Fake news is an existential crisis for social media

Posted Feb 18, 2018 by Natasha Lomas ( @riptari)

Next StorySouth Korea aims for startup gold

Advertisement

The funny thing about fake news is how mind-numbingly boring it can be.

Not the fakes themselves — they’re constructed to be catnip clickbait to stoke the fires of rage of their intended targets. Be they gun owners. People of color. Racists. Republican voters. And so on. The really tedious stuff is all the also incomplete, equally self-serving pronouncements that surround ‘fake news’. Some very visibly, a lot less so.

Such as Russia painting the election interference narrative as a “fantasy” or a “fairytale” — even now, when presented with a 37-page indictment detailing what Kremlin agents got up to (including on US soil). Or Trump continuing to bluster that Russian-generated fake news is itself “fake news”.

And, indeed, the social media firms themselves, whose platforms have been the unwitting conduits for lots of this stuff, shaping the data they release about it — in what can look suspiciously like an attempt to downplay the significance and impact of malicious digital propaganda, because, well, that spin serves their interests.

The claim and counter claim that spread out around ‘fake news’ like an amorphous cloud of meta-fakery, as reams of additional ‘information’ — some of it equally polarizing but a lot of it more subtle in its attempts to mislead (e.g. the publicly unseen ‘on background’ info routinely sent to reporters to try to invisible shape coverage in a tech firm’s favor) — are applied in equal and opposite directions in the interests of obfuscation; using speech and/or misinformation as a form of censorship to fog the lens of public opinion.

This bottomless follow-up fodder generates yet more FUD in the fake news debate. Which is ironic, as well as boring, of course. But it’s also clearly deliberate.

As Zeynep Tufekci has eloquently argued: “The most effective forms of censorship today involve meddling with trust and attention, not muzzling speech itself.”

So we also get subjected to all this intentional padding, applied selectively, to defuse debate and derail clear lines of argument; to encourage confusion and apathy; to shift blame and buy time. Bored people are less likely to call their political representatives to complain.

Truly fake news is the inception layer cake that never stops being baked. Because pouring FUD onto an already polarized debate — and seeking to shift what are by nature shifty sands (after all information, misinformation and disinformation can be relative concepts, depending on your personal perspective/prejudices) — makes it hard for any outsider to nail this gelatinous fakery to the wall.

Why would social media platforms want to participate in this FUDing? Because it’s in their business interests not to be identified as the primary conduit for democracy damaging disinformation.

And because they’re terrified of being regulated on account of the content they serve. They absolutely do not want to be treated as the digital equivalents to traditional media outlets.

But the stakes are high indeed when democracy and the rule of law are on the line. And by failing to be pro-active about the existential threat posed by digitally accelerated disinformation, social media platforms have unwittingly made the case for external regulation of their global information-shaping and distribution platforms louder and more compelling than ever.

*

E

very gun outrage in America is now routinely followed by a flood of Russian-linked Twitter bot activity. Exacerbating social division is the name of this game. And it’s playing out all over social media continually, not just around elections. In the case of Russian digital meddling connected to the UK’s 2016 Brexit referendum, which we now know for sure existed — still without having all of the data we need to quantify the actual impact, the chairman of a UK parliamentary committee that’s running an enquiry into fake news has accused both Twitter and Facebook of essentially ignoring requests for data and help, and doing none of the work the committee asked of them.

Facebook has since said it will take a more thorough look through its archives. And Twitter has drip-fed some tidbits of additional infomation. But more than a year and a half after the vote itself, many, many questions remain.

And just this week another third party study suggested that the impact of Russian Brexit trolling was far larger than has been so far conceded by the two social media firms.

The PR company that carried out this research included in its report a long list of outstanding questions for Facebook and Twitter.

Here they are:

- How much did [Russian-backed media outlets] RT, Sputnik and Ruptly spend on advertising on your platforms in the six months before the referendum in 2016?

- How much have these media platforms spent to build their social followings?

- Sputnik has no active Facebook page, but has a significant number of Facebook shares for anti-EU content, does Sputnik have an active Facebook advertising account?

- Will Facebook and Twitter check the dissemination of content from these sites to check they are not using bots to push their content?

- Did either RT, Sputnik or Ruptly use ‘dark posts’ on either Facebook or Twitter to push their content during the EU referendum, or have they used ‘dark posts’ to build their extensive social media following?

- What processes do Facebook or Twitter have in place when accepting advertising from media outlets or state owned corporations from autocratic or authoritarian countries? Noting that Twitter no longer takes advertising from either RT or Sputnik.

- Did any representatives of Facebook or Twitter pro-actively engage with RT or Sputnik to sell inventory, products or services on the two platforms in the period before 23 June 2016?

We put these questions to Facebook and Twitter.

In response, a Twitter spokeswoman pointed us to some “key points” from a previous letter it sent to the DCMS committee (emphasis hers):

In response to the Commission’s request for information concerning Russian-funded campaign activity conducted during the regulated period for the June 2016 EU Referendum (15 April to 23 June 2016), Twitter reviewed referendum-related advertising on our platform during the relevant time period.

Among the accounts that we have previously identified as likely funded from Russian sources, we have thus far identified one account—@RT_com— which promoted referendum-related content during the regulated period. $1,031.99 was spent on six referendum-related ads during the regulated period.

With regard to future activity by Russian-funded accounts, on 26 October 2017, Twitter announced that it would no longer accept advertisements from RT and Sputnik and will donate the $1.9 million that RT had spent globally on advertising on Twitter to academic research into elections and civil engagement. That decision was based on a retrospective review that we initiated in the aftermath of the 2016 U.S. Presidential Elections and following the U.S. intelligence community’s conclusion that both RT and Sputnik have attempted to interfere with the election on behalf of the Russian government. Accordingly, @RT_com will not be eligible to use Twitter’s promoted products in the future.

The Twitter spokeswoman declined to provide any new on-the-record information in response to the specific questions.

A Facebook representative first asked to see the full study, which we sent, then failed to provide a response to the questions at all.

The PR firm behind the research, 89up, makes this particular study fairly easy for them to ignore. It’s a pro-Remain organization. The research was not undertaken by a group of impartial university academics. The study isn’t peer reviewed, and so on.

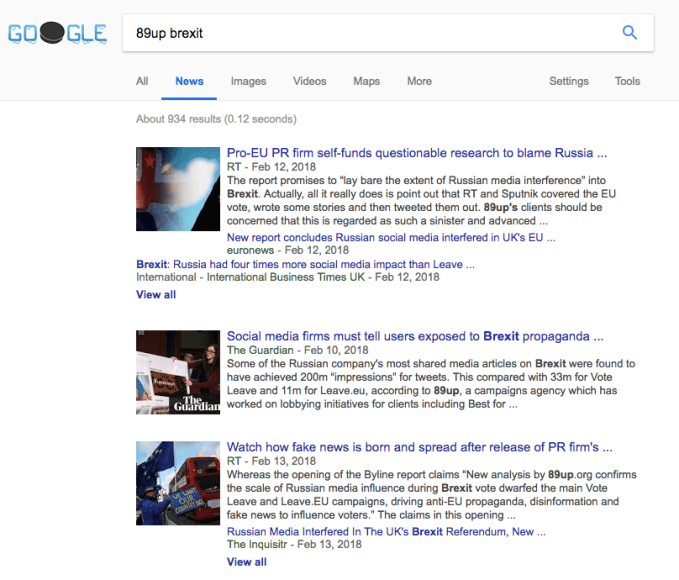

But, in an illustrative twist, if you Google “89up Brexit”, Google New injects fresh Kremlin-backed opinions into the search results it delivers — see the top and third result here…

Clearly, there’s no such thing as ‘bad propaganda’ if you’re a Kremlin disinformation node.

Even a study decrying Russian election meddling presents an opportunity for respinning and generating yet more FUD — in this instance by calling 89up biased because it supported the UK staying in the EU. Making it easy for Russian state organs to slur the research as worthless.

The social media firms aren’t making that point in public. They don’t have to. That argument is being made for them by an entity whose former brand name was literally ‘Russia Today’. Fake news thrives on shamelessness, clearly.

It also very clearly thrives in the limbo of fuzzy accountability where politicians and journalists essentially have to scream at social media firms until blue in the face to get even partial answers to perfectly reasonable questions.

Frankly, this situation is looking increasingly unsustainable.

Not least because governments are cottoning on — some are setting up departments to monitor malicious disinformation and even drafting anti-fake news election laws.

And while the social media firms have been a bit more alacritous to respond to domestic lawmakers’ requests for action and investigation into political disinformation, that just makes their wider inaction, when viable and reasonable concerns are brought to them by non-US politicians and other concerned individuals, all the more inexcusable.

The user-bases of Facebook, Twitter and YouTube are global. Their businesses generate revenue globally. And the societal impacts from maliciously minded content distributed on their platforms can be very keenly felt outside the US too.

But if tech giants have treated requests for information and help about political disinformation from the UK — a close US ally — so poorly, you can imagine how unresponsive and/or unreachable these companies are to further flung nations, with fewer or zero ties to the homeland.

Earlier this month, in what looked very much like an act of exasperation, the chair of the UK’s fake news enquiry, Damian Collins, flew his committee over the Atlantic to question Facebook, Twitter and Google policy staffers in an evidence session in Washington.

None of the companies sent their CEOs to face the committee’s questions. None provided a substantial amount of new information. The full impact of Russia’s meddling in the Brexit vote remains unquantified.

One problem is fake news. The other problem is the lack of incentive for social media companies to robustly investigate fake news.

*

T

he partial data about Russia’s Brexit dis-ops, which Facebook and Twitter have trickled out so far, like blood from the proverbial stone, is unhelpful exactly because it cannot clear the matter up either way. It just introduces more FUD, more fuzz, more opportunities for purveyors of fake news to churn out more maliciously minded content, as RT and Sputnik demonstrably have. In all probability, it also pours more fuel on Brexit-based societal division. The UK, like the US, has become a very visibly divided society since the narrow 52: 48 vote to leave the EU. What role did social media and Kremlin agents play in exacerbating those divisions? Without hard data it’s very difficult to say.

But, at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter whether 89up’s study is accurate or overblown; what really matters is no one except the Kremlin and the social media firms themselves are in a position to judge.

And no one in their right mind would now suggest we swallow Russia’s line that so called fake news is a fiction sicked up by over-imaginative Russophobes.

But social media firms also cannot be trusted to truth tell on this topic, because their business interests have demonstrably guided their actions towards equivocation and obfuscation.

Self interest also compellingly explains how poorly they have handled this problem to date; and why they continue — even now — to impede investigations by not disclosing enough data and/or failing to interrogate deeply enough their own systems when asked to respond to reasonable data requests.

A game of ‘uncertain claim vs self-interested counter claim’, as competing interests duke it out to try to land a knock-out blow in the game of ‘fake news and/or total fiction’, serves no useful purpose in a civilized society. It’s just more FUD for the fake news mill.

Especially as this stuff really isn’t rocket science. Human nature is human nature. And disinformation has been shown to have a more potent influencing impact than truthful information when the two are presented side by side. (As they frequently are by and on social media platforms.) So you could do robust math on fake news — if only you had access to the underlying data.

But only the social media platforms have that. And they’re not falling over themselves to share it. Instead, Twitter routinely rubbishes third party studies exactly because external researchers don’t have full visibility into how its systems shape and distribute content.

Yet external researchers don’t have that visibility because Twitter prevents them from seeing how it shapes tweet flow. Therein lies the rub.

Yes, some of the platforms in the disinformation firing line have taken some preventative actions since this issue blew up so spectacularly, back in 2016. Often by shifting the burden of identification to unpaid third parties (fact checkers).

Facebook has also built some anti-fake news tools to try to tweak what its algorithms favor, though nothing it’s done on that front to date looks very successfully (even as a more major change to its New Feed, to make it less of a news feed, has had a unilateral and damaging impact on the visibility of genuine news organizations’ content — so is arguably going to be unhelpful in reducing Facebook-fueled disinformation).

In another instance, Facebook’s mass closing of what it described as “fake accounts” ahead of, for example, the UK and French elections can also look problematic, in democratic terms, because we don’t fully know how it identified the particular “tens of thousands” of accounts to close. Nor what content they had been sharing prior to this. Nor why it hadn’t closed them before if they were indeed Kremlin disinformation-spreading bots.

More recently, Facebook has said it will implement a disclosure system for political ads, including posting a snail mail postcard to entities wishing to pay for political advertising on its platform — to try to verify they are indeed located in the territory they say they are.

Yet its own VP of ads has admitted that Russian efforts to spread propaganda are ongoing and persistent, and do not solely target elections or politicians…

|