LATE STAGE SOCIALISM: Hugo Chavez’s Failed Socialist Experiment Is Deadlier Than Ever.

I Lived in Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela. His Socialist Experiment Is Killing People

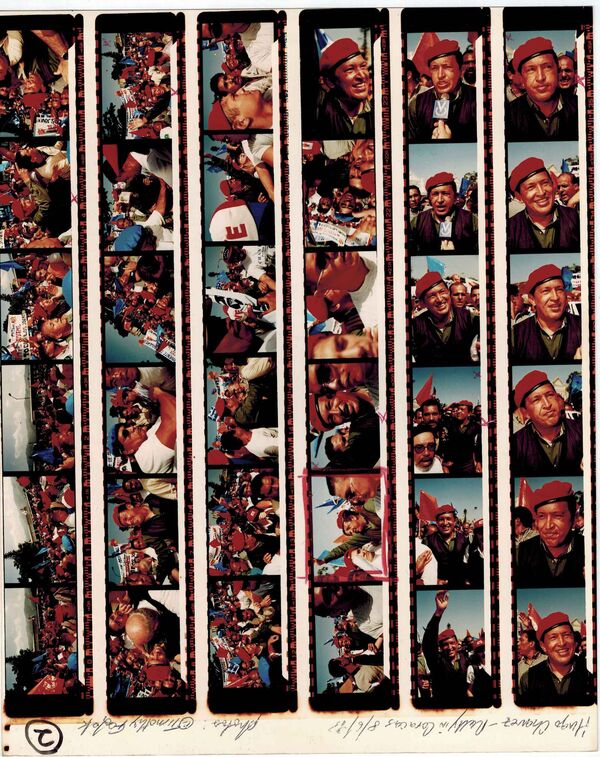

Chávez at a campaign rally in August 1998, months before his landslide victory. PHOTOGRAPHER: TIMOTHY FADEK Chávez at a campaign rally in August 1998, months before his landslide victory. PHOTOGRAPHER: TIMOTHY FADEK

Hugo Chávez had barely been in office two months when Nelson Chitty La Roche, a burly, gruff, gun-toting lawmaker from the Venezuelan political establishment, told me he was fed up. Chitty didn’t care for the way the young socialist leader was pushing around Congress and threatening to rule by decree, and he let out, somewhat flippantly, that he was starting to map out plans to have him impeached.

It was an absurd notion. In those heady, early days of the regime, Chávez was wildly popular. Polls showed he had the support of about 80 percent of the population, an estimate that, if anything, struck me as low. He was their showman, their savior, their avenger—the man who would speak for them and fight for them and provide for them.

Trying to drive him out of power then would have caused a wicked backlash. And yet here was a high-ranking lawmaker talking openly about such a possibility, giving voice to a notion I’ve heard countless times since—that the Chavistas’ days are numbered, that the regime is bound to collapse under the weight of its own incompetence.

Dec. 6 marks the 20th anniversary of the landslide electoral victory that first brought Chávez to power. And, amazingly, his socialist government still stands. (Nicolás Maduro took over as president upon Chávez’s death five years ago.) So when I hear chatter about the imminent demise of the regime, it leaves me somewhat cold.

Sure, the place seems ripe for change. Even from my vantage in the U.S., where the trauma of a kidnapping in Venezuela still haunts my family, the excruciating crisis the Chavistas have engendered is plain to see: the hyperinflation, the starvation, the epidemics. Talk of a military coup swirls constantly; international sanctions are hamstringing top officials; and neighboring governments, now in the hands of right-leaning leaders, are growing increasingly impatient with Maduro’s inability to control the flood of migrants pouring into their countries.

But this regime, through guile and brute force, has managed to overcome any number of existential challenges before. So while you should not be surprised to find the Chavistas out of power in, say, 20 days, you should equally not be surprised if they manage to survive for an additional 20 years.

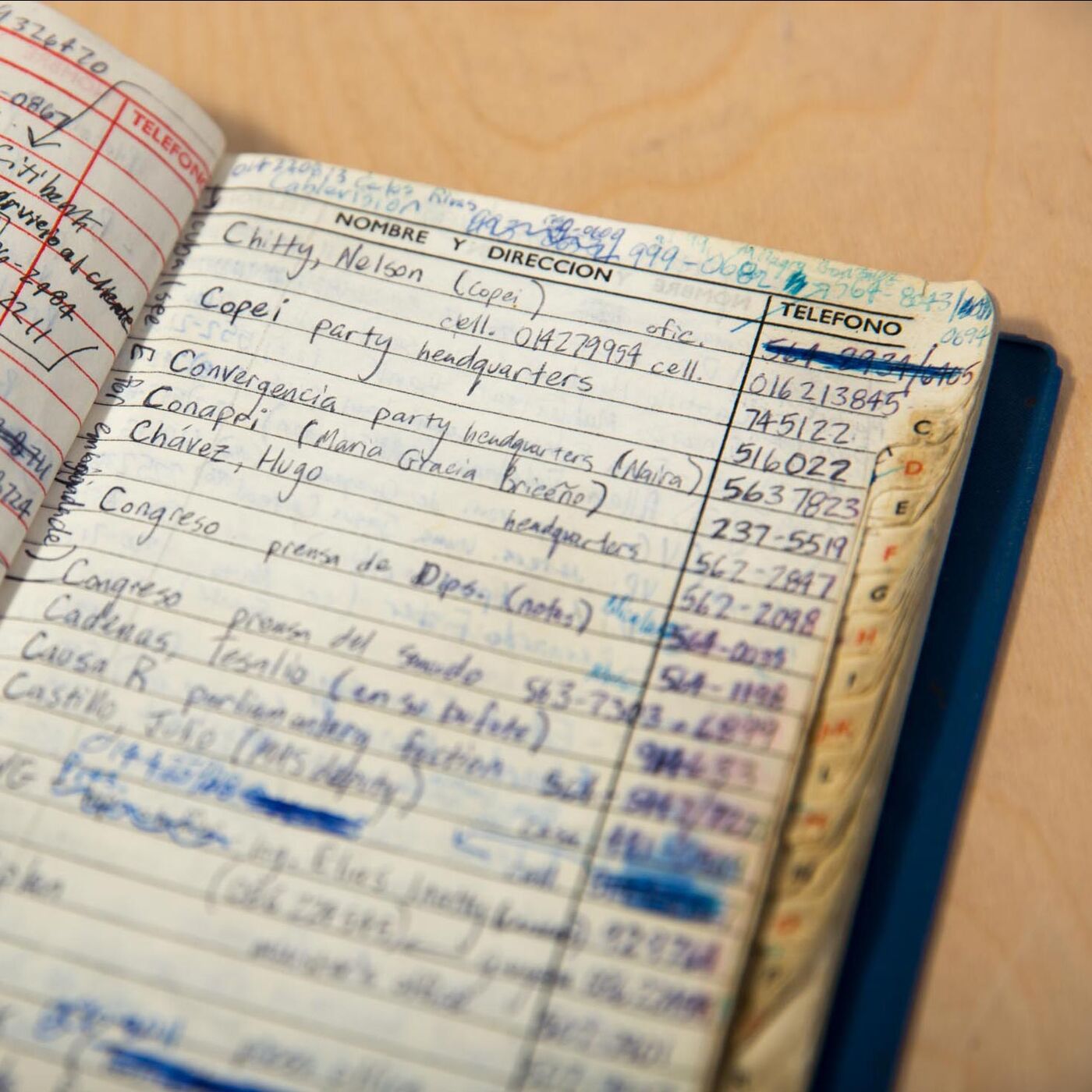

The phone book kept by the author in the 1990s.SOURCE: DAVID PAPADOPOULOSI arrived in Caracas in 1993. Just out of college, the trip was something of a lark—more an adventure than anything else. I stepped off the plane into what turned out to be the twilight years of Venezuela’s “Fourth Republic.” The go-go days of the 1970s oil boom—the AAA credit rating, the imported sports cars, the one-day shopping trips to Miami, where “We Accept Bolivars” signs hung in store windows—had long since passed. The hangover had set in. Venezuelans now refer to this period as the time “when we were happy and didn’t know it.” The phone book kept by the author in the 1990s.SOURCE: DAVID PAPADOPOULOSI arrived in Caracas in 1993. Just out of college, the trip was something of a lark—more an adventure than anything else. I stepped off the plane into what turned out to be the twilight years of Venezuela’s “Fourth Republic.” The go-go days of the 1970s oil boom—the AAA credit rating, the imported sports cars, the one-day shopping trips to Miami, where “We Accept Bolivars” signs hung in store windows—had long since passed. The hangover had set in. Venezuelans now refer to this period as the time “when we were happy and didn’t know it.”

A year before my arrival, Chávez, then a midlevel military officer, had orchestrated a coup attempt. He and his co-conspirators were sick of the corruption and inequality they saw. The coup was a bust—Chávez failed to take Caracas—but when the government agreed to let him address the country on national TV for a brief moment before surrendering, a cult figure was born: the silver-tongued rebel in the red beret.

When he launched his candidacy in 1998, following a presidential pardon, it became instantly clear there would be no stopping him. The country had been in economic decline for almost two decades, and, like the electorates across much of Europe and the Americas today, Venezuelans were desperate to hand the reins to an outsider. Watching the political establishment attempt to break his momentum was almost comical. They tried one trick after another, including forcing all but one of the main centrist candidates to back out of the race so they could put forward a single compromise nominee. It made no difference. Chávez won by almost 20 percentage points.

Contact sheet of photos from a Chávez rally on Aug. 6, 1998.PHOTOGRAPHER: TIMOTHY FADEK Contact sheet of photos from a Chávez rally on Aug. 6, 1998.PHOTOGRAPHER: TIMOTHY FADEK

The night of his victory, I remember leaving the Bloomberg News office in eastern Caracas, an upscale district that had to be one of the few spots in the country that hadn’t erupted in wild celebration. The streets were dead, the eerie silence interrupted only once by a handful of Chávez supporters on motorcycles making a rowdy foray into enemy territory to gloat.

Once in power, Chávez was nonstop action. He nationalized companies by the dozen, imposed controls on currency transactions, and set limits on the interest rates and prices businesses could charge. He purged the upper ranks of the state-run oil giant—the untouchable goose that laid the golden egg—and then had the company divert precious resources away from energy fields and into socialist-style manufacturing co-ops and other boondoggles.

He fended off a coup attempt, blacklisted voters who tried to have him recalled, took over the TV and radio airwaves, and created a Sunday talk show, Aló Presidente, where he waxed poetic about Simón Bolívar, mocked George W. Bush, and sang and told jokes for hours on end. He became the international darling of the leftist movement, shipping subsidized fuel to Nicaragua and Cuba (the Castros, in exchange, sent doctors and teachers to Venezuela), giving away heating oil to the poor in the Bronx, signing joint ventures with Iran and Russia, financing Argentina after its default, and even hobnobbing with Hollywood’s radical set—Sean Penn, Oliver Stone, Michael Moore. And, of course, he drafted a new constitution, giving birth to the “Fifth Republic,” which allowed him (and later Maduro) to seek reelection indefinitely.

I was long gone by the time most of this stuff happened. Passing up the chance to cover one of the most controversial figures of the 21st century may not have been the smartest decision of my journalistic career, but when Bloomberg offered me a posting in Brazil in 1999, I took it. I had seen Venezuelans suffer enough and had a strong premonition that things were about to get a lot worse. “Chávez is going to turn Venezuela into the next Cuba” was an expression you heard a lot in Caracas financial circles back then. It was a depressing thought—and ultimately a correct one. The wild oil rally of the 2000s, which took prices from $11 a barrel the day Chávez was elected to as high as $145, would delay the reckoning by about a decade. But it was inevitable.

So my Venezuelan girlfriend and I married and ran off to Brazil, where we spent a couple of years before eventually settling down outside New York City. We returned to visit her family every so often until 2008, when I walked out of the shower of our Connecticut home one morning to the sound of her frantic screams. I found her slumped on the dining room floor, the phone pressed to her ear, a wild look in her eyes. Her brother was calling from Caracas. Their father, he was telling her, had been kidnapped by Colombian guerrillas.

It’s the kind of call you always fear—there had been false alarms before, including a plot once to abduct the two of us—but never truly expect. The news struck her so violently that she fell ill. I rushed her to the hospital that afternoon, where they gave her some pills, and the next morning we were on a flight to Caracas with our two kids.

This sort of kidnapping had become common by then. It was easy to understand why. In Colombia, the right-wing president, Alvaro Uribe, was relentlessly hammering the guerrillas. Across the border in Venezuela, Chávez was projecting a much more accepting and forgiving stance toward his fellow leftists. So, naturally, they began moving deeper and deeper into Venezuela. The vast western plains became—and remain—lawless country: kidnapping, murder, land invasion, vigilante justice.

The guerrillas nabbed my father-in-law as he was arriving early one evening at his cattle ranch in San Carlos, a dusty little town several hours west of Caracas. Four of them hid in the brush by the front gate. When he pulled up, they pounced. Two guns—“big, scary guns, like Glocks,” he later told me—were pressed to his head. “ELN, kidnapping,” the men shouted. (Today, the ELN is Colombia’s biggest rebel group; reports suggest they continue to expand their operations in Venezuela, having recently pushed into the illegal gold trade.)

As they sped off into the surrounding hills, one of them told my father-in-law in a thick Colombian accent: “Jefe, we’ve been looking for you for many months.” They drove and walked for days, moving under the cover of darkness and feeding him canned sardines or the monkeys and opossums they killed.

Back in Caracas, we were kept on the move too. We’d been advised to frequently change locations because quick-strike second kidnappings weren’t uncommon. We slept little, trusted no one, and held late-night vigils. A week went by. Then another. And another. Finally, word came one evening there had been a breakthrough in ransom negotiations. He’d been freed at a junction not far from his ranch and was being rushed back to Caracas. It was a wild scene when he arrived that night. A kind of euphoria washed over everyone.

When my family and I boarded our flight back to New York a few days later, we left Venezuela for the last time. I’m sure we’ll return at some point, but truthfully the idea of going back—even for a few days—has almost never come up since. It’s all become too painful. Besides, who’s left? One brother moved to Panama shortly after the kidnapping. Then another one did. Finally the old man himself reluctantly made the move.

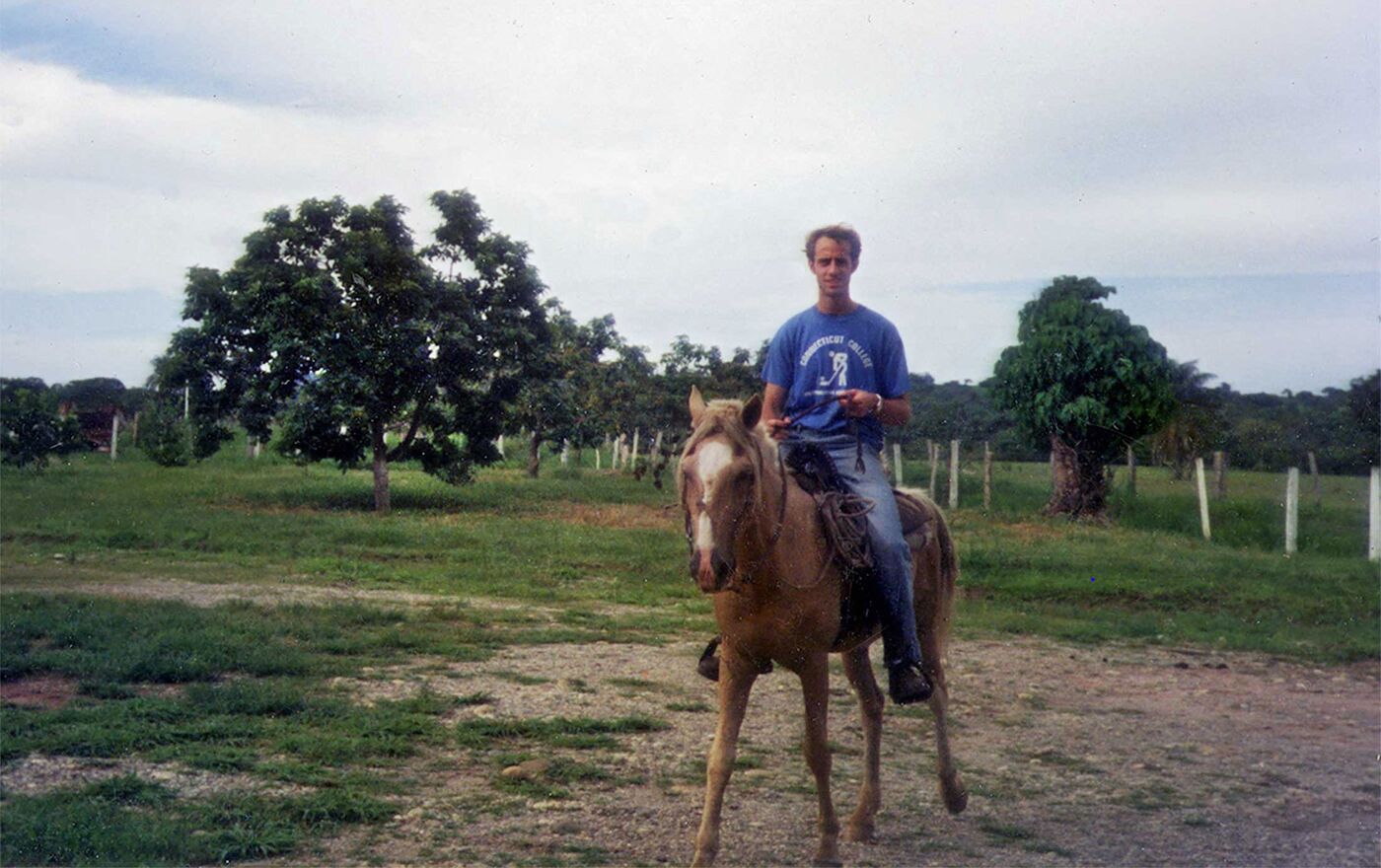

The author at his father-in-law’s ranch in San Carlos.SOURCE: DAVID PAPADOPOULOSIn so doing, they joined the early stages of the great Venezuelan exodus. Now, thousands leave every day. They can be found almost everywhere, including all around us in Norwalk, Conn. Within a few miles of our house, there are four Venezuelan restaurants. When we arrived here in 2001, we found only one—in the entire county. The author at his father-in-law’s ranch in San Carlos.SOURCE: DAVID PAPADOPOULOSIn so doing, they joined the early stages of the great Venezuelan exodus. Now, thousands leave every day. They can be found almost everywhere, including all around us in Norwalk, Conn. Within a few miles of our house, there are four Venezuelan restaurants. When we arrived here in 2001, we found only one—in the entire county.

Venezuelans, you see, were never migrants. Why would they be? The country is spectacularly beautiful and, as a founding member of OPEC, always took in enough petrodollars, even in the worst of times, to keep from sinking into the extreme despair that afflicted surrounding nations. But now, with the economy a fraction of its former size, oil production collapsing, the government’s bonds in default, inflation running above 200,000 percent, long-eradicated diseases reemerging, starvation killing off the weakest, the murder rate soaring, dissidents tortured, and votes rigged, there’s little, if any, reason to stay. Chávez and Maduro slowly, step by step, destroyed Venezuela’s economy and democracy. And the military, the one institution the two men always made sure to feed well, has remained—so far, at least—in the regime’s hip pocket.

There’s this fable about a frog and a pot of water that Venezuelans have adopted to describe what happened to them. Place a frog in a pot of boiling water, the story goes, and it will jump out. But place it in a pot of cold water and gradually, almost imperceptibly, ratchet up the temperature, and the frog will calmly sit there until it’s boiled to death.

The internet tells me this isn’t true, that the frog will jump out. But don’t mind that. It makes for a good fable and brings me back to Chitty and the conversation we had that day in 1999. Maybe I shouldn’t have scoffed at his impeachment idea. Maybe he was right. As improbable as it seemed, maybe the Chavistas needed to be removed right then and there, at the very first sight of unlawful conduct, long before they managed to bring the pot to a boil.

Before it's here, it's on the Bloomberg Terminal. LEARN MORE |