| | 17 New (2017) Scientific Papers Affirm Today’s Warming Is Not Global, Unprecedented, Or RemarkableBy Kenneth Richard on 26. January 2017

The Hockey Stick Collapses (2017)A collection of 60 peer-reviewed scientific papers published in 2016 were displayed here last month in an article entitled, “ The Hockey Stick Collapses: 60 New (2016) Scientific Papers Affirm Today’s Warming Isn’t Global, Unprecedented, Or Remarkable“.

Each paper from the 2016 collection cast doubt on claims of an especially unusual global-scale warming during modern times.

Yes, some regions of the Earth have been warming in recent decades (i.e., the Arctic since the 1990s), or at some point in the last 100 years. Some regions have been cooling for decades at a time (i.e., the Arctic during the 1950s to 1980s, the Southern Ocean since 1979). And many regions have shown no significant net changes or trends in either direction relative to the last few hundred to thousands of years.

In other words, there is nothing historically unprecedented or remarkable about today’s climate when viewed in the context of natural variability.

And the scientific evidence continues to accumulate for 2017. In just the first month of this year, there have already been at least 17 papers published in scientific journals once again documenting that modern warming is not global, unprecedented, or remarkable. In fact, several of these papers indicate that we are still living through some of the coldest temperatures of the last 10,000 years (just above Little Ice Age levels), and that a large portion of the amplitude of the modern warming trend (if there is one depicted) was realized prior to the mid-20th century, or before the period when human CO2 emissions began to rise dramatically.

Needless to say, these papers do not support the position that human CO2 emissions are the primary drivers of climate.

Köse et al., 2017 (Turkey, Europe)“The reconstruction is punctuated by a temperature increase during the 20th century; yet extreme cold and warm events during the 19th century seem to eclipse conditions during the 20th century. We found significant correlations between our March–April spring temperature reconstruction and existing gridded spring temperature reconstructions for Europe over Turkey and southeastern Europe. … During the last 200 years, our reconstruction suggests that the coldest year was 1898 and the warmest year was 1873. The reconstructed extreme events also coincided with accounts from historical records. … Further, the warming trends seen in our record agrees with data presented by Turkes and Sumer (2004), of which they attributed [20th century warming] to increased urbanization in Turkey. Considering long-term changes in spring temperatures, the 19th century was characterized by more high-frequency fluctuations compared to the 20th century, which was defined by more gradual changes and includes the beginning of decreased DTRs [diurnal temperature ranges] in the region (Turkes and Sumer, 2004).”

Flannery et al., 2017 (Florida, U.S.)“The early part of the reconstruction (1733–1850) coincides with the end of the Little Ice Age, and exhibits 3 of the 4 coolest decadal excursions in the record. However, the mean SST estimate from that interval during the LIA is not significantly different from the late 20th Century SST mean. The most prominent cooling event in the 20th Century is a decade centered around 1965. This corresponds to a basin-wide cooling in the North Atlantic and cool phase of the AMO.”

Mayewski et al., 2017 (Antarctic Circle)

Rydval et al., 2017 (Scotland, Scandinavia, Northern Europe, Alps, France-Spain)“[T]he recent summer-time warming in Scotland is likely not unique when compared to multi-decadal warm periods observed in the 1300s, 1500s, and 1730s … All six [Northern Hemisphere] records show a warmer interval in the period leading up to the 1950s, although it is less distinct in the CEU reconstruction. [E]xtreme cold (and warm) years observed in NCAIRN appear more related to internal forcing of the summer North Atlantic Oscillation. … There is reasonable agreement in general between the records regarding protracted cold periods which occur during the LIA and specifically around the Maunder solar minimum centred on the second half of the seventeenth century and to some extent also around the latter part of the fifteenth century coinciding with part of the Spörer minimum (Usoskin et al. 2007).”

Reynolds et al., 2017 (North Atlantic, Central England)

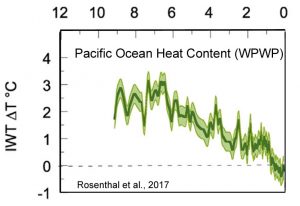

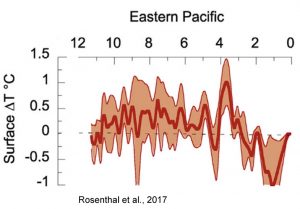

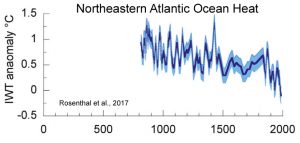

Rosenthal et al., 2017 (Atlantic, Pacific Oceans)“Here we review proxy records of intermediate water temperatures from sediment cores and corals in the equatorial Pacific and northeastern Atlantic Oceans, spanning 10,000 years beyond the instrumental record. These records suggests that intermediate waters [0-700 m] were 1.5-2°C warmer during the Holocene Thermal Maximum than in the last century. Intermediate water masses cooled by 0.9°C from the Medieval Climate Anomaly to the Little Ice Age. These changes are significantly larger than the temperature anomalies documented in the instrumental record. The implied large perturbations in OHC and Earth’s energy budget are at odds with very small radiative forcing anomalies throughout the Holocene and Common Era. … The records suggest that dynamic processes provide an efficient mechanism to amplify small changes in insolation [surface solar radiation] into relatively large changes in OHC.”

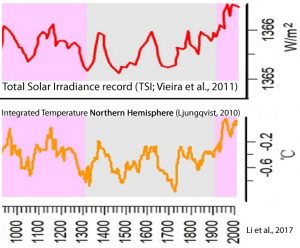

Li et al., 2017 (North China, Northern Hemisphere)“We suggest that solar activity may play a key role in driving the climatic fluctuations in NC [North China] during the last 22 centuries, with its quasi ~100, 50, 23, or 22-year periodicity clearly identified in our climatic reconstructions. … It has been widely suggested from both climate modeling and observation data that solar activity plays a key role in driving late Holocene climatic fluctuations by triggering global temperature variability and atmospheric dynamical circulation“

Kawahata et al., 2017 (Northern Japan)“The SST [sea surface temperature] shows a broad maximum (~17.3 °C) in the mid-Holocene (5-7 cal kyr BP), which corresponds to the Jomon transgression. … The SST maximum continued for only a century and then the SST [sea surface temperatures] dropped by 3.5 °C [15.1 to 11.6 °C] within two centuries. Several peaks fluctuate by 2°C over a few centuries.”

Saini et al., 2017 (Tibetan Plateau)

Dechnik et al., 2017 (Tropical Western Pacific)“[I]t is generally accepted that relative sea level reached a maximum of 1–1.5 m above present mean sea level (pmsl) by ~7 ka [7,000 years ago] (Lewis et al., 2013)”

Wu et al., 2017 (South China Sea)“The alkenone-based SST reconstruction shows rapid warming in the first 1500 years of the Holocene … an increase of sea surface temperature from c. 23.0 °C to 27.0 °C, associated with a strengthened summer monsoon from c. 10,350 to 8900 cal. years BP. This was also a period of rapid sea-level rise and marine transgression, during which the sea inundated the palaeo-incised channel … In these 1500 years, fluvial discharge was strong and concentrated within the channel, and the high sedimentation rate (11.8 mm/yr [1.18 m per century]) was very close to the rate of sea-level rise.”

Sun et al., 2017 (China, Southwest)“[A]t least six centennial droughts occurred at about 7300, 6300, 5500, 3400, 2500 and 500 cal yr BP. Our findings are generally consistent with other records from the ISM [Indian Summer Monsoon] region, and suggest that the monsoon intensity is primarily controlled by solar irradiance on a centennial time scale. This external forcing may have been amplified by cooling events in the North Atlantic and by ENSO activity in the eastern tropical Pacific, which shifted the ITCZ further southwards. The inconsistency between local rainfall amount in the southeastern margin of the QTP and ISM intensity may also have been the result of the effect of solar activity on the local hydrological cycle on the periphery of the plateau.”

Wu et al., 2017 (Costa Rica)“The existence of depressed MAAT [mean annual temperatures] (1.3°C lower than the 3200-year average) between 1480 CE and 1860 CE (470–90 cal. yr BP) may reflect the manifestation of the ‘Little Ice Age’ (LIA) in southern Costa Rica. Evidence of low-latitude cooling and drought during the ‘LIA’ has been documented at several sites in the circum-Caribbean and from the tropical Andes, where ice cores suggest marked cooling between 1400 CE and 1900 CE. Lake and marine records recovered from study sites in the southern hemisphere also indicate the occurrence of ‘LIA’ cooling. High atmospheric aerosol concentrations, resulting from several large volcanic eruptions and sea-ice/ocean feedbacks, have been implicated as the drivers responsible for the ‘LIA’.”

Park, 2017 (Western Tropical Pacific)“Late Holocene climate change in coastal East Asia was likely driven by ENSO variation. Our tree pollen index of warmness (TPIW) shows important late Holocene cold events associated with low sunspot periods such as Oort, Wolf, Spörer, and Maunder Minimum. Comparisons among standard Z-scores of filtered TPIW, ?TSI, and other paleoclimate records from central and northeastern China, off the coast of northern Japan, southern Philippines, and Peru all demonstrate significant relationships [between solar activity and climate]. This suggests that solar activity drove Holocene variations in both East Asian Monsoon (EAM) and El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). In particular, the latter seems to have predominantly controlled the coastal climate of East Asia to the extent that the influence of precession was nearly muted during the late Holocene.”

Pendea et al., 2017 (Russia)“The Holocene Thermal Maximum (HTM) was a relatively warm period that is commonly associated with the orbitally forced Holocene maximum summer insolation (e.g., Berger, 1978; Bartlein et al., 2011). Its timing varies widely from region to region but is generally detected in paleorecords between 11 and 5 cal ka BP (e.g., Kaufman et al., 2004; Bartlein et al., 2011; Renssen et al., 2012). … In Kamchatka, the timing of the HTM varies. Dirksen et al. (2013) find warmer-than-present conditions between 9000 and 5000 cal yr BP in central Kamchatka and between 7000 and 5800 cal yr BP at coastal sites.”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0959683616683255 Stivrins et al., 2017 (Latvia)“Conclusion: Using a multi-proxy approach, we studied the dynamics of thermokarst characteristics in western Latvia, where thermokarst occurred exceptionally late at the Holocene Thermal Maximum. … [A] thermokarst active phase … began 8500 cal. yr BP and lasted at least until 7400 cal. yr BP. Given that thermokarst arise when the mean summer air temperature gradually increased ca. 2°C beyond the modern day temperature, we can argue that before that point, the local geomorphological conditions at the study site must have been exceptional to secure ice-block from the surficial landscape transformation and environmental processes.” Bañuls-Cardona et al., 2017 (Spain)“During the Middle Holocene we detect important climatic events. From 7000 to 6800 [years before present] (MIR 23 and MIR22), we register climatic characteristics that could be related to the end of the African Humid Period, namely an increase in temperatures and a progressive reduction in arboreal cover as a result of a decrease in precipitation. The temperatures exceeded current levels by 1°C, especially in MIR23, where the most highly represented taxon is a thermo-Mediterranean species, M. (T.) duodecimcostatus.”

- See more at: notrickszone.com

|

|