There was a detailed write up in the financial media regarding the 3 men who create the content for Zero Hedge, one or two of them had worked on Wall street and also for a hedge fund.

The guys are US based from what I have read and they had a falling out and one of the 3 left.

I don't have the article handy.... it made the rounds in Bloomberg and on Reuters.....

interesting article on seeking alpha regarding the Zero Hedge gang.

seekingalpha.com

--------------------------------------------------------------------

The Ponzi Scheme Accusation

In the end, most of these hysteria-focused tough-guy financial bloggers lead to the same conclusion: the markets are a ponzi scheme being orchestrated by Central Banks.

This is the recent argument of Seeking Alpha writer The Heisenberg, who I would like to nominate as the funniest contributor to this website. We should remember that The Heisenberg is an anonymous blogger who uses the persona of a fictional high school chemistry teacher who manufactures methamphetamines.

The Heisenberg has frequently argued that you cannot understand financial markets if you do not understand geopolitics. While the presence of successful and mostly domestic-focused investors like Warren Buffet makes me question that assertion, The Heisenberg has stayed true to his ethos and made arguments focused on the big picture, instead of fundamental investing.

This makes The Heisenberg's articles fun reading, but his recent association of equities, Central Banks, and fraud is worth unpacking and understanding, because if not properly understood it can lead unsuspecting investors to lose out on potential gains from stock market investing.

In his recent piece titled, I'm the Idiot, this anonymous blogger notes that "Because none of the above changes the fact that this is a ponzi scheme." It's very unclear what "this" exactly is--I'm not sure whether he means the recent run up in U.S. stocks, the recent run up in global stocks, or stocks in general. Elsewhere in the same article, The Heisenberg makes the following assertion:

"Simply put, it isn't possible for financial assets to fall in the face of a liquidity tsunami of that size. Especially when the likes of the BoJ are timing their stock buying to coincide with market dips (and for the umpteenth time, that isn't speculation, it's explicit policy - just Google it).

So when I hear people say they 'don't believe that central banks are behind this,' it's difficult for me to know how to respond. How would you respond if someone told you that they 'don't believe out-of-control avocado buying relative to avocado supply is behind the rapid increase in avocado prices'?"

These paragraphs are almost clear, but not really. It seems the blogger is saying that financial asset prices are going up because Central Banks like the Bank of Japan are buying up those assets.

This sounds reasonable; it appeals to common sense while also sounding like the tough guy fighting the establishment by speaking Truth to Power. So it appeals to our emotions while sounding smart. And, as if taking a page from the Zerohedge School of Financial Journalism, The Heisenberg ends with a chart (itself from Mark Cudmore) showing equity valuations and central bank balance sheets seemingly going in lock-step from 2009 to the present.

There are many problems with this argument.

First, let's start with the chart. The chart compares the balance sheet of these central banks with the market cap of global equity markets in U.S. dollar terms, thus bringing with it the noise of foreign currency fluctuations. You may also be surprised to learn that the CAGR of the market cap in that chart is about 9%-well within the historic norm of common equity returns. Finally, you may also note that the market cap line shoots up from 2009 to 2011, while there's a slow growth in the balance sheet line (something similar happens in 2013-2015).

Then there's the premise of the argument. It makes sense to think that avocado prices are going up because there's "out-of-control avocado buying." And, if I understand The Heisenberg correctly, he seems to be saying this is what's happening to "financial assets".

But this isn't exactly what's happening.

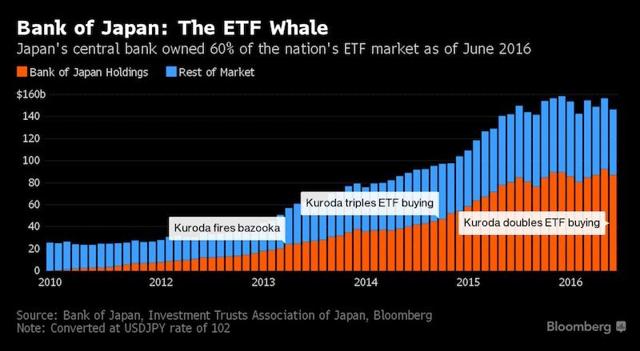

In Japan, admittedly, it is. The Bank of Japan has committed to purchasing a wide range of financial assets, including common stocks of Japanese companies. That is leading the BoJ to become the biggest stockholder in Japan.

Very interesting, but not terribly relevant for your retirement.

Why? Because this is only limited to Japan and is new enough to post-date the chart The Heisenberg borrows. As Bloomberg notes, this buying only started in 2011 and reached significance only in 2013 or so:

Other central banks, however, are NOT buying stocks or ETFs. The Federal Reserve limited its purchases to bonds, with U.S. Treasuries mostly being the target asset (although mortgage-backed securities were also important in 2013). You can read more about the differences between the Fed's and other QE programs here.

Now, if we apply The Heisenberg's argument to U.S. Treasuries, we would see U.S. Treasury prices explode due to the explosive demand for Treasuries from the Fed. To rephrase the blogger, "How would you respond if someone told you that they 'don't believe out-of-control U.S. Treasury buying relative to Treasury supply is behind the rapid increase in Treasury prices'?

So did U.S. Treasury prices explode during the QE years of 2009-2014?

No.

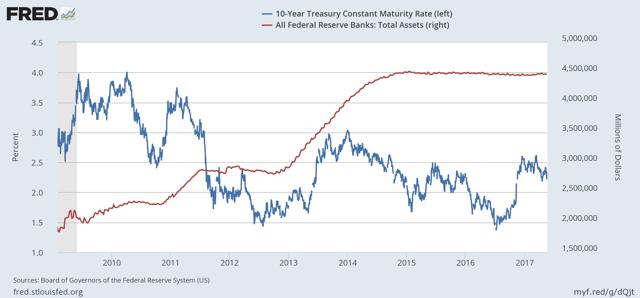

This is a chart of the maturity rate paid on 10-year U.S. Treasuries. Remember that interest rates and prices are inversely related on bonds, so when this line goes up the price goes down and vice versa. Here we see the line trending slightly lower, but the change is very slight.

In other words, prices aren't exploding despite aggressive Fed purchasing of these assets. Now if we compare this to Federal Reserve assets, we see the lack of a correlation even more clearly:

The red line has skyrocketed, but Treasury prices have gone up only slightly over the same time period.

This chart is telling you that out-of-control U.S. Treasury buying relative to Treasury supply is NOT behind the rapid increase in Treasury prices. In fact, if we zoom in on the period from late-2012 to the end of 2013, during the particularly aggressive asset-buying bonanza of QE3, we actually see U.S. Treasury prices going down while there is tremendous demand for Treasuries from the Federal Reserve at the same time.

How is this possible? It's almost as if the simple law of supply and demand doesn't apply to U.S. Treasuries. And, yes, that is exactly what you're seeing here. It would take several years of university-level financial and economic education to explain this, but I can at least say this:

U.S. Treasuries are not avocados.

What are Stocks?

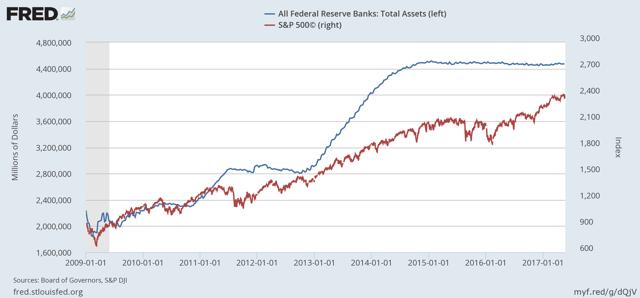

While the Fed hasn't purchased U.S. stocks, the argument I commonly come across from permabears is that QE distorted the market by causing funds to flow into equities that would've otherwise gone elsewhere. Thus while not buying stocks directly, the Fed effectively caused the stock market to go up. The chart invariably used to make this argument is one comparing the Fed's assets to the S&P 500:

Why, however, did the Fed's purchasing of Treasuries cause stock prices to go up but didn't cause Treasury prices to go up since the Fed only bought Treasuries and didn't buy stocks?

There are many very complicated and conspiratorial answers to this question, such as "the Fed is lying. They bought stocks in secret." One can't argue with this level of paranoia, so let's stick to the displaced asset theory.

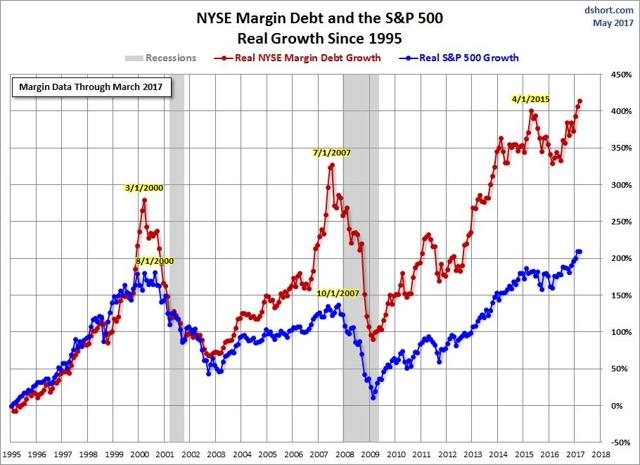

One big problem with the theory is that it relies on a mechanism by which U.S. dollars go from the Fed into the S&P 500-and that mechanism has never been discovered. There are plenty of possible explanations, but they remain unproven. One popular explanation is that cheap credit has caused margin balances to explode, thus resulting in over-levered bets on stocks; charts of high margin balances are often proffered to prove this point. And the numbers sound scary; margin debt was $536.93 billion at the end of March 2017 versus $173.3 billion in February 2009 (CAGR: 13.4%). However, the S&P 500's market cap has also gone up from $8 trillion to $20 trillion in the same time period (CAGR: 10.7%).

In other words, the rate of margin debt has increased slightly higher than the rate of stock price growth over the same period. That may be a cause for concern-or it may be the result of investors using margin on non-S&P 500 stocks and other assets.

In any case, there is little evidence that the growth in margin debt is the result of QE. In fact, we see margin debt growth in 2016 and 2017, long after QE is over and during the Fed's period of tightening monetary policy:

Source: Investing.com

Could it be that margin debt and S&P 500 market cap are both going up not because of the Fed but because a lot of investors think stocks are a better thing to buy now than they thought back in 2009?

To answer that question, let's take a big step back and remind ourselves of what stocks are and why people buy them.

Stocks represent fractional ownership in a corporation, which is a legal entity that uses a variety of managed assets to produce earnings. Thus at its core (although there are exceptions), investors buy stocks to get a piece of a company's earnings. Even exceptional stock purchases are indirectly connected to this ultimate goal: to get a piece of a firm's earnings.

Remember that owners get future earnings of a company, not past earnings. If a pizza shop earned $1 million in 2016 and I bought the shop on Jan 1, 2017, I get 0% of that $1 million but 100% of all earnings from the date that I bought the shop. Stocks work the same way.

Thus stocks are considered a forward-looking asset: people buy them not to get a piece of past earnings but a piece of future earnings.

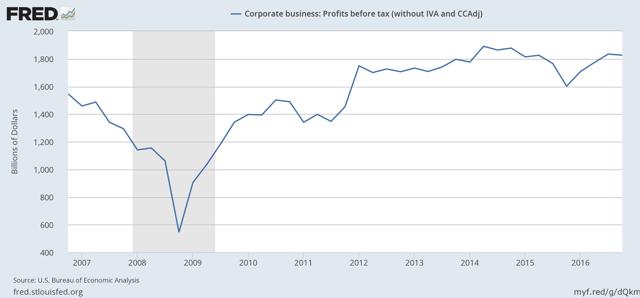

And that's the problem: no one knows future earnings. This is why stock bubbles and crashes happen; for moments, people incorrectly overestimate or underestimate how much firms will earn in the future. In 2009, they massively underestimated future profitability largely because they had seen a recent crash in profits (due to the housing crisis and Great Recession) and incorrectly extrapolated that this crash would continue:

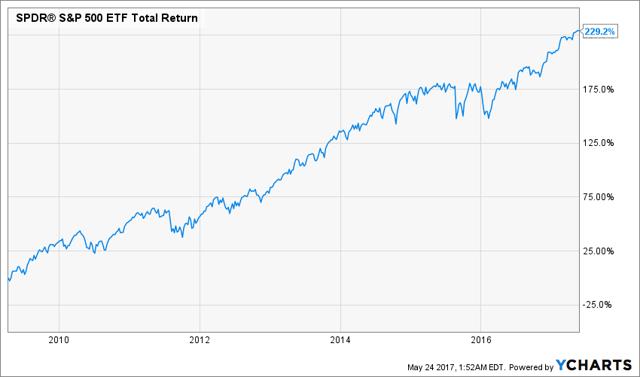

This is also when Zerohedge started blogging. It was a time of intense fear and anxiety; for many it literally felt like the world was ending. Zerohedge also posted confidently that "a date as early as next Monday could be a veritable D-day," citing a wise and anonymous "quant trader". That same trader also reportedly said "anyone who is doing anything sensible right now is either losing money or is out of the market entirely." Here's how an index fund has done since then:

For that quant's sake, hopefully his algorithms weren't designed to follow the advice he gave Tyler Durden.

However, this "end is nigh" rhetoric was hardly fringe back in 2009. Even in late 2009 the austere New Yorker wrote sympathetically about Zero Hedge's view "that pretty much everyone in power, in Washington and on Wall Street, is either incompetent or corrupt, and that our dissembling, bubble-abetting ways will lead to further doom." I saw friends and family members panic and restructure their lives; you probably know people who delayed retirement. The financial crash of 2009 was such a significant event that it made me change careers and go into finance, simply because I saw it as the m.... |