by weapons manufacturers to Members of Congress with military bases or missile plants in their districts to journalists and commentators who market fear, war and militarism to the public.

With the rise of sanctions and financial warfare as a tool of U.S. power, Wall Street and the Treasury and Commerce Departments are also increasingly entangled in this web of military-industrial interests.

The incentives driving the creeping, gradual normalization of deviance throughout the ever-growing U.S. military-industrial complex have been powerful and mutually reinforcing for over 70 years, exactly as Eisenhower warned.

Richard Barnet explored the deviant culture of Vietnam-era U.S. war leaders in his 1972 book Roots Of War. But there are particular reasons why the normalization of deviance in U.S. foreign policy has become even more dangerous since the end of the Cold War.

In the aftermath of World War II, the U.S. and U.K. installed allied governments in Western and Southern Europe, restored Western colonies in Asia and militarily occupied South Korea. The divisions of Korea and Vietnam into north and south were justified as temporary, but the governments in the south were U.S. creations imposed to prevent reunification under governments allied with the U.S.S.R. or China. U.S. wars in Korea and Vietnam were then justified, legally and politically, as military assistance to allied governments fighting wars of self-defense.

The U.S. role in anti-democratic coups in Iran, Guatemala, the Congo, Brazil, Indonesia, Ghana, Chile and other countries was veiled behind thick layers of secrecy and propaganda. A veneer of legitimacy was still considered vital to U.S. policy, even as a culture of deviance was being normalized and institutionalized beneath the surface.

The Reagan Years

It was not until the 1980s that the U.S. ran seriously afoul of the post-1945 international legal framework it had helped to build. When the U.S. set out to destroy the revolutionary Sandinista government of Nicaragua by mining its harbors and dispatching a mercenary army to terrorize its people, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) convicted the U.S. of aggression and ordered it to pay war reparations.

President Reagan meets with Vice President George H.W. Bush on Feb. 9, 1981. (Photo credit: Reagan Presidential Library.) President Reagan meets with Vice President George H.W. Bush on Feb. 9, 1981. (Photo credit: Reagan Presidential Library.)

The U.S. response revealed how far the normalization of deviance had already taken hold of its foreign policy. Instead of accepting and complying with the court’s ruling, the U.S. announced its withdrawal from the binding jurisdiction of the ICJ.

When Nicaragua asked the U.N. Security Council to enforce the payment of reparations ordered by the court, the U.S. abused its position as a Permanent Member of the Security Council to veto the resolution. Since the 1980s, the U.S. has vetoed twice as many Security Council resolutions as the other Permanent Members combined, and the U.N. General Assembly passed resolutions condemning the U.S. invasions of Grenada (by 108 to 9) and Panama (by 75 to 20), calling the latter “a flagrant violation of international law.”

President George H.W. Bush and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher obtained U.N. authorization for the First Gulf War and resisted calls to launch a war of regime change against Iraq in violation of their U.N. mandate. Their forces massacred Iraqi forces fleeing Kuwait, and a U.N. report described how the “near apocalyptic” U.S.-led bombardment of Iraq reduced what “had been until January a rather highly urbanized and mechanized society” to “a pre-industrial age nation.”

But new voices began to ask why the U.S. should not exploit its unchallenged post-Cold War military superiority to use force with even less restraint. During the Bush-Clinton transition, Madeleine Albright confronted General Colin Powell over his “Powell doctrine” of limited war, protesting, “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?”

Public hopes for a “peace dividend” were ultimately trumped by a “power dividend” sought by military-industrial interests. The neoconservatives of the Project for the New American Century led the push for war on Iraq, while “humanitarian interventionists” now use the “soft power” of propaganda to selectively identify and demonize targets for U.S.-led regime change and then justify war under the “responsibility to protect” or other pretexts. U.S. allies (NATO, Israel, the Arab monarchies et al) are exempt from such campaigns, safe within what Amnesty International has labeled an “accountability-free zone.”

Madeleine Albright and her colleagues branded Slobodan Milosevic a “new Hitler” for trying to hold Yugoslavia together, even as they ratcheted up their own genocidal sanctions against Iraq. Ten years after Milosevic died in prison at the Hague, he was posthumously exonerated by an international court.

In 1999, when U.K. Foreign Secretary Robin Cook told Secretary of State Albright the British government was having trouble “with its lawyers” over NATO plans to attack Yugoslavia without U.N. authorization, Albright told him he should “get new lawyers.”

By the time mass murder struck New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, the normalization of deviance was so firmly rooted in the corridors of power that voices of peace and reason were utterly marginalized.

Former Nuremberg prosecutor Ben Ferencz told NPR eight days later, “It is never a legitimate response to punish people who are not responsible for the wrong done. … We must make a distinction between punishing the guilty and punishing others. If you simply retaliate en masse by bombing Afghanistan, let us say, or the Taliban, you will kill many people who don’t approve of what has happened.”

But from the day of the crime, the war machine was in motion, targeting Iraq as well as Afghanistan.

The normalization of deviance that promoted war and marginalized reason at that moment of national crisis was not limited to Dick Cheney and his torture-happy acolytes, and so the global war they unleashed in 2001 is still spinning out of control.

When President Obama was elected in 2008 and awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, few people understood how many of the people and interests shaping his policies were the same people and interests who had shaped President George W. Bush’s, nor how deeply they were all steeped in the same deviant culture that had unleashed war, systematic war crimes and intractable violence and chaos upon the world.

A Sociopathic Culture

Until the American public, our political representatives and our neighbors around the world can come to grips with the normalization of deviance that is corrupting the conduct of U.S. foreign policy, the existential threats of nuclear war and escalating conventional war will persist and spread.

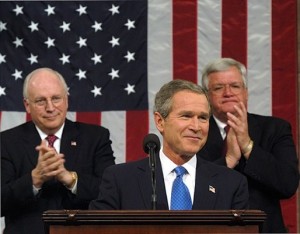

President George W. Bush pauses for applause during his State of the Union Address on Jan. 28, 2003, when he made a fraudulent case for invading Iraq. Seated behind him are Vice President Dick Cheney and House Speaker Dennis Hastert. (White House photo) President George W. Bush pauses for applause during his State of the Union Address on Jan. 28, 2003, when he made a fraudulent case for invading Iraq. Seated behind him are Vice President Dick Cheney and House Speaker Dennis Hastert. (White House photo)

This deviant culture is sociopathic in its disregard for the value of human life and for the survival of human life on Earth. The only thing “normal” about it is that it pervades the powerful, entangled institutions that control U.S. foreign policy, rendering them impervious to reason, public accountability or even catastrophic failure.

The normalization of deviance in U.S. foreign policy is driving a self-fulfilling reduction of our miraculous multicultural world to a “battlefield” or testing-ground for the latest U.S. weapons and geopolitical strategies. There is not yet any countervailing movement powerful or united enough to restore reason, humanity or the rule of law, domestically or internationally, although new political movements in many countries offer viable alternatives to the path we are on.

As the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists warned when it advanced the hands of the Doomsday Clock to 3 minutes to midnight in 2015, we are living at one of the most dangerous times in human history. The normalization of deviance in U.S. foreign policy lies at the very heart of our predicament.

Nicolas J S Davies is the author of Blood On Our Hands: the American Invasion and Destruction of Iraq. He also wrote the chapters on “Obama at War” in Grading the 44th President: a Report Card on Barack Obama’s First Term as a Progressive Leader. |