Climate change

Climate Consensus - the 97%

Global warming is increasing rainfall rates

A new study looks at the complex relationship between global warming and increased precipitation

Jared Bakko hauls a boat down a flooded road after taking supplies to his grandmother as the Red River flood waters began to recede just south of Moorhead, Minnesota, USA, 28 March, 2009. EPA/CRAIG LASSIG Photograph: Craig Lassig/EPA

John Abraham

Wednesday 22 March 2017 10.00 GMT

The world is warming because humans are emitting heat-trapping greenhouse gases. We know this for certain; the science on this question is settled. Humans emit greenhouse gases, those gases should warm the planet, and we know the planet is warming. All of those statements are settled science.

Okay so what? Well, we would like to know what the implications are. Should we do something about it or not? How should we respond? How fast will changes occur? What are the costs of action compared to inaction? These are all areas of active research.

Part of answering these questions requires knowing how weather will change as the Earth warms. One weather phenomenon that directly affects humans is the pattern, amount, and intensity of rainfall and the availability of water. Water is essential wherever humans live, for agriculture, drinking, industry, etc. Too little water and drought increases risk of wild fires and can debilitate societies. Too much water and flooding can occur, washing away infrastructure and lives.

It’s a well-known scientific principle that warmer air holds more water vapor. In fact, the amount of moisture that can be held in air grows very rapidly as temperatures increase. So, it’s expected that in general, air will get moister as the Earth warms – provided there is a moisture source. This may cause more intense rainfalls and snow events, which lead to increased risk of flooding.

But warmer air can also more quickly evaporate water from surfaces. This means that areas where it’s not precipitating dry out more quickly. In fact, it’s likely that some regions will experience both more drought and more flooding in the future (just not at the same time!). The dry spells are longer and with faster evaporation causing dryness in soils. But, when the rains fall, they come in heavy downpours potentially leading to more floods. The recent flooding in California – which followed a very intense and prolonged drought – provides a great example.

Okay so what have we observed? It turns out our expectations were correct. Observations reveal more intense rainfalls and flooding in some areas. But in other regions there’s more evaporation and drying with increased drought. Some areas experience both.

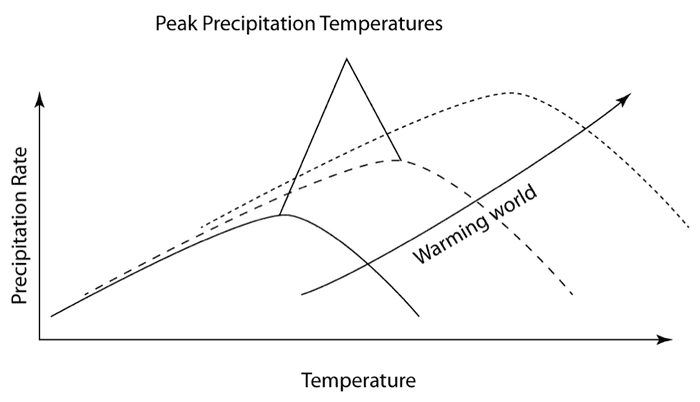

Some questions remain. When temperatures get too high, there’s no continued increase in intense rain events. In fact, heavy precipitation events decrease at the highest temperatures. There are some clear reasons for this but for brevity, regardless of where measurements are made on Earth, there appears to be an increase of precipitation with temperature up until a peak and thereafter, more warming coincides with decreased precipitation.

A new clever study by Dr. Guiling Wang from the University of Connecticut and her colleagues has looked into this and they’ve made a surprising discovery. Their work was just published in Nature Climate Change. They report that the peak temperature (the temperature where maximum precipitation occurs) is not fixed in space or time. It is increasing in a warming world.

The idea is shown in the sketch below. Details vary with location but, as the world warms, there is a shift from one curve to the next, from left to right. The result is a shift such that more intense precipitation occurs at higher temperatures in future, while the drop-off moves to even higher temperatures.

An idealized example of increasing precipitation curves as the world warms for the Midwest. Illustration: John Abraham

The authors also looked at how we characterize the temperature/precipitation relationship. Traditionally, we have related precipitation events to the local average temperature. However, it’s clear that there’s a strong relationship between the peak temperature and the precipitation rates. In fact, relations reveal that precipitation rates are increasing between 5 and 10% for every degree C increase. The expected rate of increase, just based on thermodynamics is 7%.

The authors find that in some parts of the globe, the relationship is even stronger. For instance, in the tropics, there’s more than a 10% increase in precipitation for a degree Celsius increase in temperature. This is not unexpected because precipitation releases latent heat, which can in turn invigorate storms.

From a practical standpoint, this helps us plan for climate change (it is already occurring) including planning resiliency. In the United States, there has been a marked increase in the most intense rainfall events across the country. This has resulted in more severe flooding throughout the country.

In my state, we have had four 1000-year floods since the year 2000! Two years ago, Minneapolis, Minnesota had such flooding that people were literally fishing in the streets as lakes and streams overflowed and fish escaped the banks. No joke, I actually observed fish swimming past me as I waded up a street. This occurrence is being observed elsewhere in my country and around the world.

It falls upon city planners and engineers to design infrastructure that is more able to accommodate heavy rains and manage water. This means designing river containment areas or flood plains, reinforcing buildings and houses, and increasing the capacity of storm drainage in urban areas, just to name a few. These modifications present costs but not preparing for increased flooding poses even greater financial and social costs. Moreover, storing water from times when there is too much for the inevitable times when we have too little (drought), results in better water management and multiple benefits.

This shows why climate science is so important. The US government is in the process of decimating our climate science infrastructure. The current US congress and our president have lost the battle of science – they have no reputable scientists to hide behind in their climate change denial. But, what they are doing instead is decapitating our ability to predict and plan for the future. By defunding organizations like NASA, the EPA, and NOAA, they are making us fly blind into a future.

For comparison, the proposed increase in the Department of Defense budget would enable our military to buy more expensive weapons like the US Navy Joint Strike Fighter. At approximately $335 million per plane, giving up just six of those planes would be enough to maintain the climate budget of NASA.

I worked on the Joint Strike Fighter as a consultant. I understand the need to have a national military. But giving up our understanding of a changing climate for six jet fighters is actually decreasing our security, is, in plain English, dumb. It seems that our elected officials have a strange values system – a values system that will end up presenting us with much higher social and economic costs.

I hope we remember these values next time we have fish swimming in our streets or droughts shriveling our crops.

theguardian.com |