am guessing, but expect the direction correct, speed reasonable, acceleration soon

bloomberg.com

China's Next Moves Will Dictate Its Economic FutureDeng’s 1978 reforms gave China economic might. Now Xi wants more.

December 16, 2018, 7:00 AM GMT+8

Fred Hu will never forget the terror in his science teacher’s eyes when the man was dragged away to a Chinese jail during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution. Then a 12-year-old peeping into the classroom, his dream of escaping rural poverty to become a journalist or teacher seemed hopeless.

Two years later, his hope was rekindled when incoming leader Deng Xiaoping restarted university entrance examinations in late 1977, allowing all students to compete for a college place.

“For the first time there was a clear path in front of us,” said Hu, who went on to earn masters degrees at Tsinghua and Harvard, work for the International Monetary Fund, and lead Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in China. “The turmoil was behind us. A new era had come,” said the founder of Primavera Capital Ltd., a private-equity fund based in Beijing.

In the years that followed, Hu and hundreds of millions of others left the countryside and set up businesses in cities or went to work in factories that propelled China to become the world’s second-largest economy. Deng’s reforms, officially launched 40 years ago on Dec. 18 at a meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Committee, precipitated one of the greatest creations of wealth in history, lifting more than 700 million people out of poverty.

A small motor tricycle travels down a road near the township of Xintang in Hunan Province.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

But the changes also sowed the seeds of many of the problems China faces today. Two decades of growth at any cost under Presidents Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao starting in 1993 saddled the nation with polluted rivers and smoggy skies, plus a mountain of debt. During that time, China became deeply integrated into the global economy, a trend that accelerated after it joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

When President Xi Jinping assumed power in 2013, many hoped he’d turn out to be a leader in Deng’s reformist vein. But while Deng wanted his market-based reforms to make China rich, Xi has reasserted the control of the state in an effort to turn the country into a political and technological superpower.

“One of Xi’s overarching goals in terms of economic management is to effectively, if not formally, declare the end of the era of reform a la Deng Xiaoping,” said Arthur Kroeber, a founding partner and managing director at research firm Gavekal Dragonomics. Whereas Deng and subsequent leaders bolstered the role of private businesses in the economy and reduced that of the state, Xi seems to think the balance is now about right, Kroeber said.

Read more about the jaw-dropping industrial ambitions outlined in China’s Green Book

Deng Xiaoping in 1976.

Photographer: Bettmann Archives via Getty Images

Flouting Deng’s advice for China to lie low and bide its time, Xi went head to head with U.S. President Donald Trump and other world leaders, who were frustrated by years of Beijing stalling in opening its markets to foreign firms. China’s critics say domestic companies that are now aspiring for global dominance in technology and trade were raised on state subsidies or cheap loans while being protected from foreign competition.

The standoff has dealt Xi some of his first policy setbacks and an unusual upswing in public criticism in China. Even Deng’s son leveled a veiled rebuke in a speech in October, urging China's government to “keep a sober mind” and “know its place.”

The confrontation comes at a critical moment for China as it tries to avoid falling into what economists call the middle-income trap, where per-capita income stalls before a nation becomes rich. Usually that happens because rising wages and costs erode profitability at factories that make basic goods like clothes or furniture, and the economy fails to make the jump to higher-value industries and services.

Shift to Services

Contribution of major sectors to GDP

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Note: China's economy is roughly divided into the primary sector (agriculture), the secondary sector (construction, manufacturing), and the tertiary sector (services).

Only five industrial economies in East Asia have succeeded in escaping the trap since 1960, according to the World Bank. They are Japan, Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan.

To join them, Xi must oversee a transformation in China’s markets, injecting more competition in financial services, upgrading technology, and tightening corporate governance, while waging a trade war with a U.S. administration bent on containing the Asian nation’s rise. Xi’s challenge is compounded by an aging workforce, the mountain of corporate and local government debt, and an environmental clean-up that will take decades.

“No major economy that is not democratic has managed to surpass the middle income trap, so the odds are not in China’s favor even without the trade war,” said Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London. “Abandoning the Dengist approach has raised alarm bells in the West, particularly in the U.S. This makes the task much more difficult.”

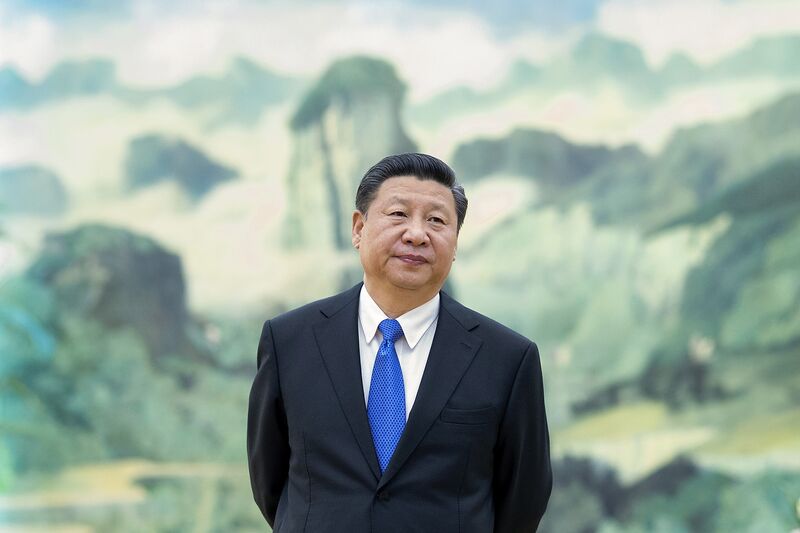

Xi Jinping

Photographer: Lintao Zhang/Getty Images

Whether China makes it will depend on the legacy of those migrants and entrepreneurs who took advantage of Deng’s opening and set up private companies and conquered one manufacturing industry after another. Today, China’s private sector generates 60 percent of the nation’s output, 70 percent of technological innovation and 90 percent of new jobs, according to Liu He, Xi’s top economic adviser.

Read more about Xi’s “unwavering” support for China’s private sector

Shadow BankingMany of those companies are feeling the brunt of Xi’s campaigns to deleverage the economy and battle pollution. A crackdown on shadow-bank financing has stifled a major source of funding during the boom years, while hundreds of thousands of small enterprises have been shuttered for despoiling the environment.

Their plight prompted an unprecedented push by policymakers this year to cajole banks into lending more to non-state companies, a campaign Xi endorsed by proclaiming his “unwavering” support for the private sector.

“There have been a lot of measures announced recently to restore confidence in the private sector, but it remains to be seen if they will work,” said Michelle Lam, a greater China economist at Societe Generale SA in Hong Kong. “To avoid a middle income trap, it’s really important to allow the private sector to play an even bigger role in the economy.”

The city of Shenzhen.

Photographer: Justin Chin/Bloomberg

Nowhere are the successes and challenges of China’s entrepreneurs more apparent than in Shenzhen, which over the course of the four decades evolved from fishing village to factory town to export hub and into the gleaming technology hub it is today.

Read more about how China flaunts the transformation story it wants you to see

Andy Yu, a native of Wuhan in central China, is typical of the people who made the immigrant city a success. He came to Shenzhen in 2003 to work at a technology company and set up his own mobile phone maker, Shenzhen Garlant Technology Development Co., a few years later.

“Some people say China can only make cheap junk but that’s not true,” Yu said. “China can make really good products and that’s why companies like Apple have factories here. China has the best price-to-quality ratio anywhere.”

Yu believes that combination of good quality at low prices will allow his company to shrug off Trump’s tariffs. About a fifth of Shenzhen Garlant’s $150 million in annual sales come from the U.S. and are subject to a 10 percent duty that could rise to 25 percent next year. Yu said he can pass on the increased cost to customers because his Western competitors sell at much higher prices while rival manufacturers in Southeast Asia and Latin America lag far behind in technology.

Trading Titan

Exports as % of world trade

Sources: International Monetary Fund, Bloomberg

Shenzhen Garlant’s trajectory shows how the beneficiaries of Deng’s reforms have had to adapt to survive. The company still designs and markets its products from Shenzhen, but its 300-worker factory is now in Hubei province in Central China where wages are lower. Yu is considering increasing automation and building a new plant in the west of the country on the border with Myanmar, which he could staff with migrant Burmese who earn half the amount that Chinese workers do.

To achieve Xi’s goal of dominating the key technologies, outlined in his “Made in China 2025” blueprint, the nation will need to do more than make high-spec phones and laptops. Yet Xi’s model of more government control coupled with tighter restrictions on lending could inhibit innovation.

“This year, the golden era for startups has ended,” said Wang Gaonan, one of the new generation of entrepreneurs who are driving change in China’s economy. “It’s almost impossible to find investors. The runway has vanished. If I had graduated in 2015 instead of 2012, it would be too late for me.”

Programmers working with motion capture equipment at Capstone Games headquarters in Beijing.

Photographer: Gilles Sabrie/Bloomberg

Wang, who holds a masters degree in industrial engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, heads Capstone Games, creator of the third- and fourth-ranked soccer games in Apple’s China app store. Founded in 2013, the Beijing company’s annual revenue has more than doubled every year to reach about 150 million yuan ($21.8 million).

Tighter controls on new game releases in China, where the government is concerned about the effects of device addiction on children, along with a slowing economy, have spurred Wang to look abroad for growth. Capstone plans to launch an app in the U.K. in March.

Tighter ControlXi has also clamped down on activities from online posts to the free-wheeling private businesses that grew up as a result of Deng’s policies, reasserting the control of the party on businesses and through regulations, state-run companies and government-owned banks. The economic impact of those controls shows up only after a time, so it’s hard to assess the effect now, said Nobel laureate economist Michael Spence, a professor at New York University’s Stern School of Business. “Taken too far that could create headwinds for innovation,” he said.

Overtaking Maneuver

Change in share of global GDP

Sources: The World Bank, Bloomberg

Yet even with the political and trade headwinds, the new digital economy, services and higher value producers could keep China on track to join the ranks of wealthy nations, said Spence. “A trade war expanding to technology and cross border investment will slow China down — and not just China — but not probably derail this progress,” he said.

The economy expanded 6.5 percent in the third quarter, the slowest pace since the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2009. But if China can keep the rate above 5 percent well into the 2020s, per capita income levels will close the gap on developed nations, said Kroeber, who is the author of “China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know.”

Still, average income levels only tell part of the story. Back in the small, rural town of Xintang in Hunan province, where Fred Hu saw his teacher arrested more than half a century ago, the inequality created by China’s boom is plain to see.

Miluo Xintang Middle School in Xintang.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

The paint on the walls of the Middle School Hu attended is peeling. Heating is minimal, which is why on a cold December day students sit at their desks wearing winter jackets. Education standards lag those in cities, said Senior Teacher Pan Yuezhong, 60. About 80 percent of students are “left-behind kids” — children whose parents left for higher-paying jobs, usually on the industrial east coast, and who are looked after by grandparents, relatives or friends.

“China has failed to invest in its single most important asset: its people,” said economist Scott Rozelle at Stanford University. “It has one of the lowest levels of education.”

Fred Hu

Photographer: David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

According to the country’s own 2015 microcensus, only 30 percent of the labor force has finished high school. That puts China behind all other middle-income countries, including Mexico, South Africa, Thailand and Turkey. While that has not deterred the country from becoming a manufacturing powerhouse, it will no doubt hinder its evolution into a more advanced, knowledge-based economy.

In China’s cities, colleges churned out more than 8 million graduates this year. But the problem lies in China’s neglected hinterlands, according to Rozelle. Rural workers are only one-fourth as likely as urban ones to have a high school education. But rural areas account for 64 percent of China’s overall population and more than two-thirds of its children.

Worse still, one in five people in Miluo, a county-level city that oversees Xintang, is over 60 years old, a demographic trend that pervades most of the country and one that will become an increasing burden on the economy in medical costs and care.

Aging Economy

Population according to age group

Source: United Nations

Still even in Xintang, things are better than in the dark days of the Cultural Revolution, when people used kerosene lamps for light, bound rags for shoes and rice was so precious it was often saved for the elderly, children or the sick, said Hu Fuxin, whose local dialect was translated by Pan, the teacher. Wearing a thick coat and a quilt over his legs to keep warm in the living room of his modest home, the 78-year-old former teacher remembered Fred Hu as a model student.

Large propaganda posters featuring former leader Deng Xiaoping and current Chinese president Xi Jinping stand on the side near Xintang.

Photographer: Qilai Shen/Bloomberg

Hu’s Primavera Capital invests in new economy companies such as online financial services platform Ant Financial Services Group and cloud service provider Xunlei Ltd. He said the creativity, innovation and vision of Chinese entrepreneurs is equal to those in Silicon Valley and other tech hubs and believes China can still ascend to developed-world status. Yet he’s become increasingly worried about the country’s policy direction under Xi.

“China’s on the right track, but everyone wants to know if they will speed up the reform process Deng initiated 40 years ago or will they slow down or backtrack,” he said. “A lack of reform may prevent China from fully realizing its economic potential.”

— With assistance by Kevin Dharmawan, Hannah Dormido, and Xiaoqing Pi

|